The questions of who can eat what, and where, and with whom, are facts of Malaysian life, negotiated daily and often subconsciously.

October 23, 2019

Among Malaysians, it’s an old joke that all discussions eventually find their way to food, wherever they begin. Governed by the same party for sixty-one years through increasingly divisive racial politics, corruption, and scandal, Malaysians are vehemently opinionated on matters of government, but even the stereotypical venue for our lively debates—the 24-hour “mamak” restaurant with its vast menu of hearty foods and sweet drinks—speaks of the centrality of food to our social and political identity. Of course, food is itself inherently political no matter where you are in the world: talk about food and you are, whether you realise it or not, talking about history, class, race, religion, gender, and more. In Malaysia, with the rise of Wahhabi Islam since the 1970s, food is a predictable battleground. The questions of who can eat what, and where, and with whom, are facts of Malaysian life, negotiated daily and often subconsciously.

Knowing this, I wondered if it would be possible to set in motion the reverse of the Malaysian debate we all joke about: to take food as a launching pad for honest conversation about national identity, race, religion, class, gender, and whatever other underpinnings revealed themselves. “Food” seemed too broad a topic, but thinking about elements of our dining culture that set us apart from other places led me naturally to ta pau/bungkus, the bringing home of food prepared in a kopitiam or restaurant or cafe. Takeaway meals are common in other countries, of course, but in Malaysia (and Singapore) they are a cornerstone of our culture. In urban Malaysia, where working hours and commutes tend to be long, inexpensive ta pau meals were many families’ staple sustenance long before home delivery appeared on the scene. Unlike other nations known for their passion for food, we are also a nation that never stops eating: while the French, for example, have historically shunned snacking between meals, in Malaysia, it’s acceptable to ta pau anything at any time.

Ta pau is not a recent phenomenon in Malaysia; in fact, it predates the creation of our nation state. Wrapped in banana leaves, nasi lemak was a portable meal before synthetic packaging was invented. Every Malaysian old enough to remember the days before Tetra-Pak juice boxes has drunk soya bean or Milo ais or air bandung through a straw out of a plastic bag with tough red handles. At night markets, in parks or on beaches, bags of fruit rojak or cut fruit have always come with skewers for itinerant eating—again, unthinkable in France, where even as ancient a portable food as the sandwich remains a cultural intrusion that the French have not fully made their own. And as far back as the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, my grandfather was taking his own containers to Chinese stalls to bring noodles home for his large family.

When considering the possibilities of ta pau as a topic for our folio, I thought about this act and all its actors: the Chinese stall owners under Japanese rule; my Tamil grandfather buying this food that was slowly becoming familiar to him and his wife and that would one day be as powerful a taste of home to their descendants as the food of their ancestors; buyer and seller communicating in Malay, the only language they had in common. I thought about the transformation my family’s tastebuds have undergone—from the tongues of my great grandparents, who ate only Tamil food, to my own tongue, whose strongest yearnings when away from home are for Malaysian Chinese food—and to the place of ta pau culture in the creation of our national identity and our collective memory.

My grandparents could have taken their children out to eat at Chinese kopitiams and stalls, of course, but they rarely did so: the logistics of transporting a large family into town were one obstacle, but I also wonder if the choice to bring the Other into one’s own home was the safer choice, the smaller risk, than stepping out into what might have felt like foreign territory, particularly in those early years of sharing the land that would become Malaysia.

Race and religion are my own particular preoccupations, but they are common preoccupations among West Malaysians, because racialised political and education systems are all the peninsula has known in the lifetimes of most of its inhabitants. It was therefore no surprise to me that race and/or religion grew organically out of the conversations we started for this project; even our sole East Malaysian representative, Ann Lee, has spent enough of her life on the peninsula to have become familiar with these preoccupations. But it was in talking about race amongst ourselves that we encountered our greatest challenges. I had envisioned exchanges among Malaysians, unmediated and unexplained, so that readers in the US would have the rare opportunity to eavesdrop on conversations that did not centre them or feel the burden of their presence. A minor result of this goal is that I chose to keep the original Malaysian/British spelling in all written conversations in this project, rather than the American spelling initially suggested by my co-editor; in the context of Malaysian conversations, American spellings seemed out of place.

More complicated than spelling choices was the question of how US readers would process unmediated Malaysian conversations about race. Though I had aimed for some kinds of diversity (age, race, gender and sexual orientation, professional background), the contributors to this folio all fall on the progressive end of the political spectrum. We are all people who resist received ideas about race and believe in equality, however we might think it should be implemented or encouraged. Yet our ways of talking about race diverge, in some ways, from the language favoured by progressives in the United States. Because we did not want our readers in the United States to conclude that we do not question prevalent stereotypes, our group had to make some concessions. Between us, there was much that could have and would have been left unsaid had we not had an audience to think about. Knowing each other and where we stand on the essential questions, we would have taken for granted a shared understanding of the context. But realising that the context lay too much between the lines to be apparent to non-Malaysians, we opted in a few instances for a more shared vocabulary, rather than the vocabulary that belongs to Malaysians alone.

This process of trying to see ourselves from the outside forced us to ask some difficult questions: when does our relative lack of caution with racialised/race-specific language reveal a complacency when it comes to the power dynamics of our own society, and when does it actually do what we often claim it does, keep our relationships open and honest? Where should we draw the boundaries between racist language—words like “Chinaman,” “keling,” “thulkan”—and language that simply foregrounds race or acknowledges our history of racial divisions? What you see here is the product of considerable behind-the-scenes wrestling with these and other related questions. As the guest editor of this folio, I hope both Malaysian and non-Malaysian readers take from these conversations a sense of what is important to us in this moment, a transitional period for our country and our society. Many languages bear reminders of long-ago beliefs that our strongest instincts and passions reside in the stomach or the gut: here, in these conversations that begin with stomach and home, we’ve laid bare our sorrows, fears, and furies.

—Preeta Samarasan

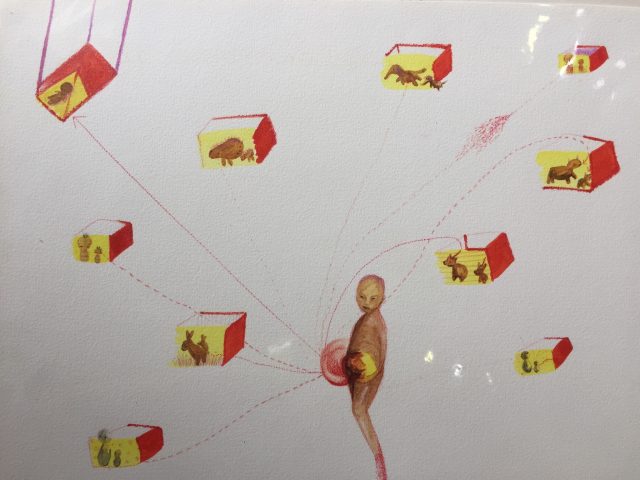

Come back over the next week to read the following pieces of Ta Pau in the Transpacific Literary Project. Artworks that accompany each conversation are by the hand of Malaysian artist and performer, Foo May Lyn.

Ta Pau: A Series of Malaysian Conversations

Food, Fingers, and What Not To Touch

a conversation with Carmen Nge, Joseph Gonzales, and Natasha Krishnan

“It often seems like all Malaysians can ever talk about is food. I think we do this because food appears neutral, seemingly benign, and unlikely to offend…” and yet. A conversation in vignettes frames how the topic of food increasingly veers from the safe into the uncertain.

The Vulnerability of Mistrust

a conversation with Ivy Josiah, Jahabar Sadiq, and Yee Heng Yeh

“When we are outside Malaysia, we are Malaysians. When we are inside, we live in fear of being overwhelmed and diluted by the other.” A video encounter gathers concerns about a country’s deterioration of trust and courage.

Codeswitching Home

a conversation with Preeta Samarasan, Marion F. D’Cruz, and Su-Feh Lee

“Eating is so intimate—you are opening your mouth and inviting something from outside of you to go inside of you.” A series of emails contemplate the nature of private/public spaces and subtle modulations of self and otherness that occur between the two.

Dialect Talks Back

a conversation with SueKi Yee, Ann Lee, and Anne Louis

“so is VERNACULAR–while charming n exotic n specific n all–necessarily exclusive and if so, not open to otherness?” A WhatsApp exchange interrogates the rules and containers for language and lives.