Scholar Vivek Bald chronicles an early lost history of a time of Black-Bengali racial solidarity

February 20, 2013

I have recently been thinking about the blurred race politics of early Twentieth Century activist Taraknath Das. Das was an anti-colonial Bengali organizer in British India, eventually fleeing arrest by British authorities by immigrating to America. After landing in New York in 1907, Das carried on the Indian Independence movement in exile and also married a white socialist named Mary Keatinge Morse, a co-founder of the NAACP. Morse’s marriage to Das had an unusual consequence: it revoked her citizenship. A law passed in 1922 voided citizenship for American women who married foreign men. As for Das himself, federal law had stated that only “white persons” and persons of African ancestry could be granted citizenship. Previously, attornies for Indian immigrants like Das had argued that Indians were of “Aryan descent” and therefore “whites” eligible for citizenship. But a 1923 Supreme Court decision (United States vs. Bhagat Singh Thind) voided all citizenships granted to Indian migrants by declaring them non-white. It was not until 1946 that US immigration law finally allowed Indian-born migrants to become citizens without having to resort to redefinitions of race.

This means that prior to the 1923 ruling, Das had stayed in the United States by virtue of a presumed “white” identity (how actively he framed himself as such, if at all, is not clear). Given his particular history as an anti-Imperialist activist, why did Taraknath Das not protest an unjust citizenship law that had granted him temporary refuge as a “white” person? Was it something Das accepted for the expediency of having a safe organizing base against British colonialism? Was it only a banal clerical error?

Taraknath Das floated as a pale ghost at the edge of my mind during my first reading of Vivek Bald’s first book, Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. Published last month, the book attempts a new teleology of South Asian migration to America, with Bengalis, from today’s Bangladesh and India’s West Bengal, as a central part of the narrative. While Bald’s book does not feature Das, the movements of early South Asian migrants that he documents indicate a particular decision point. Did these early migrants accept misidentification for the sake of naturalization (like Das), or did they live a life that challenged and confounded color barriers?

The book’s most valuable intervention is in how it expands ideas of race, especially the relationship between Asian migrants and “blackness.” These migrants “horizontally assimilated,” in a process that Vijay Prashad described in Everybody was Kung Fu Fighting as new alliances of “recognition, solidarity, and safety by embracing others also oppressed…”. By conducting archival mapping of these early lives, Bald shows how early Bengali migrants shape-shifted into blackness. They lived with, and became part of, African American communities. They married Creole of Color, Puerto Rican, and African American women. They raised children who themselves straddled a line between communities of color.

An MIT professor and former musician and DJ, Vivek Bald has journeyed through the archives of American migration and yielded an alternate history of South Asian Americans’ relation to race. Bald demonstrates that some of the earliest South Asian migrants to America were Bengali Muslims who settled in the American South, Northeast, and industrial Midwest. Instead of a broken migration history that restarted after the United States opened immigration in 1965, South Asian migrants–naturalized and undocumented, in the shadows and in public–form a deeper, more continuous migration history since the nineteenth century. Bald uncovers not just a hidden chapter of American history, he also models a new way to imagine what it means to be Asian American in the United States.

Piecing together a lost history

The subject of Bengali Harlem is the early Bengali migrants who made lives in America, living within the country’s Black communities on the other side of the Jim Crow line. Bengali Harlem begins with a discussion of the dual track pursued in two immigration appeals, that of J.J. Singh and Mubarek Ali Khan. Both men emphasized the accomplishments of “leading” Indian Americans, while skirting around the significant proportion of Indian American farm and factory workers. Bald contrasts their cases with the more assertive approach taken by a Bengali migrant from New York, Ibrahim Choudry. In a 1946 immigration hearing, Choudry submitted a letter that read: “I talk for those of our men who, in factory and field, in all sections of American industry, work side by side with their fellow American workers… We have married here; our children have been born here.” Singh and Khan presented Asian migrants as a quietly striving community that would not cause friction—they advocated a proto-model minority vision. Choudry, by contrast, insisted that migration was not a gift but a right, earned by past contributions and possible future roles. It is Choudry’s argument—the idea that these migrants built America—that the book also explores through the life stories.

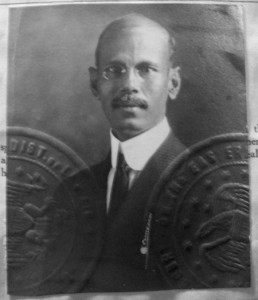

French Lick, IN), U.S. National Archives

Bald subtitles his book “lost histories,” and his research notes give us clues as to why these stories remained obscured for so long. Many of these early migrants were illiterate, and for the most part they left few written records in America. For example, a letter is reproduced in the book from the U.S. National Archives, but it is from a migrant’s wife back in British India, asking him to return from America. Missing are his letters replying to her, which would help piece together his life in America.The book’s signal achievement is overcoming this paucity of archives to trace these missing stories. Bald employed a mode akin to an archeological dig, tracking down a Bengali name from an immigrant arrival document (or in some cases, an immigration detention log), and then finding that same name a few years later in a census record of a Southern or Eastern Seaboard city. Sometimes, the names appear again in logs for marriages, usually to Black and Creole women. The search is made more complex by the crazy-quilt of Anglicized spellings of Muslim names—names belonging to men who, before leaving their country, might not have needed to spell anything in English. “Ali” is one of the common names and is spelled “Ally,” “Alley,” and “Alli.” “Miah” becomes “Meah” in a Life magazine feature. “Mollah” becomes “Molar” in a New Orleans marriage certificate. Other unusual spellings include “Goffer” (Gaffar or Gofur), “Solomon” (Suleiman), “Seconder” (Sikander), “Caramath” (Keramat), “Abdeen” (Abedin), “Rub” (Rob or Rab), and “Rohfman” (Rahman).

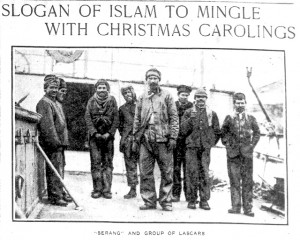

Many of these men eventually integrated into historically black neighborhoods in Baltimore, New Orleans, Detroit, and the Harlem of the book’s title. Although many of the migrants were Muslim, most from East Bengal, their affiliations extended beyond their linguistic, regional and religious bonds and they married women who were Puerto Rican, African American and West Indian. They were not legible as South Asian migrants in the classic “ethnic enclave” manner, in which the immigrant community becomes its own niche community—a “Chinatown” or a “Little Bangladesh.” And when their biracial children married into local communities of color, the Asian migrant trail was further obscured. These migrants’ identity as Asian immigrants grew mixed with other, second generation stories. Bald, for example, includes the name “Frank Carey Osborn” on one of the lists of marriages in the book. I found myself puzzled by this incusion until I realized that Osborn had married Nofossu Ella Abdeen in 1914. Abdeen was herself the biracial child of a Bengali father (Jainal Abdeen) and a Creole mother (Florence Perez), who married in 1893. Bengali Harlem maintains a delicate balancing act, combining marriage certificates, rare newspaper reports (with headlines such as “Slogans of Islam to mingle with Christmas Carolings”), oral recollections from surviving children and grandchildren, reconstruction and detective work.

Between “Hindoo” and “Negro”

Because legal migration was difficult, the early migrants arrived via many circuitous processes. These migration chains offer insights into the relationship between the dying British Empire and the newly surging United States. Changes to the Indian economy under the British caused mass dislocations. These displaced men moved first to the colonial hubs of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, and then finally abroad. Meanwhile, British ships needed ever more low-wage Indian seamen or lascars, as they transitioned to steam power in the late nineteenth century. As British ships fanned out all over the world, many Indian seamen jumped ship to leave their indenture-like conditions. These men engaged in what Bald calls a “complex calculus” of ship-jumping. They left the ship in places where there were both strong networks of other ship-jumpers and receptive local economies. Many of the seamen left their ships at Eastern ports, such as New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia, and made their way to factories in Detroit, Bethlehem, and Lackawanna.

What race were these Asian migrants? Other Americans often understood them as some variation of “Oriental.” Whether jumping ship or coming as small traders, many Bengali migrants adopted a profession that added to a particular racial identification. Many became merchants who capitalized on fin de siècle America’s obsession with the “exotic East,” which was itself an emulation of Europe’s “sophisticated” classes’ Orientalist obsessions. Here, Bald tracks a merchant network through the U.S. South called the chikondar network, linked to a delicate handicraft work known as chikon. The book teases out several ironies at play here. Many Bengali small traders had to leave British India when England began to import cheap fabrics, collapsing the domestic textile and hand weaving industries. Yet now similar products could be sold in America to feed an increasing hunger for the “sophistication” associated with “eastern” goods, whether in the home (“shawls and table cloths”) or the brothel (“afghan spreads, [and] oriental, deep-pile rugs”). Forced to play into orientalist expectations, these Bengali Muslim men acted out a particular archetype of the exotic “Hindoo” (an archaic way of referring to people from the subcontinent). The migrants may have possessed an element of knowing self-satire as well. Bald quotes one irritable reporter musing that the Indian peddlers must be “laughing in their sleeves… as they are loading us up with their ridiculous rugs.”

And yet these Asian immigrants inhabited a nether zone and confused the forces of segregation, which did not know how to classify “in-between” people. Bengali migrant’s skin tones were classified by every shade: “Mulatto” and “White” in a 1900 census; “dark,” “copper,” and “ruddy” in a 1910 passport application processing; “Black,” “Oriental,” “Turkish” or “Malaysian” during the draft registration of the first World War. This shape-shifting sometimes went both ways. Some African Americans began to pretend to be “Hindoo” and cross the lines of segregation. Thus, a black man named Joseph Downing played a spiritualist named “Joveddah de Rajah” in the 1900s. Another African American man, the Reverend Jesse Routte, traveled in the deep south without being accosted, because he had taken to wearing a velveteen robe and a turban. Activist Mary Church Terrell tells a similar story, in her book A Colored Woman in a White World, of an African American who travels with an exposition through Charleston as a “Hindu Fakir.”

We can consider these moments accomplishing a double-masquerade. Muslim Asian men played the “Hindoo” peddler, and were then impersonated in turn by African Americans. The story of a man named Bahadour Ali offers an interesting reversal of these stories. The son of a Bengali father and an African-American mother, Bahadour embraced blackness as his primary identity, taking on the name Bardu Ali and performing in the 1920s black vaudeville circuit. Bald’s central research throughout the book is concerned with how Bengali migrants interacted with blackness and the largely black communities that became their home and family, as well as white America. Regarding the latter space, for a limited time, being oriental “exotics” allowed these Asian peddlers to travel more freely within lynching-era America. Consider by contrast that wistful moment when Dubois considers his old hometown, “Thus sadly musing, I rode to Nashville in the Jim Crow Car.”

Shape shifting did not always work of course. Bald tells the story of a man named Abdul Fara, beaten by a World War I veteran for daring to sit in the “white” section of a segregated streetcar. In New Orleans, Anglo-Americans mounted a counterattack against newly empowered people of color. They segregated the city by force, flattening the heterogeneous population into a binary of black and white zones. In this volatile racial order, Asian men were categorized as “so dark as to be taken easily for Negroes” in a 1900 newspaper story about Asians in New York sailors’ quarters. The same newspaper described them as “peacable and orderly up to a certain point and then they lose all self-control and generally resort to the knife.” In other words, these Asian migrants were now considered both “inscrutable” Asians and “criminal” African Americans.

Unlike Bhagat Singh Thind, the man who argued to the Supreme Court that he was white, these Asian immigrants did not automatically identify with “whiteness.” Instead, as racial lines hardened, Asian migrants married into and lived alongside African-American families and effectively became “black.” First, some of these migrants became radicalized after experiencing anti-black racism and witnessing black anti-racist organizing, as Bald shows through the biography of activist Dada Amir Haider Khan. Second, many also became racialized through the new black nationalism of Islam. One thinks, for example, of the Ahmadiyya mission (discussed in Richard Brent Turner’s Islam in the African-American Experience), the missionary group from India that converted many African Americans to Islam—long before the rise of the NOI. Third, the black press reciprocated these bonds of warmth and sympathetically presented the struggles of Asian seamen and migrants. In contrast to the xenophobic New Orleans paper mentioned above, the Baltimore Afro-American wrote in 1925: “East Indian Sailors Strike for Grub.” Finally, Bengali men developed a reputation for being “good husbands” among some African American and Latina women. These women of color formed the crucial stabilizing element in Bald’s narrative, providing homes, boarding houses, support, and partnership to men building new lives in uncertain times and a hostile environment.

In contemporary migrant narratives, we have lost these overlapping stories between immigrants and slave descendants, in favor of the flattening narratives of “Asians in America.” Bengali Harlem destabilizes the assimilationist model minority myth, and Bald’s work is the first of many necessary steps toward constructing a new history.

A coda and a memory

LA), U.S. National Archives

Vivek Bald ends his book with a thoughtful coda focused on the playwright Alaudin Ullah, whose father Habib was a beginning point for Bald’s research. Alaudin has explored his family’s stories for his one-man show Dishwasher Dreams and the play Halal Brothers. For many years, he has been searching for a dimly remembered family photograph. It is a photograph of Ibrahim Choudry, the same Bengali man we discussed at the start of this essay, standing with Malcolm X, surrounded by African American and South Asian Muslims. By now, the photograph has acquired a mythical status, one possible missing link that establishes Bengali migrants standing at a crucial juncture of Black American history. Alaudin is still hoping to find that photograph one day.

The story reminds me of a photograph and a memory I have of Vivek Bald himself. It is a photograph I took of Bald, about to go onstage to perform as an opening act for the drum and bass artist Roni Size at Central Park. That mega-concert in 2000 marked a high point for Mutiny, an Asian underground music event that Bald had cofounded with DJ Rekha in 1990s New York. When Mutiny first began, South Asian events happened mainly at the energized margins of the city. Mutiny helped move all that to the center. By bringing British Asian bands to New York—including groups with Bangladeshi members such as Asian Dub Foundation, State of Bengal, and Joi—Mutiny shook up the model minority ethos through deeply politicized musical events. In this way we encountered a generation of British Asians, influenced by thinkers such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall, who identified as “Black British” in solidarity with Britain’s other communities of color. In a New York where South Asians were starting to enter anti-racist coalitions, such as the Amadou Diallo campaign, the concept of Black Asians created an important space for solidarity work.

In the last two decades, the city’s South Asian community has changed significantly. Bolstered by a new wave of immigration, South Asian migrants gained the scale of numbers to encourage organizations to form along national South Asian lines (say, “Indian” or “Pakistani”), rather than cross-racial ones. Bangladeshis were the fastest growing migrant group in New York for the ten years after 2001 and these numbers have allowed the Bangladeshi community to become a nationalist one. Bangladeshi-Americans now have a low level of interracial marriage— an ironic contrast with their predecessors, who married into and lived with other communties of color. In addition, an increasing Indo-centrism, twinned with the triumphalist “India Shining” bug, crowds out recognition of South Asians who are not Indian—like Sri Lankan, Nepalese, Burmese, and other migrant groups. Without cross-racial solidarity, Asian migrants may cut themselves off from the possibility of generative, progressive alliances with other racial justice movements.

Nowadays, you can sense a palpable desire to highlight white-collar South Asian success, sidelining the working class population that was the bulk of post-‘80s migration. Vijay Prashad warned about exactly these tendencies, when he responded to Dubois’s famous question “How does it feel to be a problem?” by asking South Asian Americans: “How does it feel to be a solution?” Prashad argued, in The Karma of Brown Folk, that by embracing the model minority myth in their own self-presentation, Asian Americans allowed themselves to be pitted against African Americans. In this narrative, Asians could be the exceptional minority, the one that purportedly disproved racism in America simply by “working hard.” Of course, the position of South Asians in America has gone through new realignments and reversals as a racially profiled population after 9/11, but triumphalist celebrations of “South Asian” identity can still unmoor us from longer span, shared histories.

Bald quotes poet Edouard Glissant at the beginning of the book. I finished the book thinking of another set of Glissant’s words: “We are not prompted solely by the defining of our identities but by their relation to everything possible as well– the mutual mutations generated in this interplay of relations.” In other words, many possible futures lie ahead. That day in Central Park in 2000, I stood in the audience watching Vivek Bald perform, spinning new records on the turntables. It was an exciting day, but I also wondered if mainstream visibility would end up diluting a progressive, pan-race political moment. As we have seen in the past, the seduction of mainstream “acceptance” always subtly demands that we leave something, or someone, behind. Bengali Harlem helps to imagine possibile other paths out of the cul de sac of narrowly defined race lines and lives. The stories of South Asian migrants who integrated into historically black neighborhoods of Treme, Black Bottom, West Baltimore, and Harlem speaks to other possibilities of Afro-Asian solidarity that still wait to be shaped.

____

Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America is available from Harvard University Press.

Bald and Ullah are collaborating on a documentary film entitled In Search of Bengali Harlem.

Ullah will be performing his one-man show, “Dishwasher Dreams” Feb 15-17. He is also raising funds for a longer run in New York City.

On April 6: A special event at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture co-sponsored by AAWW and the afro-latin@ forum celebrating the release of Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America.