What does it mean for a Palestinian living in the United States to resist?

June 20, 2019

There are no clouds today, and so New York is happy.

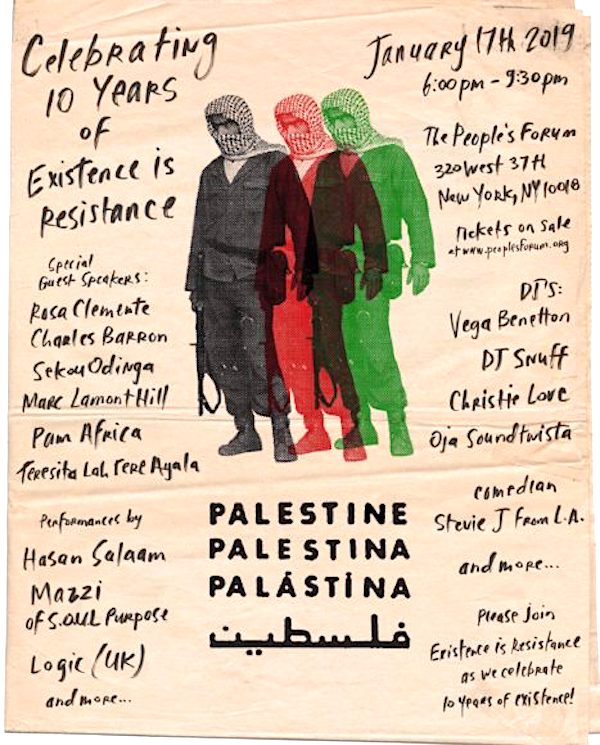

I board the Manhattan-bound R train on 86th street in Brooklyn. It’s the middle of March 2019, and Within Our Lifetime, an activist group born of the New York City-wide chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine, is hosting an event to celebrate Palestinian culture and resistance.

Though the latter name better characterizes the group’s spirit — well-educated and anxious, nervous about the future but willing to try to shape it — Within Our Lifetime more directly reflects its hopes and motivating principles. It’s a declaration that during the lives of its members, a liberated Palestine is inevitable.

What liberation is, what it actually means given the current geopolitical realities of the Middle East, is unclear.

I exit the R on 36th Street and wait to transfer to the N. I unconsciously pull my phone out of my pocket, and I drift to Within Our Lifetime’s Instagram account.

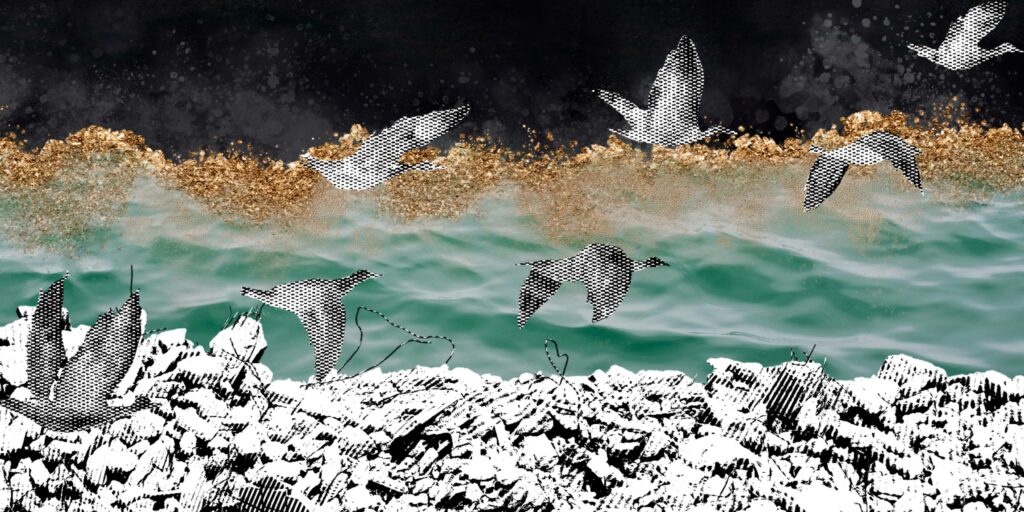

The images are familiar: Revolutionary posters from the 1960s and 1970s; screenshots of digital headlines or news articles germane to Palestinian activism; videos of cultural performances, some in celebration, others in protest; photos of martyred Palestinians; etcetera. In one, a legless man rests on a patch of wet sand, jean shorts covering his knees where his legs were blown off at an earlier demonstration, a cap on his head, a Palestinian flag in one hand, the pointer and middle fingers of his other hand in the shape of a V.

Within Our Lifetime represents a cross-section of the global Palestinian diaspora in general, and the U.S. Palestinian diaspora in particular. As a whole, the global diaspora is rich and varied, spanning multiple continents, classes, and experiences. In recent decades, it ceded its historic position at the vanguard of Palestinian liberation to Palestinians living under occupation (boycott, divestment, and sanction campaigns notwithstanding.)

And as well it should have. It’s Palestinians currently in the West Bank or Gaza, or those languishing in multi-decade-old refugee camps, or those living as second-class Arab citizens of Israel, who have to face continuous slaughter, displacement, imprisonment, and apartheid. They ought to lead efforts to ensure their liberation, if only because they have the most to gain materially.

And yet the diaspora requires serious consideration, both as a political entity and as a space for cultural preservation and security. Palestinians who live free of occupation, who carry passports allowing them to travel freely and which confer upon them the rights and privileges of citizens belonging to stable and sovereign nation-states, continue to shape the global discourse on Palestine and on historical injustice. Understanding what the diaspora is, and the various roles that diaspora Palestinians play with respect to one another and with respect to the goal of Palestinian liberation, is necessary if it’s to ever become the force for change, indeed the force for return, that its members wish it to be.

(Though there certainly are sociopolitical, cultural, and economic overlaps between the diaspora in the U.S. and the diaspora elsewhere, my experience is almost exclusively limited to the former. And so I draw conclusions regarding its future and m.o. without assuming their applicability to diaspora communities elsewhere.)

◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎

I maintain that the most important question facing the Palestinian diaspora in the U.S. at present is that of its boundaries and, by extension, that of its limitations. What does it mean for a Palestinian living in New York to resist? To the extent that he or she works and pays taxes to state and federal governments which directly fund Israeli apartheid, what does resistance mean coming from a Palestinian who contributes at least indirectly to the subjugation of his or her people?

The University of Reading’s Bryan Cheyette envisions diasporas as composed of both the amalgam and the regressive — people defined by the experience of synthetizing cultures and languages on the one hand, and by the desire to return to an unchanged, unadulterated space on the other. In his Diasporas of the Mind, he constructs this experience along a spectrum: “At one end … diaspora is on the side of impurity and hybridity … and at the other end, diaspora is conservative and ‘roots-defined’ and has as its end-point a return to an autochthonous (pure) space.”

It’s the young Palestinian who was raised in the American Midwest, who understands Ramallah’s cultural markers as well as she does Chicago’s, and who code-switches seamlessly between the Arabic of her home and the Americanese of her school or workplace. It’s the young Palestinian in New York, who sports the cleanest Js and D’Angelo Russell jerseys, who drops the n-bomb and sounds like Cardi B when speaking English, and who switches to the most rural of Palestinian dialects at home, where filial piety is taken for granted and respect for the parents is paramount.

In Diasporas, Stephane Dufoix offers a more conservative approach to theorizing diaspora. Referencing the political scientist Daniel Elazar, Dufoix centers the classic notion of diaspora about the Jewish experience. (Classic, at least, in the Euro-American imagination.) In resisting any drastic changes to its self-conception and outward expression, the European Jewish community managed to carve out a place for itself in a relatively alien continent following its expulsion from Palestine. Though European Jewry by definition cultivated a distinctly European aesthetic, culture, and history, the fact that it managed to retain its Jewishness at all, and that it acknowledged that Jewishness as sourced from Palestine, defines the orthodox (no pun intended) conception of diaspora.

“To the extent that he or she works and pays taxes…which directly fund Israeli apartheid, what does resistance mean coming from a Palestinian who contributes at least indirectly to the subjugation of his or her people?”

It seems only reasonable to synthesize both scholars’ positions, if only to develop a way to talk about diaspora that isn’t dogmatic, and which can be adapted to suit whatever needs are present: The experience of diaspora focalizes the dispersal of a group from a place to which it cannot return, which results in that group’s reconstitution somewhere else. This rebirth exists along a spectrum, with one end firmly rooted in some imagined notion of home, and the other based in the realities of existing in a new and foreign space.

◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎

I exit the N on 34th Street – Herald Square. I side-step the slow and the uncertain and climb the stairs out of the subway and into Manhattan. There are only two characteristics both tourists and natives agree distinguish midtown Manhattan from other heavily photographed neighborhoods in equally large cities across the world: the shade and the smell. Of course there are cities where the skyscrapers cast longer shadows on pedestrians. (Hong Kong comes to mind.) And there are likely smellier places, too.

But nowhere else do buildings block out the sun while at the same time the street smells of nothing but urine soaked in vomit covered in a shallow membrane of bubbling sulfur. You may think I dislike the smell, but I don’t. It’s comforting to know at least one thing about New York refuses to change. I walk north towards 37th Street, and I eventually arrive at the Peoples’ Forum, where Within Our Lifetime’s event will be held.

A coffee shop and bookstore in the front, and an organizational space in the back with a stage encircled by foldout chairs, the People’s Forum is one socialist lawyer’s posthumous gift to like-minded-but-still-living comrades. A space in which to gather and conspire.

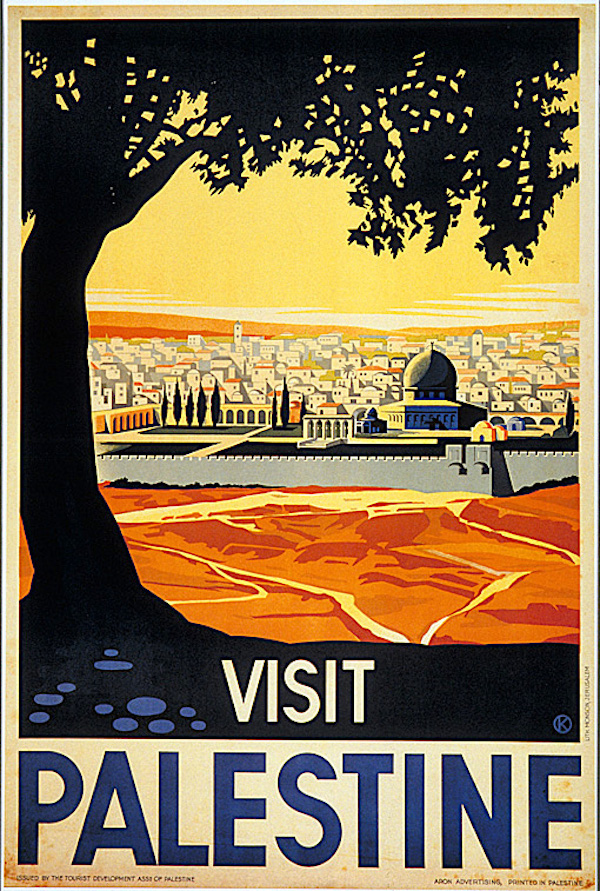

Passing the impressively large glass doors, it’s clear that, at least for today, one end of the diaspora experience exerts a far more visible influence on the People’s Forum than the other: aesthetically, very little about how the space is decorated for today’s event can be described as explicitly American. In each corner lurks a Palestinian flag, and the colors of the revolution (green, red, black, and white) are everywhere.

A painter is hanging two of his works along one wall, one conspicuously featuring Fairouz and Umm Kulthum. Pop art of Leila Khaled is on display. Two young men representing a brand called Arabian Essence stand behind a table, on top of which are clothes for sale featuring Palestinian textiles and images, from keffiyehs to maps of historic Palestine. The Dufoix-Cheyette matrix requires editing, because here we have evidence not just of a pining for a precolonial, imagined homeland. Here is a conscious vaunting of the revolution that bloomed more than a decade after Palestine’s destruction.

A revolution that has aged.

There’s something paradoxical about this. Political revolutions are supposed to be short, sudden events that occupy relatively little space in time before state and citizenry move on to a post-revolutionary phase. Ours has instead lasted for decades, and now seems to construct as much of a dreamscape for diaspora Palestinians as does a 19th century Palestine free of European Jewish colonization. At what point does a movement become a revolution? At what point does a revolution become part of a war? At what point does that war end?

I take a seat and wait for attendees to trickle in, all the while ruminating on a conversation I had with Zena Agha.

“The question of Palestine today, at this exact moment and in certain diaspora spaces where it’s possible to soberly assess resistance at a distance, isn’t a question of liberation.”

Zena is a writer, an activist, and a Harvard graduate. She’s also a U.S. Policy Fellow at Al-Shabaka, the Palestine Policy Network. On its website, Al-Shabaka describes itself as “an independent, non-partisan, and non-profit organization whose mission is to educate and foster public debate on Palestinian human rights and self-determination within the framework of international law.”

I asked Zena if she would speak with me about Palestine, and so we met in the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, where we were both writing fellows. Located in a nondescript building in Chelsea, which is surprising because nondescript is largely disallowed in Chelsea, the workshop is home to the single most impressive library of Asian-American literature I have ever seen. Adjacent to the usual clutter for which writers are often responsible, I asked Zena the question at the heart of international Palestinian activism: Will we return in our lifetime?

She looked down, and answered with the neutral tone of a person who’s more than familiar with the question he or she was just asked, “If I were to speak from a policy perspective, I would say it’s unlikely that we would return in our lifetime. But if I were to speak as an organizer and a Palestinian, I would say yes, absolutely. Partly because you need that to keep doing the work that you do. But I feel like the direction that Israel is going in implies that there will be one state for everyone. The question now is how they will [all] live.”

The question of Palestine today, at this exact moment and in certain diaspora spaces where it’s possible to soberly assess resistance at a distance, isn’t a question of liberation. It’s a question of how to contend with the only sovereign government operating within Palestinian borders. Whether or not Israel is an apartheid state was never a point of contention among those conscious of the settler-colonialism that animates its politics and punctuates its history.

The question was always what kind of apartheid state it will be. One whose racism is explicitly formalized in law? Or a variant where the racism lurks between the margins, scaffolding ignored by those who don’t want to see it? And what about the diaspora? What about those of us who aren’t direct victims of Israeli apartheid?

Zena added soberly, honestly, “If you were to look at that reality, with all the stratification, there’s only one state. And it’s currently called Israel. I think the one state they built themselves is completely unsustainable. I think within our lifetime, we will definitely see the dismantling of Israeli apartheid, and hopefully a transition to one democratic state for all people. But I don’t know if that necessarily means Palestine will be decolonized, or that we will have the right of return.”

The dismantling of Israeli apartheid doesn’t imply a resolution to the questions plaguing the diaspora. Just as importantly, it doesn’t imply freedom for Palestinians, especially if those still living in Palestine experience a final expulsion. On mundane subway rides, I like to think the Palestine Liberation Organization planned the whole thing. That they surrendered in Oslo fully aware that Israel will fail to live up to every promise it made. That it would swallow us whole, all along setting the stage for the Zionist regime to either accept its downfall, kill millions resisting said downfall, or complete its colonization of Palestine by rounding up all remaining Palestinians and tossing them out.

During the rest of our conversation, I found myself wandering into talk of land, who gets to own it, live on it, dream of it. Zena was quick to correct me, “The question is less about the land and more about the people, and I think this is something analysts get wrong when they talk about [Palestine]. They talk about the percentage of the land or the control of the land. It is a battle entirely over the land, I have no illusions about that, but I think the whole Israeli project is how do we get rid of the people? They already have all the land, for better or worse, barring Gaza. That’s where the apartheid question comes in, of separate and unequal, separate being the main thing.”

I snap out of the recollection as people begin to fill the forum, and the event formally begins.

Within Our Lifetime’s organizers take the stage to express their hopes for the evening. Here is where the other end of the diaspora spectrum reveals itself: the organizers primarily speak English. This is only practical, of course. It’s unlikely that most, if any, of the attendees understand Arabic well enough for it to be tonight’s primary means of communication. One after another the organizers reiterate familiar points.

“We intend to revitalize the revolution.”

“Tonight is about cultural resistance.”

“Dabke isn’t just a dance, it’s a form of cultural resistance.”

One organizer mentions the bombing of a Palestinian cultural center, arguing Israel intended to level a space of cultural expression. I have to quiet the voice in my head which insists that’s giving the Israelis too much credit. That it’s far more likely they didn’t care at all. That they indifferently chose a location, assuming there would be a sizable number of Palestinians there, and bombed it. Not to silence cultural resistance, because to the Israeli the Palestinian has no culture to bomb. We have been so dehumanized and drained that we aren’t even a resistance. Just a nuisance.

Following the organizers’ speeches, the spoken word poets take the stage. Much like revolution, spoken word requires something which itself requires courage: sincerity. Spoken word artists and revolutionaries are, at least in their respective performances, exceedingly, painfully, eye-wateringly sincere. Irony cannot exist in a space that needs purity of intention to function. The poets echo the rhymes, rhythms, themes, and tropes omnipresent in all of spoken word — hope, resistance, love, pain, etcetera.

Between poetry sets are performances of Palestinian dances that may have been intended as defiant, an f-you to the Israel that wants to quiet Palestinian celebration globally, but that end up seeming more than a bit awkward. The dances on show are almost exclusively associated with weddings and parties, loose environments where the point is fun and celebration. Here they’re just a performance.

“Maybe it’s only appropriate that Palestinian cultural preservation in diaspora emphasizes the celebrating of past heroes that, in our collective imagination, actually did something.”

The non-Arabs in the audience don’t know what to do, and oscillate between shameless voyeurism and shamed arm-crossing. The Arabs, myself included, clap along to the music, attempting to inject the dancing with a communal spirit that would elevate it beyond simulacra. Pining for both a precolonial Palestine full of lush olive trees and juicy oranges, and a revolutionary Palestine in tune with the project of 1960s decolonization, is on display: during one performance the dancers wear traditional Palestinian clothing, during another they wear camouflage.

From the moment I entered the People’s Forum I had to resist the urge to succumb to the indifference brought on by seeing and listening to the same visuals and platitudes that have characterized Palestinian resistance in diaspora for decades. There’s something intentional about this sort of preservation. A stillness that implies willful stasis, lack of movement, an anchor that nothing and no one can move. It’s not too dissimilar from the sort of meditation that ought to make the meditating person conscious of his or her self-presence, but which can very easily dip into abject boredom.

I realize this could very well be appropriate, as I remember that the country in which we live, the space our diaspora occupies, is a dystopia that is simply, unendingly, categorically boring. Where people die slow deaths not at the hands of a fanatical dictator suffering from acute blood lust, but because they don’t have proper access to healthcare. Where a soldier no longer sees his enemy on the battlefield before taking his life, but sits in an air-conditioned room in Las Vegas, flying a drone and killing dozens before going to McDonald’s for lunch. And so, maybe the Palestinian diaspora’s resistance in the U.S. ought to be boring, too.

Maybe it’s only appropriate that Palestinian cultural preservation in diaspora emphasizes the celebrating of past heroes that, in our collective imagination, actually did something. That it encourages the sort of rallies and demonstrations which do nothing but revitalize the spirit, and provide a place for the traumatized and the pained to commiserate in peace. Maybe that’s exactly the point of tonight — cultural memorializing as cultural resistance. And maybe in the same way that a slam poet must commit everything to his or her words, effecting the sincerity required for the form to be meaningful, diaspora Palestinians must commit their history to memory via ritual. And maybe that ritual, performed over and over again, is what makes nights like tonight so boring.

◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎◻︎

I don’t think all diaspora efforts to yield political change are toothless. Long expired members of the European Jewish diaspora are the reason mine exists at all. I think efforts by the Palestinian diaspora in the U.S. to meaningfully impact politics in 2019 are toothless. And not because its members are fearful or cowardly or weak. Quite the opposite. Diaspora Palestinians in the U.S. have to endure constant disenfranchisement and marginalization, and they handle it with a vigor and a strength that regularly borders on the superhuman.

Regardless of how critical I may seem, I firmly and unshakingly believe organizing circles like Within Our Lifetime offer a historically important resistance, just not one that’s politically compelling or one that resurrects the fire and resilience it celebrates. This political impotence is more than anything a consequence of time — there just isn’t enough of it. Because for every successful boycott, for every university that divests from Israel and Israeli companies, for every person who comes to understand the difference between Zionism and Judaism, Israel gobbles up not just more of Palestine, but more of Palestinians. Young members of the diaspora must now do more than inadvertently preserve their parents’ dialects. The most potent service groups like Within Our Lifetime can provide is the siloing of cultural memory, a resistance against erasure that has been brewing and calcifying, in that order, for the last three decades.

We’re no longer simply fighting a war over territory. This is no longer just a war over land. This is a war over people. And what are people if not their cultural heritages and memories? Their traditions and histories?

Palestinian food, dance, and clothing are now subject to Israeli theft and appropriation as readily as Palestinian land. Israel claims hummus is Israeli, even when its European founders laughed at the backward Arabs and the paste they made from chickpeas. It claims the keffiyeh is Israeli, even when the very sight of one around a young Palestinian’s neck is enough to warrant arrest and imprisonment. It claims dabke is Israeli, even though the sound of Palestinians in the West Bank beating the ground beneath their feet enrages the Israeli settlers who burn them alive and destroy their land.

This doesn’t mean hummus, the keffiyeh, or dabke are in fact Israeli, just that they now constitute a significant part of Israeli society. This portends Israel entering the global historical imagination not as an outpost of European Jewry, as its earlier architects envisioned, but as a fundamentally Middle Eastern country. Whether because of demographic changes (half of Israel’s population is Palestinian, not including the many more Palestinians living under the Israeli government’s occupation of the West Bank), or because of the European impulse to justify colonization, Israel is now attempting to transform itself into a country whose culture is rooted in the territory it occupies. What this fact may imply, what Israel wants it to imply, is Palestine’s subsumption into the larger Israeli project, whatever that may become.

What the diaspora can do, what it ought to do, is to preserve the memory of Palestine.

I already sense resistance to this last point.

“This is no longer just a war over land. This is a war over people. And what are people if not their cultural heritages and memories? Their traditions and histories?”

It seems weak and shallow, exactly the sort of sentiment diaspora communities are denigrated for holding. But I don’t think it’s weak and shallow. Honestly assessing what the Palestinian diaspora in the U.S. is, and then coming to terms with the limitations that assessment reveals, constitutes the first step towards liberation. Because in the final estimation, liberation is the ability to change the present. The only way to do that is to first acknowledge that present.

(It’s a testament to the scope of injustices visited upon my nation that even refusing to disappear is considered radical action.)

And so the diaspora must preserve, all the while continuing to boycott companies that support Israeli apartheid and occupation, encouraging divestment from institutions that support Israeli apartheid and occupation, and calling for sanctions on those political bodies that support Israeli apartheid and occupation. Not because nonviolent activism will liberate Palestine, but because despite crippling toothlessness, the only thing more defeatist than resisting nonviolently is not resisting at all.

This is the point where I lose myself in considerations too nebulous to be meaningful: What am I reacting to? Palestinian diaspora resistance in general? Palestinian diaspora resistance in the U.S. specifically? Is there much of a difference in kind between Palestinians in Chile funding their own soccer club and naming it Club Deportivo Palestino, and Palestinians in the U.S. preaching to socialists and Marxists who already agree with them regarding the need for social and restorative justice?

Or is the difference only in degree? In a global system that seems to drift ever further into the dark corners of strong-man authoritarianism, is nonviolent political action at all, in any way, truly effective? Or is the only form of meaningful resistance in diaspora, not just in the U.S. but anywhere, preservation and remembrance? In a world where activism is stymied by exceedingly powerful governments with the technology to penetrate any circle of dissidents at any time anywhere, is this all we’re capable of?

Eventually the performance will become a celebration. Literally. Within an hour or two I know the people currently seated will stand and join the performers. There’s a buffet of Middle Eastern foods and deserts lining the wall, and those in attendance will eat and drink and be merry with one another soon enough. I know this, and yet I don’t care to celebrate. More importantly, I don’t want to get in the way of people celebrating. Because if this is all the diaspora has, it might as well enjoy it. And so, as another round of dancing begins, I get up as discreetly as possible, I exit the People’s Forum, and I head back in the direction from which I came.

You may also be interested to read these stories: