Most of us who love the past live among what remains.

December 21, 2022

I have often wondered if when we begin to love, we begin to mourn immediately. Some people can do that thing, that thing others tell me to do and I wish I could do: be in the present. People who can always be in the present, if that is you, may I ask: what is it like to be so good, to have dewy skin, to have a digestive system as smooth and dependable as the train schedule in Berlin’s Alexanderplatz?

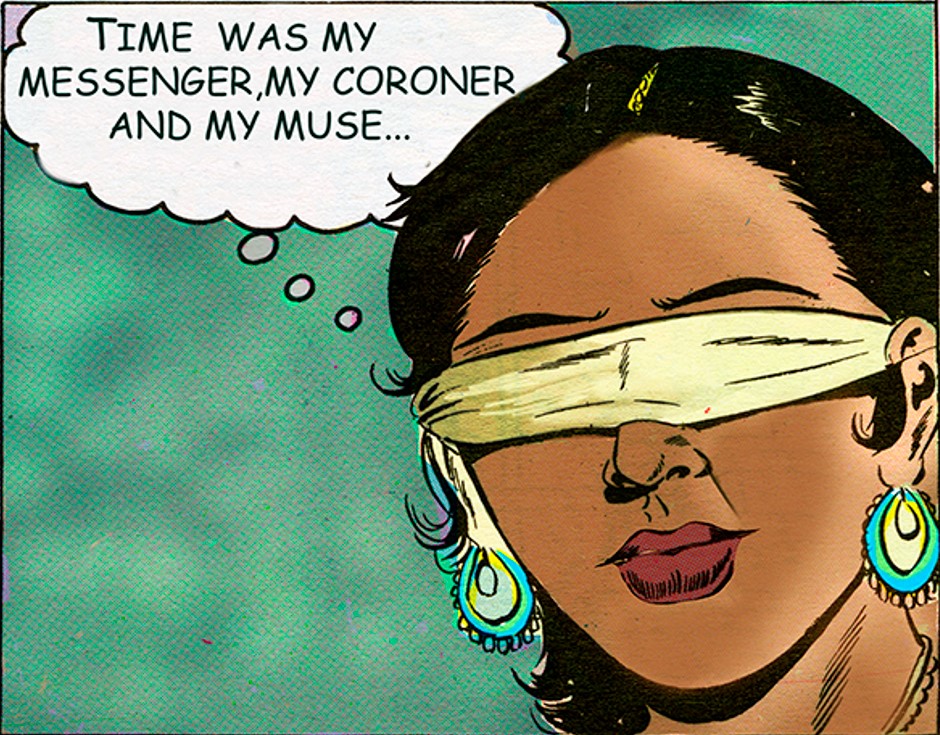

Meanwhile, some of us prefer shards of memories, fragments of things said, and most importantly, the things that we should have said because we are constantly reliving our past, like a Super 8 mm film that flickers with possible futures. Some of us like the frosted looking glass of the past, the coulda-woulda-shouldas of alternative flashbacks, sentences that start with a past participle, and nested clauses. The past is a home where we gather memories, fantasies, and versions of ourselves. Most of us who love the past live among what remains.

In The Margins’ first flash fiction notebook, Remains, we gather fourteen stories by writers who also dwell on the remains and what is left when those we know depart. In these stories, writers confront loss, grief, and the remnants of the ones we know, whether it’s a postcard or a memory or a ghost. Each writer urgently asks: after leaving, what remains?

I remember the finality of the moment when my father pressed the button at the crematorium. My grandmother, whose embalming was both lifelike and deathlike, taught me about remains. She was a scrappy immigrant, a person who literally used every scrap—cleaning rags, doll clothes, hair bows. Past-prime dairy would become paneer, and old tubs of butter and cream cheese would hold minced garlic and ginger. And she had a scrappy disposition—when she was seventeen, she was a refugee during the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, among an estimated fourteen million other refugees. Bringing only what she could carry, she brought a satchel of books across the border so she could study for her final high school exams.

I got my love for thrifting from my grandmother, though she hated that I bought other people’s old clothes. She wanted us to extend the life of our belongings as long as possible. Years ago, I bought a sage green Eisenhower-era A-line wool coat with a light gray fur collar. When I wore it, I looked like an indie brown girl into alternative rock. It was the nineties. But when my grandmother wore the coat, it was a vibe, and she was transported to an alternative life. Maybe if Shonda Rhimes produced a show set in 1950s Chandigarh, my grandmother in this coat would be the chic Indian woman leaning against an Ambassador car at the dawn of a new nation. I imagine a horizontal possibility where my grandmother has the kind of life that middle-class white American women in the 1950s who voted for Eisenhower may have had. Because of the strange verticality when I wore the coat, I gave it to my grandmother to have and wear. She wore it until she died. It’s still in the closet, in case my soon-to-be-teen daughter ever longs for it. Sometimes I wrap myself in it and try to smell my grandmother—her hand cream, sizzling tadka, alma hair oil. In reality, I smell professional dry-cleaning solvents, the mustiness of storage spaces, and decades of people who wore the coat before it reemerged to be worn triumphantly.

When flash fiction assistant editor Yi Wei, series reader Ghinwa Jawhari, and I read flash submissions for The Margins earlier this year, we saw that ghosts and the remains of things lost populated many of the stories. Wanting to put these stories in conversation, we brought them together in a notebook. Ghosts and loss are evergreen topics in Asian diasporic fiction, but it’s not entirely unexpected these stories surfaced while many of us are dealing with loss and change from the pandemic.

COVID-19 brought a different sense of mourning and remains early in the pandemic. My father-in-law’s sister died in March 2020 from respiratory failure. A family friend who was an infectious disease doctor died in those early days as well, because hospitals didn’t have enough PPE. A year later, when the Delta variant swept India, my uncle passed away. He was about to get the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine when he tested positive for COVID. As a collective, we all carry these stories of losses. And the losses of COVID are not just the rising death toll, but also the loss of empathy and reason, the politicization of masks and vaccines, and time. We lost time to gather, to grieve, and to mourn.

My grandmother died in 2018 at the age of eighty-eight. When we first became aware of COVID, I remember being grateful that my grandmother died before the time of quarantine. I often think about the intention and care of her last years as months of her life, and see it as a model of how a life is well-lived, and may I say it, how a death is also well-lived, curated, and meaningful. My grandmother knew she was dying and summoned people to her, asked for forgiveness, was able to give, and received blessings. She died at home under the care of truly wondrous hospice nurses and her son, my father, who as a doctor managed her care so she could be at home. In the last month of my grandmother’s life, my mother played my grandmother’s favorite devotional music as she entered in and out of a dream state.

The week before her death, we knew it was imminent and asked people to fly in. As my grandmother was in a comatic state, we took turns being with her. I started writing her obituary, and my parents and siblings edited it. We compiled photos for the funeral and remembered moments when we were all younger and less weary. In that last week, we were gathering, creating, writing, and curating.

One Friday afternoon in November, I promised my daughter that we’d go out for ice cream at the local cow-to-cone shop. I had a feeling to check in on my grandmother before we left. She was stirring when we walked in. And I called people to her. Her family ran and gathered. Everyone surrounded her, and she woke up for one second and stared at those who loved her, their hands in her hands, their hands on her body. For a few seconds—a startling suddenness, her eyes wide open—and then a descent to the finality of death.

It could have been a scene from a movie, but it was real. As my father called the coroner, I was told to take my child out for ice cream after all. My daughter had soft-serve chocolate vanilla with rainbow sprinkles, and I had a seasonal maple-infused flavor.

That November ice cream date was a #momentofbeauty—a hashtag I learned from my dear friend Rachael Wells. While she did not coin the hashtag, she popularized it among her friends by telling them of her moments—leaves falling, melting ice cream cones, sunsets over Riverside Park. A loving mother of two young children, she was diagnosed with glioblastoma about a year into COVID and died in June 2022. Online she chronicled her diagnoses, treatment, and reflections on death and dying, which are actually thoughts on living.

When Rachael told me one day at the beach that she didn’t have the brain capacity to read novels anymore but that she missed the immersive world of fiction, I read some flash fiction aloud to her from The Margins. Always hilarious, she said, “Your flash series is great for people with brain tumors.” We need more stories about dying, creative rituals, and anticipatory grief and mourning where we brace ourselves, Rachael told me. She was teaching me, and the community that cared for her, how to curate one’s final days with grace, beauty, and creativity. One of the last conversations we had was about all the great “ghost stories” that would become this notebook, as she loved to cheer on her creative friends and hear all about our projects. When I first encountered the stories in this notebook, I imagined reading them aloud to her.

In her book Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work, the Haitian writer Edwidge Danticat said that immigrants—I’m paraphrasing here—are artists because our lives are constant creations based on dreams. We who live in diasporas—whether by forced migration, global inequity, or colonialism—make our lives with shards from our family histories or different homes. Writers use remains.

Many of the stories in the Remains notebook hold tender the remains of the present moment. Each story does something astonishing and different.

Speaking to the moment of pandemics and the remains from mass cremations, “Ash” by Aathma Nirmala Dious depicts the plight of migrant workers and what is lost when (mega)cities are built, resonant at this very moment thinking of the World Cup in Qatar. Taipei, as a city of ghosts who remain after the violence of migration, is at the heart of Sheng Kao’s “Ghost Month Zuihitsu.” In “Haunted Penthouse,” Urvashi Pathania excavates the remains of luxury condo architecture and the ghosts among them, hilariously and poignantly revealing the tale of two cities in New York City. In Yasmine Rukia’s “Flight of the Buraq,” home is a place always enmeshed in loss that asserts itself even more when one has left.

Other stories take on the idea of place by illuminating how the remains of neighborhoods connect to our family stories and our younger selves. In “Two Small Hands,” Zen Alladina shows how gentrification is also a form of death, how we can’t go back to our childhood neighborhood because neither the neighborhood nor the childhood exists anymore. Tony Wallin-Sato’s “The Funeral” captures the hectic, frantic vibes of a funeral gathering, which can be both disorienting and comforting. In “Little Crane” by Juliet Way-Henthorne, the speaker tells the story of their grandfather who flees a country and recounts the loss of the boy in the present of the old man. The act of dying, in Elane Kim’s “Postcards,” is to get smaller, raising the question of what remains when the body embodies less space.

Remains assume different forms in stories that play with fables and fabulism. In the intergenerational “Give Me an EpiPen for Resurrection,” Abhigna Mooraka reveals the different animal forms human bodies can take and how inheritance is an especially loaded type of remains. In “The Omen,” Cleo Qian asks what the death of koi fish means in a world where elements have lost power and yet omens are around us. The extremely charming crab-girls in Mandira Pattnaik’s “A Crack in Their Porcellanidae Shell,” show us another kind of death when there is a desire for freedom and a loss of freedom.

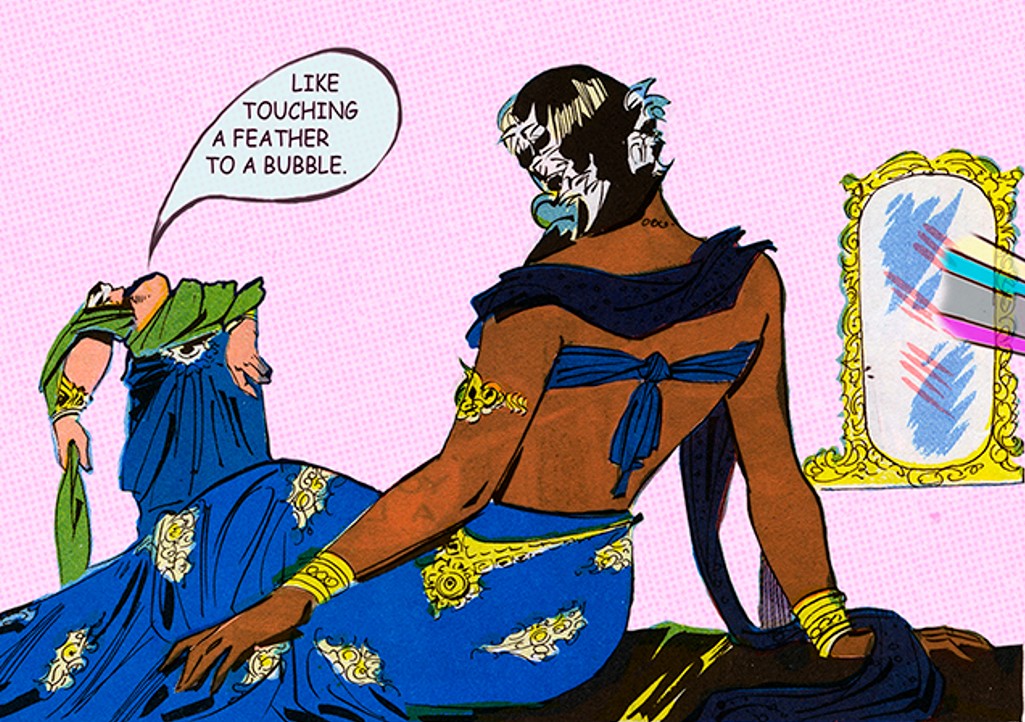

Many stories in the notebook incorporate the sense that we begin to mourn as soon as we start to love, anticipating the firsts and never knowing which will be the lasts. Sijia Li, in “Tender Is the Ghost,” describes what remains in the ways that we, and lovers, touch our body. The loss of love in SJ Han’s “Blue Stripe” comes after a moment of incredible luck. Lilian Liang, in “Three Reincarnation Rituals,” asks how any of us finally return home to ourselves. Is it through relationships or rituals that affirm the self?

In times of overlapping mournings and losses, making sense of what remains can be a lifeline. We hope you find comfort, poignancy, rage, solidarity, and good, good, cozy company with these stories.

This introduction, and really the genesis of the notebook, is dedicated to all the dear ones we collectively lost in the past few years, including Anantha Sudhakar, Anthony Imbornone, Anthony Veasna So, Elizabeth Smith, George Bumbray, Greg Tate, James L. Moore, Kamilah Aisha Moon, Kimarlee Nguyen, Krishnan Ganesh, Maurice Berger, Priyanka Mathew, Pushpa Khurana, Rachael Wells, Sanjeev Jaiswal, Satya Malhotra, Susham Bedi, and William Gregory Draddy.

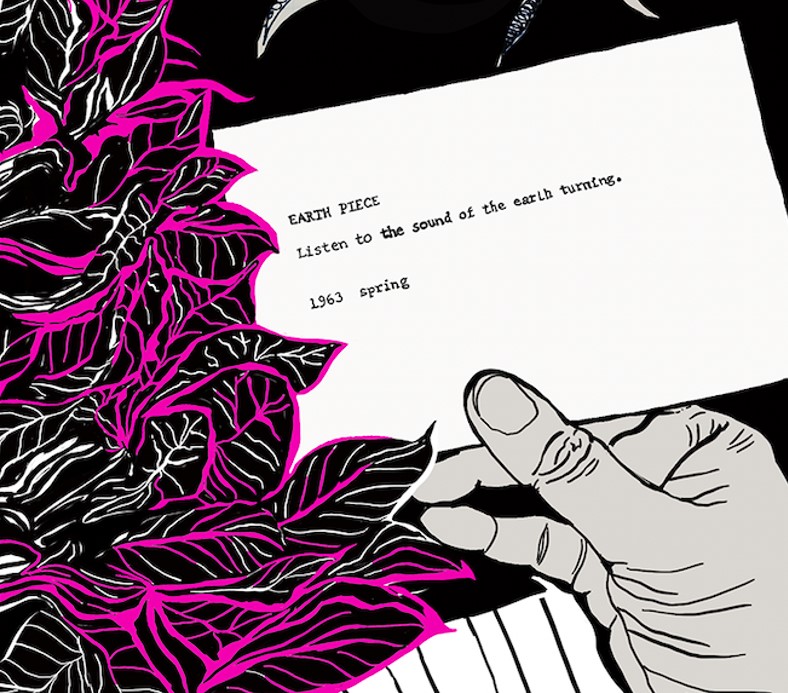

This piece is part of the Remains notebook, which features art by Chitra Ganesh.