Grammy-nominated producer The Twilite Tone on moving to New York, working with Kanye and the South Asian namesake he shares with Chaka Khan

November 24, 2014

[Editor’s Note: This is Open City’s third installment of “Lyrics To Go,” a multimedia collaboration between Open City and Rishi Nath featuring conversations with audio and visual artists whose life and work intersects Asian-American identities and New York City neighborhoods. Check out previous installments on DJ Ushka and Mighty Crown.]

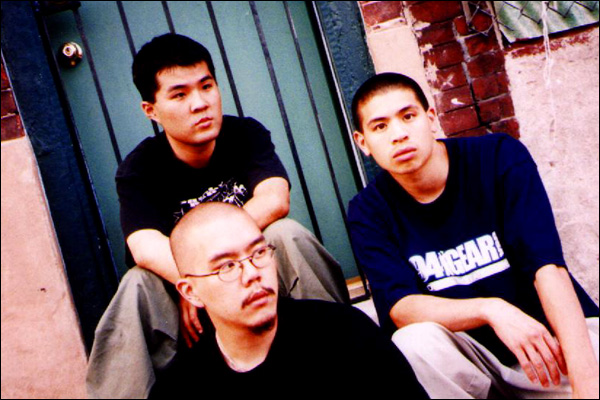

The cozy Murray Hill apartment of Anthony Khan, or The Twilite Tone, somehow manages a record library, a recording studio and living quarters.

It is here that Tone records the electronic music he has been releasing over the past several years, sometimes under aliases like Master Khan or Great Weekend. This is also where he experiments with samples and chords for his outside productions. He recently contributed to the 2012 Billboard-topping Cruel Summer, a compilation album from Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music.

The last time I crossed paths with Tone was 1999, outside The Red Dog, an edgy house music club, now defunct, in Chicago’s Wicker Park. In those days, Tone was known for his work producing, rapping, and deejaying for Common (then Common Sense), under the name Ynot. He rapped on “Can I Bust?” and appeared in the video for “Take It EZ” off Common Sense’s 1992 Can I Borrow A Dollar? LP. They drifted apart in the late 90s, and Tone began a long stretch as a club deejay.

Tone, along with graphic artist Regnoc, also founded Dem Dare, an early Chicago hip-hop party promotion crew that shook up the house music scene created by New York transplant Frankie Knuckles and by homegrown Ron Hardy. Dem Dare emphasized sophistication, lionized Ralph Lauren, and pushed for more hip-hop in clubs. Their swagger would influence a generation of young Chicagoans, including Kanye West.

While Tone’s name has become synonymous with Chicago house and with the uplift of African Americans, he has also been influenced by the cultural milieu of Louisiana and by South Asian and Native American family legacies.

I spent several hours with Tone as he unpacked from a recent trip. We discussed early Chicago house music, reuniting with Kanye West, moving to New York, and the namesake he shares with the legendary Chaka Khan.

You came up in Chicago during the birth of house music. Ron Hardy and his weekly parties at the Muzik Box were a defining moment in electronic music culture. Can you tell me something about what a Ron Hardy set at the Muzik Box was like?

People there were serious about that shit. It was like a cult that you stumbled in, and you was like – it was scary; it was something good about it, but it was scary at the same time because it was unfamiliar. And it was like, the music and the feel of it, was like – out of body, holy ghost kind of experience.

People were like, “All right Ronnie!” “Allahu Akbar!” or “Hallelujah” or “Oh Jesus!” It was like that.

And you could not even see what you were doing. It was dark, sometimes you were dancing with a girl, and, it really wasn’t about…dancing with someone you were attracted to. It was never about that. It was really about this connection you felt with the music or to him via the music.

How did you first hook up with Common?

Reg [Regnoc] and them are from a clique called the Acid Heads, which is a disco-dance crew. I’m from the South Side of Chicago, I grew up making dance music, [and] when I met Common I was singing in a dance crew. They were laughing at me! My hair was like, pshhht! – Nefertiti or some shit that got caught in some wind. I had on some [denim] jacket, with some fucked up Girbauds that I got from my friend’s obese big brother. He was a mechanic, but his jeans were fucked up and distressed and they were dope as fuck. So I’m in there singing and they come in there in their Adidas suits.

Funny! What was the track like you were singing over?

I forget, “Fragile, handle me with care,” or some shit. Me and Rasheed [Common] to this day joke about that shit. And they come in laughing. And I was like, “You guys a rap group?” And they were like “Yeeeahh.” And I was like well, “Yo I beat box, I DJ, I rhyme,” and they were like “Really?” And they scheduled an audition, and the next thing you know I was their DJ and producer.

The music and the feel of it, was like – out of body, holy ghost kind of experience.

Common was not my favorite rapper.

He wasn’t mine either. I’m glad you said that! I was my favorite rapper.

Your energy as a rapper was really interesting in that you kind of added something to his videos. Yet at some point we stopped seeing you.

There were certain things that weren’t communicated to me, that from my perception was like, “Yo, cats playing chess and I’m playing checkers,” you know what I mean. And so I started distancing myself. In hindsight I might have played myself out of position.

Then the last straw was that on the third album … I had did a record and I played it for Rasheed [Common] and he loved it. I was like, “Let’s get De La [Soul] on it.” And we’re in the studio and we’re doing a rough of a song…. When the record comes out the beat is changed, my verses are gone, and so that’s why I ultimately distanced myself. I was like “I’m done I’m done with music. I’m out.”

Had I been then who I am now, I would have addressed [the situation] as soon as I felt any business. But no, that didn’t happen that way. It was just weird shit.

Let’s talk about the legendary Dem Dare crew. Didn’t they help push Chicago, the center of house music, to hip-hop? What was their beef with house music promoter DJ Rush?

Nah. First of all let me correct you. It’s not “they,” it’s us; it’s me. I am Dem Dare – I started it, I am the leader of it; me and Reggie [Regnoc]. Two: There’s a lot of myth about the persona. We did joke and say that we were the Black Aryans. But what was interwoven into the fabric of who we were: we were trying to bring enlightenment. The problem happened because we were young guys and we come from a battle culture; we started making a competition out of our clientele.

That whole rebellion, even the first fliers saying “Rush Has Been Rushed Out,” Reggie came up with that. I actually used to give records to [DJ] Rush, to play. My cousin was a part of the Rush “clique,” and we found out they used to call us “woogies,” or what you would call “ratchet” or “ghetto.”

Not only that, we wanted to hear other tempos and other textures in the party. It was just time, like, “Yo let’s hear Soul II Soul, or A Tribe Called Quest.” Play something with some other kind of beat. And we were met with adversity.

When I moved to New York, immediately people who saw me let me know, they knew who I was and am.

How did you recently connect back with Kanye?

I reconnected with Kanye at Common’s surprise birthday party in Park City, Utah. He’s like, “Oh Shit, it’s Tone!”

I actually listened to Kanye, I engaged him in conversation. Not whatever stories that are attached to his name, none of that shit. It was like I was listening to this guy, and…he’s speaking as if he’s talking to his big brother.

Then my friend Stevie was like, “Yo you still want to go look at a movie?” ‘Cause we were going to go see a film at a theatre. I was like, yeah let’s go. Kanye was like, “Yo what do you going to see?” I was like, “I don’t know but come kick with us.” So he comes down five minutes later, and I’m gathering up records I want to edit; jazz and disco records I want to edit. And my headphones come out and the record plays out loud and he’s like, “Yo! If you’ve got any soul samples or whatever we’re working on the Cruel Summer record.” I’m like, okay, that’s cool. Somewhere in the back of my head [I’m like] “Fool, share your music with this dude!” I had a slew of music on my computer. So I just started sharing some beats with him. I was like, “Yo check this out.” The dude, for about 45 minutes, his head looked like as if it was going to come off his damn fucking body.

Then I started playing the shit I’m really into. He was like, “What the fuck is THIS?” I had been semi-retired from music up to that point. I was just doing my independent thing, that way. I wasn’t fucking with that or rap or hip-hop. So then Kanye played something to get my opinion – he played the “Mercy” beat in its embryonic state. And it was the beat with these “trap” sounds. He was like, “What do you think?” I was like I feel you on the 808s but everybody using those…why don’t we use the drums from Chaka Khan’s ‘I Feel For You?’” And that’s when the conversation on textures came up.

I got an email the next morning saying, “Yo I’ll be in New York on Monday Tuesday Thursday Friday Saturday, let’s link up!” I was like, “Okay, cool, I’ll be back on Sunday.” “Cool come to the studio.” I get to the studio, and they sat me down and it was me and his engineer Noah.

It sounds like moving to New York has been a renewal of sorts. Talk about how that move has changed your life, both in the small and in the large.

I’ve been coming to New York City from Chicago since 1989.

Now the difference for me between Chicago and New York is this. I felt like people knew who I was in Chicago but they didn’t want to let me know who I was or who I am. I felt like people weren’t giving me my just due. So for all that I brought to Chicago, bringing in all the music, bringing in the fashion, bringing this “how to be in concert with people from different neighborhoods with people from the other side of town,” all of these things weren’t happening before myself and my collective implemented those things.

When I moved to New York, immediately people who saw me immediately let me know, they knew who I was and am.

What were the specific spaces and places where you felt welcomed when you moved here?

It was really just the people subjective on the location. Case in point, I could be in Brooklyn, inside DJ Spinna’s studio. Spinna, I gotta give him much love man. He was one of the advocates for me to get out here and I still haven’t done it on a level that Spinna thought that I could and wanted me to do it on. But Spinna is one of the main advocates.

It could be in Brooklyn, it could be in Manhattan, it could be at APT, people loved me. They showed me love, gave me constructive criticism and compliments.

I like New York City, I like Manhattan, I like it because I’m constantly moving. I like that type of energy. Energy calms me. Movement calms me. Not to say that I don’t like to be still, because I meditate, I chant, I do yoga, I like that too.

I read that the root of your last name, Khan, came from Mumbai, India, and that you share that connection with Chaka Khan. What is the story?

There was a gentleman from Mumbai who came to Chicago, and I think he married who would be my great-grandmother and gave birth to my grandfather, Hasan Ali Khan, who had two children, Andrea and Hasan Khan. Andrea’s name was originally Indira but they misspelled the name in her birth certificate but they liked it. And my uncle Hasan Khan, who married Yvette Stevens, renamed Chaka and became Chaka Khan. That is my lineage to India, to Mumbai. I have some soul searching and root digging to do. I need to visit not only my family tree but the place known as India. I need to do some more excavating about that.

I came up very submerged in Louisiana culture, whether it’s the seafood or whether it’s Mardi Gras, the marching band culture, this is my culture.

And what is your connection to Louisiana?

My connection to Louisiana is very deep. My stepfather, who looks a lot like my real father, he moved me there when I was very young, about five or six, and I grew up partly there. I came up very submerged in Louisiana culture, whether it’s the seafood or whether it’s Mardi Gras, the marching band culture, this is my culture. I was blessed to be a part of a gigantic family who I claim as my family and they claim me. They don’t even think of my stepfather, Babyboy, as my stepfather, they just think of him as my father.

When they see someone who looks like them pass by on the street, they speak: hey how you doing, good evening. If you don’t speak it’s a crime. If you don’t speak up to someone from your community, it’s a crime. You are excommunicated or someone will sit and talk to you, like what’s wrong with you. That’s your people.

I learned how to fish in Louisiana. The first thing I ever caught was a baby alligator when we were fishing. I learned how to catch shrimp, crawfish, crabs; boil them, peel them, clean them, all of that in Louisiana so I have a connection. I love the language, I love the vernacular, and I love how it’s not like any other southern city or town or state in the South, it’s its own thing.

You also have a native strain in your history.

We have Native American, through marriage I have a family that is Native American. Pardon me, I need to get more clarification because it was a while ago, I tried to get to the bottom of things to get some answers and now I can’t recall the whole history. At my grandfather’s hundredth birthday some of them showed up and it was like, wow. It’s powerful, they were straight-up still holding onto the culture. They were Native Americans.

What are you really excited about now? Is it more along the lines of the electronic remixes from the Great Weekend?

No, no, I have something that I am creating and I don’t have the balls to title right now, but I can tell you that the goal is to get people to move and inspire freedom through this vehicle that I am co-creating with a collective of like-minded, spirited, talented and beautiful people.