The better half of her four decades of life were marked by the ebbs and flows of relapse and remission, either sick, or about to be. Remission is life with an asterisk; conditional.

July 5, 2021

Editors’ Note: The following essay by Layla Zbinden is part of the notebook I Want Sky, collecting prose, poems, and hybrid work celebrating Egyptian activist Sarah Hegazy, and the lives of all LGBTQ+ Arabs and people of the SWANA region and its diaspora. Edited by Mariam Bazeed and published as a part of a partnership with Mizna, the notebook will also be available as a print issue this summer, including pieces exclusive to that format. Continue reading work published in this series here.

“Try as we might to rid ourselves of it, in the end everything brings us back to the body. We tried to graft it onto other media, to turn it into an object body, a machine body, a digital body, an ontophanic body. It returns to us now as a horrifying, giant mandible, a vehicle for contamination, a vector for pollen, spores, and mold.”

—Achille Mbembe,

The Universal Right to Breathe, 2020

My body has taken the task of dying into its own hands.

My immune system is killing me. The irony of this statement does not escape me. My diseases are irreversible, incurable, and I am left stabbing myself biweekly with needles filled with medication that destroys the very thing supposed to protect me—my immune system. Along with that obliteration, my liver and kidneys are marked for premature failure, and I am left vulnerable to infections. I am sick. I will be sick for the rest of my life. No matter what route I take, mine is a path toward premature death, self-consumption, decay.

This decay as part of a longer lineage, a maternal inheritance, women whose names I know and many whose names I don’t, a lineage uprooted and replanted in immigrant soil seven thousand miles away; they watch [over] me from framed black and white photographs.

This decay is our shared history. It is my mother’s story. It was her mother’s before her. If I had known my grandmother—both in flesh and in language—I might have learned it was her mother’s before her. They are all women who’ve been bound to half-lives—either lives that end abruptly, or that leave them half empty, waiting—sometimes begging—for death.

I situate my own autophagy, and the chronic illness, gendered violence, and death of the women in my family, within Achille Mbembe’s conceptualization of necropolitics and death worlds, relegating us to lives of slow deaths. A “death world” is a world in which colonized subjects of sovereign powers are exposed to such harsh, life threatening conditions, that they are essentially “made to die” by the state. While some get biopolitics, and are made to live and left to die, the marginalized get necropolitics, and are left to live lives of slow death, or are made to die outright.

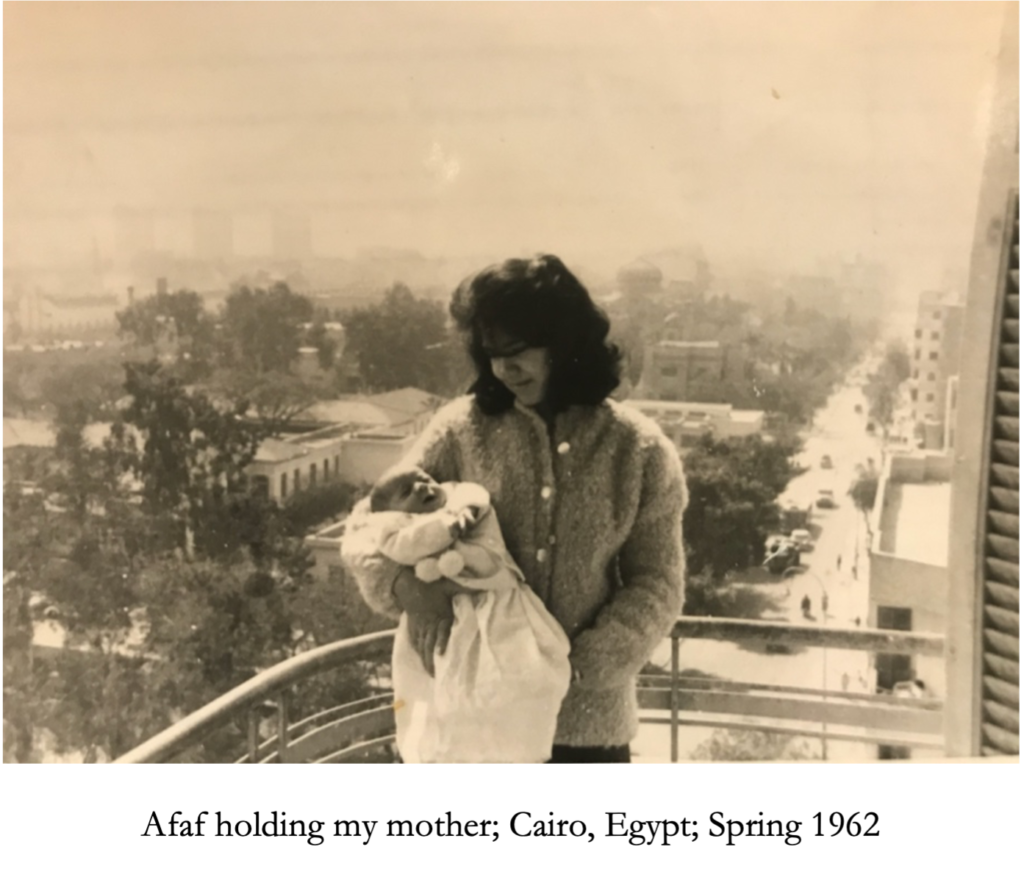

My grandmother Afaf ran outside with her favorite sister one day when she was young to play in the rain and came back with pneumonia. Chronic pneumonia—my first understanding that chronic illness runs in the family. Growing up, my mother told me that it was this chronic pneumonia that eventually killed her.

Two decades after hearing this, I underwent my own long and grueling process of diagnosis.

Joint fatigue had left me bedridden for weeks, pulsating fire radiating from my elbows and wrists and fingers, chunks of red flesh falling off my arms, hips, and hands. My fingers were so swollen that I could not grasp much at all, and when I tried, bending them ripped my skin at the seams, blood bubbling to the surface, little dots like pinpricks.

Two primary care doctors, one dermatologist, and three rheumatologists later, I finally had a diagnosis: rheumatoid psoriatic arthritis.

According to what family lore there is, as my grandmother Afaf grew older, she stayed sick, relapsing every few years as her lungs filled with fluid she could not expel. The better half of her four decades of life were marked by the ebbs and flows of relapse and remission, either sick, or about to be. Remission is life with an asterisk; conditional.

Afaf’s doctors warned her that having kids would eventually kill her.

But Egyptian women always have kids.

Afaf had three.

For the last four years, I’ve been working my way through what little there is of my family archive. When my mother immigrated to the United States she left the past behind. As she assimilated, raising her children in the liminal space of diaspora, the archive continued to shrink. One day, for example, in a fit of exasperated rage, she put a box of old photos in the alley. If I hadn’t taken them, they would have been lost forever.

On top of the scarcity of the archive itself, there exists another layer of scarcity: silence. My mother refuses to say the names of most of the people in these photos, and so they are lost to me. On the rare occasions she succumbs to nostalgia, I scramble to collect and catalogue whatever she gives me: a name, a relation, who is and isn’t alive, how they died, a memory. I am slowly and tediously forcing air into this body of photos and papers, keeping this archive alive, legible.

I sit with these photos of family and encounter them as strangers. I am deafened by the quiet. Some days it constricts my chest, forcing the air out of my lungs, laboring my breath. Other days, it surrounds me like the sea.

In her book, “Listening to Images: An Exercise in Counterintuition”, Tina M. Campt develops a strategy to approach the “quiet and quotidian” nature of state and colonial archives, by what she calls listening to images. “Listening to images is […] a practice of looking beyond what we see and attuning our senses to the other affective frequencies through which photographs register.” The archive she’s listening to are ID photos of members of the African diaspora in Europe and the Caribbean; photos she describes as being both regulated, and regulatory, as they capture state subjects in moments of silence, muteness. Rather than as markers of submission and acceptance, she reads these silences as points of rupture and refusal. For Campt, quiet is not synonymous with silence, and conflating the two is dangerous.

Through a process of relationality, Campt is able to feel what she calls “the sonic vibration” of photographs, frequencies that register in the body. How does an image move us, not only figuratively, but literally as well? How can following the detours contained in an image help us understand not only the history of that captured moment, but its future?

My mother remembers finding her mother Afaf’s body in bed on the morning of her death. In this memory, my mother is five years old.

I know this cannot be true. I know my grandmother died as my mother was graduating college because she told me. I know this memory is impossible because there is a 16-year gap between my mom and her youngest sister.

Yet the memory remains: my mother remembers that morning, she remembers entering that room. She remembers the corpse.

I look at this photo of my grandmother Afaf holding my mother bundled in her arms and listen.

While Afaf’s eyes are covered, we can see the bottom two-thirds of her face. Though we’ve never met, my grandmother’s face is familiar: my mother is the spitting image of her; I’ve been staring into Afaf’s face for years. Here she looks at my mother with a calm, affectionate gaze. Her hand looks swollen, she is probably tired. Still, she emanates warmth and kindness. Tender affection. I believe there is love in this photo.

Though the fact of her illness, and its attendant risks to her health if she ever got pregnant, were known to the family and to her husband, still Afaf had children. Though she’d been told rather specifically by doctors that having children would kill her, there was never a question in anyone’s mind that Afaf would still give birth. Afaf’s death world was as close to her, as familiar to her, as her own womb.

So she married my jiddo, had my mom, then got sick. Two years later she was pregnant again, had my aunt, and again got sick. Fourteen years later she was pregnant again, had my other aunt. Again got sick.

Four years after that she was dead.

Though my mother knows her memory of walking in, at the age of five, on her dead mother’s corpse is false, it feels real. It is real to my mom.

What truths does this memory, which is integral to my mother’s own narrative, her understanding of her own life, offer us? From it, I can fabulate that my mother grew up hungry for love, affection, doting. I can imagine her feelings of crushing despair, rage, sorrow, as my grandmother spent hours on the phone with her beloved sister, instead of playing with, even acknowledging, my mom. To a child, neglect is traumatic, the softer side of abuse.

I know this because this is another legacy I inherited. I know that parents often raise their children the way they were raised. Extrapolating from my own youth, I can guess that my mother’s formative and foundational years, were cold.

Recently, my mother succumbed to one of her infrequent sharing moods. She started talking about her childhood, Eid celebrations in her grandmother’s house, the special treatment she got from her grandfather because she looked like his favorite daughter, dead at nineteen. My mother also shared that her mom died of rheumatic fever.

“No, that’s not what you told me. You always said she died of chronic pneumonia.”

“No, Layla, I never said that. It was rheumatic fever.”

Radiating. When I have a flare up of rheumatoid arthritis the pain radiates through my joints. It is a slow, steady, pulsating pain, resonating deep in my extremities. I can feel the blood pumping, every pulse pressing on what feels like bruised tenons. My immune system sends antibodies to the joint, mistaking the swelling for infection. My tissues swell even more, and as a result of this inflammation, my joints begin to calcify: little rocks forming that deform my fingers and wrists. This calcification triggers a further immune response. My body tries to fight turning to rock, which only makes everything worse. I am caught in a feedback loop.

It is understood that autoimmune diseases are caused by genetic, as well as environmental factors. It is known that two thirds of all autoimmune diagnoses belong to women. It is also known that traumatic events can trigger the genes responsible for this autophagy.

What I can guess is that Afaf’s childhood pneumonia triggered a lifetime of rheumatic fever—inflammation of the heart valves. How painful each beat must have been. As her heart contracted and expanded it must have radiated throughout her chest, the increased blood flow ripping her heart open from within.

Psoriasis blossoms across my body, I spend my days picking at the silvery scales. If I bend my fingers my skin bursts, the sting of new flesh makes even the most mundane tasks impossible. Small pustules bubble to the surface, the clear liquid inside them breaking through and spreading across my skin.

Google tells me these are my white blood cells, dead now after decimating perfectly healthy skin.

I lie awake every morning stiff, unable to move for an hour from my body being inflamed. I lie there and cannot think of much beyond the pain. My nephew runs around the house screaming; I’ll be able to play with him by early afternoon, after the swelling subsides. I lie there and wonder how anyone could have children, be present for children, engage meaningfully with children, while being in this much pain?

No wonder Afaf had been so absent. I lie there and wonder if she is my destiny.

Knowing all this, I look again at the photo of Afaf on the balcony holding my mother lovingly, and listen again.

Somewhere between this photo and my mother’s false memory of walking in on her mother’s corpse, the tender affection captured here grew quiet.

To contextualize the space around the photo even more, I will share that while my mother was starved for affection and attention, my grandmother was on the phone with her sister, Nahed, all day, every day.

Nahed was in a marriage she was unable to leave. Her husband would not grant her a divorce, and the necropolitic of Egyptian family law at the time regulating marriage, meant she had no recourse to leave it. It is no stretch to imagine Nahed was depressed. Miserable. Isolated from her family, from Afaf, her sister, her best friend. The two women, each dwelling in her separate death world, spent every spare moment clinging to the phone, and to each other.

Sometime in the early 70’s, Nahed died. Of no particular cause, the story goes. She just didn’t wake up.

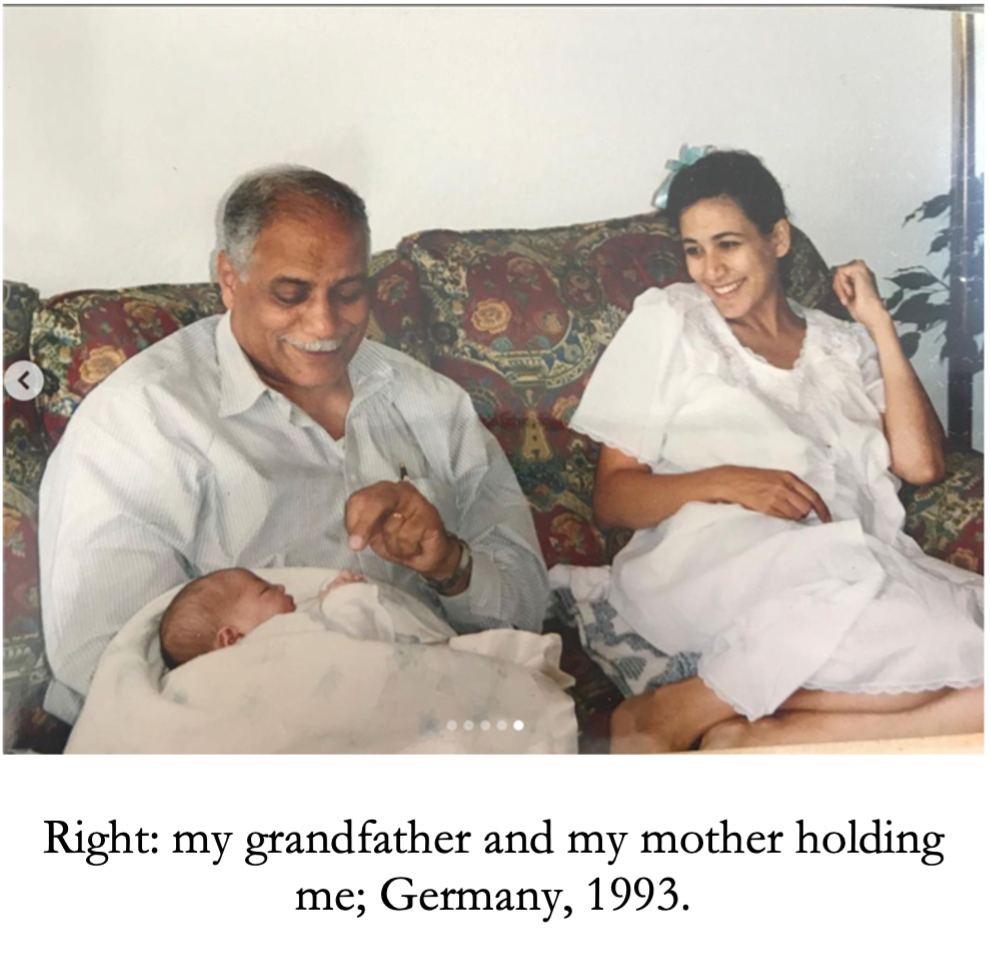

In this photo, my eyes go directly to my grandfather. I remember his visits to us spanning months. I remember him sitting in our reclining red chair watching CNN for hours, that he ate half a lime for breakfast every day, took daily walks. I remember watching him from the couch as a child, studying him, this strange and quiet man who helped me with my math homework while I struggled to understand him through the accent.

My grandfather looks proud, softer with me in his arms. My mother is beaming with joy. I do not recognize her here. I have never seen her as happy as she is in this photo. Like her own memories of hers, my memories of my mother are not warm. While my mom suffered neglect, I suffered the rage that neglect begat.

I listen to this photo, the past behind it and the future ahead. My body bears witness to these affective generational ripples of abuse. I stand caught between empathizing with my mothers pain, and reeling from the pain I hold. It is an exhausting nuance to carry.

I consider my maternal line: the suffocation of Nahed in a marriage that trapped her; the privileging of progeny over Afaf’s continued breath; my mother’s neglect and loneliness that wills her to stop breathing; the labored breath of my every morning… all coalesce into a point of shared dying under a life oppressed.

For years I have sat with this tiny archive, these silent photos, unsure of where to go, how to move through them, what to do.

I am beginning to understand that maybe the silence and the pain are not barriers, but pathways. I am beginning to see that these photos, as Campt would say, are not silent, only quiet, and that it is this quiet that compels me, an archival haunting demanding tribute.

I do not have the luxury of ignoring this body. Pain is my primary affective register, a constant reminder that we, my body and I, are tethered to each other, until death. It is a vehicle for a history of struggle and intimacy. It is my tether to the generations before me. With my collection of auto-immune diseases, and the hour of autophagy upon me, I bear witness through prognoses to these past lives. The physical pain of my decay, the pain of remembering the genealogy of loss that come along with it—they remind me that this body does not belong solely to me; that the responsibility of caring for others is a collective, intergenerational, and transnational necessity, that we are not only tethered to our own bodies, but to each other’s.