How does living without papers in the U.S. in the 1980s compare to today? Spoiler alert: It wasn’t that bad then.

February 12, 2018

Our favorite next-door neighbor was a woman named Terry who lived on the stoop of an abandoned building. The place had burned down before we moved in, but Terry was still there. She sat on the front stoop all day long, engulfed in a cloud of old-fashioned perfume, with layers of blush on her cheeks, hair teased into a bouffant and red lipstick that pushed past the borders of her lips. She was a large lady whose swollen, stockinged legs piqued my curiosity as a young teen.

Every time we came and went, we would say, “Hi, Terry, how are you?” and she would reliably reply, “Fine, thanks,” in an unfamiliar staccato, likely an accent from the middle of America. We knew that she didn’t like vegetables—only steak—but other than that, not much. We couldn’t get to know her too well because if she was in a mood, she would curse you out. We heard her shouting into the open air some nights. She would stand in the middle of the street, supported by those swollen legs, and just scream at someone, something. Still, she was nice and no one minded. She lived on that abandoned stoop on the Upper East Side for years.

The Upper East Side. Almost 25 years later, in 2017, I was on that same stoop where my family has lived and run a day-care for decades, when a different woman who could have been a skinny version of Terry took a seat. She was missing a few crucial teeth and was clearly in some sort of chemically-induced haze. Thinking of Terry, I politely asked her if she could move across the street because the children were about to come outside. She argued, then begrudgingly got up and left, not before she looked over her shoulder and asked, “Are you an illegal alien?”

First, I let out an undetectable gasp. Then, in perfect English, emphasizing my diction to make it all very clear: “No, ma’am. I am NOT an illegal alien.” But I was shaken. While the answer was an indignant “NO” the truth was that for many years, the answer was an unutterable “YES.”

“Everyone had documents. They are the end-all, be-all for immigrants. They are your everything. They are all you have. They are your past, your present and your future.”

The regular fusillade of anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Trump Administration has created such a nurturing environment for bigots from all manners of background that I found myself answering to a woman who did not hold the power in that exchange. We lived there. We not only didn’t call the cops on a woman who lived on the stoop many years ago, we were sensitive to her dietary desires. We didn’t kick a lady wandering in from the park off our stoop, we asked her to make room for children. But simply because reality inconvenienced her at that moment, her instinct, her entitlement, allowed her to question my existence in this country. And I balked.

So, once the Trump Administration announced that it would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in March — tossing up the lives of hundreds of thousands of people like children toss up autumn leaves — I watched with particular intensity. That could have been me. To be clear, DACA allows people who were brought here by their parents to work, study and live.

In the late 1980s, as a little girl, I thought it was a juicy little secret. I loitered at our neighborhood library almost daily and when a group of officials came to the basement to work on the Census, it felt like the right time for an adventure. I pretended not to eavesdrop. I lurked around the door, then darted back upstairs repeatedly. Looking back, they must have noticed the delusional little brown girl with a bowl cut sleuthing about. It was a mixture of fear and curiosity. I wanted to know what they were doing because we were not a part of it. I secretly wanted them to ask me about my family so I could find out how we would be counted, but I knew it was not a game. I couldn’t lie for my life, but I had no problem holding this secret. The stakes were too high.

Our family of four came to the United States from Iran in 1985, on a tourist visa. The Islamic Republic had taken power after the revolution in 1979 and by 1985 was in the middle of a brutal war with neighboring Iraq. A fresh new enemy of the U.S., families from Iran did not get tourist visas. But we did. First, we visited an aunt in London, then an uncle in Dallas, Texas. From there, they decided to stay. Dallas was not the most hospitable place at that time, and we were used to big cities where people walked the streets, so we moved in with another uncle in New York City just a few years later.

While we admittedly overstayed our welcome in America, there was still a path toward citizenship. We applied for our green card through family immediately and awaited our turn. The pathway towards legality came through what we would call a bonafide relationship today. Today meaning 2017. 2017 meaning the year I was called an illegal alien for the first time, over two decades after I shed that honorific title — whether it be illegal or resident.

And while there wasn’t an explicit law for allowing undocumented people to wait their turn on U.S. soil, as opposed to outside of it, there were loopholes that were accepted practice. And as we have all painstakingly learned in this past year, the whole system seems to run on commonly accepted loopholes.

People waiting for the behemoth machine we familiarly know as immigration to spit out their number didn’t get the boot back then. My parents had drivers’ licenses and social security cards. The cards said they were not valid for employment, but that didn’t seem to matter. They paid taxes promptly every year. My mother started a group family day-care, which was licensed through a city office. My father studied to become re-certified as a physician here in the United States. While they were able to go about their business, there were limitations and we eagerly awaited our turn.

Finally, in 1993, we got the letter. That letter. The one we had been anxiously awaiting for eight long years. We had an appointment. It had come just in time. My sister was ready to go off to college, meaning she was ready to apply for student aid. They don’t give aliens money. My father was getting close to passing his tests.

“While the conservative Ronald Reagan granted one of the largest swaths of amnesty in recent history in 1986, humanitarian loopholes were closed under the more progressive Bill Clinton.”

We had to leave the country for our appointment, which meant we also had to pay for advance parole, which is essentially government insurance. In the event we were denied green cards, we could come back to the US and start the waiting game again. Advance parole, like bonafide relationships, is also on the chopping block now.

After months of push-and pull, the German consulate in New York denied our visas to go get our green cards in Frankfurt, for reasons “unknown.” Why would we stay in Germany if we’re finally getting our status in the United States? At the time, we had no idea how far it would push us back. Would it be another nine years?! But, thankfully, it was only another year, and the appointment was in Juarez, Mexico.

A border town, Juarez still has a reputation for danger, danger, danger. No matter, this was happening. We booked a couple of motel rooms, flew down to El Paso, Texas then walked over to Mexico in 1994. I love crossing invisible lines that mean everything to us. I still quietly rejoice when I spot a “Welcome to fill-in-the-blank” sign.

In Juarez, we woke up before dawn and headed over to the consulate each day to dutifully take our place on endless lines that snaked with other anxious immigrants. Families from all over the world stood in that blue light just before sunrise, clutching their documents. Some had briefcases, others had brown accordion folders, the ones with the elastic fastener. Everyone had documents. They are the end-all, be-all for immigrants. They are your everything. They are all you have. They are your past, your present and your future. (While one of the signs of my empowerment as a citizen is to play a little fast and loose with documents, I still have a folder. It’s much smaller now, but it’s still a brown, leather-bound container for my precious documents.)

At night, we would eat out, terrified of diarrhea. You cannot stand in those lines with a churning, already-vulnerable stomach. We had to leave many an appealing salad untouched. After dinner, we craned our necks to watch Jeopardy! on the television suspended from the motel room ceiling. One of the parents from our day-care was on the show. We watched a client win $10,000 at night, and stood among the huddled masses in the day. That was our life as “illegal aliens.”

So how was it that we lived our lives in relative normalcy for all those years? As the undocumented debate today threatens to rip families apart and send people who have only known the United States as home, how was it possible we existed? There was no DACA back then, but if there were, my sister and I would be eligible. Would that mean we would also have to face the reality of moving to Iran? I’m bordering on illiterate in Farsi, fossilized in the first grade.

I spoke with a couple of experts and the answer, in a nutshell, was no. The generally accepted loopholes that allowed our family, as well as countless others, to grow in purgatory while we waited for judgment day closed in 1996. That was the Clinton era.

In an ironic twist, while the conservative Ronald Reagan granted one of the largest swaths of amnesty in recent history in 1986, humanitarian loopholes were closed under the more progressive Bill Clinton. In an even more ironic twist, closing those loopholes forced more people to stay without their papers. The pipeline, especially to Central and South America, was a two-way street before then. Breadwinners would briefly come up to the U.S. to work, then go back home. Now, it was too risky to leave and the U.S. inadvertently encouraged people to bring their families and stay.

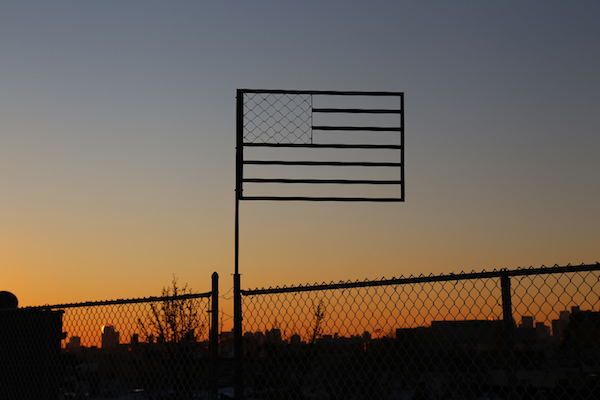

Meet the DREAMERS. Whether virtual or real, these walls often keep people in rather than out. From there, an industry cropped up in the desert to smuggle people across the border, which has led to countless other problems that politicians can point to when demonizing and criminalizing immigrants.

So, was that little girl with the bowl cut who thought hanging around the library was loitering a criminal? Was she damned to illegality no matter how she behaved because of her mere existence?

I don’t know anyone who is undocumented now. In fact, we didn’t really know anyone who was undocumented back then. We lived our lives and we waited. I’m not sure how long that will continue to be a possibility. Stoking fears by pushing travel bans and pulling back DACA will just make people quiet again. They aren’t going back, they just have to hide now, in which case the Trump Administration and its supporters will have the criminals that they seem to be so eager to create.

In the meantime, the ladies who loiter because they aren’t lucky enough to lunch seem to think they have an ally in the White House. But they don’t. Hopefully they realize it before it’s their turn to be criminalized.