In a new portfolio from A World Without Cages, eight incarcerated writers explore the underworld.

April 11, 2019

In the southwest corner of Utah, not far from the Virgin River and a Walmart distribution center, sits a county jail known as Purgatory Correctional Facility. Its name, enshrined in gold letters on a sign out front, is geographical—it comes from the nearby Purgatory Flats. But it also seems strangely apt. Purgatory Jail is the sort of place that Virgil would show Dante on their journey out of hell.

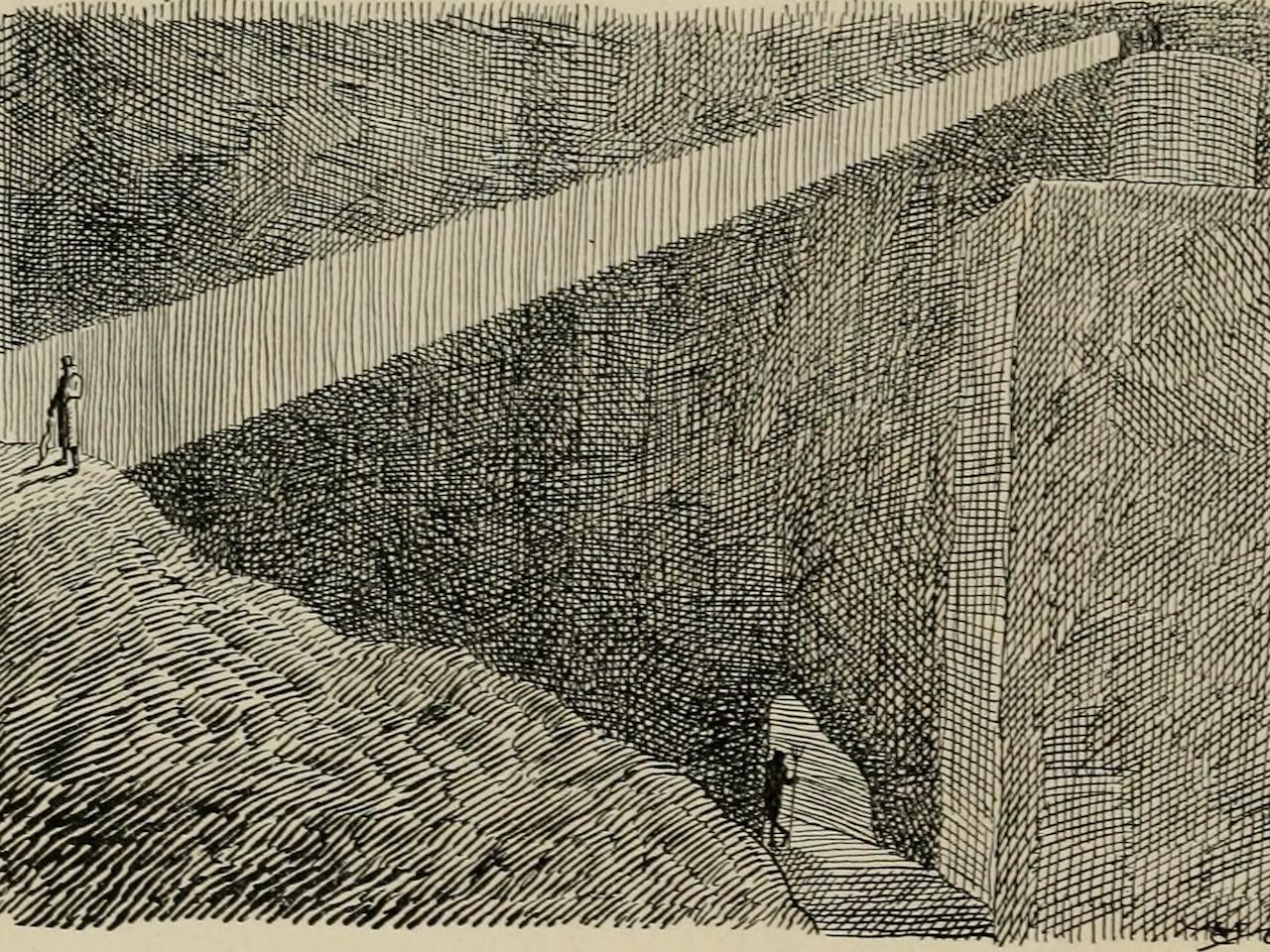

Writers in prison often make their own comparisons to purgatory, hell, and the underworld. In prison parlance, solitary confinement is “the hole,” and prison is “the belly of the beast.” In Texas, the incarcerated describe themselves as “buried.”

The newest portfolio from A World Without Cages, “Shades of Black and Gray,” traces these themes through the work of eight incarcerated writers. “I reside in purgatory awaiting judgment,” writes the poet Bartholomew Crawford in “Residence of a Sleepless Dream.” Prison, for him, is

A seven-level structure, seven stories of nothing. Where ignorance reigns like a vicious monsoon and doom is a thunderous lightning spark. But to the inhabitants here, it is no more than an amusement park….

In these poems and essays, purgatory is also a psychological condition. “Four years ago, in November, I entered my own personal purgatory,” writes Franklin Lee in “On Asian Shame.” Sitting in a six by nine foot cell, he tries to reckon with the pain he has inflicted. “I am buried by my own guilt and shame for a crime that impacted the victim, my family, and my community.”

Narratives of the underworld are as old as literature itself. According to Greek myth, the poet Orpheus followed his lover, Eurydice, across the river Styx and into Hades. His music convinced the gods to release her—but only if he could lead her to the surface without looking back. “Life Lines,” a poem by Connie Leung, seems to pick up where he left off:

so tempting

to cross

over and over againlike the river Styx

in search of lost love.if only we could learn

to stoplooking back

for each other.

Many of these writers, like Orpheus, succumb to the temptation of looking back. In “Letter to the Son I Never Met,” Dao Xiong remembers a decision that he can never reverse. In “Drop a Kite,” Fong Lee tries to send a warning to his younger self. “I am not writing you from the warmth of an office or a mansion, but the cold loneliness of a Minnesota prison cell filled with ugly secrets,” he writes. “You know now that punishments are not created by Heaven but by men.”

Yet even in the dim light of the underworld, there are glimmers of humanity. In “Buddha in the Prison Yard,” Arthur Longworth writes about an act of violence in a place of worship—and the search for compassion and enlightenment that follows. In “Chinese Laundry,” M. Monsuri writes about the afterlife of a Chinese gangster, who chooses a different path in prison.

Finally, in two poems, “Inside” and “No,” the Ojibwe poet Louise Waakaa’igan chips away at Christian idols of purity and redemption. “There are no angels on / this porcelain figurine shelf,” Waakaa’igan writes. These poems yearn for a world that is not divided into sin and salvation, darkness and light, heaven and hell. They are interested in the shades of gray, in the spaces in between.

Read our first portfolio of incarceration literature, “What No One Else Sees,” on The Margins.