From tender coming-of-age and coming-out stories to eye-opening historical fiction & unforgettable fantasy

October 26, 2020

For our monthly Bookmarks series, this October we asked seven YA fiction writers with new or recently published books to recommend two works of Young Adult fiction that have been important to them, both as writers and readers. We wanted to know, what YA literature has shaped the way these writers tell stories? What books have demonstrated to them what is possible in the genre? Read what they shared with us!

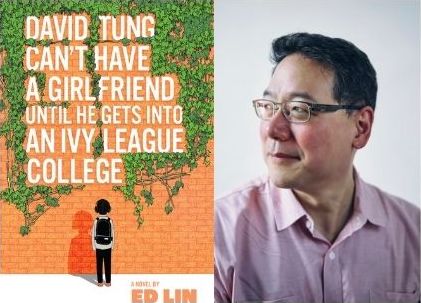

Ed Lin

Publishing this week from Kaya Press, Ed Lin’s YA-debut David Tung Can’t Have a Girlfriend Until He Gets Into an Ivy League College explores coming-of-age in the Asian diaspora while navigating relationships through race, class, young love, and the confusing expectations of immigrant parental pressure. “A fast-paced, acid-tongued, hilarious teen drama for our age” (Marie Myung-Ok Lee). We asked Ed what books shaped his love of YA.

Chernowitz! by Fran Arrick (Berkley Books, 1981)

In my adult life, I’ve woken up a few times with an overpowering memory of something from my childhood. Something clear and sharp like pieces of a windowpane that my head just crashed through.

One of those suddenly-with-me recollections is reading Chernowitz! in seventh grade. It’s the story about Bobby Cherno, a Jewish American kid who encounters anti-Semitic bullying in his first year in high school. The bully, a big kid on the wrestling team, taunts Bobby, calling him “CK,” short for “Christ-killer,” and adds the “-witz” to Bobby’s last name. Even worse than the bullying is that Bobby’s old friends side with the bully when he’s around. In private, they act like they’re Bobby’s pals.

I remember reading Chernowitz! quickly, driven by the anger I felt at what Bobby endures, and how similar it was to my own experience with racism.I was surprised when our seventh-grade librarian, who was fantastic at giving readings, chose to read parts of Chernowitz! Hearing her read out loud what had been a private comfort for me made me feel like she was telling my story.

Rolling the R’s by R. Zamora Linmark (Kaya Press, 1995)

Nothing’s better than a book about kids living in Honolulu in the Farrah Fawcett Fan Club telling their stories in pidgin through letters, poems, and other detritus torn from their notebooks. Who’s having sex with whom? It’s the 70’s. Everyone is, and even the school janitor gets some play.

There’s the hot mix of Asians, sexualities, and shifting and shifty narrators. No one seems to have money, and everyone’s hustling to get something. Rolling the R’s is beyond coming-of-age and coming-out stories. Even if you put it in a box and seal it in a plastic Ziplock bag, the smell will still get out. I would have been freaked out if I had read this in high school, and our district in Jersey probably would have lost government funding if this was in the library. I mean that in a good way! A quarter of a century later, Rolling the R’s keeps rolling on past all barriers.

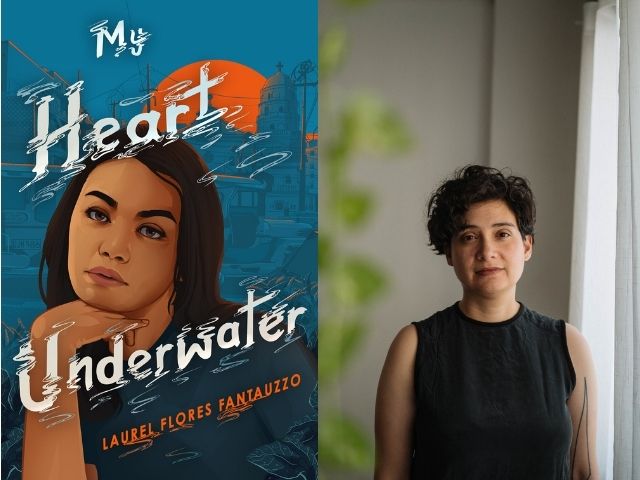

Laurel Flores Fantauzzo

A coming-of-age debut about a Filipina American teen drowning under pressure and learning to trust her heart, Laurel Hantauzzo‘s My Heart Underwater is out this month from Quill Tree Books. “[A] lovely, magnificent wonder of a novel that will leave you with the rarest of tender heartaches… You won’t walk freely, or willingly, from these pages.” (Marjorie Liu). Read Laurel’s recommendations:

American Son by Brian Ascalon Roley (W. W. Norton & Company, 2001)

We each have an origin book that resonates; a bell we hear for the first time, ringing out that literature recognizes you, finally. I had never read characters with a white father and a Filipina mother, or a narrative that recognized the threat and isolation I felt outside Los Angeles.

In 1993, teenager Gabe lives in the shadow of his older brother, Tomas, who fashions himself as a Mexican-American outlaw training attack dogs. Their mother has rejected the Philippines and its culture, and suffers racism in LA. Their uncle wants the boys to live in the Philippines under his authoritarian fist. The scenes and gestures of the book will live in me for the rest of my life—Gabe’s recognition of Tomas’ vulnerability. Tomas stepping on Gabe’s face. Gabe’s bizarre encounter with a white truck driver. And Gabe’s betrayal of his mother.

As I’ve grown older, my questions have deepened—did Ika reject the Philippines out of some unstated trauma? How did Gabe interpret his own performance of gender? And—what if he had been sent to the Philippines? The final question animated my own YA novel, which does send an anxiety-wrecked, queer FilAm to Metro Manila. Ascalon Roley led the way 20 years ago, and for that I am forever grateful.

When the Rainbow Goddess Wept by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard (University of Michigan Press, 1999)

One day my lola made a sharp zipping sound with her lips and tongue, and sliced her pointer finger down. I realized she was evoking bombs lacerating the air. The sounds of Japanese and American destruction in the Philippines were still so vivid in her mind, decades later in California. These were historical memories I had never seen depicted in fiction, until Manguerra Brainard’s 1994 novel. Nine-year-old Yvonne Macaraig lives in a happy family in Cebu, until the invasion by Japanese forces during World War Two. Her father is an engineer who suffers from a brutal capture, and Yvonne witnesses the unspeakable losses her neighbors endure. Throughout the 1941 to 1943 years of occupation, Yvonne is buoyed by reminders of supernatural Philippine beings and powers. Laydan, a domestic worker essential to the family, cooks their meals, and shares oral histories of folklore and survival, helping her to thrive.

My mom handed me the book when I was a year older than the narrator. When the Rainbow Goddess Wept was a first lesson of the humanity and rescue inherent in stories. The narrator in my own YA novel is traumatized in more subtle ways, but as Yvonne’s relationships carried her, so too is my narrator restored by family and friendships. Brainard first taught me how to depict a young Pinay, and gave me the courage to add another to readers’ shelves.

Adiba Jaigirdar

Bangladeshi Irish teen Nishat doesn’t want to lose her family, but she also doesn’t want to hide who she is, and it only gets harder once a childhood friend walks back into her life. In The Henna Wars, out this May from Page Street Kids, Adiba Jaygirdar “seamlessly weaves issues of racism and homophobia into a fast-moving plot peopled with richly drawn characters” (Kirkus). Adiba tells her about some of her favorite recent YA novels:

From Twinkle, With Love by Sandhya Menon (Simon Pulse, 2019)

I know that When Dimple Met Rishi is everyone’s go-to Sandhya Menon book, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t fall head-over-heels in love with From Twinkle, With Love, her standalone sophomore novel. There’s so much about it to love, but what I adore is that Twinkle Mehra is so… messy. She makes so many mistakes. She does so many things that she absolutely should not do. She hurts people and she makes things complicated for herself. And in the end she has to try and dig herself out of the huge mess she’s made. We don’t often get to see brown girls like that. We don’t get to see brown girls who are so messy, who make so many mistakes, and who are given the chance to make up for all of it, and still get their happy ending.

I definitely thought a lot about Twinkle as I wrote both The Henna Wars and Hani and Ishu’s Guide to Fake Dating, because the brown girls in my books are far from perfect, and characters like Twinkle remind me that they don’t have to be anywhere close to perfect. Brown girls get to be complicated and messy, too, and I’m allowed to write their complicated and messy lives!

Love From A to Z by S.K. Ali (Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for You, 2019)

If I could choose one book to give to my younger self, it would be Love From A To Z—it is such an important book for even my adult self to read. Reading this book was like seeing a reflection of myself, especially in the character of Zayneb, who I think is reflective of a lot of young women of color who are very frustrated at a world that so often doesn’t seem to care about us. Zayneb fights for injustice, while also making mistakes and mishandling her emotions, but she also gets to have happiness and support and to fall in love. It’s definitely a book I think a lot about when I write my own romances, because I want to write books exactly like this. Books that are unafraid to be honest about the reality that we live in, while also giving us joy.

Traci Chee

A 2020 National Book Award finalist, We Are Not Free is the collective account of a tight-knit group of young Nisei, second-generation Japanese American citizens, whose lives are irrevocably changed by the mass U.S. incarcerations of World War II. “Chee’s nuanced and unforgettable characters will serve to enlighten readers about this devastating and shameful piece of America’s past” (Veera Hiranandani).

Under a Painted Sky by Stacey Lee (Speak, 2016)

Set during the California Gold Rush, Under a Painted Sky stars Samantha, a Chinese American girl fleeing Missouri on a murder charge. As her escape takes her westward, she ends up on the Oregon Trail with a runaway enslaved girl and a group of young cowboys. Although I’d studied this era in school, reading this book was eye-opening for me. So much of my education in history centered white experiences, and to see a Chinese-American author like Lee highlighting our place in US history, telling it through a Chinese American lens, showed me that Asian American authors could use fiction to carve out spaces for ourselves not only in the literary canon but also in what we think of as “American history.” This novel demonstrates that we have been here a long time, and our stories are not only important, they’re also American stories. I don’t know that I would have had the courage to tackle historical fiction, much less a personal story like We Are Not Free, without the work of Stacey Lee.

Where Futures End by Parker Peevyhouse (Kathy Dawson Books, 2016)

Where Futures End is the kind of literary science fiction I absolutely adore. Not exactly a novel, not exactly an anthology, Peevyhouse’s debut is a series of five interconnected novellas, each moving forward in time—sometimes by decades—toward the end of the world. Beginning with one boy’s discovery of and return from a magical, Narnia-esque land, each novella also interrogates a different type of storytelling, from fairy tales to livestreaming to LARPing, asking big questions about meaning and purpose, society and technology. What I love about this book is its ambition: It’s genre-bending. It’s thought-provoking. It challenges conventional narrative structures. In Where Futures End, Peevyhouse dares us to reimagine what a book can be, and I think that kind of creative audacity is so invigorating—it inspires me to try new things, to take more risks, to be bold and inventive and different, because there are so many more ways to tell a story, and I am eager to discover them.

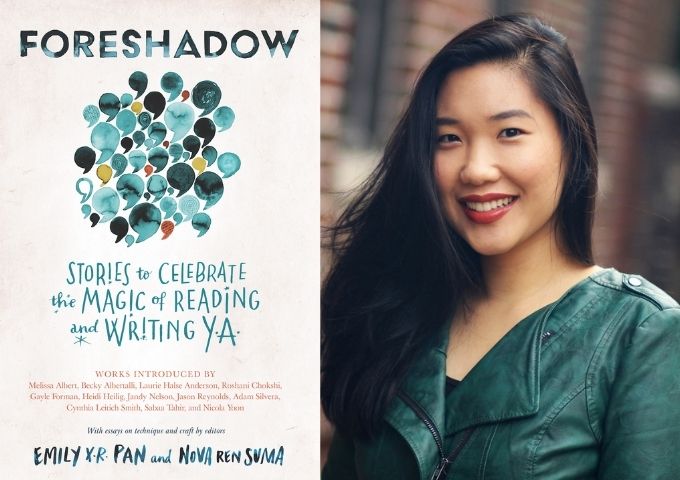

Emily X.R. Pan

A collection of 13 short stories by bold, new voices in YA fiction, ranging from contemporary romance to mind-bending fantasy, Foreshadow: Stories to Celebrate the Magic of Reading and Writing YA publishes this month from Algonquin Young Readers. Co-editors Emily X.R. Pan and Nova Ren Suma also share essays on the craft of YA fiction. Ranging from deliciously creepy to glowingly hopeful, this collection offers a master class in short stories”

(Kirkus Reviews).

How to Pronounce Knife by Souvankham Thammavongsa (Little Brown and Company, 2020)

From the title story of this collection, Souvankham Thammavongsa had my heart. As the daughter of immigrants, I saw so much of myself and my family in these razor-sharp words. There are all these complicated facets of my childhood that I only began to understand as an adult—so many memories tinged by the struggle to belong, the efforts my parents made to carve a place for me in a country where they felt so unmoored, where together our little family learned what it meant to be resilient. I caught myself holding my breath as I read these stories. There’s something about seeing those feelings and wishes drawn out so precisely and succinctly—it made me ache in an unnameable way.

Picture Us in the Light by Kelly Loy Gilbert (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, 2018)

Every book by Kelly Loy Gilbert manages to both pinch and swaddle my heart, and Picture Us in the Light is no exception. For those Asian Americans who grew up in East Asian communities with friends who shared in the experience of diaspora, this will feel like the recounting of a memory. But even for me, having grown up in majority-white communities where I was consistently the token Asian, there was something nostalgic and universal in the way this novel was told. This is a story of all the truest and most heartbreaking kinds of love, and it had me ugly crying on a plane where I was sandwiched between strangers.

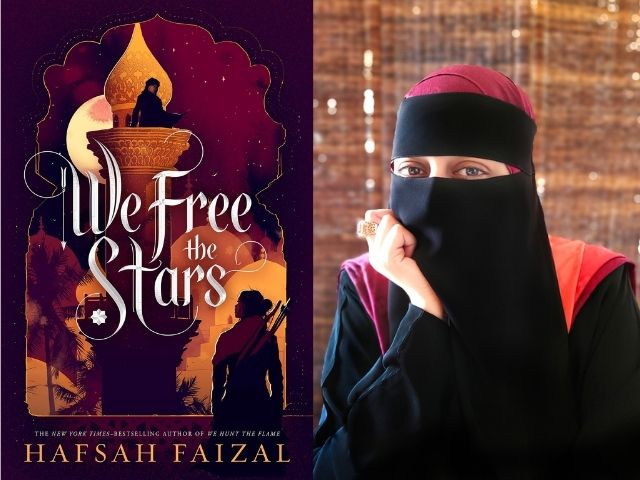

Hafsah Faizal

The fantasy sequel to the New York Times bestselling novel We Hunt the Flame, Hafsah Faizal’s We Free the Stars publishes this coming January from Farrar, Straus and Giroux’s Books for Young Readers. “Faizal bends fantasy tropes to her will to tell a fresh and gripping story about love, honor, and self-discovery that will leave readers scrambling for more” (Booklist).

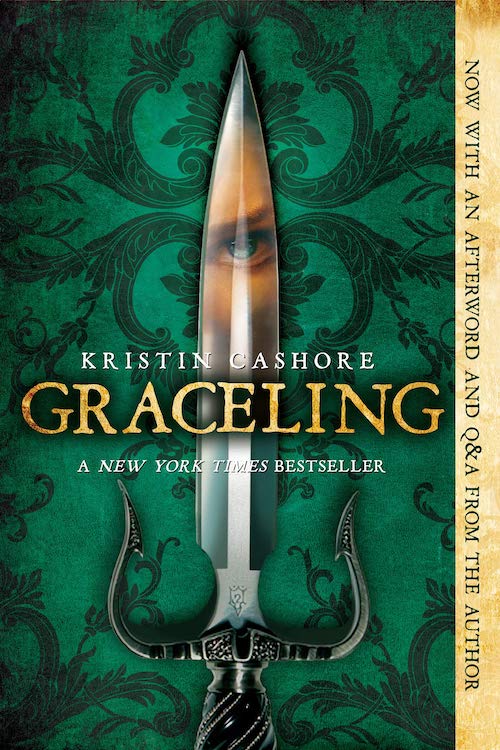

Graceling by Kristin Cashore (Houghton Mifflin, 2008)

Every author will tell you they’ve been writing since they could hold a pencil. I’m not one of those authors—when I was a child I disliked reading, so I certainly never entertained the idea of writing. That is, until my dad took me to the library when I was a teen, and I found a book called Graceling. It was the first YA book I read. It swept me away to a world where a girl like me held so much on her shoulders and had to forge her own path. Where she was misunderstood and judged and regarded differently, because she was misunderstood. Meeting Katsa in Kristin Cashore’s fantasy debut when I was seventeen was the closest I’d ever come to feeling seen and being understood. That one book opened the door to hundreds of more stories. I fell in love with reading, collecting little scraps I could relate to and holding them close. It led me to begin blogging about books, and that, in turn, led me to writing my own.

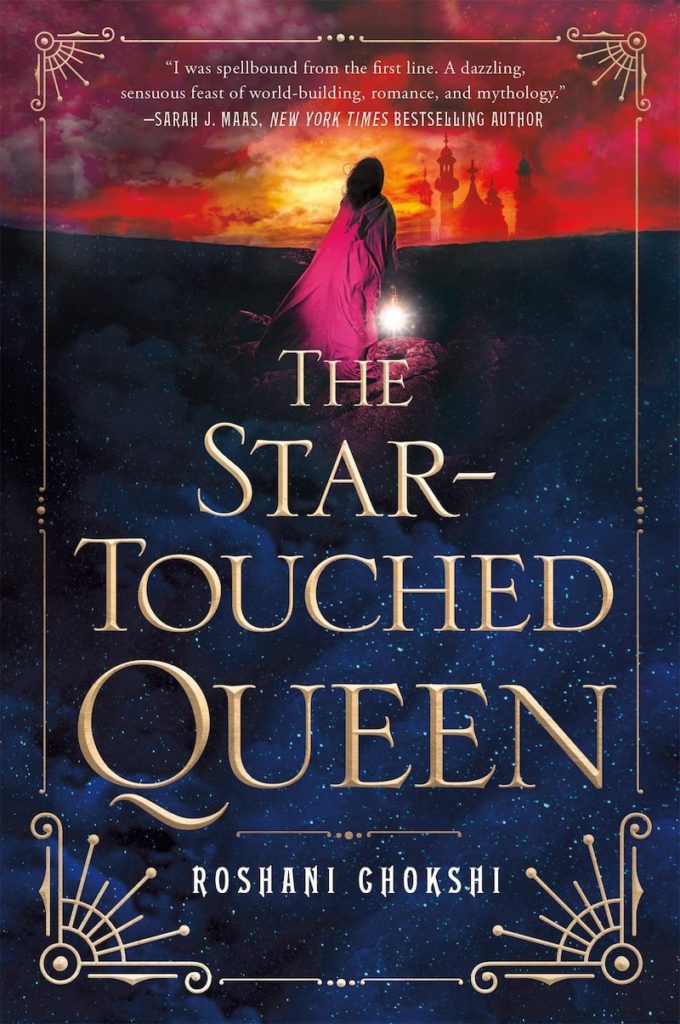

The Star-Touched Queen by Roshani Chokshi (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2017)

When I discovered Roshani Chokshi, I’d been blogging and designing in the publishing world for a few years. She had just sold her debut, The Star-Touched Queen, and though I’m sure she was also ecstatic, it felt like a victory to me. She was half-Indian, not so distant from my own ancestry in Sri Lanka—a girl with brown skin, writing a story that was fantastical and sweeping. It wasn’t about the suffering of her people, or the troubles within her culture (an inevitability in every culture). It was inherently Indian and romantic, steeped in legend and lore, where I’d only ever seen icky romanticization and exoticization before. When I was drafting We Hunt the Flame, which isn’t about suffering and oppression, but adventure and discovery, I’d been worrying that the only marginalized stories publishing wanted were those that centered on the issues we faced. The Star-Touched Queen gave me hope even before I read its celestial pages, and I’m still holding on to its enchantment years later.

Abdi Nazemian

It’s 1989, the height of the AIDS crisis in New York City, and for three teens, the world is changing. Out in paperback earlier this Spring, Abdi Nazemian’s Like a Love Story was described by fellow YA novelist Mackenzi Lee as “a love letter to queerness, self-expression, and individuality (also Madonna) that never shies away from the ever-present fear within the queer community of late ’80s New York.”

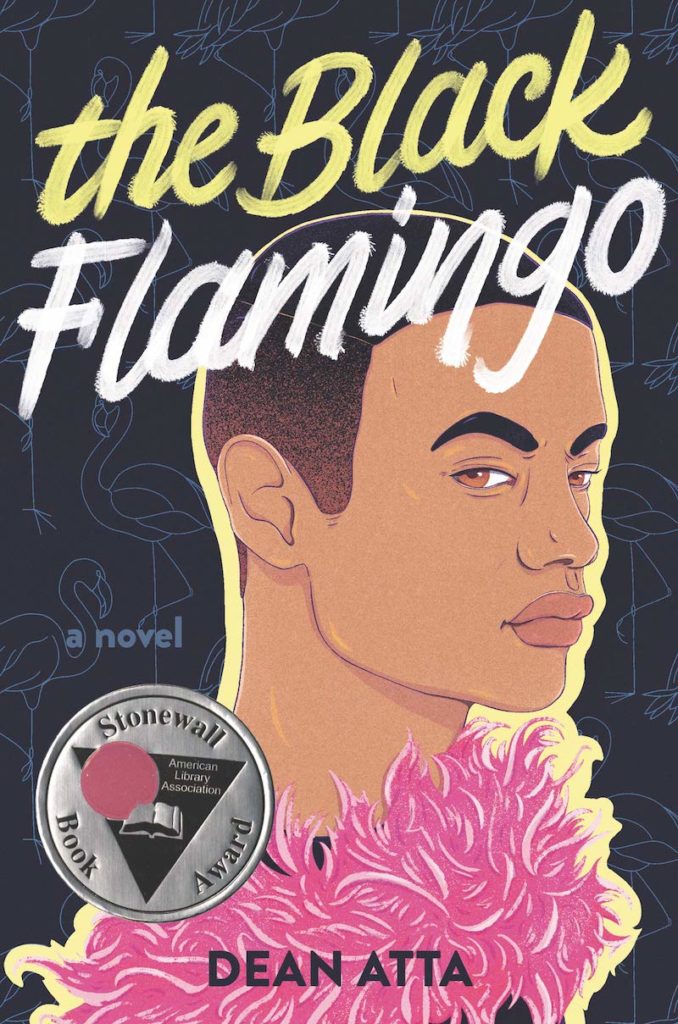

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta (Balzer & Bray/Harperteen, 2020)

Dean Atta’s novel in verse absolutely stunned me the first time I read it. It’s a work of art that is dense with specificity, humor, lyricism and truth. The book takes on a lot—race, toxic masculinity, and sexuality, for starters—but it’s always grounded in the unique experiences of its beautifully written lead character. The Black Flamingo is a story of triumph that doesn’t shy away from hard truths—it’s a book that I can’t stop recommending and that I’ll be revisiting often. It’s also one of a growing list of international young adult novels that have made its way to the United States, and I hope to see many more novels from around the world making their way here (two more that I highly recommend are Lucas Rocha’s Where We Go From Here and Vitor Martins’ Here the Whole Time).

Darius the Great Is Not Okay by Adib Khorram (Penguin Books, 2019)

As a kid, I longed for stories that would reflect my experience as an Iranian American, and more specifically as a queer Iranian American. The reason I started writing books is because I felt the need to represent my cultural experiences in hopes that no kid would feel invisible like I once did. Luckily, there are so many brilliant authors reflecting the Iranian American experience now, and I wish I could recommend them all (hi Sara Farizan, Arvin Ahmadi, Alexandra Monir, Sara Saedi, for starters). But since I only have two book choices, I’ll go with Adib Khorram’s achingly honest novel, which has an equally gorgeous sequel now. I love this novel for the loving tenderness with which it depicts life for Iranians in America and for Iranians in Iran. Khorram writes heavy subject matter with a light touch, and he brings out the humanity in a community that has so often been depicted as stereotypes.