A love letter to the magazine that defined a generation.

June 12, 2012

AFTER 1989 is a series that reexamines the intersection of race and pop culture during the ’90s.

I hate the word “sassy.” Since before Jim Crow, Black women have been stereotyped and characterized in the media as outspoken, snarky, and loud. Before encountering you, I associated the word “sassy” with an asexual or hyper-sexualized caricatured representation of black femininity, rife with neck-rolling and finger snapping. While I refused to be associated with “sassy” mammies, Sapphires, and Blaxploitation stock figures, the fact that you, a magazine targeting mostly white teenage girls, were called Sassy—intrigued me.

When you disappeared into Teen’s slick pages in 1994, we lost one of the best magazines in history. I mourned you when you died so young and tragically, a righteous rebel with a cause. You lived for six years before you expired—almost as quickly as our teen years passed us by.

You were born in 1988 to provide an alternative to the condescending and superficial teen rags that maintained the status quo with tired narratives about dieting and lip-gloss. But you! Defining zits as our “beauty marks,” you celebrated our flaws as perfection and dared us to bask in our fully embodied selves.

When you left us, we lost the head of our tribe, the smart and angsty teen convener who gave us permission to fashion our own journeys towards self-recognition. I write you this love letter with the hope that you will rest in peace, knowing that your spirit remains in the hearts of thirtysomethings across America. I know I’m not alone in waxing nostalgic about Sassy-er years, when the hint of a cultural revolution seemed to exist in plain view on newsstands from Boston to Boise.

Just like Electric Youth, the pungent perfume that singer Debbie Gibson designed the year you emerged, you were a commoditized representation of a cultural shift in energy and purpose. You were a sign of a time wherein baby boomers’ children sought to leave their leftist imprint. You built the bridge between third-wave feminism and the mainstream.

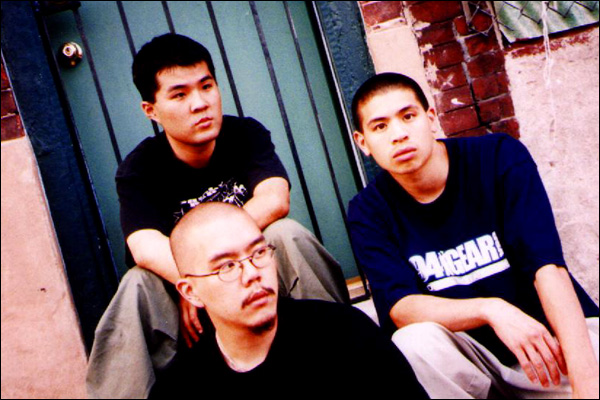

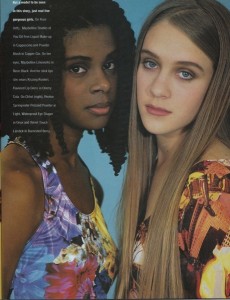

magazine’s July 1992 issue. The caption

reads, “In this story, just real live

gorgeous girls.”

It was the Hypercolored multicultural nineties and you did everything you could to cash in on cool, while also pushing the envelope. You finessed this ever so magnificently by engaging in tough conversations about race, sex, violence, street harassment, and drugs.

Even though you were determined to define yourself as anti-racist, you were the textual incarnation of affected, young, mostly white feminist angst and desire. Your investment in whiteness prevailed as you sometimes reappropriated elements of your style from communities of color.

In spite of this, by featuring your own writers as subjects, you personified the feminist concept that “the personal is political.” While your writing team was never as diverse as it could have been, your brand of participatory journalism was an early precursor to social media and blog culture, setting the tone for call-out culture on blogs, open commentary, and honest dialogues where readers and even other writers could speak their minds.

This is only one reason why I still adore you and respect the transformative potential of your legacy. When I read Sassy, the fantasy of a prevailing vibrant, anti-racist, feminist community gave me hope that the world created within Sassy’s pages might actually be mirrored someday in real life.

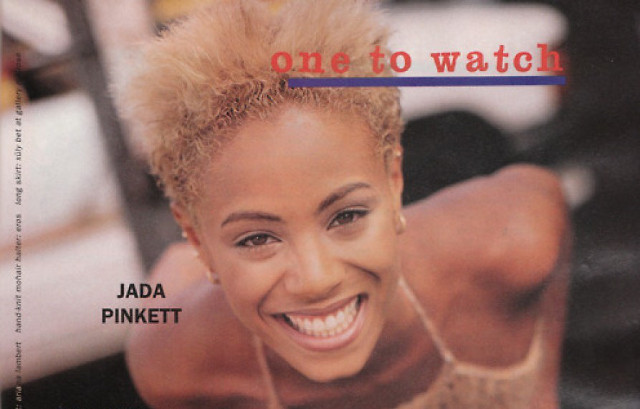

You expanded my community and my dreams of its possibilities by introducing us to Spike Jonze, Evan Dando, Jada Pinkett, and your intern Chloe Sëvigny. Unlike Seventeen, you rejected cute and focused on cool, filling your pages and covers with quirky white girls (with freckles, curls, and braces), brown girls, Asian girls, and Kurt and Courtney. In those faces—of real people with stories, problems, and triumphs—I could see myself.

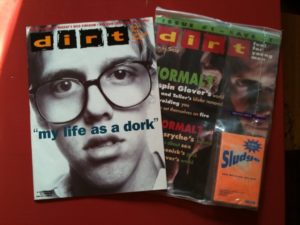

Another reason you were awesome is that the boys didn’t just want to date you—they wanted to be you. You had an in-house band named Chia Pet, featuring all of your writers and some of the hipster men who loved you. You also believed in your own hype as much as the rest of us did, spinning off Dirt Magazine for all of Sassy’s male enthusiasts.

And when you weren’t rocking out with your band or inspiring your boyfriends to start their own magazine, you were tempting me to rebel against sexism, conformity, and bullying, with real talk within the safety of your glossy pages. You altered my perceptions of media and their possibilities, while shifting my consciousness to let me know that I was not alone.

While you encouraged us to be ourselves, you also stood for community. We were turned on by your brilliance and your self-deprecating accessibility. You trusted our intelligence and could always be counted on as that non-judgmental, witty, and predictably quirky friend. You gave me and so many others hope that somewhere out there somebody understood the value of being uniquely and unapologetically who I am.

The Sassy code was powerful—if you were another teen reading Sassy, you were identified as a cultural and political kindred spirit. Headlines like “One Girl Against The Patriarchy,” on the cover of your November ’94 issue, and features like “I Am Woman, Hear Me Roar,” about fighting street harassment and sexual violence, ignited a spark that drove me to take my angst, organize, and put it into action by campaigning in the streets.

You, Sassy, were my emblem of honor and a symbol of my dissent against a mainstream teen culture that I knew I wasn’t ever intended to survive. The invisibility of girls like me and other women of color in Seventeen, YM, and Mademoiselle’s pages drove me to seek you out, a cool girls’ club in magazine form that provided me with the possibility and fantasy of teen revolution.

Thank you, Sassy, for helping me redefine your name.

Jamia