ただ空気が得体の知れぬ巨大な獸の吐息のようにねっとりと重たかった。| Only the air was heavy and moist, like the breath of an enormous, mysterious beast.

March 30, 2023

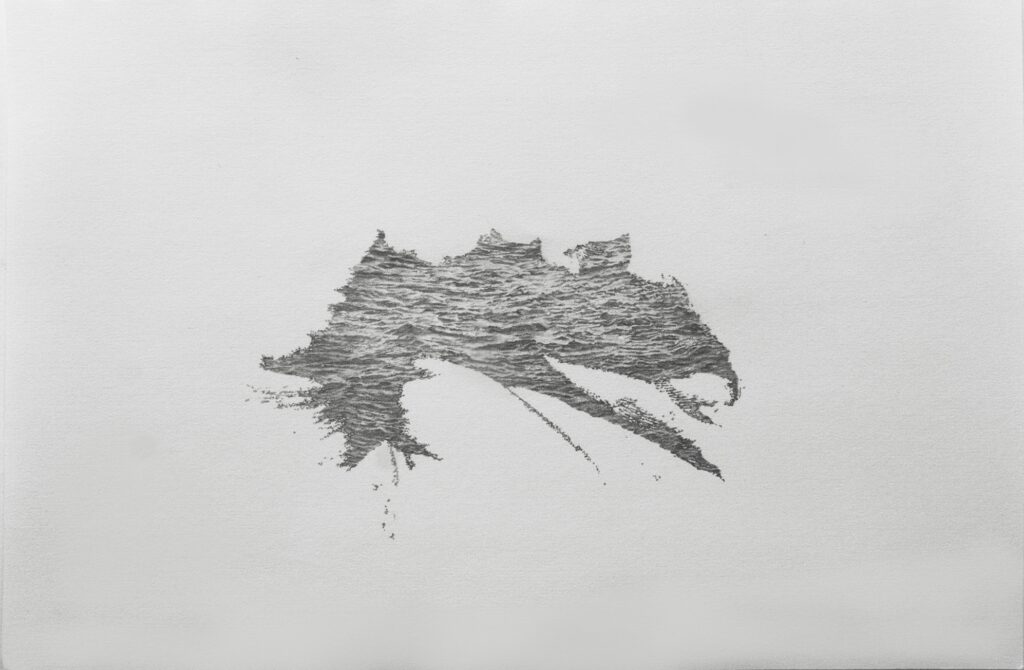

This piece is part of the Climate notebook, which features art by Katrina Bello.

子供の目には、おばあさんに見えたけれど、実際にはそれほど年は取っていなかったかのかもしれない。とはいえ、三方を山に囲まれ、小さな入江に面した小さな集落ではすでに、大人とは自分の親を除けば年寄りのことだった。その入江を埋め立てて、百メートルほどの直線道路が作られたばかりだった。道路に沿ってコンクリートブロックの堤防が設置された。それほどの高さがあったわけではなかったが、子供たちは勇気を見せつけようけとその上を歩いたり小走りしたりした。おとなしい飼い犬や飼い猫にもさわれないほど怖がりで、高いところなど論外の兄を三歳年下の私は得意げに見下ろしていたものだ。

かつてわが家の裏にはすぐに海があった。足裏に優しい砂浜ではなく、裸足で踏むと痛い形も大きさもさまざまな尖った石ころを、寄せては返す波が、小さな泡や渦巻きを描きながら洗っていた。立派な舗装道路が完成すると、次に出来たのはトンネルだった———かつては脇から張り出した木々の枝が髪や肩に触れてくる、淡い緑の光に包まれたつづら折の峠道を通って越えなければならなかった山の腹に、ずどんと直線でとなりの集落とを結ぶトンネルが貫通されることになった。山肌が削られ、ときには穴が穿たれ、海には土砂が投入されて埋め立てられ、歩行者のためにではなく自動車のために道路が整備される。そうやって集落で暮らす人たちの生活は便利になるはずだったし、実際に便利になった。けれど人々はこの地に留まることなく、まさにその道を通って、この道を辿ればいつでも戻れるからと考えたのか、次から次へともっと生活の便利な土地へ、コンビニやショッピングモールや病院や老人ホームやガソリンスタンドがそばにあって、夜空から星が消えてしまった〈町〉へ出ていったきり、戻ってこなくなるだろう。

あれは夏の日の午後だった。天気予報は台風の接近を告げていたが、低い山に縁取られた狭い空には青々と晴れ渡り、そんな気配はなかった。ただ空気が得体の知れぬ巨大な獸の吐息のようにねっとりと重たかった。昼寝から目覚めると、蟬の声がやかましかった。人の声がした。田舎の家には玄関に鍵をかける習慣はなかったので、耳には残っていなかったが、引き戸がガラガラと物音を立て眠りを妨げたにちがいない。誰かが仏様に——つまり仏壇に祀られた死者たちに——手を合わせにでも来てくれたのだろう。そういうとき、集落の年寄りたちは、かりに家の者が不在だったとしても、「こんにちは。上がるよ」と声をかけて(でも誰に? 死者たちに?)、家に勝手に入り、仏壇に手を合わせて帰っていくのが常だった。昼寝から目覚めて、仏壇から漂ってくるお線香の煙と匂いから来訪者があったことに気づくこともあった。人ばかりか、猿が訪れることもあった。こんな話を聞いたことがある。ある日、老婆が畑仕事から帰ってくると、薄暗い室内の仏壇の前で背中を丸めて頭を垂れている小柄な人の姿があったので、「ありがとう」と声をかけた。振り返ったその人の赤ら顔に照れたような笑みが浮かぶ。口の端に鋭い歯が見える———お供え物の桃を盗みに来た猿だったのだ。

しかしその日、玄関に立っていたのは猿ではなかった。おばあさんだった。背は高くも低くもなく、太っても瘦せてもいなかった。髪にパーマをあて、花と草の模様の入った薄い紫のシャツを着て、灰色のパンツを穿いていた。小さな集落なので、かりにその人の名や家の場所は知らなくとも顔を見れば誰かすぐにわかるはずだった。でも知らない人だと思った。出し抜けに、お金をくれないか、とおばあさんは言った。バス代がなくなったという。表情は穏やかだった。「今日もいい天気になったねえ」と挨拶でもするような自然さで、お金をくれないか、と言ったのだ。五百円でいいよ、と付け加えた。不思議なことに、何の疑問も抱かず、それこそ挨拶を返すように、私は五百円玉をおばあさんに渡した。ちょうど五百円玉がそばにあったのだ——たぶん仕事に出かける際に母がお小遣いとしてテーブルの上に置いていったのだ。その硬貨を握りしめたまま、おばあさんは立ち去った。

翌日の午後、台風が進路を変えて上陸した。予報では小型の台風だと言われていた。実際、風も雨も波もとりたてて激しくはなかった。そこに油断があったのかもしれない。沖に設置された生け簀の筏の様子を見るために小さな船で出かけた中年の漁師が行方不明になった。もしかして、あのおばあさんは漁師の母親だったのだろうか。いまそんなことをふと考える。しかし、もしそうだったなら、いくら何でもさすがにそのことを憶えているはずだ。漁師は生還したのだったか。そう聞いた覚えはない。死体が上がったと聞いた記憶もない。ということは、彼はいまもどこかで生きているのだろうか。母親はいまも息子の帰りを待ちづけているのだろうか。

おばあさんのことを何十年かぶりに思い出したのは、集中豪雨のせいだった。降ったことのないような雨だった、といまや七十を越える母が言った。叩きつけるような大雨が何時間も続き、集落に流れる小さな川が嘔吐でもするように濁った水を吐き出し、母の記憶では初めて氾濫した。地滑りで山の木々は根こそぎされ、山際の家々が——すでに長いあいだ空き家だった——泥土に呑み込まれた。海沿いの直線道路は地盤がゆるんだせいで陥没し、堤防のコンクリートブロックは大きく傾き、濁った海水のなかに崩れ落ちた。

わが家も水からは逃れられなかった。灰色の雲が低く迫ってくる空から落ちてくる雨がついにまばらになったあとも、いくら押さえても出血の止まらない傷さながら地面からは水がしみ出すのをやめなかった。泥水は敷居を越えて家のなかにまで侵入した。潮水だったと母は言った。でもどうして地面から海水が湧き出すのか? そのとき初めて、すぐ裏手に岩がちの海岸が迫っていた家が、百年以上前に埋め立てられてできた土地の上に建っていることを知った。

この土地に長年暮らしてきた両親の記憶にない豪雨が去り、水浸しになって汚れた——冷蔵庫は壊れた——室内の片付けがようやく終わってからのことだが、あの大雨の前の日に子供が来た、と母が唐突に言った。集落の人たちの全員を知っている母の知らない顔だった。子供の数も減り、そのために小学校はずいぶん前に廃校になっていた。いまやその頑丈な三階建ての建物が使われるのは、台風や豪雨の際の避難場所としてだった。集落に暮らす数少ない子供のひとりであれば、母にわからないはずがない。あれはどこの子供じゃろうか、と母はいぶかしんだ。雨がパラパラと落ちてきたので、母は干してあった洗濯物を取り込もうと外に出た。そのとき、通りをその子が歩いてきた。にこにこ笑っていた。目が合うと、こんにちは、と軽く頭を下げたので、はい、こんにちは、と母も応じた。じゃけど、あんな子は見たことがない、と母は首を傾げた。同じ郡内の、トンネルを数本抜けた先の別の集落でのことだが、都会の学校でうまく行かず、田舎の学校でなら伸び伸びできるだろうと、祖父母の家に預けられた男の子が、やはり河川を氾濫させて甚大な水害をもたらした集中豪雨の日に忽然と姿を消して大騒ぎになるのは数年後のことだ(その子は数日後に、神木として地域の人に親しまれていた大楠の洞で裸で眠っているところを発見されたそうだ)。いまふと、母が見た男の子はその子だったのかもしれないと考える。しかしやっぱり時期が合わない。

母が見た子は誰だったのか。その後いまに至るまで、どこの子だったのか母に尋ねていない。きょとんとした顔で見返される予感があるからだろうか。おまえはいったい何の話をしているのか、と。

いずれにしても、集中豪雨の数日後、母の話を聞きながら、なぜか頭をよぎったのはあのおばあさんのことだった。

台風の前にやって来たあのおばあさんは何者だったのか。母が集中豪雨の前に見た男の子は何者だったのか。

兄なら覚えているかもしれない、と、尋ねられたら母は答えかねない。では、あのおばあさんが来たとき、兄も家にいたのだろうか。お兄ちゃん、いたっけ? どうだったけ? 尋ねるが返事はない。母とちがって私はもう兄と話ができない。兄はもうこの世にはいない。兄のほうから語りかけてくれるのを私はただ待つしかない。

集落に留まり暮らし続けた兄は、建設現場の仕事がないときには、荒れ果てる一方の年寄りたちの家の庭仕事を手伝い、足の悪い彼女たちの代わりに墓地に参ってその家の墓の掃除をした。車で買い物にも連れていった。寺や神社の階段の石の隙間から伸びてくる草を抜き、道にまではみ出してくる空き地の草を刈った。兄は年寄り衆から好かれていた、と母は懐かしそうに言う。その事実とあのおばあさんのあいだに何らかの結びつきはないのだろうか。また、兄は若いころから集落の年少者たちをかわいがった。一緒に将棋やキャッチボールをして遊んだ。彼らの野球の試合を応援に行き、お菓子やジューズをふるまった。そうした子らはみな進学や就職で集落から出ていった。それでも兄の死を知り、兄に最後の別れをするために多くの者たちが戻ってきてくれた。兄は子供たちから好かれ慕われていた、と母は誇らしげに言う。その事実とあの男の子どのあいだに何らかの関係が見出せないものだろうか。

気候の変動について書こうとすると、どうしてあのおばあさんが脳裏に現われるのだろう。おばあさんについて書こうとすると、どうしてあの男の子を——実際に見たわけではなく、母の話で聞いただけなのに——思い出すのだろう。私は本当にあのおばあさんを見たのだろうか。おばあさんは台風の前に現われ、男の子は集中豪雨の前に現われた。母の記憶にないほどの激しい集中豪雨は、気候変動とは無関係ではないだろう。その後、たびたび故郷は季節外れの台風や豪雨に見舞われるようになったからだ。いや、「季節外れ」という表現はもはや適切ではない。いまや、あたかも四季という考え方そのものが、かつてとは比べものにならない頻度でやって来る台風によって時代遅れなものとしてかき消されてしまったかのようだった。春の尻と秋の頭を呑み込んで異様に肥大化した暑苦しい夏だけが、いまでは空き家だらけで年寄りと死者しかいない海辺の集落にまで台風や豪雨を招き寄せた。誰の関心を惹くこともなく、多くの者にとっては存在していないも同然のこの小さな土地のことを憶えているのは、貨物トラックを横転させ屋根を吹き飛ばす強風と、堤防を土台から崩壊させ道路を遮断する大水によって、現実的に、物理的に、この集落を地上から抹消しようとする異常な気象現象だけが、逆説的にもこの土地のことを忘れていなかった。この数年のあいだ、母は避難所で、あの廃校となった小学校で幾晩眠れぬ不安な夜を過ごすことになっただろう。その母のそばにはつねに兄がいた。見えないとしても兄はそこにいた。

いま母は海辺の土地ではなく、数年前に開通していまも伸びるのをやめない高速自動車道を使えば二時間足らずで行けるようになった県庁所在地にある老人ホームに暮らしている。母自身の決断というよりは、そうするように兄に説得されたからだと確信している。でなければ、母が兄の墓のある海辺の小さな集落から離れるはずがない。兄には集落の未来のすべてがわかっていたのだ。母が老人ホームに移った数ヶ月後に起きた〈前例のない〉——この表現が毎年のようにくり返されるようになっていた——集中豪雨で集落の墓地が水没することも含めて。そのことを同じ集落の出身でいまは市街地に暮らし市役所に勤める友人からの電話で知った。電話を切る前にすでに、めったに話しかけてくれない兄が私の前に現われて首を横に振っていた。だから母には何も言わなかった。

母がうちの子供たちのために送ってくれたお小遣い——五百円玉の入った小さな紙袋のそれぞれに、まだ震えの見られないしっかりとした筆跡で子供たちの名前と「ばあばより」の文字が記されていた——の御礼を言いがてら電話をかけた。「また、とてつもない大きな台風が来るようじゃの」と母が言った。母が黙ると、彼女の小さな部屋に響くテレビの大きな音が聞こえた。激しく降りしきる雨の音と似ていた。母はさらに続けようとしたが、私は遮った。兄はそうしろともそうするなとも言わなかったが、「大丈夫、大丈夫、墓のことなら心配いらん」と私は遮った。(了)

To my child’s eye she appeared ancient, but in fact she might not have been so very old at all. And yet, in that small village hugging a small inlet, surrounded on three sides by mountains, all the grown-ups, except my parents, were old. This was shortly after the inlet was filled in and replaced by a hundred-meter-long straight road adjacent to a seawall of concrete blocks. The seawall wasn’t very high, but we kids would show off our bravery by walking or skipping on it. I used to look down smugly on my brother, who, though three years older than me, was too timid to pet a dog or a cat, let alone climb that high.

Just out back from our house was the ocean. Its ceaseless waves didn’t lap a soft, sandy beach but foamed and swirled over pointy rocks of every shape and size that hurt our bare feet. Once the stretch of fine paved road was finished, next came the tunnel. Before, the only way across the mountain had been a winding path swathed in pale green sunlight, with jutting branches that caught against your hair and shoulders, but the tunnel connected our village straight through to the next one. The mountainside was scraped away, holes were gouged out, and the sea was filled in with earth and sand to build a road not for pedestrians but for vehicles. This was supposed to make life more convenient for the villagers, and it did. But the villagers didn’t hang around. They used that very road––figuring perhaps that it could always bring them back––to stream off to places where life was easier, to cities full of convenience stores, shopping malls, hospitals, senior living facilities, and gas stations, under skies emptied of stars. They moved away, seldom, if ever, to return.

One summer afternoon, the weather forecast predicted a typhoon, but the slice of sky over the mountain-ringed village was bright blue, giving no sign of an impending storm. Only the air was heavy and moist, like the breath of an enormous, mysterious beast. When I awoke from my nap, the chirr of cicadas was shrill. I heard a voice. Country folk don’t lock their doors, and although I couldn’t remember hearing anything, the sound of the front door clattering open must have awakened me. I figured someone had come to pay their respects to the household buddhas––that is, to the souls of the dead enshrined in our Buddhist altar. Even if no one was home, elderly folks would call out a cheerful “Hello! I’m coming in!” (Who were they talking to? The dead?), slip into the house, and kneel at the altar with palms pressed reverently together before continuing on their way. Sometimes when I would wake from my nap, fragrant incense smoke told me that there’d been a visitor. Not only human visitors came by; monkeys did, too. I once heard of an old woman who came back from working in the field to find a diminutive figure kneeling before the altar with head bowed. “Thank you,” she said, and the figure turned and looked at her, displaying a ruddy face and an embarrassed smile showing a long, sharp tooth in each corner of its mouth. It was a monkey, come to swipe a peach from the altar.

But that summer afternoon when I woke up, the visitor standing in the entrance was not a monkey but an old woman. She was neither tall nor short, fat nor thin. Her hair had a permanent wave, and she was wearing gray pants and a pale purple blouse in a design of flowers and grasses. The village was so small that even if I didn’t know someone’s name or where they lived, once I saw their face I could usually tell who it was. This old woman, however, was unfamiliar to me. Without any preamble, she asked me for money. She’d lost her bus fare, she said, her expression serene. She asked me for money as naturally as you might say, “Fine day today, isn’t it?” Five hundred yen would do, she said. Strange to say, I handed her a five-hundred-yen coin without hesitation, as smoothly as if responding to a pleasantry about the weather. The coin was right at hand; probably Mother had left it on the table for me on her way out. The old woman clutched the money tightly and went away.

The next afternoon, the typhoon changed course and made landfall. The forecast had predicted it would be small in scale and, sure enough, neither the wind, the rain, nor the storm surge was particularly violent. That may have caused some to let their guard down. A middle-aged fisherman went missing, having gone off in a small boat to check on fish tanks under a floating platform. Could the old woman have been his mother? The thought just now occurred to me. But if so, surely I’d remember. I wonder if the fisherman ever made it back. I can’t recall hearing that he did. Then again, neither do I recall ever hearing that he turned up dead. Could he be alive somewhere even now? Is his mother still waiting for her son to come home?

A torrential downpour made me remember the old woman for the first time in decades. “Never saw rain like this before,” said Mother, by then in her seventies. The hard, driving rain continued for hours, until the little river in the village disgorged muddy water as if retching and, for the first time in Mother’s memory, overflowed its banks. On and around the mountains, mudslides uprooted trees and engulfed long-vacant houses. The ground loosened, causing the straight coastal road to cave in and concrete blocks in the seawall to tilt and topple into the roiling sea.

Our house didn’t escape damage. Even after the rain from low-hanging gray clouds turned sporadic, water continued to seep from the ground, the way a wound continues bleeding no matter how much pressure is applied to it. Muddy water crossed the threshold, invaded the interior. Seawater, Mother said. But how could salt water emerge from the ground? I learned for the first time that our house, built so close to the rocky shore out back, stood on ground that had been reclaimed from the sea more than a century before.

After the departure of those rains that were unlike any my parents, longtime residents of the village, could recall, and the cleanup of our flooded, filthy rooms––the refrigerator had broken––Mother suddenly said, “The day before it rained, a boy came by.” She knew everyone in the village but hadn’t recognized him. The decrease in village children had long since caused the school to close; the sturdy three-story building was now used as a shelter during typhoons and storms. If he’d been one of the few remaining local children, she would have known. “Whose boy could it have been?” she wondered aloud. A pattering of raindrops had sent her out to bring in the laundry from the line just as the kid came along, wearing a cheerful smile. Their eyes met. He said a polite hello, so she said hello back. “But I’d never laid eyes on him before,” she said, her head tilted in puzzlement. In a village in the same county as ours, several tunnels away, there lived a boy who, after floundering at a city school, was sent to live with his grandparents in hopes that he would feel more at ease at a school in the country. On the day of another torrential downpour that made rivers overflow, wreaking havoc, he went missing and caused quite a stir (he turned up a few days later, curled up naked in the hollow of a huge camphor tree sacred to the villagers). That all happened years afterward. It occurred to me just now that that might be whom Mother saw. The timing is off, though.

What boy did Mother see? To this day, I’ve never asked her. I have a feeling she’d just give me a blank stare: “What on earth are you talking about?”

In any case, a few days after the torrential rain, for some reason the old woman came to my mind.

Who was the old woman who came before the typhoon? Who was the little boy my mother saw before the torrential rain?

“Your brother might remember,” Mother might well say, if I asked her. Had he been home then, too, when the old woman came? “Wait, was my brother there? I don’t remember,” I say, but there is no response. Unlike Mother, I can no longer talk to him. He is no longer of this world. All I can do is wait for him to talk to me.

My brother stayed on in the village. When there was no construction work to be had, he would do yard work for old women who had difficulty getting around and whose gardens were falling into disrepair. He tended their family graves. He took them grocery shopping. He pulled weeds between the stones in staircases at temples and shrines and mowed grasses encroaching on the street from empty lots. “Old people loved him,” Mother says, reminiscing. Could there be some link between that love and the coming of the old woman that day? My brother doted on village kids, too, often playing chess or catch with them. He’d root for them at baseball games, pass out sweets and cans of juice. When the time came for them to attend college or get a job, they’d leave the village, but even so, when he died lots of them returned to bid him a final farewell. “Young people loved him and looked up to him,” Mother says proudly. Could there be some connection between that love and the boy in the street?

When I set out to write about climate change, why does the old woman come to mind? When I set out to write about her, why do I recall the boy––someone whom I never actually saw but only heard about from my mother? Did I actually see the old woman? She came before the typhoon; he came before the rains. Rain that intense, beyond anything in Mother’s recollection, must have been related somehow to climate change. Indeed, subsequently the village was often visited by unseasonable typhoons and heavy rains. But no––the word unseasonable no longer applies. The very notion of four seasons has been all but wiped out, made obsolete by typhoons that now occur with incomparably greater frequency than ever before. Only the sultry summer, so bloated that it swallows up the tail of spring and the head of fall, summons typhoons and heavy rains to this seaside village full of vacant houses, a village inhabited solely by the old and the dead. This little place that no one pays any mind to, that most people don’t know exists, is remembered only by high winds that overturn cargo trucks and blow off roofs, and by floodwaters that collapse dikes from their foundations and wash out roads. Paradoxically, only abnormal weather phenomena working literally to wipe the village from the face of the earth have not forgotten it. Over the last several years, how many anxious, sleepless nights did Mother spend in the old schoolhouse-turned-shelter? All that time, my brother was at her side. Even if she couldn’t see him, he was there.

Mother now lives not in the seaside village but in a senior living facility in the prefectural capital, accessible in less than two hours by a highway that opened a few years ago and keeps on growing. She didn’t make the decision on her own, I’m sure. My brother must have talked her into it, or else she would never have left the village where he is buried. He knew what lay in store for the village, including that the cemetery would be inundated by “unprecedented” heavy rains (the same descriptor crops up every year) a few months after Mother moved away. I learned about the flooding in a phone call from an old friend who moved to the city and now works in city hall. Before I hung up, my brother, who seldom says two words to me, appeared in front of me and shook his head. For that reason, I said nothing to Mother.

To thank her for pocket money she’d sent the kids––for each one, a five-hundred-yen coin tucked in a little envelope with their name and “From Grandma” inscribed in her still-firm hand––I gave Mother a call. “Looks like another giant typhoon’s on the way,” she said. When she stopped talking, the sound of the television echoed loudly in her small room, sounding like a torrent of rain. She started to say something else, but I cut her off. My brother hadn’t told me to say so or not, but I jumped in: “It’s okay, Mom. Don’t worry. His grave will be fine.”