A group of artists, writers, and musicians led by Kelly Tsai is teaming up to put on a multi-media performance based on the work of Ai Weiwei

July 22, 2014

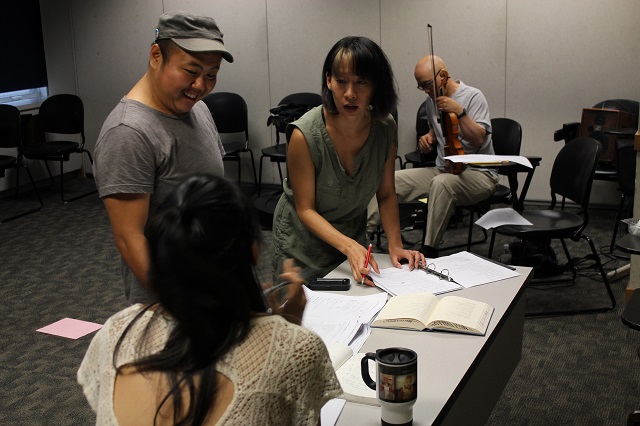

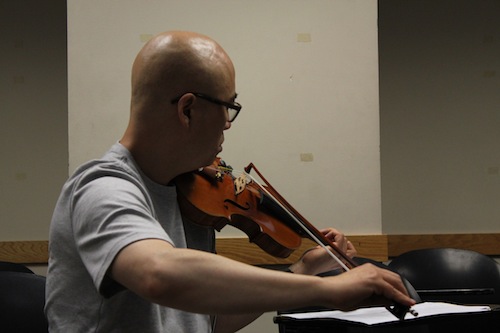

In conjunction with the exhibition Ai Weiwei: According to What, the Brooklyn Museum commissioned artist Kelly Tsai to create a one-time, multi-media performance inspired by Ai’s work. She, in turn, brought on a team of collaborators: poet Kit Yan, choreographer Jessica Chen, violinist Jason Kao Hwang, and multimedia artist Adriel Luis. Ryan Wong, Program Director at AAWW, asked Tsai and her crew about Ai Weiwei and what he means to their understandings of art, social activism, and the Asian American experience.

The program, Ai Weiwei: The Seed, takes place this Thursday, July 24. Tickets here.

What drew you to Ai Weiwei’s work? There’s a lot there: activism, social media, sculptural work, performance.

Kelly: What draws me to Ai’s work is that it cannot be categorized. He follows his impulses, and knows that art and creativity are just as much found in activist investigations as in sculpture or painting or photography. I was actually an urban planning major in college, so the nexus between creative expression, physical space, and human rights is of interest to me.

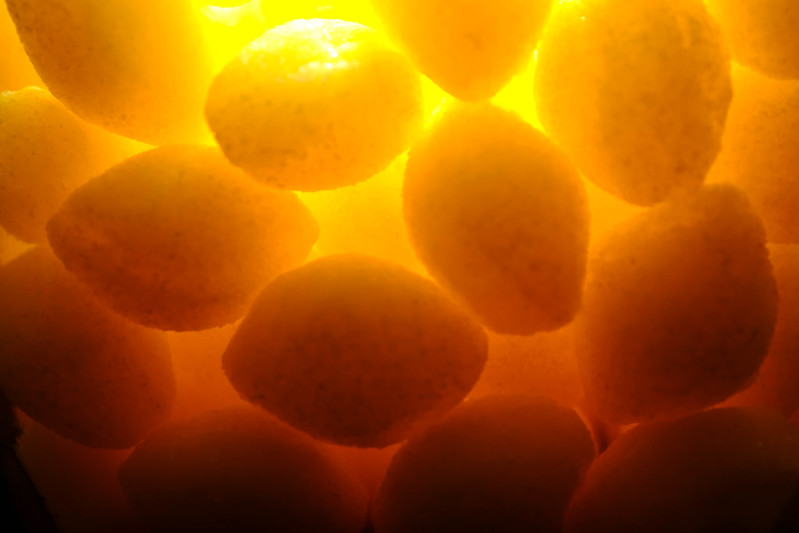

Jason: Ai Weiwei confronts outrageous government abuses with art that fuses visceral documentary evidence with a deep poetic vision: his seed of revolution grows from the individual into society.

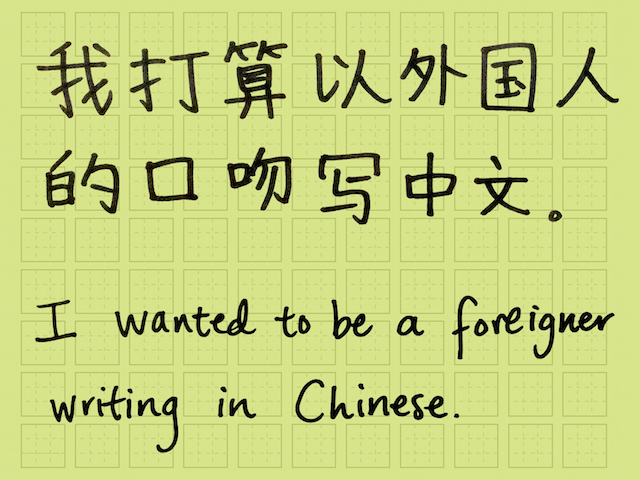

Adriel: Ai is intriguing to me because his work magnifies the stark difference between cultural expression in the U.S. and China. While his work is subtle and largely symbolic in a Western lens, it’s quite brash compared to a lot of work in China. The fact that his work has earned him such notoriety in China demonstrates a how creative one has to be in response to censorship in China.

Kit: At first, I was drawn to Ai’s work because he is Chinese. I connected with the ideas and themes in the material and understood many of the underlying feelings. After spending time with his work and story, I also feel connected with his thought process as an artist: his desire to archive, draw from text, and incorporate the people.

Describe some of the challenges in mining Ai’s biography and blog posts for performance. He’s a lively presence, to be sure, but how do you translate that to the stage, to music, to spoken word?

Adriel: Ai’s work often remixes traditional and existing concepts—a show based on that work feels like a double-remix. At the same time, much of his messaging is about the art not taking itself too seriously, even if talking about serious issues.

Jason: With my violin, I searched for a sonic language that would resonate with the select quotes that Kelly, Jessica, and Kit have sequenced and re-contexualized. I am processing the violin through a variety of FX for the right timbre and imagery to match the language. Everything I play will be completely improvised. To connect with the interior content of these words, I must respond and interact spontaneously.

Kit: There is a lot of poetry in his blog posts. Kelly did an amazing job of bringing that to the script. At first I struggled with using the modern slam poem style because it didn’t feel like it should be so harsh in tone. So I modeled many of them after the poetry of Ai’s father, Ai Qing, and then it all started to come together. I used more subtle phrasing and imagery and longer form repetition, which really tied things together.

Jessica: Rather than choreograph to Ai’s words directly, I drew from his concepts and motifs. We’ve played with the idea of manipulation, constriction, release and expression. And a lot of the movement comes in the scenes inspired by our own free writes, our own experiences.

Kelly: I went through the published collection of his blog posts from 2006-2009 and a published collection of interviews between him and Hans Ulrich Obrist (roughly 350 pages) to develop 21 short ‘found’ poems about his life from his childhood in exile to the early phases of his blog, which created the backbone for this performance. As Anna Deveare Smith says, “we speak in organic poems”: this is definitely true of his writing and his life.

Ai has been written about extensively over the last few years, including in this magazine. How will this performance alter the audience’s conception of Ai and his history? What new information or concepts do you want viewers to take away?

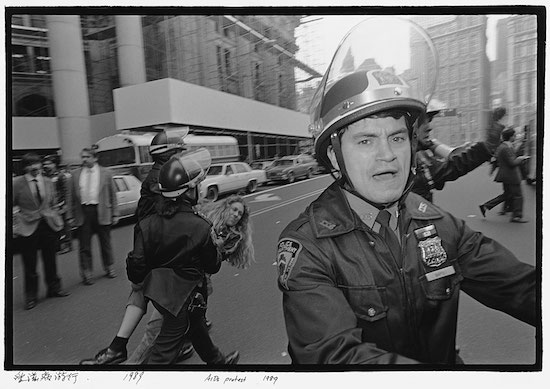

Adriel: Despite the fact that Ai has become a prominent figure in the art world, there’s a lot of effort to define him as a Chinese artist, foreign to America and its culture. But so much of his life is informed by the 12 years he spent as a New Yorker. This piece will demonstrate his impact as a Chinese American artist, as opposed to focusing on his experience with China; it will illustrate his relationship to American life.

Kelly: Sometimes it’s hard for people to identify with a person who has become an iconic activist and artist. No one springs from the womb entirely formed in their position and impact on world. I think the gift of this project has been humanizing his trajectory, especially by looking at his early years.

Jessica: In my first free write about how the Cultural Revolution impacted my family, I finish by saying that I wish Chinese families talked more. There is so much we hide from that we keep a secret. So this project is really about conversation. We want to dive into Ai’s early influences and challenges, how he got to where he is now. It’s such an important story to tell, especially given the exposure and reach he has an artist. And we encourage the audience to share their own stories.

How is Ai’s New York different from yours? I mean this both in terms of the external, of actual changes in the East Village and Lower East Side, and internal, Ai’s process of acculturating as an immigrant and expat.

Kelly: What really struck me starting on this project is that he moved here to NYC with the intention of staying. He didn’t see himself as an ex-pat. I moved to New York at around the same age that he did, but thought I might live in Taiwan. How different would my life have been? So I definitely relate to questions of home and that sense of journey.

And the folks who were active in the arts scene in the 1980’s—all the poets of the Nuyorican Poets Café and Basement Workshop—set the bloodlines that we all connect to artistically, especially in spoken word.

Jason: When Ai was here, New York City was a rapidly deteriorating, broken concrete, dysfunctional swamp. Before gentrification, the homeless were everywhere in the East Village. Abandoned buildings, drug deals on the street, prostitution and garbage: this was the environment that produced a vibrant bohemian subculture of artists and musicians.

Ai lived in New York during some of his formative years, and he’s now a global icon. Is Ai Weiwei an Asian American artist?

Adriel: Traditional understandings of Asian American contain an unspoken agreement that this identity means living in the U.S. permanently. However global communication and cultural influence are shifting this idea. Artists like Ai Weiwei and Yayoi Kusama spent substantial amounts of time in the U.S. only to move back to Asia: they are part of an story that is inescapably an element of Asian/American existence.

Kit: Whether or not Ai would consider himself an Asian American artist, I connect with his work as an Asian American. His time in NYC is pervasive throughout exhibitions of his work, reminding us that he uses the stories, techniques, and languages he learned here, itself a culture informed by colonial history and diverse immigrant narratives. Activist and writer Helen Zia tells us, “the best way to bring people together and build understanding in this global society is to openly share our stories and dreams with one another.” I believe this is what Ai is doing.

Jessica: From a logistical point of view, I don’t think he can be considered an Asian American artist because he was not born in the US and he does not live here now. He is a Chinese artist whose work is heavily influenced by his time in the US.

However, I’m not sure what the term “Asian American artist” really means. Ai creates work that connects with the Asian American experience. He also creates work that connects with the Chinese experience. And he creates work that connects with the human experience. So maybe he is a human artist?

Jason: Perhaps you could consider the work he created here Asian American, and in China, Chinese. The social issues he confronts are specifically Chinese, yet are clearly crimes against humanity that transcend nationality. The corruption he fights is Chinese, but this is also the corruption within us all. The Detroit activist Grace Lee Boggs often says that the revolution is within the individual human spirit, the ultimate battleground for hope, compassion and justice.

Kelly: I would consider him an Asian American artist. I just don’t think that intention or experience ever leaves you, especially when you’ve spent your early years somewhere you thought would be home forever. But identifying him as an Asian American artist doesn’t preclude identifying him as a Chinese artist as well.

A wise friend told me once that community is not just about who you claim but who claims you. So you can say this performance was created in the spirit of claiming Ai Weiwei as one of us, an Asian American and a New Yorker, in addition to all the other ways he’s already known to the world.