From sufism to reggae, from construction work to driving taxis, it has been a colorful ride for one of the co-founders of a taxi drivers union in New York.

June 2, 2016

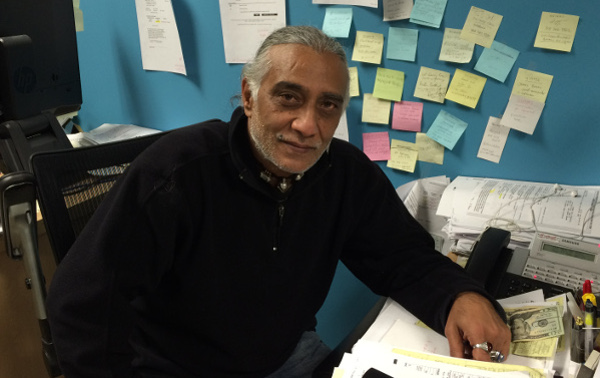

Javaid Tariq sits in the kitchen of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) office in Long Island City in Queens. With his long grey ponytail, three earrings in his left ear, and a choker necklace, he slams the table with his fist and declares in his deep, raspy voice, “Taxi drivers are the fucking pariah of New York City!”

Javaid is one of the founders of the NYTWA. He spends 14 to 16 hours a day organizing and advocating for taxi drivers in the city, about 94 percent of whom are immigrants. A former taxi driver himself, Javaid, who is from Pakistan, knew too well the problems and difficulties confronting yellow taxi drivers in New York City.

Here in the NYTWA office, he rants against two of the most pressing issues that have been chasing taxi drivers – the entry of ride-haling app Uber and the rules and regulations imposed by the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC).

“Uber is WalMart on wheels,” he says.

As for TLC: “TLC courts are basically criminal courts,” he says.

——————–

Javaid’s road to becoming a taxi driver and later an organizer did not start on a straight route. He started out as a perfume salesman in The Bronx in the 1990s, earning $27 a day.

“I didn’t have my papers or social security,” he says. “So a friend I was living with found a job for me as a salesman on Fordham Road.”

Living with nine other people in one apartment in The Bronx, Javaid found comfort and community despite the meager wage. “[The owner] had 10 of us workers. At nighttime, we’d all get together. He’d bring food and drink; we’d all sit in the park together and enjoy.”

After trying to make ends meet as a salesman for over a year, he connected with some Pakistani friends who had a construction business; they offered to pay him $40 a day. “It was kind of big raise for me, from $27 to $40,” he says. “I was a weightlifter when I was young, so construction work was a way for me to keep that going and get exercise.”

He worked 10-hour days in construction for over two years. Eventually he got promoted to “skilled worker,” and his wage got bumped up to $75 a day. He had friends who drove taxis, and eventually he thought he might be able to make more money driving—but he had other motivations as well.

“In 1994 I saw a newspaper, and they had over 50 photographs on the cover of deceased [taxi] drivers who got killed on the job,” he recalls. “Many among them there were desis — Punjabis, Pakistanis — and some Africans. I thought, these people are half a world away from home, living in America. They are working very hard, providing food back to their family. And here they got killed. Is there any security for their family, is there any pension, anything? I had no idea.”

So Javaid plunged into the taxi industry partially as a research and advocacy project, and partially to try to bring in more income. He had just taken up photography as a hobby and thought he could do some photojournalism while working as a taxi driver to shed light on the workers’ struggles and stories. “Once I became one of them,” he says, “I realized what a dangerous and difficult industry it was.”

“’The model (Uber) is bringing is the same model as Wal-Mart,’ he explains. ‘We call it ‘Wal-Mart on wheels.’ They are killing permanent jobs and just providing temporary, part-time work to people who already have other jobs. But we rely on this as our fulltime job, 12 hours a day.'”

About a year and half later, he met Bhairavi Desai and Biju Mathew who were in early discussions about organizing taxi workers. Javaid attended a meeting they had organized with 15 or 20 cab drivers and told Bhairavi and Biju, “We should do this.”

“I shared my own experience and observations as a taxi driver. They welcomed me on their team. Since that day, we keep moving on. The rest is history,” Javaid says.

Today the New York Taxi Workers Alliance has 19,500 members from over 100 different countries who drive yellow cabs, green cabs, and Uber cars. In 2011, they were chartered by the AFL-CIO to create the National Taxi Workers Alliance, the first union of non-traditional workers since the United Farm Workers (UFW) in 1962, and the first union ever of independent contractors.

——————–

With the rise of transportation app Uber’s popularity the last few years, Javaid nowadays spends much of his time fighting against what he calls “Ubernomics.”

“The model [Uber] is bringing is the same model as Wal-Mart,” he explains. “We call it ‘Wal-Mart on wheels.’ They are killing permanent jobs and just providing temporary, part-time work to people who already have other jobs. But we rely on this as our fulltime job, 12 hours a day.”

On May 10, the International Association of Machinist and Aerospace Workers reached an agreement to represent Uber drivers in New York. But Javaid and NYTWA are very critical of the deal. They argue that it does not come with the protections of collective bargaining through a union. NYTWA Executive Director Bhairavi Desai told Reuters the deal is a “historic betrayal.”

Uber has been recently valued at over $60 billion. Its co-founders, Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, are each worth about $5.3 billion.

On June 2, the NYTWA filed a federal lawsuit against Uber for “stealing wages from drivers.”

In addition to grappling with Ubernomics and the rise of the “gig economy,” Javaid raises other issues that are posing as major roadblocks that taxi drivers face as they try to make a living for themselves and their families — like TLC regulations and courts.

“TLC rules and regulations are very much unfair. TLC courts are basically criminal courts,” he says with a chuckle. “All nine millions New Yorkers can just pick up a phone, call TLC, and file a complaint [against a driver].”

“’One day I turned on the TV and there was Bob Marley’s music — that was right after he died. I was so inspired by him,’ he says with a smile. ‘Regular English songs are hard to understand, [they sing] so fast. But his songs are different, so slow. [The] rhythm was so good, and you could understand this whole poetry — revolutionary poetry.'”

He cited one case. “Passenger swipes a credit card, and it doesn’t work. They open the door and leave. You try to stop them, then they call TLC and file a complaint and claim harassment.”

As a result of what he and many drivers see as a bias against them by the TLC, and sometimes by police officers, many drivers don’t bother calling the police when a passenger doesn’t pay or even if a passenger assaults them. “If you get punched in the face, you can’t take a chance to get arrested,” explains Javaid.

“The TLC suspends your license automatically if you get arrested for any reason. So, I’m going to get my license suspended, I’m going to spend $4,000 to $5,000 in lawyers fees. It’s not worth the trouble to file a complaint or call the police,” he states. “Drivers are afraid to call for help when they’re assaulted or harassed.”

The challenges Javaid faces in his organizing and advocacy work are indeed daunting. His anger and frustration are palpable as he talks at length about the myriad ways taxi workers are exploited, taken advantage of, and disregarded by the system. Yet his spirit remains optimistic. The path forward in this fight for social and economic justice for Javaid lies in connecting the struggles of immigrant workers across industries, across ethnicities, across religions.

“Lots of organizations are standing with us and expressing their solidarity,” he says. “We are all immigrants, doesn’t matter where we’re from — South Asia, Latin America, Africa — our struggles are the same. One of us is driving taxi, one is doing construction. The female is maybe doing domestic work. The young kids are maybe being bullied in schools. Discrimination is everywhere. We all have common problems, and a lot of common enemies.”

Smiling, he says conclusively, “So with each other, with every cause, we have to stand together.”

———————-

Javaid’s tireless organizing and advocacy work has deep roots. Born in 1956 in Pakpattam, Pakistan, a small town in the country’s northeastern Punjab province, he was bothered by injustice and corruption at an early age. “I always had this [tendency to] come forward and speak out about things,” he remembers.

Javaid always had a free-spirit, rebellious side to him growing up. “My family was a very restricted, religious family,” he recounts. “I was not like that. I was more into Sufis. I was listening to qawwalis [a form of Sufi devotional music popular in South Asia].”

Pakpattam is home to a famous shrine for the 12th Century Sufi saint, Baba Farid, which draws millions of visitors every year, including Javaid when he was growing up. “In that shrine, every night from 8 p.m. to 7 a.m., the qawwalis are going on there for the last 750 years, so we used to go there and listen,” he says. “That was more freedom and spirituality there for me.”

It was only natural that Javaid got involved in student activism in college — in particular, with the People’s Student Federation (PSF), affiliated with Z.A. Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party. “He [Bhutto] was calling it Islamic socialism. He was very close to China, to Mao Zedong,” Javaid explains.

“At that time, I started reading communist literature that was coming to Pakistan. You’d get that literature in Urdu about what’s happening in China, how government is working, how public is working together in fields, factories.”

In 1977, Muhammad Zia ul-Haq staged a military coup to overthrow Bhutto, declared martial law, and officially assumed presidency of Pakistan by 1978.

“We were having so many protests, and they started arresting so many people,” Javaid recalls. “Of course, I got arrested. It was scary. People could be killed. They could be paralyzed, just for attending a protest. They started punishing some of those people in front of the public. One of my very good friends got lashes [from the police].”

In 1979, Javaid, then in his 20s, fled Pakistan out of fear for his own safety. “My father paid a lot of money to get me out, and I went to Germany,” he explains. “I was lucky to run away.”

Javaid’s time in Germany brought new perspectives to his personal and political growth. He recalls, “In Germany, I explored real Marxism and Left politics. When I was growing up in Pakpattam, there was no big library, no Internet, nothing. We had only limited information.”

However, perhaps a bigger influence than Marx in Germany was Bob Marley. “I didn’t get involved in activism in Germany, I got involved in music,” he laughs. “One day I turned on the TV and there was Bob Marley’s music — that was right after he died. I was so inspired by him,” he says with a smile. “Regular English songs are hard to understand, [they sing] so fast. But his songs are different, so slow. [The] rhythm was so good, and you could understand this whole poetry — revolutionary poetry.”

Javaid took Bob Marley’s message and spirit to heart. “I became a Rasta man,” he says. “Since that day when I saw Bob Marley [on TV], I stopped combing or cutting my hair. I grew dreadlocks. [To me, it meant] freedom, free spirit.”

“’One night my father was so angry, while I was sleeping, he cut off my dreadlocks. I was so upset. I lost my soul when he cut off my dreadlocks.'”

Never having heard reggae music before, Javaid immediately began spending lots of time in reggae clubs and attending reggae concerts. He made a lot of friends in the scene and soon became a DJ himself, spinning LPs as his dreadlocks grew longer.

“Sometimes when I’d go to a small town,” he remembers, “many times people saw for the first time people of color. Sometimes they’d ask to touch my hair to see if it’s real or not. I’d say sure, why not,” he laughs.

Javaid’s connection to long hair and dreadlocks, however, began before his introduction to reggae music. Growing up, he always tried to grow his hair long, but his father disapproved and would quickly take him to the barbershop and cut it short.

His inspiration came from the Malangs, Sufi followers who would gather near Baba Farid’s shrine in Pakpattam. “They burn the fire, they grind the bhang [preparation of marijuana leaves used in food and drink], and drink it. And they usually have dreadlocks,” Javaid says. “And there is always music, usually dhol [a barrel shaped Punjabi drum]. They are always smoking and somebody singing Sufi poetry with the music.”

The same freedom and spiritual connection he found in Sufism, he found in Bob Marley. “You could look at [Bob Marley] as a modern Sufi, modern Malang—with jeans and T-shirt. But in our country they wear long cholas, malas, and rings,” he says pointing to the several silver rings on his fingers on both hands.

Malangs were looked down upon in his family and community, however. He recalls, “In our culture, they’re like ‘no, no, no.’ Nobody would let me grow my hair or be like a Malang.”

After five and half years in Germany, Javaid went back to Pakistan—and his family was shocked by who he had become. “They sent me to Germany [one way], and I came back totally different,” he says, laughing. “I [came home] wearing my backpack with a big Bob Marley photo on it. I had my roller skates hanging off. My dreadlocks were so long. I was wearing broken [ripped] jeans. Everybody just staring at me. My father was so disappointed, he was like, ‘What the fuck? You went as a gentleman, and now what’s going on?’”

His face grows serious, and he continues, “One night my father was so angry, while I was sleeping, he cut off my dreadlocks. I was so upset. I lost my soul when he cut off my dreadlocks.”

——————–

These days, Javaid doesn’t find much time to go out and listen to reggae music, much less DJ in clubs. His hair is once again long — halfway down his back — but no longer in dreadlocks. “I used to go to SOB’s a long time ago for DJ Rekha’s [Basement Bhangra] party,” he remembers. “And in the summer, I go to Central Park Summerstage and that one in Brooklyn sometimes. I saw Third World [a reggae band] last year. I still love music, but too busy with work.”

In March, shortly after I interviewed him for this article, Javaid stood in the front row of a concert at the Bowery Ballroom in Manhattan—while I was on stage with my band Red Baraat. I was thrilled to see him finally taking a night off from his hectic work schedule to hear some music—and honored it was my music he came to hear.

Towards the end of the concert, we were playing our rendition of popular qawwali song, Dama Dam Mast Qalandar. I could see Javaid’s excitement building as he and hundreds in the crowd sang along with me. In the middle of the song, with no warning, he jumped onto the stage and, appearing to be in a trance, he swayed with us, on his knees. He swung his long grey hair around in circles with his eyes closed.

The Malang spirit was palpable. In that moment, the Bowery Ballroom felt more like a church — or more specifically a Sufi shrine — than a rock club. The lines between music, spirituality, and organizing were obliterated, and I felt lucky to experience and witness the freedom Javaid was talking about in our interview a month earlier.