The legacy of an intellectual friendship in an age of Islamophobia—on the 10-year anniversary of Said’s death.

September 26, 2013

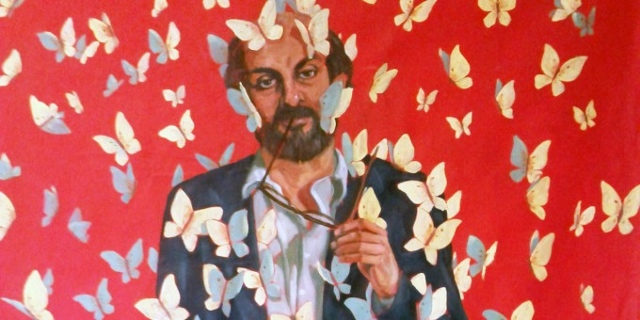

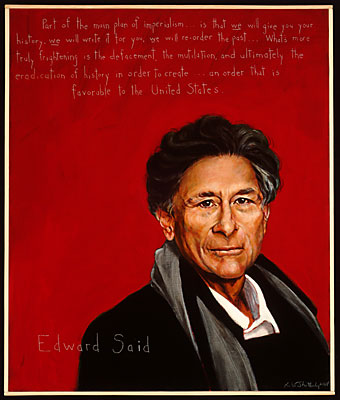

This past April, in an op-ed for the New York Times, Salman Rushdie pondered over the ways in which public respect for moral courage has diminished, noting how strange it is that we have become increasingly “suspicious of those who take a stand against the abuses of power or dogma.” Rushdie provided several examples of moral courage, ranging from South African activist Nelson Mandela, to Saudi poet Hamza Kashgari, to the Russian band Pussy Riot. The one that caught my eye was the late cultural critic and scholar of comparative literature, Edward Said (1935-2003). Rushdie, in the op-ed, described Said as an “out of step intellectual,” noting that he was “dismissed, absurdly, as an apologist for Palestinian terrorism.” Said had been one of Rushdie’s greatest admirers, and was particularly enamored of the way Rushdie wove the complexity of cultural differences into his early literature, essays and critiques. One wonders what route the friendship between Said and Rushdie would have taken, since such complexity no longer informs Rushdie’s political stances.

*

A quarter of a century ago, which from today’s perspective appears to have been a more innocent time—before 9/11 and the War on Terror, before the Iraq War and the US invasion of Afghanistan, and even before the first Gulf War and Ayatollah Khomeini’s infamous fatwa—Salman Rushdie and Edward Said sat down to speak about exile and literature. Their intellectual and personal friendship is evident in that 1986 interview, which took place at the PEN Congress in New York, and was published in the New Left Review shortly thereafter. The interview was also later published in Rushdie’s book of essays, Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981-1991.

The conversation ranged from American and Israeli perceptions of Palestinian people and Said’s alienation in New York, to Palestinian identity and consciousness, woven throughout with reflections about Rushdie’s novel, Midnight’s Children and Said’s book, After the Last Sky, co-authored with Jean Mohr. Rushdie noted:

In Edward’s view, the broken or discontinuous nature of Palestinian experience entails that classic rules about form or structure cannot be true to that experience; rather, it is necessary to work through a kind of chaos or unstable form that will accurately express its essential instability. Edward then proceeds to introduce the theme…that the history of Palestine has turned the insider (the Palestinian Arab) into the outsider.

It was clear that Said and Rushdie shared an affinity over their shared experiences of displacement and multiple forms of non-belonging.

What Said found particularly appealing about Rushdie’s writing were the innovative strategies of hybridity, multiplicity, irony, and language-play that Rushdie employed in literature—especially as it was connected to imperialism, exile, and boundary-crossing. He told Rushdie, “It is almost impossible to imagine a single narrative (of the Palestinian experience): it would have to be the kind of crazy history that comes out in Midnight’s Children, with all those little strands coming and going in and out.”

Both Said and Rushdie were also robust voices of dissent during the 1980s. In his book, Culture and Imperialism, Said lauded Rushdie’s moral courage in singling him out as one of the few writers in the UK critical of the Falklands War: “In 1984, well before The Satanic Verses appeared, Salman Rushdie diagnosed the spate of films and articles about the British Raj… Rushdie noted that the nostalgia pressed into service by these affectionate recollections of British rule in India coincided with the Falkands War…” In that passage, Said also defended Rushdie against critics who “seemed to disregard his principal point”—that popular representations of the past—of formerly colonized peoples by their former colonizers—were being used to breathe new life into new imperialist goals.

When the dangerously unconscionable fatwa was launched against Rushdie, Said spoke out passionately in his friend’s defense, calling Rushdie, “the intifada of the imagination,” iterating that it was the secular intellectual’s responsibility to defend him, for “freedom of expression cannot be sought invidiously in one territory, and ignored in another.” “Rushdie,” he said, “is everyone who dares to speak out against power, to say that we are entitled to think and express forbidden thoughts, to argue for democracy and freedom of opinion.”

*

Five years before the 9/11 attacks, Said penned a new introduction to the second edition of his 1981 book, Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World. Said’s contention was that the perception of Islam in the US was undergoing “a strange revival of canonical, though previously discredited, Orientalist ideas about Muslim, generally non-white, people—ideas that have achieved a startling prominence at a time when racial and religious mis-representations of every other cultural group are no longer circulated with such impunity.” Said’s book anticipated some of the more recent historically situated critiques—such as those by Stephen Sheehi and Deepa Kumar —of anti-Muslim racism or Islamophobia, in its current avatar: as handmaiden to the US-led war on terror.

Public critiques of Islamophobia, as was the case prior to 9/11, simply do not have the kind of caché as do stringent critiques of Islamic radicalism. In Covering Islam, Said writes that the corps of ‘experts’ on Muslim peoples “brought out to pontificate on formulaic ideas about Islam” in the media during crisis moments, which he noted had grown to prominence in the mid-1990s, have mushroomed in the post 9/11 world.

Many of the formulaic ideas about Islam that Said had critiqued in his books, Orientalism, as well as Covering Islam, also form the backbone of Islamophobia. Islamophobia relies upon false, oppositional binaries, superlatives, and monoliths. It is “they”, Muslims, who are said to be inherently more violent, belligerent, intolerant, primitive, and un-free; it is “they” who are said to refuse full adoption into modernity; it is “they” who are particularly oppressive towards women; it is “they” who need a reformation; and so on.

Today, in spite of the rise of extremist right-wing radicalism within the US, overwhelming media attention has been restricted to seeing terror as a peculiarly Muslim phenomenon, with Muslim being defined as some racialized other. This is why the Boston bombing was considered to be a national tragedy preoccupying the news cycle for weeks, but the attack against Sikh worshippers leaving six dead, over a year ago, was hardly the focus of similar attention. Nor are anti-Sikh hate crimes limited to neo-Nazi gunmen in Midwestern US: this past Saturday, a professor from Columbia University was attacked by a New York city mob. So racially coded are perceptions of Muslims that several Americans demanded that the July issue of Rolling Stone featuring Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on the cover be taken off newsstands. CVS and Walgreens gave in to the calls for censorship, and decided not to sell the magazine in their stores: people seemed to be offended that that a ‘terrorist’ could be White. So synonymous have the words Islam, terrorism, and Muslims become, that one has to repeatedly provide correctives—as Glenn Greenwald did on Bill Maher’s show—to the view that Islam is uniquely preoccupied with violence and intolerance.

The media cacophony and ceaseless rounds of war propaganda have made it difficult for critiques of Islamophobia to be widely heard. Since the onset of this unending war on terror, for public intellectuals in the US to assert that war is terror by another name while criticizing Islamophobia is often perceived as an unwarranted disengagement from condemnations of terrorism. Some have earned the charge of being apologists for “Islamic terrorism” or “Islamism”—a word, Rushdie had noted in his 2001 op-ed, that “we must get used to.”

Condemning Islamophobia requires the kind of ‘moral courage’ to which Rushdie referred. Rushdie stated in his Times op-ed that “it ought still to be possible to recognize the courage it takes to stand up and bellow them [critiques of America] into the face of American power,” adding as an aside, “One may not be pro-Palestinian, but one should be able to see that Mr. Said stood up against Yasir Arafat as eloquently as he criticized the United States.”

And yet, in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, Rushdie himself ventriloquized commonly held assumptions and myths about Islam in the US. Opining in the New York Times that, “Yes, this is about Islam,” Rushdie elaborated: “if terrorism is to be defeated, the world of Islam must take on board the secularist-humanist principles on which the modern is based.” Rushdie also diagnosed millions in this familiar litany:

For a vast number of “believing” Muslim men, “Islam” stands, in a jumbled, half-examined way, not only for the fear of God — the fear more than the love, one suspects — but also for a cluster of customs, opinions and prejudices that include their dietary practices; the sequestration or near-sequestration of “their” women; the sermons delivered by their mullahs of choice; a loathing of modern society in general, riddled as it is with music, godlessness and sex; and a more particularized loathing (and fear) of the prospect that their own immediate surroundings could be taken over — “Westoxicated” — by the liberal Western-style way of life.

As Said had long argued, this un-nuanced view of the world, in which “all Muslim societies” are said to lack, or “loathe” the modern world, is hardly new. For many decades now, a popular, mythological framework masquerading as common sense has preoccupied European and American discussions of Muslims and Islam. According to its facile premise, the world is made up of divisions between Western liberalism and Islam, civilization and the barbarians, progress and primitivism, the modern and the traditional, rationality and religion, liberated Western women and their oppressed Muslim sisters.

Historical, political, and cultural realities are actually quite messy, and do not fit into neat little boxes of either/or, the West and the Rest, or the West and Islam. In 2001, while Rushdie distanced himself from the paleolithic musings of Samuel Huntington’s clash of civilizations, his public writings also served to refine the anti-Muslim hysteria which was preoccupying the public discourse in Europe and the US. Those who have studied formerly colonized, modern societies where Muslims constitute either majority or minority populations have been at pains to show that such a simplistic perception of the world is deeply flawed. This point is worth considering especially in light of a question Rushdie asked over a decade ago, a question which continues to rear itself repeatedly: “Suppose we say that the ills of our societies are not primarily America’s fault, that we are to blame for our own failings?” Rushdie’s question forced a false choice: blame lies either with the US or with Muslim societies.

*

This sadly binary view of the world is at odds with Rushdie’s celebration of mélange, hodge-podge, and multiplicity. If we return to Rushdie’s earlier experiments with language, and his essays about culture and exile, one hears a more politically engaged and intellectually sensitive voice, such as in his collection of essays, Imaginary Homelands, where Rushdie dwelt on issues of xenophobia in the diverse societies of the UK. For Said, Rushdie’s most significant contribution had to do with how a writer inhabiting the liminal spaces—the spaces between cultural worlds—necessarily demands a double critique when one speaks truth to power: whether that might mean a critique of powerful self-appointed spokespersons of a purist Islamic (or Hindu, or Christian, or secularist) morality who prohibit freedom of speech, or towards those who, under the guise of secular humanism, defend the notion of liberating peoples at gunpoint.

Yet, such notions of complexity and hybridity no longer inform Rushdie’s political stances. Like many public intellectuals who were confidently asserting all sorts of things about Islam in the build-up to the war on terror, Rushdie ignored the complex historical and political encounters between Western and Muslim peoples in his non-fiction writings. These encounters were, of course varied, such as in the 16th century, with the Mediterranean travels of Moroccan born al-Hasan al Wazzan (Leo Africanus), or the Jesuits in the court of India’s Mughal emperor Akbar.

Rushdie’s politics have shifted over the past two decades. Today, his voice is a far cry from dissent. It is now characterized by conformity to neoliberal political ideals and views of Islam, combined with the self-indulgence that comes with celebrity status. Summoned repeatedly as a token representative of the third world condition for Western audiences, Rushdie has used his platform to generalize from his particular individual experience issuing from The Satanic Verses controversy, across a wide spectrum of peoples. In this sense, Rushdie is very different from the late Edward Said, who said he instinctively found himself on the other side of power.

In 2003, Said himself raised the issue of Rushdie’s political transformation, towards the end of a talk at Columbia University. The bulk of the talk was focused on Rushdie’s writings, and Said had described his prose as “verbal fireworks.” Said mentioned that Rushdie’s years of living underground had affected the writer deeply: “He felt confusion, denial and anger for the onslaught against [The Satanic Verses]. There was a sense his own people turned against him.” Sensitively, Said added that because Rushdie was so embattled, “he was not as aware as he could have been of the many people in the Muslim world who defended him and in fact, spoke out.” Said also told the audience that Rushdie’s political views have “changed over time,” referring, amongst other things, to Rushdie’s view on the impending war with Iraq, which Rushdie supported. Said added, “There’s a greater disconnect between his non-fictional prose and his fiction, now, than there was in the decade of the 1980s.” Rushdie did not speak out against the war, nor did he lend intellectual support to the millions around the world who protested against the US invasion of Iraq—a war which left behind multi-headed hydra of devastation.

That was in 2003, ten years ago, the same year that Edward Said passed away.

In the decade since, Rushdie has dismissed the term “Islamophobia,” in what are, within the US, the most Islamophobic times to date. He signed off on a manifesto that claimed Islamophobia is “an unfortunate concept which confuses criticism of Islam as a religion with stigmatization of its believers.” The manifesto was written in response to the Danish cartoon controversy of 2005 which had sparked protests amongst Muslims in various parts of the world. Rushdie defended the right of the paper to publish the racist cartoons, for indeed the newspaper did have the right to publish what it so willed. (Largely absent from the entire controversy was the point that depictions of the Prophet had long been a part of the history of Islam, from Indo-Persianate paintings to Ottoman art, to contemporary Iranian images). But, was it really a matter of moral courage for Rushdie to defend racist cartoons while displacing critiques of Islamophobia? Recall Rushdie’s critique in the early 1980s about how nostalgia for the British Raj coincided with the Falklands war. By 2005, Rushdie is seemingly uninterested in such contextual critiques, say, how the literal and figurative depictions of Muhammad by the Danish cartoonists serve a political and cultural purpose at a time when anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe is on the rise.

Given his writings about the perceptions of Islam, Said would not have crassly reduced the real phenomenon of Islamophobia to a vague and confusing concept. Said might have even pushed Rushdie to consider his new political stances, and would likely have raised questions about Rushdie’s selective humanism.

After all, Islamophobia is not some confusing concept. Nor is Islamophobia simply limited to the hate-crimes against minorities—both Muslims and those mistakenly perceived to be Muslim—which have seen a dramatic rise in the past decade. Nor is the fear and prejudice against Muslims restricted to the radical right: Pam Geller and Robert Spencer of the anti-Muslim group Stop Islamization of America represent the obscene tip of the iceberg, of what is actually a very widespread, disturbing trend of anti-Muslim racism.

*

Islamophobia today is deeply imbricated in US policy and has led to a virtually separate criminal justice system for Muslims. It justifies the constant surveillance of immigrant communities, the profiling of Muslims in places like streets, mosques, universities and the monitoring of Muslims’ charitable giving; it validates spying on Muslims and the erasure of their civil rights and for them to be detained without being charged with a crime; it also espouses their torture—and not only by state officials, but in propaganda films that are honored at the Oscars; it is used as the script by which the FBI entrap ‘dark-skinned’ men and proclaim foiled terror plots; and of course, it pervades everyday life, not only from Islam bashing metro advertisements, but the discrimination and harassment of Muslims in schools, work places, and other public spaces. Islamophobia means the most vulnerable of Muslim minorities living in Europe and the US—working class immigrants—have borne the brunt of the siege on civil liberties. What psychological impact such a siege is having upon these communities is not altogether clear, since the few resources such minorities do have are mostly being directed against external assaults to their freedoms, instead of the internal problems within their communities.

Ultimately, Islamophobia thrives on the notion that any terroristic attack—whether actual or potential—brings to mind, “Yes, this is about Islam.” Given this state of affairs, one wonders: where was Rushdie’s moral courage ten years ago? When it comes to the widespread anti-Muslim racism known as Islamophobia—one that has been employed repeatedly as justification for the national security state aims of US imperial aggression—Rushdie’s is a withering moral courage.