A young, incarcerated immigrant leads campaign to have charges against him dropped

March 17, 2022

(Part one of a two-part series)

The following story includes mention of suicidal ideation. Please read with care.

In a short Instagram film that went viral after his release from Rikers Island a year ago, Prakash Churaman looks directly at the camera, holding its gaze for just a moment, and says: “I was raised by the system, so when they told me, ‘yo pack up,’ I was like ‘what?’”

Amazed at being, for the moment, free, he shakes his head. His eyebrows jump in disbelief, and he breaks into a half-grin that vanishes almost on arrival.

Arrested at the age of fifteen, and interrogated without an attorney present, Prakash spent six years locked up, four of them while waiting to be tried. Prosecutors argued that he orchestrated a fatal attempted armed robbery at a friend’s home in Queens in 2014. A New York State appeals court overturned his conviction in June 2020, ordering a new trial, and bail was granted six months later. For the past year, he’s been on house arrest, monitored through an ankle bracelet.

Even as he prepares for his new trial, expected to take place this spring, he’s been campaigning for the charges against him to be dropped. Single-minded in his pursuit of that goal, his determination a magnet, he has attracted a diverse coalition of supporters and activists, from socialist party members to fellow Indo-Caribbean immigrants.

The system that he understands to have raised him is the American criminal justice system, one that, he says, “all leads back to slavery,” with police, the courts, and prisons the interlocking institutions “designed to snatch us off the streets.” Using the language of an activist, his vocabulary politicized in the snatching, he reflects: “Once those handcuffs are placed on you and you are Black or brown, you’re guilty until proven innocent.”

With no physical or DNA evidence linking him to the armed robbery, his conviction rested largely on a confession that he insists was coerced, using interview techniques that lead to unreliable statements, according to experts on juvenile forced confessions. At trial, prosecutors argued that inconsistencies in his statements to police were the lies of a callous young man who betrayed a family that had sheltered him. Prakash says that they were the confused thrashings of a teenager trying to supply the detectives with what they wanted to hear to protect himself from a murder charge—the last resort of a boy ensnared by forces beyond his control.

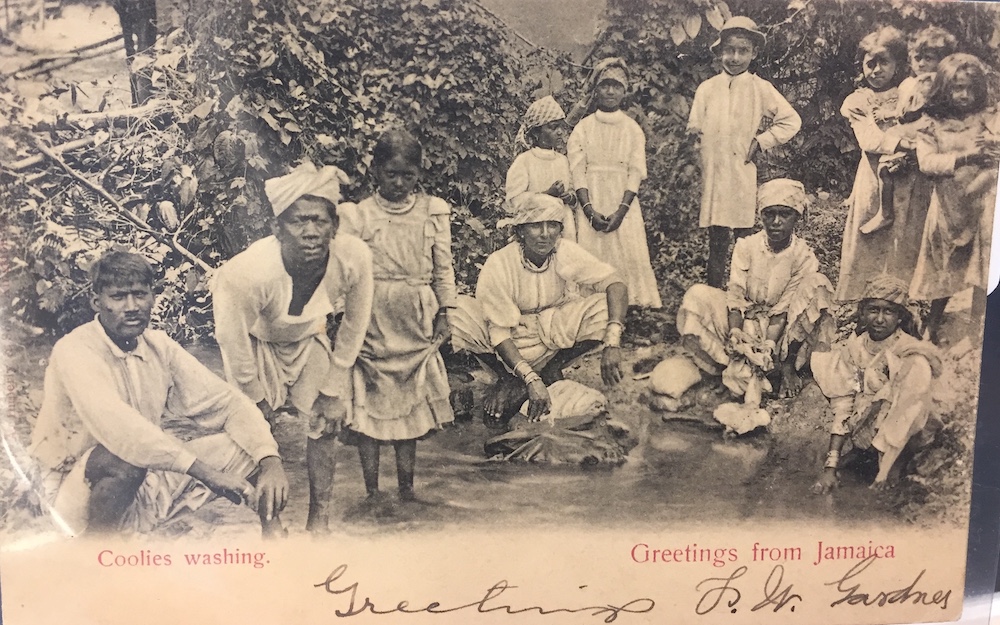

The forces that have shaped his life reach beyond the legacies of slavery in criminal justice in the United States. He was also raised by another system of unfree labor: indenture in the West Indies, which bound his ancestors, who were among more than a million Indians trafficked globally to replace emancipated Africans as plantation workers after slavery was abolished in the British empire. Indenture, like slavery, has had a long afterlife. Its traumas have persisted through the generations in the form of high rates of alcoholism among men and violence against women by their intimate partners.

Just two years before his arrest, when he was only thirteen, Prakash had acted bravely to emancipate himself from that nexus of substance and domestic abuse in his own family. In Florida, where his family had settled as immigrants, he called 911, then Child Protective Services, to report that his father, a man he describes as an alcoholic who regularly assaulted his mother, was abusing him.

“I didn’t want to be there no more,” he recalls. “I was tired of that shit.”

Rescuing himself from the primary authority figure in his life until then, Prakash showed a will to decide his own fate and to resist confining systems that would also sustain him through six years of detention, as he seesawed between despair and dogged self-advocacy. Prakash tried to kill himself more than once during those years, but he also rejected multiple plea bargains, unabashedly challenged the prosecutors and judges handling his case, steadfastly repeated his story of innocence to anyone who would listen and strategized to get that story out to a wider world. He also built relationships that were key to his survival and his speaking out.

At twenty-two, Prakash is suspended in a still unsettled struggle between his identities as fighter and victim. Tried as an adult, and given the maximum possible sentence for a juvenile, he also still wavers between manhood and boyishness, the fragile balance between savvy and naivete defining his charisma.

“I’m obsessed with him. He’s amazing,” says Rhiya Trivedi, one of his former attorneys, who helped win his appeal pro bono. Calling him “my adopted little brother who’s a shithead,” she says Prakash “exhibits a lot of maturity, presence and clear thinking, but in other senses, he’s been completely stunted by spending his childhood in prison.”

In the Instagram film made by friends, “The Prakash Churaman Story,” he projects a streetwise toughness despite an expressive baby face that betrays vulnerability through an arresting undertow of sadness in the eyes. With studs in his ears and two gold chains protruding from a gray hoodie, he bears a scar on his right cheek from a cut inflicted in prison and wears his hair close-cropped, with bangs.

It’s a wide-eyed style that the Bangladeshi American rapper Anik Khan razzed him about during an Instagram Live broadcast, as he urged his five thousand viewers to turn out to a rally for Prakash last May.

“Right now, you look like you repair BMWs and sell calling cards,” the rapper teased.

“Nah, that’s foul, bro,” Prakash shot back with a grin and the talent for making people like him and believe in him that has been instrumental to his bid to be exonerated.

He calls people “bro” often, especially the inner circle who have taken up his cause: prison abolitionists, artists whose work protests racial injustice, and advocates for working-class immigrants and the wrongfully incarcerated. The tag is a signature of his, one of the ways that he draws people close, so reflexive that he even used it several times during his interrogation by police. The reply was sharp: “Do me a favor. Don’t call me bro. Call me Detective.”

During that interrogation, as Prakash maintained his innocence, the detectives cursed at him and called him a liar. They also used two interview techniques that juvenile justice advocates nationwide have been lobbying to end, with some success this past summer in Illinois. If police mislead a juvenile suspect about the evidence they possess or the consequences of self-incrimination, the confession will now be thrown out under a new law there.

In Queens, the detectives questioning Prakash seven years ago suggested that, unless he admitted to a lesser role in the crime, he’d be charged with murder—when, in fact, admitting to any role would (and did) result in that charge. They also falsely suggested that more than one other suspect had implicated him, as the ringleader, and that he could be identified entering and leaving the crime scene on a neighbor’s surveillance video.

Four days before the interrogation, on a rainy Friday evening in early December 2014, three men wearing masks and carrying guns had forced their way into a home where Prakash, fleeing problems at his own home, had occasionally found refuge. The matriarch of that family, the dead man’s grandmother, told police later that night that she recognized the voice of the person in a mesh mask who pointed a gun at her temple. She said that, as she lay face downwards on her kitchen floor, telling him just how many grandchildren and great-grandchildren needed her alive, her captor reassured her, “Mama, me not kill you.”

The words obeyed the grammar and rhythm of the English dialects spoken in both their home countries. She’s from Jamaica, and Prakash was born in Guyana and came to the United States when he was almost six. Although she had talked with him only a few times, she swore that it was Prakash. When he was convicted in 2018, on felony murder, kidnapping, assault, and other charges, the case against him rested on the grandmother’s statement and his own.

His confession was the questionable axis on which both his conviction and its reversal turned. Noting that the evidence against Prakash wasn’t overwhelming, the appeals court ruled that the judge should have allowed the jury to hear an expert on juvenile false confessions testify. The expert had concluded in a report that Prakash may not have known or fully understood the consequences of his statements and may not have voluntarily given them.

At the start of his videotaped questioning by police, lasting two hundred minutes, the detectives read Prakash the Miranda warnings, but not the simplified juvenile version. When he waived his right to an attorney, his mother, Nandani Churaman, was with him; she has since said that she didn’t fully grasp what was unfolding. With no formal education beyond kindergarten, Nandani’s ability to read is so limited, she couldn’t meet the civics test requirement to become a U.S. citizen. One juror, convinced that the mother and son didn’t understand their rights, stood her ground against a guilty verdict for days but ultimately, after complaining to the judge that she felt bullied by other jurors, capitulated.

The lawyers who won Prakash’s appeal would later argue that his mother’s presence during the interrogation sharpened rather than alleviated the pressure that he felt. As the detectives pressed him, she matched their tone, exhorting her son to stop lying and to cooperate. Whenever they left the room, she did too, and Prakash sat alone and cried, the camera recording his breakdown.

At the time, he was exactly the age that she was when she gave birth to him.

“[It was] my first time in a room like that. I didn’t really know what to do,” she explains. “That’s why I was yelling at him to talk, like ‘If you know something, just tell them so we could go home, because I have to get to work.’”

Nandani, then thirty and a salesclerk at a discount shoe store, was struggling to raise Prakash alone. Since coming to the United States with her husband and children in 2004, she had only ever worked low-wage, precarious jobs: as a live-in nanny, a Best Western maid, a Walmart clerk.

Her marriage, arranged when she was thirteen and her husband twenty-one, had proved a prison almost from the start. In Guyana, she’d had to jump out of windows and steal into a neighbor’s backyard to escape her husband’s blows. In Florida, in two statements to police—statements she wasn’t literate enough to write in her own hand—she accused her husband of kicking her in the head and face, holding a knife to her throat, threatening to kill her, stalking her at her workplace, and forbidding her from using the telephone or leaving the house. Nandani withdrew her complaint after police charged her husband with assault, but the police reports and a protection order confirm her narrative of a history of intoxicated, violent outbursts driven by jealousy.

Soon after the attacks, she divorced him and, fearing for her life, ran as far away as she could, settling in a Guyanese American enclave in New York City, in the neck of John F. Kennedy Airport.

Left with their two children, her husband found a new scapegoat for his anger in Prakash, then eight. His younger sister remembers their father beating Prakash frequently. A photograph taken at the time shows a belt mark across his back, and Prakash reports that his father hit him on the head once with an unknown object, leaving him dazed.

About an hour after the detectives began interrogating Prakash, Nandani expressed fears about her husband’s reaction to the arrest, and the detectives leveraged that, telling Prakash: “He is going to blame her for everything. … And you put her in that situation. You put Mom in that situation.”

Suddenly bearing down, in the precinct room with Prakash, was the piled weight of his father, of the detectives, of both systems with centuries-long afterlives that have scarred him.

In slavery’s wake, indenture sowed stubborn and staggering rates of alcoholism and intimate partner violence. An acute shortage of indentured women on the plantations led to persistent and spectacular violence against them as men competed for partners, with rivals harming the women rather than each other. Meanwhile, planters used rum to quench the resistance of their workers, and their policies promoted addictions that fueled the domestic abuse for generations and still haunts Indo-Caribbean immigrant communities in New York and elsewhere. Prakash is a direct descendant of this history. His family still lives with its consequences, through the terror of his father and the wounds they have inflicted.

When the detectives brandished his father, Prakash started repeating back details that they had been giving him. He began slowly to write himself into their plot, accepting involvement in a few different, contorted, self-contradictory ways. It was a turning point in the interrogation.

For Prakash, the separation from his mother had triggered counseling from the age of eight for mental health struggles and defiance at home and school, but their reunion did not solve those problems.

The call to Child Protective Services had won him the right to live with his mother in New York City. There, he found her in another abusive relationship, with a man who once put a gun to her head and who also tried to hit Prakash.

“I just walked out,” he recalls. “I told my Moms, it’s either him or me.”

He would run and stay away all night, sometimes roaming the streets, sometimes sleeping rough in a park, sometimes sleeping on the floor at the house where the armed robbery took place, snuck in without the grandmother knowing. Prakash was friends with the shooting victim’s younger brother, and they would regularly smoke weed together at the house.

Distrustful of authority, Prakash was often in trouble. A year before the robbery, he was suspended for a few months for pushing his principal. He says that she cornered him in a hallway, accusing him of cutting class, and he was trying to get away from her. He remembers thinking: “Why are you trying to corner me? Is this jail? Why are you trying to corner me in middle school?”

School administrators advised Nandani to seek court-ordered supervision to control his behavior, advice she took, triggering events that launched him on a well-beaten pathway from school to prison. A conflict between mother and son soon after led her to summon the police, who found a switchblade in Prakash’s dresser and charged him with possession of a weapon.

At Crossroads Juvenile Detention Center in Brooklyn, where he was sent to serve a year’s sentence, he refused to eat and was put on a suicide watch. Doctors there diagnosed him with depression, signs of post-traumatic stress, and adjustment problems. They also found that he struggled with his verbal comprehension, memory, and perception. Prakash, who had a history of hyperactivity and attention deficit issues, had repeated several grades.

After a few unhappy months at the facility, he was transferred to a group home run by a social service nonprofit founded in the nineteenth century as an orphanage. Prescribed an anti-depressant, placed in special education classes, and allowed to go home every weekend, he seemed to thrive in that setting, even making the honor roll. He was promoted two grades into freshman year and released from the home months early, for good behavior.

Only two weeks later, his friend was shot and killed during the robbery gone wrong.

During his interrogation by police, Prakash gave the detectives attitude. When they pressed him about what had happened, he challenged them to tell him since, “you was there.” When told a video implicated him, he responded as an oppositional adolescent might: “I would love to see that video,” he said. Their evidence, he added, was “a lie.”

In the end, oscillating between sarcasm and crying, Prakash both accepted responsibility and abdicated it. He gave them a confession that was as much taunt as confession.

“Alright,” he said, “you all want to hear it. You can hear it. … I held Grandma at gunpoint. Yeah. Yeah. That happened. That’s what you all want to hear, so you all gonna hear it.”

At that point, three hours into the interview, one of the detectives finally explained an important nuance to Prakash’s case. Under a felony murder law banned in five states, England, and Canada but not in New York, an accomplice in a crime resulting in death can be charged with murder even if he didn’t himself kill the victim. The detective pointed at Prakash as he said the word “murder,” and his partner added that the charge would be partly “based on you not being one hundred percent with us.”

Prakash’s response was to cooperate. When they asked if he was the lookout, he shook his head, agreeing. As the detectives reassured him that they knew he didn’t mean to hurt anyone, he elaborated on a story he had offered earlier: Rival drug dealers had approached him a few days before the crime to help them get into the house, where the shooting victim’s uncle allegedly sold marijuana, and Prakash had refused. Caught there by chance when they stormed in, he told the grandmother not that he wouldn’t hurt her, but that they wouldn’t hurt her, he said.

He denied wearing a mask and continued to insist that he didn’t have a gun. A detective asked if he faked one, and apparently taking the cue, he claimed that he mimicked a gun by holding his belt. He also insisted that he didn’t know his friend’s brother was dead: “If I knew Tae had got shot, I wouldn’t have left. I would’ve killed one of those dudes,” he said, the teenage bravado giving way to tears.

At first, jail buried that bravado. Sent back to Crossroads, to await trial after pleading not guilty, Prakash was sullen and withdrawn. “He was quiet. He was to himself,” recalls Saria Ehsan, a fellow detainee who helped coax him out of that self-contained shell.

Ehsan, brought to the United States undocumented as an infant, is the son of a New York City taxi driver from Pakistan. The two teenagers, who are the same age and share roots in working-class South Asian families, struck up a friendship during their short time together at Crossroads. Their bond was the first in a network of relationships that ultimately helped propel Prakash out of prison.

“I consider him my brother,” Prakash says. “I could put my life in his hands, and I know he’d be right there.”

The pair met again in the summer of 2016, at Rikers Island, turf of the Bloods gang. Ehsan, as a member of the rival Crips, had to be feared and revered in the jail if he was to survive. Although Prakash never joined a gang, as Ehsan’s friend, he got pulled into the fray: “We had a few encounters where we had to really fight… I mean ‘fight, fight’,” Prakash recalls.

The more agonizing bout for Prakash, however, was psychological: “I guess he would battle himself,” Ehsan remembers.

On meeting Prakash again at Rikers, after a year and a half apart, Ehsan was stunned at how the infamously overcrowded, dilapidated, and dangerous jail had transformed Prakash. Cuts from self-harm tattooed his arms. He was physically unkempt, his nerves tattered. He confided in Ehsan that he felt abandoned by everyone except, perhaps, his mother. His fiercely protective son’s love for her rested, then as now, alongside his blame of her, for not protecting him from the detectives; but she was the only one to visit him at Rikers. His girl, his friends, his extended family all believed media accounts of the accusations against him. Meanwhile, the ritual of being repeatedly taken to court, held in a bullpen, but sent back to the island without appearing before a judge, seemed to take its toll.

“His ‘red zones’ were court days because he almost never saw the judge,” recalls Ehsan, who was deported to Lahore in 2020, after serving his prison sentence. “He would come back real messed up.”

Ehsan lost count of the times that Prakash tried to kill himself at Rikers. Once, he drank industrial bleach. Another time, in an open dormitory with exposed bathroom stalls, he tried to hang himself, and Ehsan, seeing this from across the room, had to wake a corrections officer, who pepper-sprayed Prakash while trying to cut him down. Ehsan and another inmate held Prakash by the legs, helped undo the improvised noose, and doused his face with milk to stop the burning from the pepper spray.

Doctors at Rikers diagnosed Prakash with cyclothymia (a disorder marked by moods that swing between mild euphoria and intense lows) and prescribed him both anti-depressant and anti-psychotic medication. Prison officials meanwhile dismissed his self-reported symptoms of paranoia and hallucination—he had heard a dead friend’s voice during solitary confinement—as a strategy to get his needs met.

In the years Ehsan spent with him, Prakash alternated between suicidal thoughts and acts and a goal-oriented, laser-like focus on his case.