On the past and present of finding and sharing Asian diasporic literature

December 21, 2021

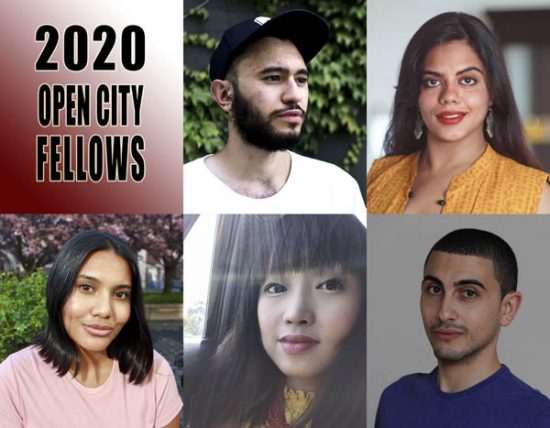

Editor’s Note: As the Asian American Writers’ Workshop celebrates its 30th anniversary, we invited current and former editors, writers, booksellers, community members, and workers to make new meaning from the Workshop’s archive. Together, they have awakened AAWW’s print anthologies and journals, returned to the physical spaces of the Workshop starting from our basement location on St. Mark’s, and given shape to the stories from within AAWW that circulate like rumors, drawing writers back again and again. In revisiting the Workshop’s history, we hope for insight into the ever-changing landscape of Asian diasporic literature and politics and inspiration to guide us forward in our next 30 years. Read more in our AAWW at 30 notebook here.

This December marks the opening of New York City’s only independent bookstore owned and operated by an Asian American woman. Yu and Me Books is located in Manhattan’s Chinatown, and its opening recalls the early history of the first Asian American bookstore on the East Coast, housed in the basement space of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop—cofounded by Curtis Chin, Christina Chiu, Marie Myung-Ok Lee, and Bino A. Realuyo—on 37 St. Mark’s Place.

From 1995 to 2000, during the time that AAWW’s bookstore was operating in that early location, a vertical red vinyl sign reading “Asian American Bookseller” would greet pedestrians strolling past. Upon relocating offices in 2000, the bookstore (and AAWW) shifted to the 10th floor of a building on 32nd Street in Manhattan’s Koreatown, and fewer people came wandering in off the street. Met with the competition of online retailers like Amazon in the early ’00s, the Workshop struggled to keep the store running. When the bookstore closed, it was reshaped into a vibrant reading room, which now lines the walls of AAWW’s current space in Chelsea.

To help connect the legacy of the East Coast’s first Asian American bookstore to the experiences of independent booksellers today, we asked four former Workshop staff who tended to AAWW’s bookstore and four Asian American booksellers today to send us postcard-sized snapshots of what it has meant to find and share a growing body of Asian diasporic literature. We’ve woven their micro essays to move forward and backward in time. What emerges is a profound love for the way books can forge new relationships, to other readers, to physical spaces, and also to one’s past.

Parag Rajendra Khandhar, Program Director, AAWW (1995-1997)

37 St. Mark’s Place, New York, NY

The first time I walked into the Asian American Writers’ Workshop was days after I graduated from university, upstate. I moved down to New York City to live on my friend’s couch in Stuyvesant Town, blocks from AAWW, the only Asian American organization that accepted my offer of free labor. I found the narrow doorway on St. Marks Place and walked down the semi-spiral of steps, unsure of what I was getting myself into. Once I opened the door, it was like a Hobbit hole, except I entered through a tiny bookstore, shelves laden with treasures I would discover and grow to cherish more than anything I might find in a larder or vault. Five yards ahead, the space opened up, there was a futon and coffee table, where AAWW cofounder Curtis Chin and others were holding court (or likely having lunch) in this unexpected subaltern setting.

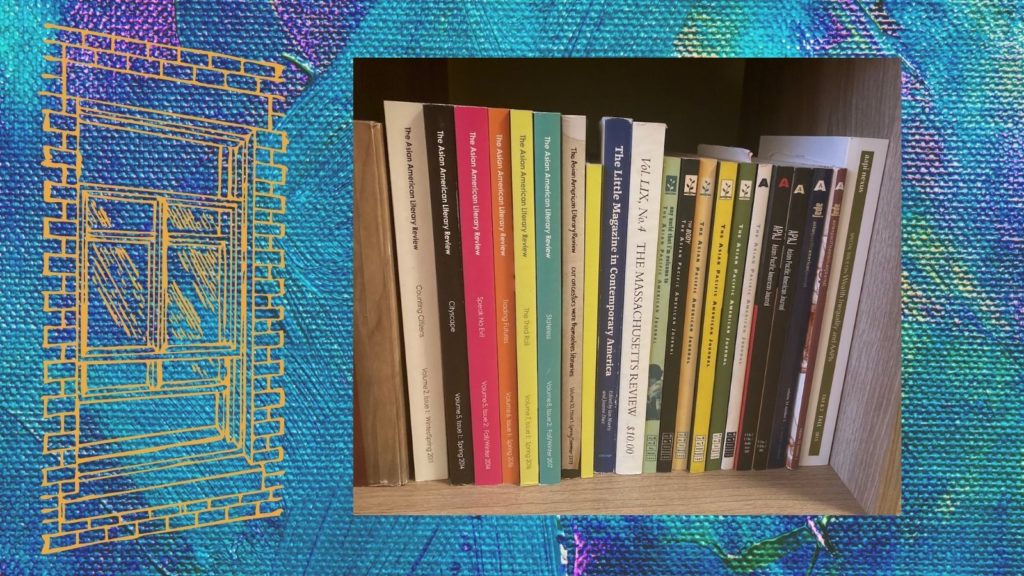

My initial charge was to manage the bookstore, and I did so with aplomb, building the collection, connecting with local Asian American studies classes, and even getting us written up in Newsday about the importance of a physical home for our collective written word. Curtis was proudest of the Bookseller’s Asian American poetry collection, sharing that it was hard for our poets to get shelf space in mainstream bookstores. I inherited that zeal and applied it to the collection of zines and CDs I pulled in on consignment from community artists, and hard to find monographs from community scholars across our imagined archipelago on Turtle Island.

I loved greeting new visitors and regulars with a “welcome home” vibe and saw them take in the tiny 10″ x 10″ space that we said was the greatest collection of Asian American books in one place on the East Coast. I enjoyed recommending books to people, lovingly pulling them off the shelves and placing them in their hands. I loved talking story about authors and their work, words and imagination, our histories and possible futures.

Welcoming people into the physical space that represented something much larger was my favorite thing of all… and I felt that most poignantly during AAWW readings and performances. When we expected a full house, we would move the large display cases that Curtis had procured from a museum to the side and pulled out as many seats as we could fit. I think we got 100 people into that space for Peeling the Banana performances. So much love in such a compact space and time. The Bookseller and AAWW space eventually became a cultural hub where community groups met, held fundraisers and performances, and we weaved a sense of aligned movement that still buoys my heart to this day.

Bonnie Chau, Bookseller, BookCourt (2011-2016) & McNally Jackson (2018-2020)

163 Court St and 76 N. 4th Street, Brooklyn, NY

I doubt anybody on this planet would describe me as a power-hungry person, but working in bookstores, I did feel excited by my powers. I could tell people what I thought they should read!

I worked part-time in independent bookstores in Brooklyn for eight out of the nine years that I lived in NYC: at BookCourt in Cobble Hill from 2011–2016, and then at McNally Jackson in Williamsburg from 2018–2020. At the same time that I moved to NYC and started working in bookstores, I was also starting to read more Asian/Asian diasporic writers, and this definitely meant that many of the books I was recommending were written by Asian/Asian diasporic authors. I loved walking through the store organizing books, rearranging them so that I could face-out certain ones I wanted to draw more attention to; I loved handselling books and compiling my staff picks—I remember one of my first picks at BookCourt was Sleepwalk by Adrian Tomine. I recommended Anelise Chen’s So Many Olympic Exertions to so many people. I actually met Anelise in 2012 in an AAWW workshop taught by Ed Lin; she was an Open City fellow at the time. I hadn’t really known about AAWW, but a coworker of mine at BookCourt had just started a job there and had encouraged me to take the class.

A lot of the new books by Asian diasporic writers I regularly recommended to customers were ones I just happened to come across through an advance reader copy: Bright Lines by Tanaïs, A Separation by Katie Kitamura, Ponti by Sharlene Teo, Things to Make or Break by May-Lan Tan, Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu; and a ton of books by Asian authors in translation as well. Working in a bookstore, I had access to a steady stream of ARCs of forthcoming titles. There’s something uniquely exciting—a real sense of discovery—when reading an amazing book in its galley form because they were books I hadn’t heard a single thing about because they hadn’t yet been reviewed in the media.

As a part-time bookseller I didn’t generally get first pick of the galleys, but somehow—perhaps not unrelated to the fact that I was usually one of the only Asian booksellers (if not the only one)—a lot of the titles by Asian/Asian diasporic authors would still be available on the galley shelves for me to snatch up. That’s also how I first came across The Vegetarian by Han Kang (tr. Deborah Smith), Severance by Ling Ma, White Tears by Hari Kunzru. I read those books maybe half a year before they were published—I remember this particularly about reading Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings—and inevitably there would be this moment where I’d be alone on some subway train late at night after a closing shift and I’d read the last page or arrive at my stop and have to shut the book and would look up feeling kind of dazed, kind of wild because there was nobody else around at that moment to whom I could be like, “oh my god have you read this you have to buy this and read it right now!!” But that was the thing, that was the power and privilege of being a bookseller. Once you stepped foot into the bookstore, you could do that, you were being paid to do that, that was precisely what you were meant to do.

Nancy Yap, Bookstore Manager, AAWW (1996-2001)

37 St. Mark’s Place, Manhattan + 16 West 32nd Street, New York, NY

Every time a new customer walked through the door of AAWW’s space on St. Mark’s Place, I asked them what brought them to the bookstore. Were they from out of town? Were they a student buying textbooks? Did they just accidentally find themselves here?

I was in my early 20s when I worked at AAWW. With indie rock shows and the ghost of Jimi Hendrix as our neighbors, the Workshop seemed perfectly placed. I loved the street we were on, I loved the basement, and I loved being surrounded with a diverse set of stories that my younger Ohio self could only dream of.

We were a bookstore that carried classics like No-No Boy by John Okada or Strangers from a Different Shore by Ron Takaki. Zines by Bamboo Girl or CDs by Mountain Brothers.

We sold work created by the first artists I managed: Beau Sia, Suheir Hammad, Alexander Chee, the Visionaries and of course, the feedBACK poets—Malaya Arevalo, Chia-Ti Chiu, Taiyo Takeda Ebato, Julie Hyun Jung Hwang, Kai Ma, Ishle Yi Park, F. Omar Telan, Masaki Yamagata, Helen Yum.

Even with so many titles in the store, I still craved more. I would hunt for stories of Asian Americans, from zines to major publications. I wanted to find them all, collect them all, support all the artists willing to tell our stories. The collection grew, and in our pre-Amazon world we were able to build a destination bookstore.

And… every day, Jeannie Wong would ask me if I had found my new best friend.

She knew that I loved hearing stories from customers about the stories they loved. She would watch me grow enamored with every new person who walked through the door.

I was often defensive about my new-found friendships. But, the truth was, she was right—I did meet a new best friend every day.

With the passing of a few new best friends from this era, Anantha Sudhakar and Richard Wright, I have been missing my AAWW family. Thank you to everyone who stopped by on my watch at the AAWW Bookstore. And thank you to the artists and stories that connected us.

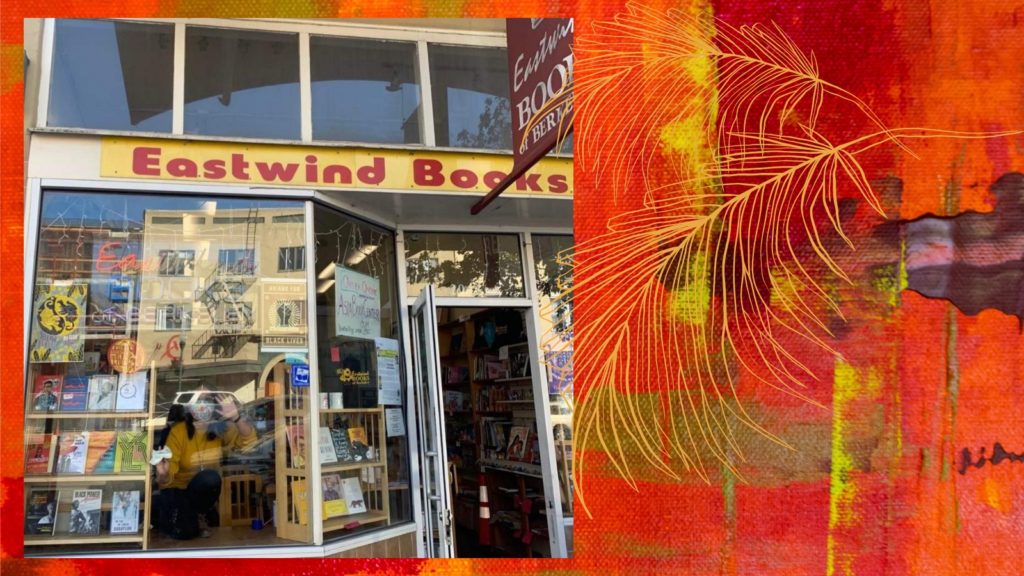

erika pallasigue, Operations Manager, Eastwind Books of Berkeley (2014-present)

2066 University Ave, Berkeley, CA

You walk into your local bookstore, scanning shelves, waiting for a spine, a title, a cover to catch your eye. Maybe you know which book you want. Maybe you’re searching for something to give to a loved one. Or maybe you’re just looking.

What is it you’re looking for?

As a bookseller, I’m an encouraging matchmaker.

You might like this one.

Choosing a book can be a deeply personal experience. The books that line my shelves at home are a reflection of who I am and where I’ve been. I know I’m not the only one for whom this rings true. As I scan barcodes and swipe credit cards, I can’t help but glance at the titles the reader has chosen. What do people like to read? As a bookseller, this is a vital question. The answers stock the shelves.

At Eastwind Books of Berkeley, we draw attention to books by Asian diasporic writers. As a community-based bookstore, we curate our collection to fit the needs of the communities we serve. And to do that, we have to listen.

Sometimes a reader will tell me how they’ve connected with a book as though the story becomes their own through shared history and struggle. I listen to the young person discovering a shared identity with a writer. I listen to parents encouraging their children to celebrate their heritage. I listen to elders bearing witness to the past, their stories finally written on the page, a gift for future generations. And I listen to people who simply don’t know where to start. What do you recommend?

As I place a book into an eager reader’s hands, I’m hopeful that they find meaning in the pages before them. It’s in these moments that I feel most proud of the work that I’ve chosen to do. I’ve learned that it takes more than just rattling off titles from a best-sellers list; it takes caring about a stranger’s perspective and wanting them to find what they need on their journey. For all the readers out there: keep reading—there are always more stories.

Pimpila Howe, Bookstore Manager, AAWW (2001-2003)

16 West 32nd Street, New York, NY

When I joined the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in the early ’00s, we were on the 10th floor of an office building in Koreatown. Not exactly an ideal spot for a bookstore. We had no regular foot traffic apart from people who came to the Workshop for events. Dedicated customers did seek us out, though. Professors directed their students to us for their course readings, and every fall and spring our shelves were stacked with classics like No-No Boy (John Okada), America is in the Heart (Carlos Bulosan), The Half-Inch Himalayas (Agha Shahid Ali), Woman Warrior (Maxine Hong Kingston), and Dictee (Theresa Hak Kyung Cha).

Sometimes we took our books on the road. Our biggest sale of the year always happened in May at the AAPI Heritage Festival in Union Square. We also set up booths at the annual conferences for the Association for Asian American Studies (AAAS) and Asian American Librarians. One year, when the AAAS conference was in Salt Lake City, we hung out with Steven Doi, a bookseller from San Jose specializing in rare Asian American titles. He drove us all around town in his van. I remember thinking, this was what community felt like, across so many miles.

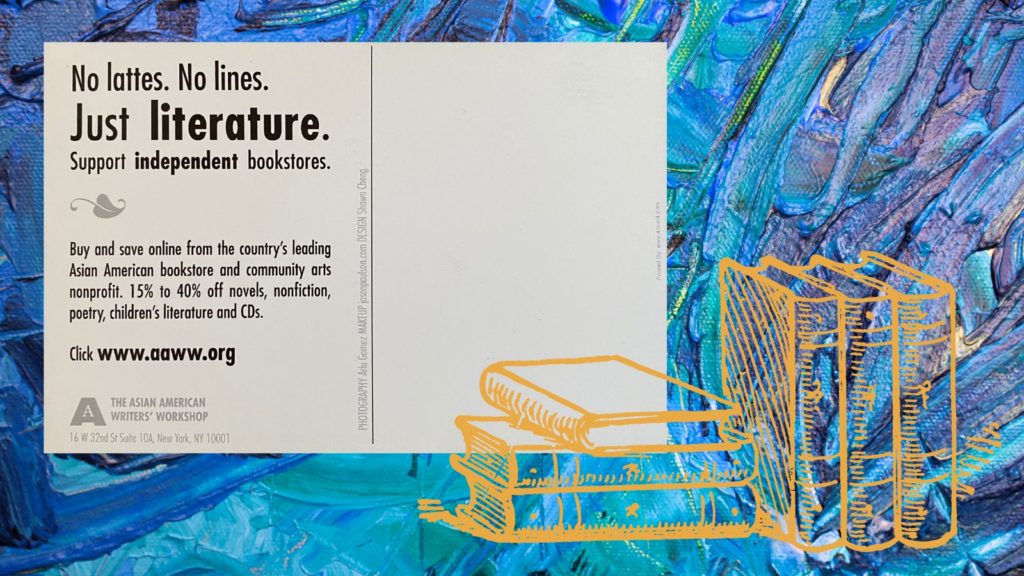

All the while, Barnes & Noble and Borders were our biggest competitors—Amazon was not yet a thing. We took the bookstore online in a bid to compete with the chains, revamping the website and sending out a blitz of postcards calling on folks to support our independent bookstore. That run lasted a couple of years until the bookstore closed and was converted into a reading room. I wouldn’t believe you if you told me then that Amazon would be the ultimate behemoth and that today we’d be in an independent bookstore revival.

I was about 22 when the Workshop celebrated its 10-year anniversary. A decade seemed like such a long time to me, being roughly half my life at the time. Congrats to the Workshop for making it to 30—here’s to many more!

Arvin Ramgoolam, Owner & Founder, Townie Books (2009-present)

414 Elk Ave, Crested Butte, CO

I didn’t want to read Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies. I was in my teens, it was the late 90s, and I worked at the Russian Bear Cafe inside Books and Books in Miami Beach. Almost everyday, a woman would dictate my identity to me and exclaim, “You have to read it!” As an Indian from the Caribbean, I didn’t know where to find myself on the bookshelf. Lahiri’s book would sell millions. What did it matter if I read it or not? In those days, there was a mere smattering of Asian authors on the bookshelves. Amy Tan. Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. Arundhati Roy.

None of their books felt or sounded like me. With skateboard in hand, my backpack was filled with books like Fight Club, Selected Poems of Neruda, and Ghost Soldiers. There was room for Lahiri. But I wasn’t ready yet. I was graduating high school and unconsciously beginning the work of decolonizing my mind. Edward Said’s memoir, Out of Place, and Vijay Prasad’s The Karma of Brown Folk had just landed in time to save me. Without those books, without the bookshop, I would have never entered college considering what it meant for someone like me to grapple with the inescapable feeling of otherness I would experience in my life.

Working at a bookstore would leave an indelible mark on my life. Amazon was difficult to imagine as a replacement for bookstores. It would be almost 20 years before booksellers regained their footing as blue collar intellectual vanguards of culture around the corner. The same amount of time it would take me to find an Asian American community among writers.

Today, I am proud to be among almost 30 AAPI owned bookstores in North America. Libro.fm, an independent rival to Amazon’s Audible, took it upon themselves in the wake of horrific attacks on Asian Americans in 2021 to compile a list of AAPI bookshops across the country. I was heartened to discover bookstores like Bel Canto Books in Long Beach and Eastwind Books of Berkley. I was not alone as an Asian American in my passion for selling books and taking the chance on opening a business some consider foolhardy.

I wish I could tell that 18-year-old kid who lucked out working at a bookstore in Miami Beach to stop being such a shithead and not wait to read Interpreter of Maladies. He eventually did, spending the next two decades rereading it as a writer and using it as a bridge to other books that communicate the Asian American experience among the growing list of authors in the bookstore.

People are returning to bookstores and valuing what we do in the face of an internet behemoth prophesied to destroy us. So many of our stories are on the shelf now. Antiman by Rajiv Mohabir, and Brother by David Chariandy are the Indo-Caribbean books I’ve waited for since my first reading of V.S. Naipaul’s brilliant but self-hating novel, The Enigma of Arrival. Those books are an antidote for writers like myself, contending with both our Caribbean and Indian heritage and the effects of colonialism. Kazim Ali’s Northern Light, Nawaaz Ahmed’s Radiant Fugitives, and Sanjena Sathian’s Gold Diggers are all books by Asian Americans that could not have come at a more urgent time. These books ask the big and bold questions of where do we belong and how do we fit in? Cathy Hong Park in Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning underlines, “writers of color must tell their stories of racial trauma, but for too long our stories have been shaped by the white imagination.” We face the future and require our own imagination to see ourselves in the American story. We belong everywhere.

I finally found myself on a bookshelf of my own making. But now, I’m a father, looking and thankfully finding children’s books like Looking for a Jumbie by Tracey Baptiste, Bindu’s Bindis by Supriya Kelkar, Festival of Colors by Kabir and Surishtha Sehgal, Where Three Oceans Meet by Rajani LaRocca, and What I Am by Divya Srinivasan. These books celebrate our culture and fill me with an urgency on behalf of my biracial twin girls who contain within them the blood of both the colonizer and the colonized, who will face the same questions of belonging I did and likely more. I am thinking of a lifetime of books for my daughters. I am thinking of how I want to introduce them to Interpreter of Maladies. And, I’m thinking of how to help more people find themselves on the shelves of my bookshop.

Jeannie Wong, Administrative Director, AAWW (1998-2009)

37 St. Mark’s Place + 16 West 32nd Street, New York, NY

Flashes of memory

A classmate handed me the AAWW Bookseller Catalog after our “Asian Americans: the Movement and the Moment” class at UMass Amherst; I poured over it that night, then made a special trip down to New York.

Administrative Director also meant I had to run the Bookstore (until Nancy took over!)

Packing tape, the UPS guy chatting on the payphone

Working with NYU/Hunter/Columbia professors, ordering books from distributors, paying the invoices when we could

Self-published memoirs, hand-bound books, “Inevitable” by Pinay, Korea Girl T-shirts

We dropped everything to read the newest A. Magazine.

Dusting shelves, helping frantic students with their final papers, lugging bins of books to sell offsite, tabling at conferences, photocopying bookmarks

Book launches and parties, ordering printed black canvas tote bags, buying way too many books, getting autographs from numerous authors

The moving company with their countless small boxes for books, custom wood shelving for the new 32nd Street space we moved into, even more inventory

Lounging in the maroon velvet chairs, the little grey couch left on the street, the IKEA coffeetable

Starting to sell online, our postcard campaign (with Corky, Edward, Margarita, Moustafa, Pimpila, Rekha), budgets and plans, fighting to stay

Lucy Yu, Owner, Yu and Me Bookstore (December 11, 2021 – present)

44 Mulberry St, New York, NY

As I open the doors to my bookstore in New York City’s Chinatown and look around at the stories that fill the walls, my own story is deeply embedded. I feel my mother, my grandmother, and myself in every nook and cranny of the space.

When I was visiting China in 2014, I watched my grandmother’s trembling hands scratch Chinese characters into her journal, squinting through her fading vision to reread a passage and check her work. She has kept every single journal she’s ever written, marked by daily passages and dates, for more than 60 years. She passed this trait down to my mother, who then passed it down to me. My mother’s daily record keeping took a detour when she raised me as a single mother, but once I left home for college, she resumed her paper trail. I started my own obsessive daily journaling practice when I was 16, following in both of their footsteps.

My grandmother taught at the same school for most of her career and then became the first woman principal there. She is incredibly smart, innovative, and dedicated to whatever task she takes on, and I can see that even through our broken communication. She published a book around 10 years ago, and my mother told me that she was already starting to lose some of her vision at the time while still trying to type out Pinyin on her desktop computer.

During the Cultural Revolution, my mother was forced to work in the farmlands of rural China. She had to search for an alternative way of life, which led her to graduate school in Canada, and eventually to building a life for us in the United States. I think of how hard that must have been—to be the mother of a child growing up in a nation foreign to you and watching that child absorb a culture that wasn’t yours. I think of her waiting for my father to come back to the United States after he decided to move back to China to start his own business. I saw that hope fade when she eventually realized that he was never going to come back. My mother always says that she isn’t smart, that she has never been good at much, but anyone that has ever met her would say the exact opposite. A few years ago, she wrote a short memoir and spent her evenings translating it from English to Chinese just so that my grandmother could read it, too.

In my bookstore, I see stories everywhere similar to my family’s private journals. I see my mother’s quiet resilience in Sunja from Pachinko by Min Jin Lee and my grandmother’s strength in Diệu Lan from The Mountains Sing by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai. I feel how intertwined and connected all of our stories have become. We share in histories similar but unique. Every morning, when I pull up the gate, walk in, and turn on the lights, the feeling of home illuminates.