From its very beginning this story is fated to be exposed by the light.

December 6, 2017

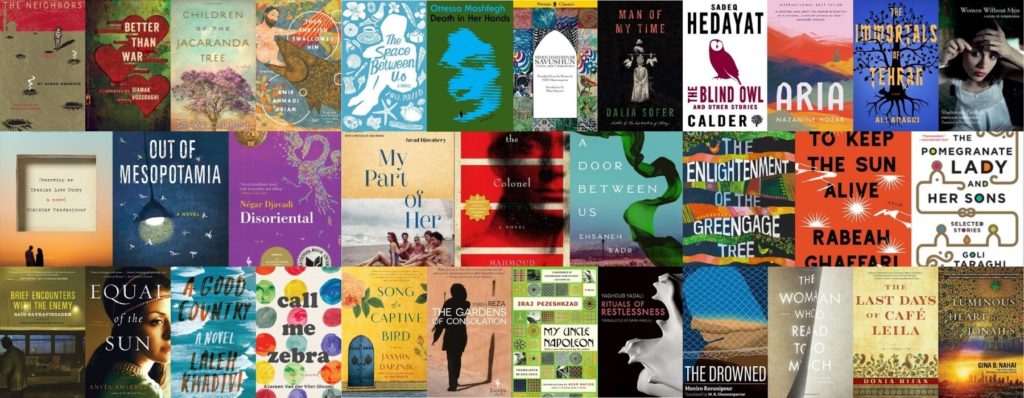

From the lack of rain to the dripping faucet and sweat-drenched clothes, this story is awash with liquids of all kinds – but more than that, the narrative itself is pure fluidity. In Joshua Dyer’s deft translation, Li Zishu’s uncanny Malaysian tale takes us through a strange encounter in an arid town.

From the lack of rain to the dripping faucet and sweat-drenched clothes, this story is awash with liquids of all kinds – but more than that, the narrative itself is pure fluidity. In Joshua Dyer’s deft translation, Li Zishu’s uncanny Malaysian tale takes us through a strange encounter in an arid town.

Rainless Town – Monologue

by Li Zishu, translated by Joshua Dyer

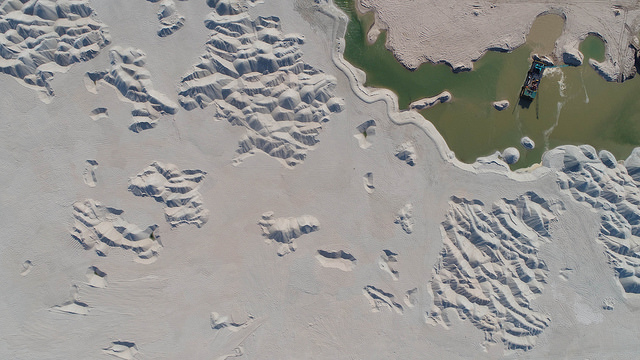

So strange, this rainless April. The sunlight exhausts its manic phase, only to turn strident and self-destructive, nearly suicidal. All things come to an end. Some by melting in the ferocious heat.

The light is acidic, irradiated, liquid; it is silent and deafening; tasteless and overpowering; formless and formed, this light. Day and night it shines, boundless, endless, unceasing. No clouds. No rain. No thunder. No lightening. The light comes down in torrents, buckets upon buckets without end, like all of God’s half-written stories beginning with creation itself, the official histories and the unofficial, everywhere, in every place, magma-esque, hissing and seething.

From its very beginning this story is fated to be exposed by the light. The prostitute (you) open the window. This light I’ve been talking about rushes in like a wave, covering everything, so fierce it seems to roar. April. Nearly noon. The prostitute bathes in the spectrum; your extraordinary beauty is nearly transparent. The light consumes flesh. It enters. It pierces. Your moist and tender skin immediately burns. So strange, this rainless April.

Yeah, why doesn’t it rain? The traveler (I), bury my head in the pillow. The sky is bright. The sun is burning. Why hasn’t she left? I imagine you twirling on your black coat as you return to your damp fungal coffin. The prostitute doesn’t leave. She lies down again. Last night you said you were sixteen. Did I? You stood near the window and immediately your body filled with solar energy. Your fevered breasts seared my long, fractured spine. Oh, I forgot to pay. I forgot you were a sixteen-year-old prostitute.

What did you come here for? Old hotels are full of mold. The stairs always creak. The faucets don’t seal properly. Drip, drip. Drip, drip. Has the prostitute (you) left? Have your sixteen years departed? Last night I sucked down the last dewdrops of youth. What am I doing here? My head hurts. My ears ring. I hear a man sobbing, repenting in the moments before death.

Someone else is playing the prostitute now. Someone with darker skin. Someone a bit saucier, more ruthless. She died, that sixteen-year-old from the other night. Oh? Her sixteen years died young. The prostitute speaks in retroflex Malay while licking the back of my ear. She asks what’s in my hair. I turn my head to tell you it’s something my father left me, his Ancient Dragon cologne. I have his sweaty shirts and underwear, his pawn tickets, some leftover Thai baht, his checkbook, his aphrodisiacs. The traveler empties his luggage, revealing a collection of objects so motley that no two of them seem remotely related. I don’t recognize any of them. The traveler says, like a pickpocket, I never know what I’ve got until after the fact. The prostitute’s sense of humor is deficient to the point of disability. She picks up a paper package saying, these are fake. They don’t work. You’ll get it up but it won’t last.

It’s true. They’re all fake. The prostitute’s boobs are fake, her age is a lie, false eyelashes, dyed hair. Not bothered in the least, she says, hah, even my ID is fake. The traveler thinks this April sun is too damn bright. Like a sharp knife, you don’t feel it pierce your skin. It dissolves into your blood. You only become aware of it when it begins to heat your plasma. The light floods through the window and smothers you. You gasp for breath. You grow dizzy. Suddenly, you want to kill the prostitute. You’re excited by this impulse. The traveler (you) crawl out of bed still naked. The April light is greedy, voracious: it leaps forward to gnaw at you. You’re scared. The mirror on the wall reflects the light, illuminating the prostitute as she lights a cigarette. The prostitute has changed again. This time even her sex is a lie.

I came here looking for someone. Ever come across an old man from out of town? The old man is the traveler’s father. The traveler struggles to remember him, to describe him. Did he ever visit you? He’s old, but he still wants it. He’s got herpes. He reeks. Doesn’t bathe for days on end. Always broke. The prostitute removes her false eyelashes, her false teeth, her wig, her false boobs. In that instant she looks just like my mother. The prostitute says, don’t ask me anything, just hold me.

The traveler is passive that night. The prostitute mounts him, and then crawls down below, sweating from her exertions. What were you doing when you were sixteen? Were you working on the rubber plantations? Were you married? The traveler continues to talk in his sleep: My mother first slept with my father at sixteen – the same age as his eldest son.

The prostitute is old now. Last night she was sixteen, in the flower of youth. When I awake I find a grey hair on the pillow. I am still a traveler, same as before. The prostitute has left her false teeth in the bathroom. They look like a mouth that might go on talking forever. The traveler vaguely suspects he may have killed the prostitute. The teeth ask me what happened to my mother and father. The traveler says, I wander town to town, just like my father fucked from one woman to the next. He must have come here; I can smell him. The false teeth aren’t paying attention. They smile enigmatically.

Prostitutes don’t make good listeners. If I’d been given a choice of keepsakes, the traveler thinks, I would have taken an ear over teeth. The prostitute laughs then falls asleep, faint smile lines on a face aging too young. The prostitute says I took my first john at thirteen; who cares about sixteen? The traveler is sitting in bed smoking. The traveler is naked. The traveler feels the hotel room is sinking into a hole. He turns his head to watch the prostitute aging in her sleep. She sleeps soundly, as if dreaming of her lover’s breast. I left home at sixteen. I spat a gob of phlegm in my father’s face. Fuck your mother, you horny bastard. So many have died, but somehow you’re still around. Would you (the prostitute) believe it? He climbed to our neighbor’s balcony in the middle of the night. Climbed right into the widow’s bed.

The traveler was young then, only sixteen. The prostitute lovingly kisses his forehead. So, you just hop off the train at whatever station comes along? The traveler feels lost. Choo-choo train, choo-cho train, hear the whistle blow. Choo-choo train, choo-choo train, where you gonna go? A children’s game he used to play, like Eeny-meeny-miney-moe. Catch a tiger by the toe. If he hollers, let him go. Eeny-meeny-miney-moe. The traveler says, I want to cry. Will you tease me if I cry? The prostitute is exquisitely gentle, maternal in every way. Cry, if you want to, cry. Let me hold you.

Never in his life has the traveler met anyone as low and shameless as his father. What did your father do? The traveler hears himself whimper. He didn’t do anything. He was just another traveler. The prostitute holds him close. Why did he travel? Was he looking for someone, too? My mind goes blank. I bury my face in her ever-so-slightly sagging breasts, but I can’t detect the scent of my father. Every footstep in the hotel stairwell seems to signal his arrival, or is it his departure? Sometimes the footsteps stop outside the hotel room door. The traveler waits for a knock, but it never comes. The traveler can faintly hear heavy breathing, like the gasps of a dying animal. It’s as if the footsteps are conspiring to play tricks on me. There’s the flap-flap of a sick man’s slippers, interspersed with the hacking up of phlegm; the tap-tap of old leather shoes, one beginning to split at the sole, an old gambler returning from a losing night of mahjong; the sound of something creeping barefoot down the hall behind him, the gambler’s aged soul, reeking of rot and decay.

If only it would rain. The traveler and the prostitute are covered in the scent of sweat. He remembers he once stopped in a town where it always rained. I remember the scent of fresh chicken crap; papayas dropping from trees nearby, imbued with the maternal, like your breasts. The overripe fruit lay in the grass. The vaginal orifices pecked by men with bloodshot eyes were now rotten and speechless, gathering rainwater. You degenerate, she giggles. The traveler opens his eyes. The prostitute is sixteen again, or thereabouts. Her face is plastered with makeup. The traveler finds it unbearable. The room is too bright. The ancient air conditioner coughs and wheezes without end.

The prostitute glances at the traveler as she leaves. He is seated in a corner clutching his knees, his eyes fixed on some point outside the window. There is nothing there but fierce, ubiquitous light. The newspaper he was flipping through has yellowed a shade. A presentiment of death congeals in the stagnant air of the room.

One night the traveler isn’t in the mood. The prostitute is having her period. The traveler is lost in thought, working his way through two packs of cigarettes and two cups of coffee with cream. Brooding like that gets expensive, doesn’t it? The traveler doesn’t think it’s funny. Isn’t it strange? Since I left that town where it always rained, our country has dried up. Our country? The prostitute shrugs her shoulders. You’re wrong there, sugar. I’m from Java. A Javanese tranny, with an Adam’s apple, rough skin, and a raspy voice. I guess you can’t read my novels, then? My father dies in one of them. The scene is like something from real life. He can’t come to terms with death. His eyes are filled with cataracts.

Eyes, ears, and false teeth. No matter how these heirlooms are thrown together, they fail to create the impression of my father’s face. It’s a shame my manuscript was rejected, the traveler says. My father would have read it and died of anger – if he isn’t dead already. It might have happened in this very room, or in that corner room at the end of the hall. The prostitute speaks, her voice masculine: I feel sorry for you. All your crazy fantasies. The traveler thinks nothing is real. You’re a tranny, how can you be on the rag? The prostitute turns and exhales sharply. A tranny? The sunlight boils over. The prostitute rubs at the streaks of menses on her inner thigh. What are you using to wipe up that up? The prostitute tosses the crumpled ball of paper towards the wastebasket and misses. Just some scratch paper. Look, that’s your writing stuck to me.

Fragments of the traveler’s novel have been transferred to her thigh: “this rainy town… searching… the shadow of a man… papaya,” then some indecipherable symbols, extending upward into the tangle of her pubic hair. I couldn’t find the words, just like I can’t find my father. Surely he’s just looking for some place to hole up and die, like some wild animal. Forget about him, my mother told me, you’ve always wanted him dead anyways. He’s had his days of eating, fucking, sleeping. Now it’s time to die. What is it you’re searching for? What do you want to know?

The traveler thinks how wonderful it will be if the words never fade. Every time she opens her thighs my novel will be there, like a tattoo, a talisman. One day his father might read it. He will prematurely ejaculate, and then go digging through her pubic hair for the rest of the text. The traveler enjoys daydreams like this. Two travelers, each searching for the other, each a mirror reflecting the other’s image. An endless search, town after town, the railroad tracks following the border and then looping back in a giant ellipse. Our wandering will never cease, my father’s and mine, like the rain in some town that never stops falling. We are avoiding each other, actually, but we accidentally leave clues for the other to find, reaffirming our mutual existence.

Of all the prostitutes only the tranny’s hair is so long, like a waterfall, or a streak of Javanese jungle slashed and burned for planting. Her perfume is cheap, but the traveler thinks this the most maternal of scents. He most enjoys watching her, after their business is done, as she smokes in front of the cosmetics mirror. At that moment they are alone. They belong to themselves, each in their own space, silent and narrow. Disordered parallel universes, never intruding on the other. You have your Java, prostitute, and I have my endless journey.

After a few days the traveler decides to leave this town drenched in light and heat and head north on tomorrow afternoon’s train. At night the traveler sets out to find the prostitute who had brought her entire Javanese village with her to this foreign land. A prostitute squatting in a dark alley says, that tranny you’re looking for is dead, a john choked her to death, don’t you read the papers? The traveler wonders if it’s true. The traveler stands dumbly in the dark alley. Finally, in this rainless April, under this burning sky, I feel a touch of cold. Did she leave anything? Under the faint hiss of the streetlamp, the prostitute’s face blurs as she leans forward to whisper in the traveler’s ear, what do you think she had? The only thing she owned was a wig.

That night he dreams of a vast emptiness from which the sweltering heat spills forth. He awakes drenched in sweat, dimly aware that he is no longer in the same room. More than likely this isn’t even the same hotel. The only thing unchanged is the extraordinary heat, indistinguishable from the night before, arid and stifling, the wrath of the heavens. The traveler licks his cracked lips. His head hurts. His ears hum with what seem to be confessions filtering through the wall from an adjacent room. Father, I forgive you. The traveler writes these words again and again on draft paper, as if doing penance. I forgive you. I forgive. The prostitutes’ voices sing out together – the masculine voice of the tranny, his mother’s sob-wracked whisper – they well forth from the depths of his mind like a symphony composed of all the sounds of nature. We forgive you.

The movie theater is playing an old film that no one remembers. The traveler buys a ticket, but doesn’t enter. He is struck by the presentiment that his father will be seated inside, too close to bear. It’s daytime, and the prostitutes, unable to work, will also be there, seated in a row passing chips, soda and popcorn. He guesses they’ve all seen the film a dozen times, but no one remembers the characters or plot. They watch it only to forget the previous viewing. The traveler is only one of many johns. Upon reflection, he is also just one of many travelers, none of whom actually exist. He sits on the steps of the theater sipping soda and eating popcorn.

The traveler must continue his journey, which requires only that he change towns, hotels, rooms, prostitutes, train stations, but I cannot change my father. Before leaving, the traveler calls a newspaper. The editor says, sorry, your novel doesn’t ring true, the setting feels fake, the emotions are forced. The traveler offers to rewrite it: the prostitute doesn’t have to die, only my father. April light pours down from above. The telephone booth might boil and evaporate. The traveler hangs the scalding receiver on its hook, turns, and flows into the thick liquid heat.

The traveler squeezes onto the train, and the engine starts chugging along. So strange, this rainless April, the woman behind him says. What god-forsaken weather. The traveler takes a folded piece of draft paper from his backpack. On his knee he writes the first line, “So strange, this rainless April.”