On the 150th anniversary of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad, Paisley Rekdal revisits the legacy of the Chinese railroad workers who reshaped the American West.

May 13, 2019

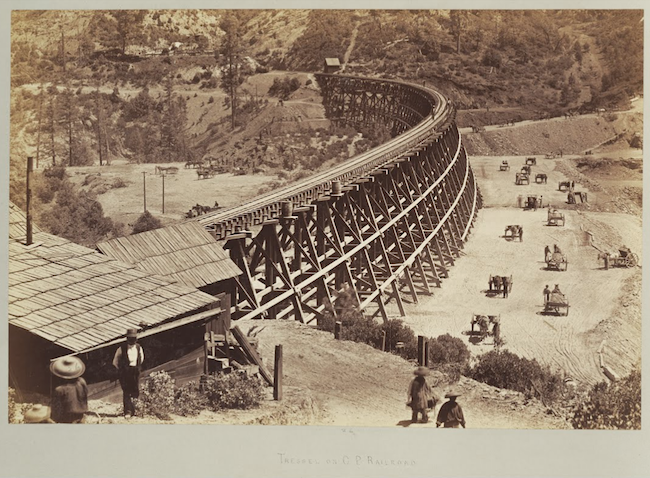

Utah Poet Laureate Paisley Rekdal has been hard at work on a book-length poem and multimedia project about the Transcontinental Railroad. Titled “West: A Translation,” the book centers the histories of Chinese workers as well as African American and Native workers who built the railroad as well as the impact of the railroad on the land and our cultural memory today. Commissioned by the Utah Arts Council and Spike 150 for the 150th anniversary of the completion of the railroad on May 10, 2019, “West: A Translation” is written as a sonnet cycle, and Rekdal has been performing it alongside audio recordings and video projections.

The more than 60-page work is expansive, broken up into sections. The titles of the poems we’ve excerpted below from the longer work come from characters in a Chinese poem written by a detainee from Angel Island elegizing the suicide of another detainee. As Rekdal shared with us:

This anonymous poem, and Angel Island’s detention of Cantonese people, was a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882, thirteen years after the Transcontinental was completed. I see these two events in history as linked, as the Chinese—once seen as a source of cheap, inhuman labor—were sought after by the Central Pacific Railroad in order to complete the Transcontinental. After the railroad was completed, however, the Chinese were seen as a threat to both white labor and ideas of white purity. My poem, “West,” translates the Angel Island poem character by character through the Chinese and other railroad workers’ stories, as well as the railroad’s cultural impact on America. Several of the poems also use found text and language culled from 19th Century journalistic and novelistic accounts of the workers and the railroad.

“[W]hat fascinates me about the Transcontinental is that as much as it unifies it also divides in as much as it offers people more and more economic opportunities that also take some of those opportunities away for other people,” Rekdal told Diane Maggipinto of Utah NPR member station KUER. “[It]’s important to see the Transcontinental in its full ambivalence ambiguous and complex glory to really get a sense of what that history means.”

The following poems are short excerpts from the much longer work, “West: A Translation.” Rekdal performed the poem at the National Postal Museum for the Smithsonian Institute on May 11 alongside Regie Cabico and Marilyn Chin, and at the Salt Lake Acting Company on May 6 and 7, before staged readings of David Henry Hwang’s “The Dance and the Railroad.”

噩 耗/Sorrowful news

sings the telegram, and Lincoln’s body slides

from DC to Springfield, his infant son, Willie, boxed

beside him. Buffalo, Cleveland, Painesville, Ashtabula.

Two coffins, 1700 miles, 14 days on 14 railroads.

One day a great line will unite us, the president

promised. Father and son displayed

capital after capital. Louisville, New Albany,

Baltimore, Chicago. The black trains beach

upon a tide of roses. Can you believe still

in the promise of this union? I saw, General Dodge

wrote, a little negro drop on his knees and offer prayers.

While above the dark news thrums on wires, gone

gone gone gone, across poles tall as the ones

from which the president ordered 38 Sioux be hung.

實可/Indeed

“The truth is, they are getting smart,” E.B. Crocker

They look down even with contempt

upon our newer, rougher civilization: they do not

identify with this country; their great care

is to be buried at home, though our demand for them

daily increases. We want 10,000

of them, we want 100,000, we want a half a million

to bring the price of labor down. There shall be

500 cubic feet of air between them, restrictions

made upon their testimony

against white men, they shall not walk

on the sidewalk or marry a native

man or woman. All this, and they will keep

the Negro steady. They are quiet, good cooks, good

at almost everything they are put at. Indeed,

the only trouble is, we cannot talk to them.

尸/Body

“Their body’s labor will override the prejudices of the soul,” Samuel Bowles

A car load passed last night, their bones

returned in barrels marked “pickles.” Thick

as bees, ants, locusts, Celestials

lay siege to Nature

in her strongest citadel. Their genius

is imitation; show them once

to do a thing, and their education

is complete. Wherever you put them,

you’ll find them good. They can withstand

freezing, hunger, thirst and heat; their simple,

narrow, but not dull minds running

in old grooves. Congealed quantities. Crystals

of social substance. Eunuchated

as boys or sodomites, they breed,

defunct, in the heat of germs. They can be shipped

to shore in great quantities. Even their clothes come,

identical, studded with rivets.

回/Return

If falling leaves return to roots, what grows

when leaves cannot be gathered?

What returns if not the body? What remains

if not the soul? Who is to say these graves

empty of their bones mean only loss, not

that these men escaped death’s hold entirely:

they are not home, but they are not here,

either, or have become so full of here

we need another word than gone. So throw

out the cormorant, its leg tied with silk ropes.

Let it drag the air for memory. Over and over,

as many times as you want. You can’t snare

what isn’t missing. This country claimed their bodies.

It never trapped their souls.

悔/Regret

from Anthony Trollope’s North America, 1862

This country reels from war. It strains

beneath the weight of an excessive patriotism

which compels the North to crush

all those who dare rebel against

the Stars and Stripes’ authority. Nothing

is more tyrannical than strong popular feeling

among a democratic people. Women, too,

a certain class, appear infected by it, who drag

their misshapen, dirty mass of battered

wireworks they call crinolines here

through the station, demanding every

strangers’ attention and protection,

while haranguing any man they suspect

of shying from the fight. The touch

of a real woman’s dress I find delicate:

but these blows from a harpy’s fins

are loathsome. She inserts herself

into the carriage, looks you square in the face,

and you rise from a deference

to your own convictions to give her

your seat, even as men–laborers many, some

infirm or aged—stand

to let her pass. Some matrons even now demand

a private carriage: to guard, they say,

their sensibilities. But I regret I’ve seen

no delicacy in them, and why should men

expose themselves to cutpurses and ruffians

if they are gentlemen? I wonder, if the train

makes some free to demand protection,

when the tasks now done by men have shifted

to the shoulders of women, will women themselves

complain? What shall they regret

when the spirit of their democracy’s reshaped

in the image of their grievance? At night,

in the train, I watch these women rock

in the oil lamps’ brassy glow, our carriage gleaming

with teakwood and soft leathers until,

for a moment, all my companions

look companionable, their faces bright, contented,

whole. The train rocks, and the lady

beside me drops her book, and when

I bend to retrieve it, she looks up,

her broad face blushing in the gloam,

for a moment, both of us transported

to some notion of our better selves. Is it sentiment

or labor that finally cements a nation,

and can strong feeling but only sow

more division when the cause for it

subsides? “Union Station,” the porter calls,

and a man limps past, his cheek

bisected with a livid scar my female

companion notes with melting sympathy

a moment, before he shrugs his traveling case

close to his side, and once more the lady

turns to face her window.

含 愁/ Hold Sorrow

Imagine a farm, a famine, your mother promised

you’ll learn tailoring. Imagine your father pocketing

$600. Now here’s the boat, its black planks wet

with fog. Here is the room holding a bed, no

mirror, your washbasin. You have one window, wired,

to face the street. He will keep his pants on,

his greasy shirt, his shoes. Imagine the quarter

pressed after into your palm. Your street

will be named for presidents you never heard of,

the city’s lights like strings of blood

in rain puddles. Imagine, if you could, you’d carve

your father’s name on a knife tip. At night,

only the train cries. Your door locks from outside.

思 鄉/ Miss Home

I pick up my life and take it

with me and I put it….

Any place…. that is not Dixie,

Langston Hughes

Ways to die: blasting accident, derailment, boiler

crack. Crushed between trains crossing

at night. Electrocution, bad food, heart attack.

You can work yourself to death, a la John,

a la Henry. Or you can stay at home, and die

anyway: fist and noose, club, gun, knife

in the back. Gossip. Sharecropping. Bottle of rum

with gas-soaked rag. What is freedom

but the power to choose

where you won’t die? What is a train

but the self once yoked to terror loosed

into a force that glides

on heat and steam? You’re so far

from Mississippi, the UP boss said

when we hit Rock Springs. Don’t you miss

your home? Miss home? I told him.

I’m hoping to miss it entirely.

來/Journey

Robert Smithson on AJ Russell’s photograph of the Transcontinental

This excessiveness of men

spilling, crowding

to mark their X of time

and money, I find

lamentable— their little moment

composed of paper

and light: alienated

spike, relic

in the hands of those willing

themselves be relics, too. Nothing

so linear as human

ego and desire, while the past

turns and returns, indifferent, spirals

like these pelicans journeying

over the red

waters of Rozel, streams

of purple; yucca rimed

with pustules of dust.

Each one lifts, rises: finds

what only some part

of its cells remembers, nests

in the wreck

of what we’ve left, this bulk

of ruined train, its wheel wells

turned the rust

of flaking blood. Of course

they trekked the human

bodies out. We care

for our own, we care

nothing for our own,

making our lives material

so as to free us better

to forget. Who remembers

the names behind those grasping

fingers in the photo? Who recalls

the dead the UP ferried

from its ancient

crash? The metals it left

not as memorial to them, but because

it cost less

to leave the evidence

than drag it all back out.