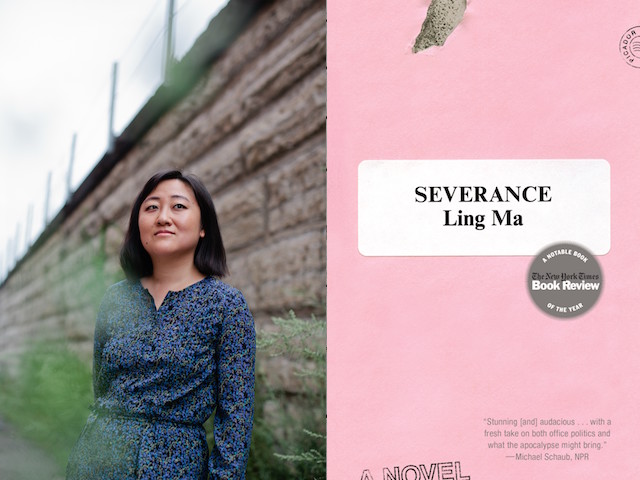

The author of Severance talks apocalyptic immigrant narratives, co-opting consumerism, and the disease of remembering.

May 9, 2019

In Severance, Ling Ma’s debut novel, a pandemic renders those who contract Shen Fever fated to unconsciously repeat old routines—memory and motivation are the thin lines that separate the fevered from the unfevered. Candace Chen, a first-generation Chinese American living in New York whose connection to home and family is nebulous at best, is seemingly immune to the disease. Candace continues to work her job as the production coordinator for a publisher of English-language Bibles while she documents the disaster through her photo blog, NY Ghost. When external circumstances force her to leave, she encounters a small group of fellow survivors led by Bob, a former IT specialist who attempts to enact his own small bureaucracy among the only human beings left to care.

Through Candace’s lens, Severance explores what it means to find comfort and meaning in daily habits. In Ling Ma’s short story “Los Angeles,” published in Granta in 2015, the unnamed narrator meets her husband on a dating website called LoweredExpectations.com. In the description of what she’s looking for in a partnership, the narrator writes, “I want to know someone for longer than a few years […] I also want not to flee. By that I mean I want constancy. I want to be constant.”

It’s a sentiment that Candace shares throughout Severance. While she remembers the childhood routine she kept with her mother in Fuzhou, before her family’s immigration to the United States, Candace attributes her sense of serenity to her mother: “It had to do with the way she managed our days, so steady and constant and regulated. I have looked for that constancy everywhere.” Dedication to routine, the adherence to small acts, provides an emotional lifeline to her parents and a way of committing herself to their memory when they are no longer around.

What Severance does best is capture the sense of being caught between two worlds, the dissociative feeling of loneliness and alienation that accompanies life as a capitalist drone, as a post-apocalyptic survivor, or as the only daughter of Chinese immigrants. It’s a feeling that the novel’s characters attempt to cover over, to varying degrees, with a mixture of materialism and rote efficiency. In a section about Candace’s parents, written deftly in close third-person, the narrator notes, “[Her mother’s] homesickness eased in department stores, supermarkets, wholesale clubs, superstores, places of unparalleled abundance. The solution was shopping, [her father] observed. He was not trying to be reductive.” Accumulation offers a new identity, a palliative sense of home.

A bulk of the narrative takes place within a shopping mall. Pioneered by architect Victor Gruen in the early 1950s, the American shopping mall was originally designed to be a utopic hub of public space, a way of bringing urban density and variety to suburban sprawl. Gruen envisioned the mall as the centerpiece of a built environment that would include housing complexes, schools, parks, medical centers and social services. In a scene between Bob and Candace that takes place inside a repurposed L’Occitane, Bob reminisces about the time he spent at the mall as a teenager, wandering through arcades, away from his unhappy home. The moment seems to suggest that what can seem tacky, meaningless, or passé (department stores, a shopping mall) can continue to hold personal significance to those who inhabit it, even if a memory is the only trace that remains.

Like the legacy of the American shopping mall, Severance posits a thorny and complicated relationship to work, consumerism, power, and identity. The main question of the novel seems to be, Who and what do we grasp onto when confronted with the loss of home or the threat of real social, political and ecological disaster? When all the customary markers of identity are erased, what sense of self is there left to save? At a crucial turning point in the story, Candace receives a visit from her mother who urges her to exercise, brush her teeth, and pull herself together in order to leave her current situation. It’s a return to old habits, the sort of routine we chafe against, but in this case Candace’s very survival depends on it.

Severance won the 2018 Kirkus Prize for fiction and will be released in paperback on May 7th.

Jen Lue

I’ve read that Severance started out as a short story. At what point did you think you had a novel on your hands?

Ling Ma

I think I had the idea it was a novel once I started writing about the Bible manufacture process, when Candace speaks to the production editor at the religious publisher about the Gemstone Bible and the labor issues in China. So this would have been in the first chapter. I started getting more ideas, like setting a scene at a printer in Shenzhen. Once we moved from the world of the collective first person to the world of the individual first person, when we went through a day in Candace’s life, I realized there was a lot more to unpack.

JL

I like that Candace slowly emerges as a subversive element after she is forced to leave New York and join Bob’s group. There are key moments in the journey to the Facility where she deviates from Bob’s rules, causing tension within the group. Did you know where and how Candace would end up when you started?

LM

I always knew tensions would arise between Candace and Bob, and that Candace would avoid any confrontation until she was forced to act. She thinks she can compartmentalize herself and not really show her hand. I thought of this band of survivors as a roving office in some ways. They don’t know each other very well, and they may not naturally click as personalities, yet they’re forced to spend a lot of time together, working on their various task assignments. Bob is the boss because he decides to be. It doesn’t take a lot to make a group of people bend to your will.

JL

Shen Fever is described as a “disease of remembering” and the fevered become creatures of habit, destined to unconsciously mimic old routines. As I was re-reading the book, I was struck by how, by removing the particulars of motivation and context, the fevered also seem immune to the sort of memory that the survivors are subject to. The illness seems to sever those who contract it from the trappings of a unique self or identity (ties to a specific place, family, history, etc.).

When considering whether or not she would ever visit Salt Lake City again, the city where her parents first immigrated, Candace thinks, “The past is a black hole, cut into the present day like a wound, and if you come too close, you can get sucked in. You have to keep moving.” Despite her statement, I get the sense that something a little more complicated is going on.

How would you describe Candace’s relationship to memory and the past?

LM

As for Candace, some readers have observed that she doesn’t really have a home, and therefore seems immune to becoming fevered. Despite her assertion that “You have to keep moving,” it’s so clear to me, in those scenes set in Fuzhou, that she feels a tenderness towards the city, her family there. Even having lived there for only a few years, that home-nostalgia is a feeling that she doesn’t even know she carries around.

I did wonder, what does it mean for Candace to go home? China is a country that has changed so rapidly since the 80s. During that time, Deng Xiaoping first established “special economic zones” in places like Shenzhen and Fuzhou, effectively opening up the country to free market. Candace grew up in China in the 80s, and immigrated to the US as a young kid. Since the time she would have been away, China had undergone drastic development in its economic boom. The cities are much more developed, much more westernized too. In many ways, the Fuzhou she grew up in is gone.

JL

I love the role that photography and Candace’s blog, NY Ghost plays in the book. Can you speak a little bit more about NY Ghost and the influence that photographers like Nan Goldin, Vivian Maier, and William Eggleston may have had on the work?

LM

Some of those were just some personal favorites. I just love the photographs of Nan Goldin. I remember wandering into a bookstore during my first weekend of college, randomly opening up The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, and just being startled by those images. And I love the idea of Vivian Maier as a nanny, taking walks with her charges through Chicago. Someone who is on the margins, who has no real power in society, who observes everything on the ground level. I remember going to the Vivian Maier exhibit after work at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2011, when she first came to public attention. The images had such a specific point of view.

JL

One of the most striking parts of the novel for me is Chapter 16, which starts with Brigham Young and the Mormon migration, in third-person omniscient point of view, and shifts into the close third perspectives of both Ruifang and Zhigang, Candace’s mother and father. Can you speak a little more about how this particular chapter came to be a part of the book?

LM

As the apocalypse happens all around Candace, she keeps working. So the inevitable question is, why does Candace keep going into the office? There are a number of answers to this, but one certainly has to do with that immigrant pressure to strive, something that is instilled in you if you grow up in an immigrant household. Throughout the novel, these memories of her family and life in China kept seeping in. So I knew the novel would eventually dovetail deeper into Candace’s background.

Yet when it came time to write that background chapter, which I believe is Chapter 16, it was pretty tough to begin. The whole novel is narrated in the first person, from Candace’s viewpoint, but no one speaks deeply about themselves on cue. I couldn’t seem to write this chapter in the first person, so I began almost as an omniscient third-person narrator—or, more accurately, the omniscient first-person narrator, which is a strange perspective. Eventually, over the course of the chapter, Candace’s presence and voice becomes more apparent.

JL

As a chapter, it’s pretty wild, structurally and differs a lot from the rest of the book. Did you get any comments from your editor on it? How was the editorial working process in general?

LM

In the early drafts, that chapter was a bit shorter and more curtailed. Maybe I felt self-conscious about how that chapter diverges from the rest of the novel. My editor mentioned that I should go further with it, that it needed more. She was tapping into my instincts, which is a sign of a good editor. I could feel that too, so I just let that chapter unfurl as much as it wanted and take up more space. From what I can remember, we didn’t change too much of the chapter after that.

JL

There are several scenes of tenderness that occur within the larger consumer system: Candace burning paper cutouts for her parents in the afterlife, Bob’s nostalgia for his hometown shopping mall. Was it your intention to depict a more nuanced relationship to objects and consumption alongside the satire and critique?

LM

The novel tries to show how consumerism permeates our psyches. In particular, I was interested in how certain Western brands are culturally metabolized by consumers in China or other parts of Asia. Or maybe not brands, but even certain cultural figures. It’s ridiculous that Arnold Palmer, an American golfer born in 1929, has a trendy Hong Kong handbag and accessories line for women. It doesn’t make any sense!

Clinique gets mentioned a lot in the novel. During the 80s and 90s, it was like this unattainable, supremely aspirational brand. And now today, as income levels have shifted during China’s economic boom, it’s maybe considered second-tier skincare compared to brands like Dior or something. I am not an expert in any of this, just an observer.

I’ve been watching this Japanese reality show Terrace House, and one source of fascination is how this group of young Japanese people curate their image through American brands like Vans and Patagonia. I love looking at what they wear.

JL

In an interview for the Chicago Tribune you spoke about the pressures of writing a traditional immigrant novel and resentment for the expectation that, as writers of color, we are asked to explain our otherness, to make it palatable. I wonder if you’ve encountered any work that deals with Chinese American identity in a way that’s been influential to your own process.

LM

There were some inaccuracies in that article, but my feelings about the immigrant narrative are something I’m still processing. It’s a personal hangup. For a long time (basically, in the 90s when I was coming of age), the immigrant narrative seemed like the predominant story being told about Asian Americans. These stories definitely have their place, but as a teen living in Kansas, as someone who was always asked “Where do you come from?”, I was annoyed that every narrative featuring an Asian American protagonist came with some origin story, acquiescing to that question we always got asked. (And, I should stress that I wasn’t the most widely read person growing up, so there may have been more out there than I realized.)

In grad school, when a faculty member told me to write about “where you come from,” that was my worst nightmare. Though Severance does contain an immigrant narrative, it was something I initially resisted—and of course, it had to be wrapped up in an apocalyptic conceit. You could argue that the immigrant narrative and the apocalyptic narrative are similar in that they’re both traditionally organized around a Before and an After.

There’s been this profusion of Asian American lit recently. I read Jenny Zhang’s Sour Heart, and she got so much of Chinese American girlhood right that I was reminded of things that I hadn’t thought about in a long time. I can’t remember experiencing that kind of reflection before.

JL

Are there any works by non-Chinese American writers and artists that you’ve resonated with for different reasons?

LM

For prose style, I tend to take my cues from certain Midwestern writers: Willa Cather’s My Antonia, William Maxwell’s So Long See You Tomorrow, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. Their work has this kind of plainspoken lyricism, which I associate with a very Midwestern sensibility. The writing can be beautiful without being ostentatious. I think it’s also my parents’ aesthetic, how I grew up.

Television and movies influence me a lot. I’ve mentioned Mad Men so often that I need to stop, but it really did illustrate new ways of structuring for me. It’s not a perfect show, but the storylines layered, deepened, and dialogued with each other so well. It was also very savvy about incorporating certain heritage brands—like Chevy, Hilton, Playboy, Coca-Cola—and using our associations of those brands to deepen its ideas.

It’s helpful to look at other storytelling mediums beyond literature, so you don’t get locked into the conventions of the form. Literary fiction is full of tropes like any other genre.

JL

Throughout the novel, Candace navigates a complicated and often ambivalent relationship to routine. Do you subscribe to any routines in your own writing process?

LM

When I wrote Severance, I was aware that I didn’t know how to write a novel, having never successfully completed one before. So I adhered to the routine I was most familiar with, which is the office schedule. I worked from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., roughly. This was during the summers when I was in grad school. And then, at night, my partner and I would binge several hours of television, thinking about narrative structure, thematic layering. In retrospect, that routine was a way of mesmerizing myself deeper into the novel. The routine made everything possible, all the ideas that came. It got pretty unhealthy though.

JL

I was really struck, while reading the book, by how deftly you wrote about the presence of Christianity in certain Chinese American communities. It’s something I’m familiar with from my own childhood but I’ve rarely seen written about anywhere else. How did you decide to include it as a plot point in the novel?

LM

I was simply trying to connect low-wage Bible manufacture in China with the role of Christianity in immigrant communities as part of the cultural-assimilation process. Maybe “connect” is an overstatement, but I wanted to make sure these two things were included in the same narrative, to set them within proximity to each other and allow the reader draw the connections. And I agree with you that we don’t really see that much about the role of religion among Asian immigrants. Going to church was a big part of my childhood. I remember Sunday school followed by Chinese lessons in the same church basement. These could well be the memories of many other Asian Americans. It could be a whole other book. Someone should write it.