The author of Sorry to Disrupt the Peace reflects on writing out of desperation, Fiona Apple, and the novel as a ghostly space.

May 18, 2017

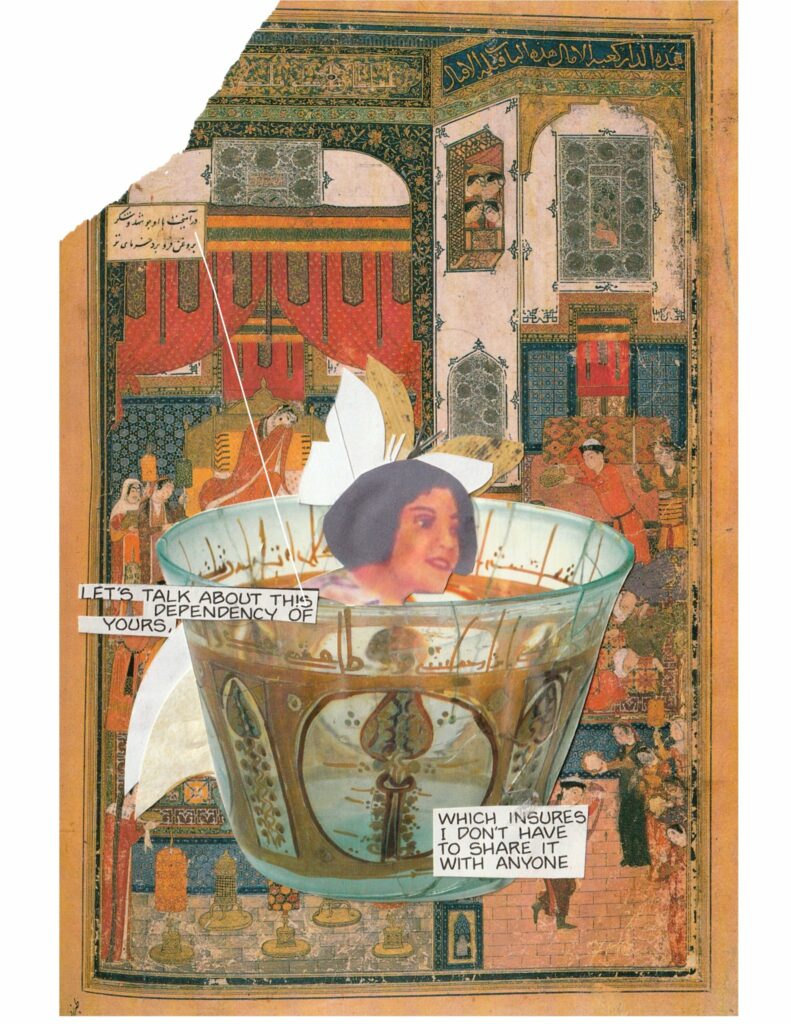

Multiple times throughout Patrick Cottrell’s debut novel, Sorry to Disrupt the Peace, Helen Moran, who returns home to her adoptive parents’ house to investigate her adoptive brother’s suicide, says, to no one, “Organize yourself!” Well, not no one. She is speaking to herself, but also to her family and to the house, which seems, in its inscrutable darkness and disarray, and also uncanny familiarity, to be withholding something essential. Helen’s mantra is as off-handed as it is heartbreaking; there is the feeling that the struggle to organize, out of the chaos of lives imperfectly lived and imperfectly shared, an understanding of the situation that influenced her adoptive brother’s suicide is fated to fail.

I doubt Helen would approve of this feeling. Her vision, I mean literally her act of seeing, is relentless. She sees everything! And you might think it is carrying her further away from what she is looking for. But, you know how sometimes when you are having a conversation with someone and you spend as much time looking all around and behind the person (at the wall, that poster, tree leaves, lights, other faces) as you do at their face? Then, recalling the conversation days or even year later, you picture not only the person’s face, but a fully realized environment, out of which the face reappears even more richly animated? In the same way, everything around Helen’s adoptive brother’s suicide is seen and felt. It is therefore imbued with the capacity to be a threshold, over which Helen, along with the reader, passes.

Patrick Cottrell is a writer of tremendous curiosity and compassion. His humor is organic and unsparingly honest. It deepens the gravity of the narrative that unfolds in Sorry. This narrative is also a narrative of LIFE; its humor and its absurdity are the pain of a LIFE expressed so specifically, so insightfully, and without a trace of embarrassment.

I have accompanied Patrick, via Helen (or maybe vice versa), through what is as exacting and imperative an odyssey as there is in contemporary writing. It is an odyssey to understand the recognizable and unrecognizable forms of grief emanating from the suicide of a sibling. It is also a journey to understand the conditions in which siblings live and grow apart, and the lives of Korean children adopted by white parents in America.

These are facets of an ongoing experience.

The following are a few short questions and answers, which Patrick and I shared by email.

Brandon Shimoda: I just finished reading your book for the second time, so I feel like I just got back from a long and unexpected trip home, or a translation of home, through which the original is still permeating. I wrote to you the first time that I was “completely unprepared for how overwhelming it all becomes.” Even though I was, the second time, re-entering the book, and therefore Helen’s mind, Helen’s adoptive parents’ house, etc., I felt the same way: unprepared for how overwhelming it all becomes. How has the experience been for you, of entering and re-entering the space and the life of this story, and especially the mind of Helen Moran, both while you were writing it and now?

Patrick Cottrell: I remember when you wrote to me about being unprepared for how overwhelming it becomes. I might have taken a picture of it on my phone. At the time, I hadn’t sent my manuscript to many people so I had no idea what the experience of reading it was like others. Entering the space of Helen’s mind was necessary for me. I had been reading a lot and not doing much writing. I like going long periods without writing because when I return to it, I feel desperate. I think writing out of desperation can be a good thing; it gives the work a sense of urgency.

The experience of writing Helen’s voice was kind of like the image of the waterfall. It was loud and overwhelming. And then it broke down and shifted into something else. Writing this book taught me how to pay attention to absurd details and the absurdity of the world. It was an uncomfortable book to write. I was obsessed, haunted, and probably not very fun to be around.

Looking back on it and re-entering the space of the book is bittersweet. It feels far away. My friend Leopoldine Core said that publishing her book and releasing it felt like a form of death. I think that’s right. It does feel like that. Then again, everything is always changing. I don’t think I’m the same person who began the book a few years ago. So maybe that’s a form of death, too.

Everything is always changing: you’re making me think of insects, and how some forms of transition or transformation very closely resemble death. Do you think books are like cocoons? By which I mean to ask—without turning this into too much of an exposé on your interior life: Who were you when you began the book? And, who are you now? And also, how, or by what, were you haunted?

When I began the book, I was in my early thirties. I used to walk three miles a day. It’s difficult to say who I was exactly, but I know whoever the person was, I’m not that person anymore. For a long time I kept a diary. I would write about the NBA and my favorite players. “It seems like Russell Westbrook has OCD.” I don’t do that anymore. I’m no longer interested in what goes on in my brain. I’m also a fairly private person. I can work around both of those things, the lack of interest in what goes on in my brain and the desire for privacy, through writing fiction. I was talking with someone on the phone the other day, and he was asking me questions which were intelligent and insightful, but I kept laughing and saying, “I don’t know.” I think that’s right.

The older I become, the more haunted I feel. I don’t mind it. It’s fine. I think it goes hand in hand with obsession. One thing that hasn’t changed at all is that I’ve always had an obsessive mind. Obsession can be useful for writing, even though it’s not as useful for life. I guess I could say that I wrote my book to try to impress three people. Two of the people are dead, and the third person is Fiona Apple.

Have you sent your book to Fiona Apple? Why did/do you want to impress her? I think, by the way, she would be impressed, at least, though also intrigued, empathetic, in love…

I haven’t sent my book to Fiona Apple. She seems like she’d be hard to reach. As I was writing my book I had this thought that she would be an ideal reader. An empathetic one. Kind. Slightly intimidating. It’s good to keep people who intimidate and scare you in the back of your mind as you write. A long time ago, a friend and I followed Fiona Apple around on her tour for When the Pawn…We gave her stuffed animals and she put them on her piano.

You could send her your book with a note that says: “Here is my latest stuffed animal…”

Speaking of stuffed animals—one of the most terrifying presences in the book (for me) is the European man. He appears for the first time early on in the book. Helen describes her parents’ grief over her brother’s suicide as “the fourth, yet-unspoken presence,” and gives it a “bodily form”: “a European man in his forties, average build and height, balding, with a red nose.” It’s a terrifying embodiment of grief, because it, or he, is so banal—he drinks coffee, eats pizza—but is especially so white. It’s like Helen sees her white adoptive parents replicating their whiteness through their grief. Who or what is the European man? How is the European man related to Helen’s experience as a Korean adoptee, as the adopted child of a white woman and man who Helen refers to as “ghost-figures”?

Everything in the book could be considered a ghost: the furniture, the house, the suburban street, etc. I don’t think the balding European man is that scary. He’s a figure from the past who comes to haunt the family in a banal way. His presence is an accumulation of all of Helen’s suburban experiences, which are steeped in European and American culture. He could be the embodiment of classical music or pizza with a side of ranch dressing or acting in a school play. His appearance coincides with Helen becoming unhinged as she starts to acclimate to the house, a space of passivity and avoidance, where there’s little movement. I write from an intuitive place. It seemed natural for a balding European ghost-figure to appear.

It’s a beautiful, also heartbreaking, conception—the book as a space in which ghosts and ghost-figures can be arranged and confronted, where we can be unsettled by what we are supposed to know and love. You said: “The older I become, the more haunted I feel.” As Helen starts to acclimate to the house, does she too become a ghost? Another way of asking is: how far can you (Patrick), I (Brandon) (we, any of us) go into our families and into our families’ spaces without becoming a ghost—to our families, to ourselves?

I don’t think Helen is a ghost. She retches too much to be a ghost.

I’m curious, could you say something more about what you mean by how far can we go into our families or into their spaces?

Yeah. I think of Helen “acclimating,” as you say, to her parents’ house, which is both furnished and populated by ghosts and ghost-figures, with the risk being that the more she acclimates, the more she becomes a ghost herself. But, then I think of my own experience returning home, and how every time I do, I become not only less recognizable to myself, but more illegible to my family. Like: family, and family spaces, are supposed to clarify who we are and how we have come to be, but for me, the opposite is more often true. I feel more obscure, more alienated, therefore more ghostly, even as I know and feel love. What is the experience, for you, of going home and visiting your family? Is it similar to Helen’s (ghosts and ghost-figures)?

The idea that family spaces should clarify who we are is rather horrifying. Personally, I don’t feel like a ghost when I go home to my parents’ house. I recognize myself, which is a comfortable and slightly repulsive feeling. It’s very safe and secure. I’ve never felt like a ghost with them, but I understand that other people might feel that way when they go home and see their families.

I would feel like a ghost if I returned to South Korea, which I hope to do one day. That’s where I was born. When I meet my biological parents and sisters, I think I will become unrecognizable to myself, because I’ve been absent from their lives for 35 years, and we know nothing about one another. I have no idea if we would like one another. So there’s a void there, and a lack of clarification. There’s nothing more ghostly than that absence.

Thinking of that absence, and returning to South Korea, I want to ask about the document Helen discovers on her brother’s computer: “A Note About Swans and Organs.” (I gasped, like I had fallen, when Helen opened the document; and I love how it’s reproduced in the book, inset, in gray.) In it, Helen’s brother describes his return to South Korea to meet his biological mother. Given that you haven’t returned to South Korea, what was the experience like for you to imagine and write this return? Have you imagined what it would be like to visit your biological parents and sisters in South Korea?

I don’t want to say too much about how anyone should read that document. But the Korea that appears in the book is the Korea of my imagination. It’s a real place and it isn’t. Writing that section was emotional for me. I used to have this worry that the note obliterates everything that comes before it and after it. Now I don’t care so much. I’ve come to peace with it.

My biological parents are divorced. My mother used to live on a farm, and everyone said she was happy there. Now she’s at a Buddhist monastery with one woman and one man. I’m curious about that arrangement. My father lives in the suburbs. I’ve heard that he’s harsh and controlling, whereas my mother is this innocent woman who has been swindled by various thieves throughout her life. I’ve imagined going on a picnic with my family. We’re sitting on a blanket underneath white umbrellas. That’s all I’ve pictured so far. I haven’t gone any further than that.