Iconic New Yorkers, from 50 Cent to Rodney Dangerfield, have intersected with Richmond Hill for decades. So why does it remain absent from Queens lore?

June 28, 2012

Night was falling. It coiled underneath my hoodie, but I shook it off, walking faster. I reached the end of 130th Street and a commuter train raged above. The strip of lit panels moved quickly: men in collared whites, none looked out. Turning onto Jamaica I saw darkened storefronts—the Medisys Health Center, a Dominican Unisex Salon; farther up was the bowling alley. On the right, a pine-and-canary awning announced the El-Sam Bar. I peered through the glass door and pulled the handle. It didn’t budge. Inside, two bushy-browed men—one short, with a gold earring; the other shorter, with a gold necklace—turned from the bar.

Can we help you?

I just wanted a beer.

A very long three seconds followed. I felt my accent, clothing and beard being measured. I smiled.

The door buzzed, allowing me to enter.

It mek we proud to see a Hindustani boy like you doing good. But you must-be-careful, bai. Don’t truss everyone. The gold between Sam’s front teeth drew my attention; it made his words, the Guyanese creole, seem heavier. Three hours had passed and it was time to leave. I thanked my new friends: Suresh, Ramesh, the father Sam, even the pock-faced guy with the leather jacket. I had turned down a plate of curried pork and an offer to borrow Suresh’s second car, but I gave up at trying to pay. And I relented when Sam insisted that Ramesh—the shorter one—drive me home.

Ramesh had a silver Rav4, an unexpectedly cute car. On the short ride home, he played a Beenie Man mix and showed me where not to walk. When we reached my block, I told him to pull over. He asked me where I stayed and I motioned to the house next to mine. When we shook goodbye, I felt something knobby and glanced down to see he was missing a finger. He feigned a smile. A power saw; an accident at work. Sometimes he still felt pain. It’s stupid, he laughed. How can I feel pain when there’s nothing there?

I stood on the corner in front of my neighbor’s house, searching for my keys as he disappeared around the corner. It was my first week in Richmond Hill.

—

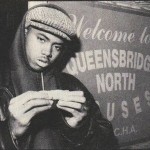

In the last thirty years, Queens—whose borders in some areas blend invisibly into suburban Long Island—has begun to be recognized as an essential part of the admixture that is New York. In the nineties, Mobb Deep and Nas rapped Queensbridge Houses into the urban cultural lexicon. Run DMC and LL Cool J did the same for Hollis a decade earlier. Howard Beach, infamous for mafioso John Gotti, continually grabs headline for its episodes of racial violence. Adventurous food junkies escaping Manhattan have recently discovered Astoria, Flushing and Jackson Heights. But Richmond Hill, the asymmetric polygon of single-family, vinyl-sided houses between the A, F, J and E trains, doesn’t have a reputation. It just isn’t part of Queens lore.

And yet, over decades, it has intersected with people central to the idea of New York City. In the 1890s, Jacob Riis, the Danish photographer-advocate, moved to 120th Street. In the 1930s, 134th Street welcomed the Marx Brothers. Yankees sportscaster Phil Rizutto (who coined the phrase “Holy Cow!”), comic Rodney Dangerfield and pop star Cyndi Lauper all attended Richmond Hill High School. In 2000, Queens rapper Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson was shot nine times and ended up at Jamaica Hospital in Richmond Hill. In a post-Tupac-and-B.I.G world, the story of his survival and recovery became a pop cultural reference, and is—in part—what propelled him to superstardom. More tragically, in 2006, when 26-year-old Sean Bell was killed by undercover police, just a few hours before his wedding, he was pronounced dead at the Jamaica Hospital. The cops had fired fifty times on his unarmed party. The case became an international symbol of police excesses. His fiancée, Nicole, became an activist.

That Richmond Hill remains invisible is in part because of its current residents, who live between categories. The Guyanese are West Indian and East Indian at the same time, but are neither black nor from India; although from South America, they speak English. Sikhs, ubiquitous here, are still a people apart. They are marked by their distinctive dress, headgear, and Punjabi language; neither Muslim nor Hindu, they are mistaken for both. And the Bangladeshis, gathered on nearby Hillside, are, despite appearances, neither Indian nor Pakistani (Bangladesh split from India in 1947 and then Pakistan in 1971). Colombians, Ecuadorians, Jamaicans, South Indian Christians, Surinamese and Trinidadians add further shades of brown to the beige-to-mahogany spectrum.

Paradoxically, it is between social margins that many—like me—find space to maneuver. To accommodate so many micro-differences, Richmond Hill has become bendable; no group has say-so over another. And as some leave for more respectable neighborhoods, others arrive from far-off villages. No territory hardens: anyone who moves here has a place.

—

Sam and Suresh, my friends from El-Sam Bar, left for Orlando, Florida, around 2008. The bar was sold for a pittance. After housing an Ecuadorean restaurant and a flower shop, it’s now an annex to a Punjabi restaurant where the spices and roti flour are stored. Inside, Indian television blares, and the smell of fresh naan and chapati constantly streams from the kitchen where unsmiling Sikh men in aprons clang steel ladles against steel pots. The restaurant does well, feeding Jamaica hospital employees for lunch and cabbies heading to or coming from Manhattan at night.

I recently bumped into Ramesh at the Portuguese wine store on 101st Avenue. He looked the same—chubby, short and festive, plus a few new white flecks in his goatee. He still lives nearby, working as a machinist. At the same place he lost his finger.