As I celebrate Meena Alexander’s life, and revisit her books, I’m acutely aware of my mistaken impression that there would be so much more time in the future to get to know one another better.

May 10, 2019

The following is part of a series of essays and reflections published on The Margins in remembrance of the life and work of poet and scholar Meena Alexander, who passed away on November 21, 2018.

In the spring of 2014 I enrolled as a visiting student in a class at The Graduate Center, CUNY called “Partition, Migration, Memory” taught by Meena Alexander. At the time I was an MFA candidate in fiction writing at Hunter College, eager to fulfill my one remaining literature class requirement. But there were other reasons that I desperately wanted to study with Meena.

In Meena’s book Fault Lines, originally published in 1993, I had read: “And what of all the cities and small towns and villages I have lived in since birth: Allahabad, Tiruvella, Kozencheri, Pune, Delhi, Hyderabad, all within the boundaries of India; Khartoum in the Sudan; Nottingham in Britain; and now this island of Manhattan? How should I spell out these fragments of a broken geography?” In Meena’s writing I had recognized some of the central questions of my mother’s and grandmother’s lives—and of my own too.

In Meena’s seminar I was an avid student but also an underprepared one; I hadn’t read or discussed literary theory since my undergraduate days. In the first classes I watched, staying quiet as Meena’s PhD students dissected some of the dense, theoretical readings she had assigned and related them to our discussions of Partition. Around her large table we discussed Jacques Derrida, Frantz Fanon, Arjun Appadurai, Kamala Das, Merleau-Ponty. Meena delighted in the enthusiasm and effort of her students, and she often stood up when a particular question excited her to chart her ideas on the blackboard, swaying, close to dancing, with the force of her ideas. That spring, the lilt and authority of Meena’s voice burrowed into my subconscious and set up root.

It was not typical for fiction writing students to take Meena’s graduate seminars, but there were three of us that semester—Swati Khurana, Meng Jin, and myself. Meena seemed delighted to have us in the classroom, often calling on us to comment on how our discussions might be applied to the study of fiction. As the semester progressed Meena gave me the confidence to speak more often, asking me to relate our classwork to my experiences in Pakistan. I wrote papers that drew on my readings of Pakistani authors— Saadat Hasan Manto, Qurratulain Hyder, Ismat Chughtai—to consider how the city of Karachi has been represented in post-Partition literature as a site of trauma, exile and reinvention. Meena encouraged me to look again at the work of Fahmida Riaz, commenting on my proposal for a paper: “Important to bring in the themes of identity and its rupture and also the question of gender—the historical gap between Partition writing and work that came decades later. Some of the trauma theory materials might be useful.” We spoke during her office hours about my interest in fragments, phantom limbs, false memories—concepts that I had been drawn to in our weekly readings. I noticed with surprise and interest that ideas from her class were beginning to enter my fiction writing, and I gave her some of my pages to look over. “Fragments!” she exclaimed when she received them, smiling and running her hands over my short paragraphs.

In early summer, Meena invited my family and I for dinner, and my husband and I were fortunate to spend an evening talking with Meena and her husband, historian David Lelyveld, about teaching, writing, parenting and how to make a life split between New York and South Asia. Meena seemed genuinely disappointed that we hadn’t brought our then eighteen-month-old daughter along—I realized that she was that rare teacher who didn’t merely tolerate but enjoyed the fact that some of her graduate students were also parents. Towards the end of the night Meena pulled me aside to show me her book-filled writing nook. She told me about her children’s accomplishments and interests with pride, describing how raising them in New York had informed and enriched her life and writing. She asked me to bring my daughter Noor Jehan to play on the playground across from her home sometime and encouraged me to bring her to the Cloisters. “Children love the unicorn tapestries,” she told me. Her eyes seemed illuminated with the memory of taking her own kids there when they were small.

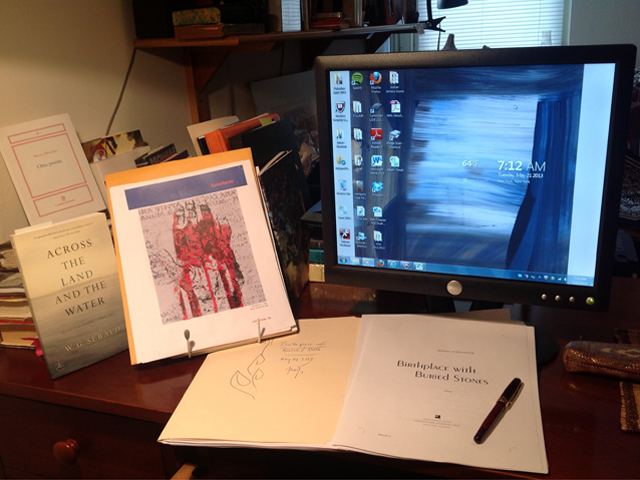

The following spring I returned to Hunter College to teach creative writing. I remembered that Meena had told me that she rarely used her office on the twelfth floor, as she was so busy at The Graduate Center. So I was surprised one evening to notice the light on in her office, her door open wide. I popped my head in the door and saw her jotting down notes in a notebook with an embroidered cover. She might have been using a fountain pen. I asked if I was bothering her and she said: “Oh not at all, come in! I had some time today so I thought I’d walk across the park and come here to write some poems.” She said this so matter of factly, as if all that she needed to write was a free afternoon. It all seemed effortless—the flow of her script on the paper a pleasure. So different from my own, angst-ridden process! I sat down, doing an impression of the screwed up, anxious posture I inevitably fell into when I wrote fiction. This made her laugh her full-throated, musical laugh. “You’re funny!” she exclaimed. “I didn’t know that! Tell me more about what you’re working on these days.” We spoke again about family and writing, about India and Pakistan and New York. She suggested that we meet for a drink sometime. There was a bar she liked near The Graduate Center. The place would be especially appropriate, she told me, because we had read Derrida together; this bar was called The Archive.

We last corresponded in early 2018, after she read my short story in The New Yorker and sent me a note to say “Mabruk.” In her next message she shared some thoughts on the story. A few weeks later I sent her a note to congratulate her on her poem “Kochi by the Sea” which appeared in the same magazine. She told me that she was undergoing chemotherapy. She mentioned the uncertainty of what the future might bring. But she also wrote about the books she was writing and her plans for their upcoming releases. I had the impression that her most vital work was ahead of her. I wished her well in her treatment and her writing, telling her how much I looked forward to catching up with her when things settled down. And then, a few months later, she was gone.

As I celebrate Meena’s life, and revisit her books, I’m acutely aware of my mistaken impression that there would be so much more time in the future to get to know one another better. I always told myself that I would get back in touch with her again soon, that she was busy, that I shouldn’t bother her, that she had so many other closer students and friends that she needed to make time for.

In her absence, I return to the ideas of fragmentation we discussed in her class and which reappear in her work—the split of the subcontinent, the scatter caused by multiple migrations, the desire to knit a self together. How do we understand and honor the fractured histories that have formed us while forging something whole and new? Meena wrote: “I sit here writing, for I know that time does not come fluid and whole into my trembling hands. All that is here comes piecemeal, though sometimes the joints have fallen into place miraculously, as if the heavens had opened and mango trees had fruited in the rough asphalt of upper Broadway.”

As I write, I think about the easy scratch of her fountain pen—for yes, it must have been a fountain pen, I can see it now—and about how much Meena seemed to relish the coexistence of her writing, her family life, and her life as a scholar. She seemed to inhabit each of her worlds joyously and without reservation. The greatest lesson she had to teach me was the generosity she brought to each.