Men are standing side by side with women in the struggle

to stop domestic violence and toxic masculinity.

November 8, 2018

Against a backdrop of Bengali folk dancers, bhangra dance lessons and panipuri-eating contests, a handful of men in their twenties approached other South Asian men, of different builds, sizes and ages. Cautiously, they asked the men if they wanted to talk about uncomfortable topics: street harassment, domestic violence, and masculinity — conversations that sometimes are brushed aside in traditional South Asian spaces.

The exchanges happened on 77th Street in Jackson Heights, where the annual Chatpati Mela street fair took place on July 21. But they have been happening elsewhere, too: at parades, town halls and other public gatherings.

Chhaya CDC, the sponsors of the fair, intend it as an annual gathering of South Asian arts and non-profits organizations. It is filled with familiar conversations between providers, neighbors and nonprofits. But the crowd, brimming with families as well as those who wandered in by chance, was also a stage for new conversations that haven’t been happening.

“How can we go about tackling patriarchy, hetero-patriarchy particularly, and how are we going to engage other men in the community?”

“Can we speak to you for a minute,” one of the young men asks, handing out a printed postcard-sized flyer with information about domestic violence.

The men are part of a Men’s Eckshate – from a Bengali word meaning “togetherness” – organized by Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) for the purpose of reimagining masculinity in society and ending gender-based oppression.

“It’s more folks engaging each other in terms of thinking differently about manhood, what healthy manhood can look like,” says Will Depoo, the gender justice organizer at DRUM who leads the Men’s Eckshate.

“How can we go about tackling patriarchy, hetero-patriarchy particularly, and how are we going to engage other men in the community?” he says of the conversations he guides with Eckshate participants.

Gender-based violence has long been a stress-point in New York City’s South Asian communities, exacerbated when external tensions like poverty and immigration status mount, unthreading male egos.

In some communities, harassment, catcalling, domestic violence, and alcoholism are constants.

***

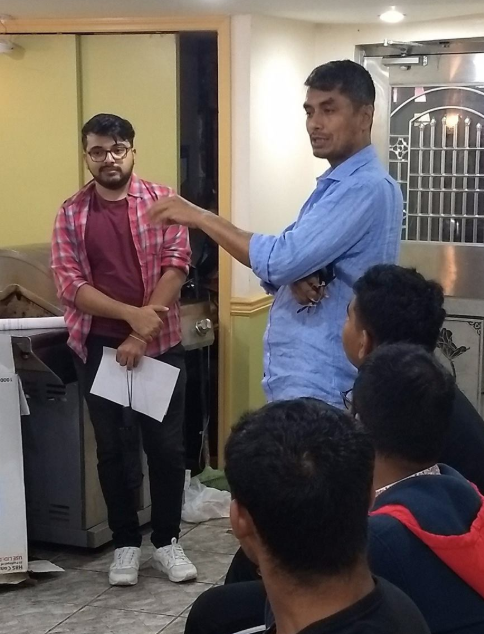

Photo courtesy of DRUM’s Facebook page.

Domestic Violence Murder

Recent tragedies have put the problem in sharper focus, most prominently the January murder of Indo-Caribbean woman Stacey Singh, which sent waves through New York City’s South Asian communities.

The response to the problem over the years has come in the form of non-profit advocacy, like that of Sakhi for South Asian Women, or grassroots education, as with the Jahajee Sisters organization for Indo-Caribbean women. These organizations are led and mostly staffed by women, who are essentially forced to do the bulk of the labor to facilitate healing in women and educate men.

But some men are also taking up the work, perhaps a sign of a larger cultural shift. Advocates see it as necessary not just to lighten the burden on women doing DV work — many of whom are themselves survivors of various types of abuse – but because men causing harm are more likely to accept advice from other men.

“I wish this wasn’t the case, but often the messenger really matters,” says Shivana Jorawar of the Indo-Caribbean gender justice group Jahajee Sisters, referring to the Men’s Eckshate group.

“If it’s me, a woman, speaking to that kind of person, I might just be dismissed,” Jorawar said.

DRUM has been holding the Eckshate’s weekly meetings for a select group of men in their membership since April of this year. The program is intended for men to build deeper relationships, interrogate how they’ve been taught masculinity, and develop an analysis that can help them dissolve patriarchal norms and end gender-based violence.

The goal is for participants to go out into their respective communities and begin dialogues about masculinity, trauma, and the safety of women in public spaces.

The group spun out of a similar program for young women that DRUM began two years ago, spearheaded by member Jensine Reihan. Reihan developed a Women’s Eckshate program as a space for young women to talk about gender oppression and street harassment in schools.

The young women in the program began thinking about how men could better shoulder the burden and be supportive to women in the community in more concrete ways. That led to a new position at DRUM – gender justice coordinator – with Will Depoo filling up the role.

Depoo says he spent a year researching similar works being done by organizations across the country. They include Man Forward, a Southeast Asian men’s group, and “Khmer Girls In Action,” a grassroots organization for young Cambodian women based in Long Beach, California.

With 12 participants ranging in age from 17-50, the Men’s Ecskhate is multi-generational and diverse in language and nationality, pulling from a variety of people in DRUM’s membership. Participants have different levels of familiarity with gender justice; some have been engaging with the work since they were teens, some older members came in with little awareness about gender equality.

But all were driven to the program by witnessing painful realities of South Asian women. To many, that meant feeling the impact of domestic violence in their extended families. The problem, advocates say, is rampant, especially in poor and working class communities: two in five South Asian women in the U.S. are survivors of reported acts of domestic violence, according to CDC data.

***

Healing From Trauma

The first group of Eckshate participants met three times a week for three months, with sessions lasting about two hours each.

As each meeting opened, the group of a dozen men sat in a circle in DRUM’s Jackson Heights offices. The men start with introductions, stating their names and gender pronouns, then move on to the different topics of the day, tackling different aspect of masculinity. Through paired conversations they open up about narratives they’ve inherited about what it means to be a man.

The culmination is an anti-street harassment campaign, developed by the members of the Eckshate, with the goal of doing outreach in public gatherings. But before this happens, there is a lot of talking: deeper conversations meant to address traumas and imagine a healthy version of manhood, Depoo says.

“I’ve experienced a lot of discrimination in my family, a lot of it rooted in toxic masculinity.”

“How do we be emotional, and open, and vulnerable folks, how do we develop our emotional intelligence?” Depoo asks, adding that the Eckshate focuses on the sublimated pain that is the root of male anger. He said it is important to learn how trauma impacts behaviors, and how it affects the way men interact with women, queer and trans folks.

For some members, that means a gradual realization that unhealthy concepts of masculinity may have made them feel alienated while shaping their self-perception.

Sadat Iqbal, a 31-year-old DACA recipient who is a member of the Men’s Eckshate, had even more difficulty navigating masculine spaces as a gay man.

“I’ve experienced a lot of discrimination in my family, a lot of it rooted in toxic masculinity,” Iqbal says. Those experiences were the source of a lot of pain within his Bangladeshi Muslim community, he says, and something that caused him to avoid South Asian spaces growing up.

He cites several experiences that pushed him to address misogyny in his community. Though arranged marriages are fairly common in South Asian communities, even among first- and second-generation South Asians, he saw how skewed the power balance was in some of these relationships.

When his brother got married, Iqbal says, his new sister-in-law was heartened that her new husband did not push her to have sex when she wasn’t ready. This struck Iqbal and made him reflect on what had been expected of other women in his family.

“It blew me away and broke my heart,” he says of the story. “The reality is you (women) get raped on your wedding night.”

He began thinking about how to navigate marriage in Bengali culture, wondering how much agency or choice his female cousins had within their relationships, what he could do to support them. As the only queer man in the group, there were challenging moments, he says. Some of the older members of the Eckshate criticized his sexual orientation, launching into religious arguments that reminded him of the oppression he had faced growing up.

“They basically proselytized me with Islam, and these were the kinds of things, reasons why I had stayed away from the South Asian community for quite some time,” Iqbal says. But he engaged with them and they listened, although he’s not sure if he was able to change their minds.

“Part of this was to work this through on a personal level, but also to use these experiences to think about the ways they’re ‘othering’ their own brothers and sister, whether they’re women or men,” Iqbal says.

***

Common Threads: Male Anger

Throughout the sessions, some common threads became clear, among them a temper that manifests in South Asian immigrant men.

Nilesh Vishwasrao, 24, says he was one of the more politically aware in the group, having had an interest in gender justice from the time he was a teenager. But years of witnessing domestic violence in his community – he grew up in Jackson Heights, his family is from Mumbai – led him to the Eckshate in his search to find ways to confront it.

Vishwasrao told me he witnessed lots of male anger growing up, but he never was able to put it into context until he started spending time with white friends and realized how different their family lives were from his own. It was something he saw that was reflected in the lives of his friends of color as well.

“The commonality we had was how scared we were of our father figures,” he says. “When I would go to white people’s houses, this wasn’t as big of an issue.”

The issue of anger gave Vishwasrao pause during some of the actions: how angry could a person like that get, he wondered, when confronted in public about street harassment or domestic violence?

“Misogyny and trauma may have long histories in South Asian cultures, but all the Eckshate participants said they had seen male anger in their communities flare up since the 2016 election.”

“They were told the man of the house had these rights over everybody else, over the women, over the children,” Vishwasrao says. He found it difficult to visualize a change of behavior for elders in the community where these behaviors had become ingrained.

“Trying to unscramble that and get them to unlearn that, I’ve never seen it happen with an older person in the community,” he says.

Many gender norms in the community are more hardened among older members, but Eckshate participants said a generational divide shouldn’t be over-emphasized, and that misogynist behavior is more than apparent in first- and second-generation South Asians.

“I think one interesting thing is how, as younger men, we assign a lot of blame for toxic masculinity on older men, and absolve ourselves of how we participate and enact it as well,” Iqbal says.

He recounts that sometimes before the meetings, some of the members would catch themselves talking about women and would try to hold one another accountable. “It’s one thing to talk about this while you’re in a workshop class, but to really internalize it and think through how you live and breathe that and support each other, it takes work,” Iqbal says.

***

Class and Immigration Status and a Solution Beyond Policing

Misogyny and trauma may have long histories in South Asian cultures, but all the Eckshate participants said they had seen male anger in their communities flare up since the 2016 election. High-profile Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids, renewed scrutiny of immigration status, and a spike in deportations are all having an impact on the psyche of their communities, they say. And the brunt of this frustration is unloaded onto immigrant women.

Iqbal has seen first-hand how immigration status can trigger male anger. An extended family member is married to a DACA recipient whose father is in deportation proceedings. He says the deportation proceedings have created tension in the relationship, and family members are noticing signs of intimate partner violence. Iqbal became concerned when he overheard her being yelled at over the phone.

“We’ve been trying to keep the lines of communication open and make sure that she knows that we’re here for her,” he says.

“Domestic violence is a very real thing in our community, and I think as our communities are increasingly under attack, it’s flaring up a lot.”

“How are we creating community alternatives to prisons? When people commit these heinous acts, how do we allow people to understand their trauma and take on working with other folks?”

But DRUM’s Depoo says it’s important to find grassroots solutions to these problems, rather than pushing for policy solutions that rely on criminalization. The emphasis on outreach at public events is rooted in this mission. Depoo says their outreach strategies took inspiration from other organizations like Brooklyn Movement Center, an African-American-led grassroots organization, that runs an anti-street harassment campaign in in Central Brooklyn. The group’s emphasis on community-level outreach, including visiting neighborhood barbershops, was something Depoo found important.

Brooklyn Movement Center’s anti-street harassment work is focused on finding solutions outside the criminal justice system. The group states on its website: “We are committed to developing alternatives to police and state intervention in matters of combating street harassment in Central Brooklyn.”

It’s a value that Depoo shares and hopes is reflected in DRUM’s work, which is focused on poor and working-class communities, whose undocumented residents could face extreme consequences, including deportation, as a result of criminalization.

“How are we creating community alternatives to prisons? When people commit these heinous acts, how do we allow people to understand their trauma and take on working with other folks?” Depoo asks.

He says long-term work has to be trauma-informed and survivor-informed, meaning that the work has to be centered on healing the underlying wounds that underpin harm, and centering the needs of those harmed. He says the programming is a better fit for communities than sending sometimes-traumatized people to prison, where, he says, “they end up worse,” upon release.

***

Tension and Impact

The first Eckshate “class” culminated in an anti-street harassment campaign, to be realized at large outdoor gatherings. The first of these was at the Phagwah Parade, a yearly celebration of the Holi holiday for the Indo-Caribbean community in Richmond Hill. The annual parade brings drummers, floats baring the names of local temples, dancers, and plumes of purple-colored powder down the path of Liberty Avenue. The event has also been a site of street harassment, as in many of the city’s large gatherings. It’s one of the reasons Depoo, who is Indo-Caribbean, sought the space out.

Depoo and Iqbal say there was an awkward reception at the event: the Men’s Eckshate had been campaigning alongside and in solidarity with the Caribbean Equality Project, an organization focused on queer Caribbeans. Some men at the parade whom they tried to approach assumed the Eckshate and Caribbean Equality Project were connected, Iqbal says, and lingering homophobia led to dismissive looks. Still, Depoo says, some were receptive, and the event was a good starting point for more work.

On September 8, DRUM held a Dhaba, or community-café, a workshop aimed at addressing street harassment in the neighborhood. DRUM says participants, about 30 men in the community, committed to intervening when they see harassment and to hold more actions in the future.

After the Dhaba, the Men’s Eckshate held a “graduation” ceremony, where participants received a certificate of recognition. DRUM posted a Facebook post of the event, saying, “This doesn’t mean their work ends. Men’s Eckshate is planning similar actions in all our bases, and working towards ending gender oppression.”

Though members of the Eckshate only knew one another in passing beforehand, they say the meetings have changed their perspective. And in the long run, DRUM and the men of the Eckshate hope that it could lead to a radical shift of the gender norms that underpin violence against women, queer and trans people.

It may take generations, Iqbal says, but, “these individual choices that we make, they add up.”