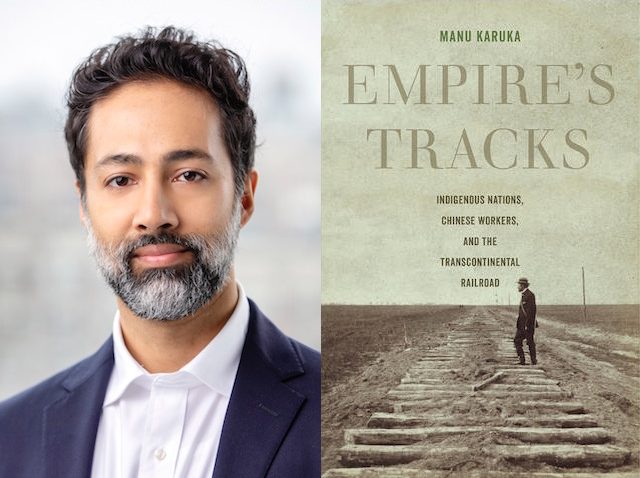

The scholar and author of Empire’s Tracks discusses a history of the American West through Chinese workers, white supremacist violence, and the division of the working class along racial lines.

May 20, 2019

The following is the second half of a two-part interview with Manu Karuka, the author of Empire’s Tracks. Read part one, on anti-imperialist immigrant movements, the alternate history of the Transcontinental Railroad, and the rumor of U.S. sovereignty, here.

Vivek Bald: I want to talk a bit about the strand in Empire’s Tracks that focuses on Chinese railroad workers. You write about Leland Stanford, the industrialist founder of Stanford University who was president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company, and about the Chinese immigrant laborers he relied upon to build the railroad. The connection between the West Coast and notions of whiteness is something that I’ve been thinking about a lot in terms of the riots that drove South Asian immigrant mill workers out of Bellingham, Washington in 1907 and how the Asiatic Exclusion League—the group that stoked the riots—was very explicitly describing the Pacific Northwest as a white man’s territory.

Within the existing work on Asian Exclusion, scholars have marked a shift that occurred when the Chinese went from being “desirable” as cheap labor to being “undesirable” after the railroad was completed. This is a shift that you explore in the book too, but you tie it to settler colonialism and to Indigenous histories. The moment that Chinese migrants become marked as undesirable and needing to be excluded is also the moment in which the territory of the West has been successfully “settled” through years of extreme state and vigilante violence against Indigenous groups, and their dispossession from their lands. And therefore the Chinese who remain—or the Asians who might come in the future—are not undesirable just because they’ve outrun their usefulness as cheap labor, but because they now threaten the dispossession of whites from their newly “settled” territory. To me that that feels like a very important bridge between Asian American and Indigenous histories which also extends our understanding of Chinese Exclusion.

Manu Karuka: Thank you for pulling out those dimensions. Dispossession is part of the fear here—the fear that Chinese people will do to white people on the Pacific Coast what white people have done to Indigenous people on the Pacific Coast. This is something that DuBois wrote about a lot in Black Reconstruction, in The World and Africa, in his later work, that there’s this latent fear among imperialists that the “colored world,” as DuBois put it, would wait no longer and it would exact its price for what had been done to it.

I anchored the book around the category of imperialism, partly because thinking in terms of imperialism and anti-imperialism helps us to see and maybe disrupt the various kinds of exceptionalism that we’ve fallen into. So, of course, there is American exceptionalism and the whole mythology of the frontier and pioneer identities. But I think there’s also an Asian American exceptionalism that’s rooted around the exceptional nature of, say, Exclusion or of what many have understood in terms of the effects of Orientalism within Asian American histories, culture, and politics. I’m interested in disrupting those forms of exceptionalism, and seeing the ways that these relations of power to which Asians in North America were subjected were actually not exceptional, but were shaped in relation to other kinds of relations of power.

In California, I think there’s something that we need to explain: Why was there so much violence directed against Chinese people in the gold fields? What was the nature of this violence, and how was it organized? Exceptionalism serves the narrative that Chinese and other Asian people came to the United States as immigrants and remade themselves as Americans through various processes, including surviving these forms of racist violence.

But if we look at the history of California, then we see that in the years before Chinese people began arriving in large numbers, Indigenous people outnumbered everybody else in the Bay Area. And among recently arrived colonists, organized vigilante groups of men roamed about and just murdered Native people where they found them, hunting them down, systematically destroying their food, systematically destroying their homes and villages, and targeting civilians: children, women, elders, non-combatants. These were not the army or state militias. These were groups of men who organized themselves for this violence. What we now might think of as “whiteness” is something that is historically produced, and in California, in the Bay Area, its production begins in this historical moment of intense, genocidal violence.

So for Chinese people, Indigenous Hawaiians, Chileans, Mexicans, others who then came to the gold fields and engaged in labor, the racist violence they experienced was an outgrowth of that intensely violent process of colonization. Ultimately that violence was about stabilizing property claims to the place, to the land, to the resources on it. For me, colonialism is the framework to understand and explain the nature of the racist violence in this place.

After the railroad was built, there’s a class dimension to the politics of exclusion that I think has been somewhat dormant in our understanding of the politics of Chinese Exclusion. Anti-Asian violence is misdirected ire against massive corporate trusts. Railroad companies were the largest corporations of the time, extremely corrupt. The Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad, these were among the largest corporations in the United States at this time. And they rapidly began to combine into trusts, through which they centralized control over the major rail networks.

White working class organizations began to misdirect their ire and their critique alongside the intensification of their own exploitation, their lower wages, their decreasing quality and standard of living, which they experienced in their daily lives: increasing mortality on the job because of new forms of technology, and the speed in which they’re being forced to work. Rather than organizing their anger against the corporations that were intensifying their exploitation, they organized it and articulated it against Chinese immigration. So Chinese Exclusion became an escape valve for a misdirected anti-corporate critique.

On the other hand, Chinese American merchants misdirected their critique of the Exclusion movement by naming these white nativists as a lawless mob, rather than directing their ire against the United States federal government, which was administering racist border policy, or against the corporations that were working with the federal government to administer and profit from the border policy. So, there was a class dimension, an anti-corporate dimension, and a colonial dimension, and the politics of exclusion redirected and misdirected these critiques, these organized forms of collective anger.

One place where we can see this is Rock Springs, Wyoming, the site of a Union Pacific coal mine. Immigrant workers of different European nationalities were working at this coal mine alongside white people who were born in the U.S., and when those workers went on strike, the company brought in Chinese workers to break the strike. Chinese workers stayed at the mines after the strike, but the the union excluded them from membership. The union would call strikes and the Chinese workers, because they weren’t allowed to join the union, went to work. They wouldn’t respect the strike. This went on for several years until September of 1885, when it exploded in a massacre of Chinese workers. People were chasing them in the hills surrounding Rock Springs and gunning them down. The police were watching and didn’t do anything.

We can see the massacre as a flare up of white supremacy, of a a white claim on the land. But I’m more compelled in seeing it as a moment of failure of working class solidarity. The massacre was a failure of working class organization, and it was a defeat for the working class in Rock Springs. The union learned lessons from this defeat. A generation afterwards, Rock Springs had one of the first interracial mine unions in the region, organizing Chinese and Japanese workers into the union. In the most painful way, the workers learned a lesson. The lesson, for me, is not primarily about white territorialization, so much as the division of the working class along racial lines, and through that division, the fracturing of solidarity, and the cementing of corporate power.