Writers Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Violet Kupersmith, and T Kira Madden speak to each other about mixed-race identities in life and literature

June 16, 2017

February 28 isn’t too cold. I hurry through sharp sunlight to a café in Lincoln Center. It is the official launch day of my novel, Harmless Like You, in the USA. I feel woozy and anxious. I’ve been avoiding bookshops, because I’m too scared to know if it’s in stock. I’m meeting two dear friends who are also writers. T Kira Madden is the Editor in Chief of No Tokens Journal, with her memoir forthcoming. Violet Kupersmith’s collection of stories The Frangipani Hotel was published by Speigel & Grau, and her novel is forthcoming. They are both dear friends of mine, and it has been too long since I’ve seen their faces. The other thing we have in common is that we are mixed-race. Specifically, we have one Asian parent and one white parent. I’ve been told that equals accessible exotic. I want to ask Violet and Kira how they deal with this and how it affects them as writers.

— Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan: I never know what to call myself. At readings, people laugh at me when I get introduced as British-Japanese-Chinese-American, like it’s a punchline. I think, hey it’s not a joke. But I laugh too because I’m nervous. In Japan, I called myself hafu which is the accepted word there. I know lots of Americans say hapa—but I’m nervous about my right to take something from Hawaiian Islander culture. I grew up saying halfie, which I worry is too cute—but it is at least mine. So these days, I go back to halfie.

Violet Kupersmith: I’m half-Vietnamese and half-white. My mother’s family came to America on a boat in the seventies. My father’s side is all mixed European potato genes. I remember being really excited when the term “hapa” first started getting circulated, because it was finally a real label I could apply to myself after growing up having to just check the “other” box on all my paperwork. But I still feel a little squirmy referring to myself as hapa out loud because, like you said, it’s from Hawaiian Islander culture.

T Kira Madden: I am Hawaiian so I’m used to “hapa! hapa haole!”

VK: And you can say it with confidence!

TKM: I hope so! I am native Hawaiian, Chinese, Irish, and Eastern European Jewish, which is a curious combination. My father’s father was an Irishman and his mother was an Eastern European Jew—so he was raised Jewish. I was raised with some elements of Judaism, but my mother’s side is Mormon, Buddhist, Catholic, and those who worship the Hawaiian Gods and Goddesses, so we have many languages, many belief systems, different traditions. I do feel comfortable with hapa. And it’s fun to say!

RHB: When I was young, I only knew two mixed-race people and one of those was my brother. The first time I encountered mixed-race people in literature was in manga, and they were always these blonde, blue-eyed Japanese people and everyone was always really excited that they were blonde and blue-eyed. They seemed distant from anything I knew about myself. When you were growing up did you see anything, read anything about being mixed-race?

TKM: I went to a predominantly Jewish Prep school in Boca Raton, Florida, which is essentially a retirement community. I didn’t even know the term hapa until I went to Hawaii for the first time as a child. Back home in Florida, nobody looked like me. I was one of the most visibly nonwhite people at my school, period. In a way I feel like my life is divided between the first half, in which I fought so hard to be considered white, and now, when I just want to be accepted within my Asian community. In Boca Raton, I lightened my hair. I told my mom not to get of the car at school. My father was a blue-eyed blonde; I could pass with him. Not my mother.

I didn’t have mixed-race people in my literature or in my surroundings. No way.

And my sister—well, that’s a whole other story. She’s a fellow South Floridian hapa, but I didn’t know she existed. She was adopted at birth, in the seventies, by a Jewish family—incredible people—so we grew up in the same area, with the same racial makeup and racial surroundings and the same identity confusions—it’s something we’ve bonded over now.

VK: I also grew up in a super white area—the Philadelphia suburbs. The only Asian-white mixed race figure in my life was my mother’s half-Vietnamese, half-white American friend. But her background was so different from mine—her father was a GI and she grew up in Vietnam after the war. Her very existence was political. She was subjected to really cruel bullying. Kids would punch her in the nose because the bridge was higher and more European-looking. Whereas I had a very sheltered, white upbringing. Plus fish sauce. We did eat Asian food but that was where it ended, tradition-wise. I didn’t really realize that people saw me as different until I was eight or nine and our school was hosting a group of Mexican exchange students. And at a classroom event someone’s Mom came up to me, thinking I was one of the Mexican students, and asked me How are you liking America so far? And I had to answer back like Hi! It’s me—Violet! I’ve been in your daughter’s class for two years! I think I’ve actually been to your house before! That was a real turning point where I realized—I don’t look like these other kids. I’m brown, and that’s what people see first when they look at me. The whole thing sent me on a very long identity spiral. When I eventually ended up spending three years living in Vietnam, it was the complete opposite—my American identity felt kind of lost, but was still the immediate thing that people noticed about me. I don’t think that confusion and feeling of otherness is something you ever really escape.

RHB: People like to guess my race. Am I Italian? Asian? Russian? I especially find it weird when I’m dating. I was with someone who was convinced I was Taiwanese the first time he saw me. Then, I was dating someone who was Asian American and who had known me for a while as a friend, but was completely shocked when it turned out I was mixed-race. And these people liked me. They’d seen me at close range. But they saw completely different things and that’s a very weird feeling.

VK: I feel like a human litmus test. I get mostly guesses that I’m Latina. But the other day a guy yelled at me on the subway, “Are you Arabic?”, which was new! It’s rude, but deep down the insecure part of me that never felt Asian enough is weirdly pleased to know that I register as different to strangers. And I can’t complain because I go around sneaking glances at other ethnically ambiguous people on the street and trying to figure them out, like—“You! Definitely half-Asian!”

RHB: I react totally differently though, depending on who’s asking. When you approached me, because you knew I was half, I was so excited that you were too. (This, dear reader, is how two mixed-race women made friends in a small, rather white town in the east of England.) But if it was an older man, then my response is to run away.

VK: I guess I’m just trying to recognize people like me.

RHB: When I see little kids from mixed-race families, I get really happy. It’s odd though, because you see so many more kids than adults. I know one older mixed woman, who is part Irish-American and part Japanese-American. And I guess I wonder if she’s what I’ll look like when I’m older. Because I’m not going to look like my mom and I’m not going to look like my dad.

TKM: I think the first time I felt that was in college. I came to New York City and went to Parsons School of Design, which is half international, mostly Asian. My class cliqued up a bit between the Japanese groups, the Chinese groups, the Filipinx groups, the white groups. Somehow, I ended up in this group of hapas. I didn’t even realize it until later on when I looked at the hierarchical situation there. The only friends that I left college with were this group of hapa people.

I didn’t know at that point that I was mostly Chinese—I was always raised with my Hawaiian culture, my Hawaiian family, my Hawaiian language, Hawaiian food, my Hawaiian name.

Then Rowan comes over one day and my grandma is there—my mother’s mother—and she says, “Oh, you look the same. You look alike.” And I say, “but Rowan’s Chinese.” My grandma says, “So we should talk.”

This grandma is my namesake—Mahealani. And she says, “I’m not actually Hawaiian, I’m Chinese—one hundred percent.” And she shows me our family tree, and explains that our family name is actually Ching. Her real name isn’t Mahealani Kamakawiwo’ole—it’s Yuk Jean Kam. My great-grandma’s name is Kim Lin, not “Rose.” They changed their names because, when they moved to the islands, they wanted to westernize and fit in with Hawaiian culture. My grandfather is Hawaiian and Chinese, so it turns out that I’m Chinese with just a bit of Hawaiian rather than the opposite.

RHB: Nothing quite like that happened in our family. But recently, I’ve been trying to get things in order and writing essays about family history. So I’m asking all these questions and things come out–but they’d say you can’t publish that bit. I’d say okay, but what can I say that is also true? I can see why that when you have difficult histories, you might want to keep things in the family.

Kira, you write memoir so you might have more to say on this than I do?

TKM: It’s tricky. There’s the unreliability of memory, the groupthink of memory. One person says “this is true” and then everyone agrees that it must be true. I ran into so many problems writing the book and still, there are questions. How do we honor the dead and what the dead would want? My grandfather’s dead, but I can infer the reasoning behind certain choices he made for our family and our identity and our changing names and our moving to the Mainland—I don’t want to unravel that new identity he made for himself, for his children. How do you honor the dead and also honor what’s true? How do you honor the current political landscape and what needs to be said about it? What stories need to be told and who has the right to tell them? I’m still navigating my way.

RHB: This brings us to something I wanted to ask you all. Do you think it’s important to have mixed-race people in stories? What’s important for you, if you do it or when you do it?

VK: My first book, I didn’t have a mixed-race perspective. I wrote white characters and Vietnamese characters. I was comfortable hopping back and forth between them. In my novel, I tried writing about a half-Vietnamese girl and it’s so much harder. It’s so close to me and I kept comparing it to myself and thinking other people would compare her to me. I think I was too close to get a really good perspective on her. I’m still struggling with that. It’s something I need to fix in the next draft. For me, it’s hard because of the name thing. I don’t have a Vietnamese name on paper—I’m just Violet Kupersmith. I felt a little guilty that I write from a Vietnamese perspective. I do have a Vietnamese name, but it’s not on paper. You two have middle names, what’s that like?

TKM: I wish I could use my whole name on paper, or on my book, but T Kira Mahealani Ching Madden isn’t exactly memorable.

Before recent years, I mostly wrote about white men. In grad school people asked why I was writing all these white male stories, from their point of view. It had nothing to do with my interests—it had more to do with my own sense of identity, my anxieties about who I was; am. Now I’ve written a memoir about identity and race, and my novel in progress has a hapa narrator. It wasn’t this epiphanic moment of “Now is the time to write about queer hapa women! It’s political!” It had more to do with feeling closer to my own self and history, thinking about the memory stutters and generational echoes in narrative, feeling comfortable standing up with my stories and my families’ stories that felt too distant to me before, as a passing girl in Boca Raton. Those characters are slipping into my narrative now, not because I’m more interested, but because I know more about them.

RHB: My novel, Harmless Like You, has mixed-race characters. But in short stories, I struggle. I get very anxious that if a character is mixed-race, the reader will want the whole background. If I write a half-Asian character but don’t give their family history, the reader is going to assume they’re either white or Asian, depending on the name I give them. As much as being mixed-race is very important to me, I don’t sit around going, “I’m a mixed-race person eating, I’m a mixed-race person making out.” I’m not always thinking about it. It can feel unnatural for a character stop the narration to dwell on family history. In a short story, there’s so little space so it creates an added pressure.

I made a conscious choice to use my middle name in my writer name, even though no one can pronounce it. At events, there’s often an awkward gulp before the interviewer says my middle name. But I’m grateful that they’re trying. There are lots of names I’m still learning to say.

But, I’m so glad that you guys are here. That I’m not the only one—

VK: Struggling with these questions.

RHB: But I’m so excited for the novels all those little halfie babies are going to write someday. There are so many ways to be mixed. Even amongst the three of us, our stories are so different. There are so many more stories, memoirs, and novels brimming, in writers who look nothing like us. Despite the fact that the 2015 Miss Universe Ariana Miyamoto was half-black and half-Japanese, it is often assumed that if a baby is half-Asian the other half is white. This ignores so much brilliance and diversity. I’m so excited for the halfie women who are also latina, black, Arab and the words and stories that they’re telling. There are going to be so many beautiful stories by mixed-race girls.

TKM: Yeah, and it’s like we have a superpower, really, getting to know different cultures and foods and films and stories.

RHB: And hey, at least there’s not the worry of, “Oh no, my white suburban novel has been written already.”

TKM: Yup.

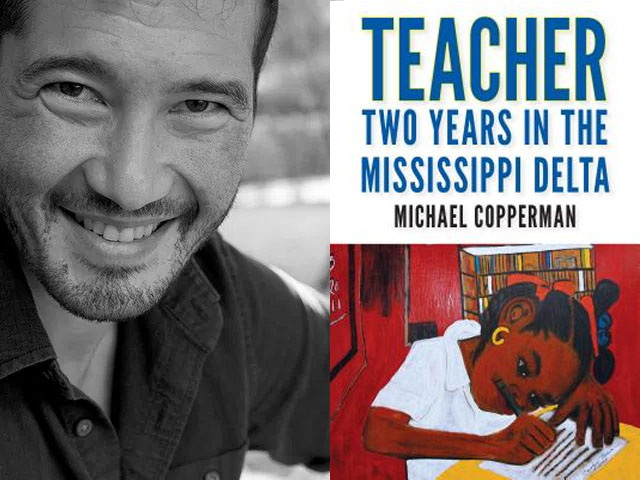

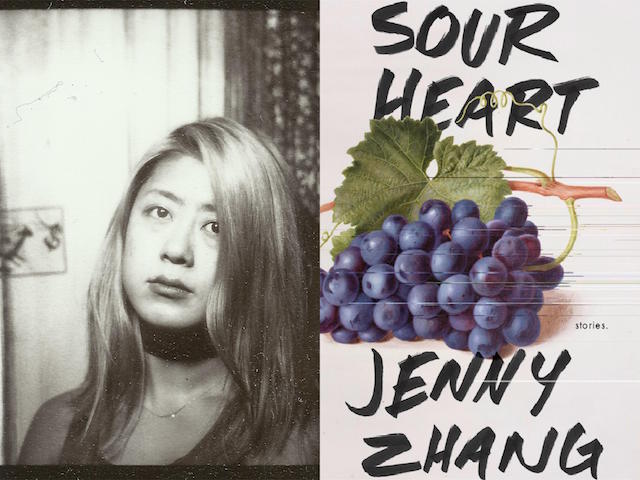

We go to the park to have our pictures taken. None of us enjoy being in front of the camera. But we do it because Emma Stone played a hapa woman in Aloha. It would have meant so much to all of us to see a mixed-race role played by a mixed-race woman. We’re not in any movie, but we’re out in the world. So we want to show our faces. It’s cold but bright, and we manage. When we say goodbye, I’m sad, but I know they have work to do and stories to write.