“It’s not really about trauma—it’s about what it means to resurrect out of that.”

December 7, 2021

This fall, Mai Der Vang and Sophia Terazawa both released poetry collections that reckon with history and the ways governments cover up and warp that history. In Yellow Rain (Graywolf Press), Vang investigates an episode from the 1970s in Laos that remains contested and often forgotten, in which Hmong people experienced “yellow rain,” a mysterious substance that fell from planes, after the United States abandoned the Hmong at the end of the Secret War. Thousands of Hmong died, while the U.S. government sought to blame the Soviet Union–backed Laotian government and later discredit and deny Hmong testimony. Playing with collage, media reports, scholarly works, declassified documents and cables from the U.S. government, and Hmong testimony about yellow rain, Vang rebuts the versions of events provided by the U.S. state and media, and centers the Hmong experience. In Winter Phoenix (Deep Vellum), which takes the form of an abecedarian, Terazawa addresses the legacy of the Resistance War Against America in Vietnam, but also shows the speaker, a daughter of a Vietnamese refugee, seeking to stop cycles of violence and generational silence. Like Vang, Terazawa draws on other texts—in her case, testimonies given by U.S. military personnel during war crime tribunals in the 60s and 70s—to conjure a polyvocal, formally inventive collection that unearths the crimes of an empire.

While both Yellow Rain and Winter Phoenix deal with painful and violent histories, both collections are, as Terazawa says, not really about war or trauma. “It’s about what it means to resurrect out of that,” she says. Vang says, “We tap into something that is trying to create a space to be heard again whether it’s our ancestors or some energy that demands justice for what’s happened. Those are the shadows that stay with us until . . . we go and cut off the head of the thing and purge it of all that it is.”

The poets each contributed an audio recording of a poem, and in late September, talked with one another over Zoom about their work.

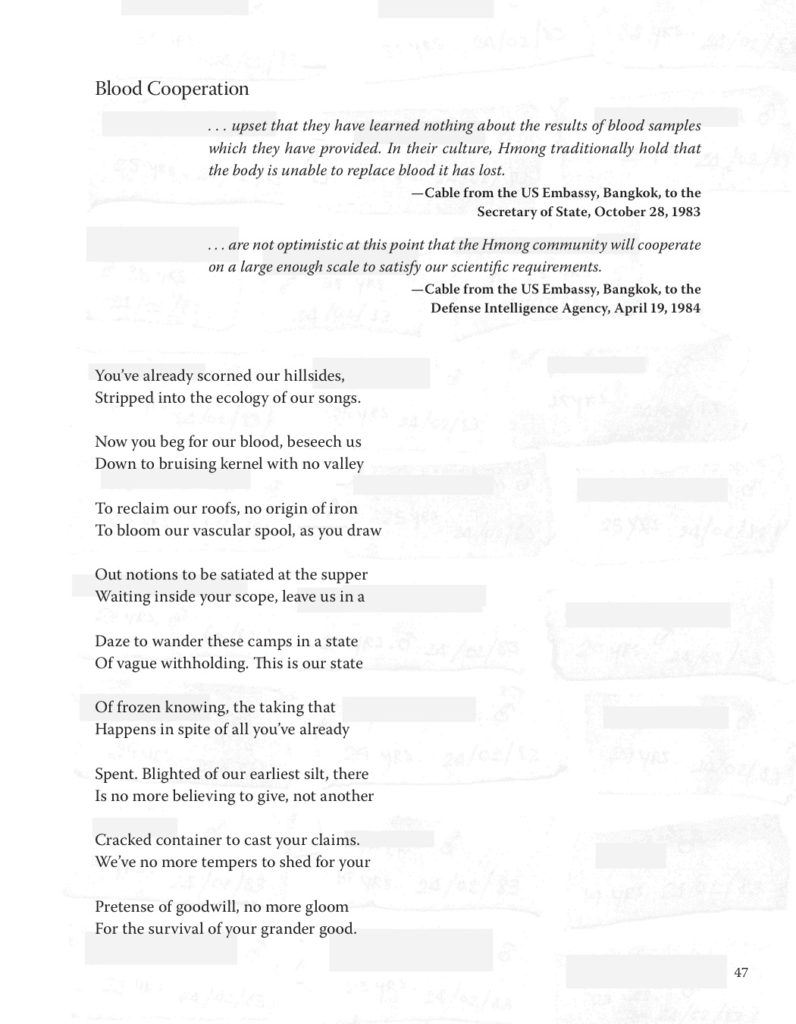

Mai Der Vang’s “Blood Cooperation”

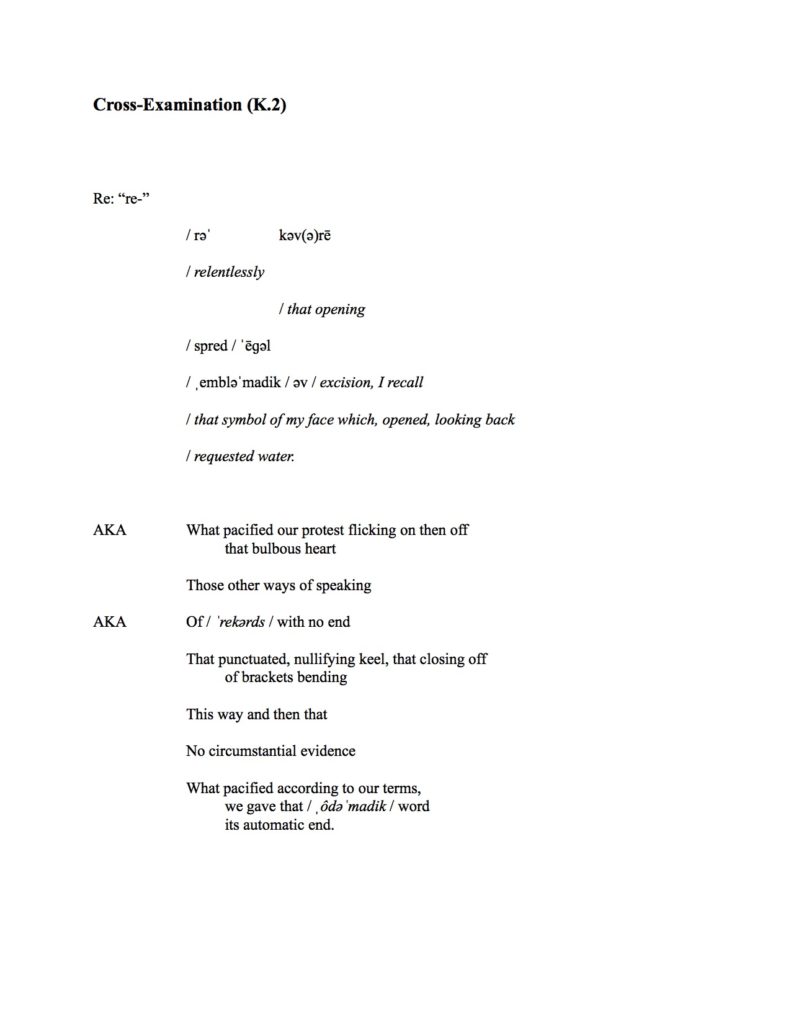

Sophia Terazawa’s “Cross-Examination (K.2)”

Sophia Terazawa

Both your books, Afterland and Yellow Rain, deal with a kind of history that has been made dormant by both the state but also by collective memory. It’s something I think about in my craft as well: When do we wake up history? And how do we wake up history?

Mai Der Vang

I love this question because that’s what I was trying to do with this second book: reopen that history, resurrect that history, re-reckon with that history. I came to a point where I was like, “I’m ready to write this book.” This book has been a long time coming.

I grew up in a Hmong family. As refugees from Laos, my parents resettled here in the early 80s. Growing up as a kid in a refugee family, we didn’t have access to literature in the ways that we have now. So I wasn’t in a position where I was ready to reckon with any of this. Only now have decades passed and the children have grown up. And in that passage of time, I’ve been able to experience and internalize the impact of that history—that is still happening—and that trauma on my parents, the elders, and ancestors, to now be ready to try and write about it. It’s taken this long for us to grow up, and maybe that’s why we’re now seeing this huge, tremendous, inspiring wave of literature coming out from children of refugees.

That I think speaks in some ways to your work. Which I want to turn to now, because I’m so happy to have a copy. [Holds up Winter Phoenix.] It’s a gift to behold this book in my hands.

Tell me about your experience. I’m particularly interested in the way you used the work, the testimonies, the documentation to serve as something that might be a restorative or healing component of the poetry.

ST

I think about the word you used previously: resurrection. I think there’s a lot of synergy between your work and my work. You also began your book with a statement on being the daughter of refugees, and in my book I also mention that this book is not really about war. It’s not really about trauma—it’s about what it means to resurrect out of that.

And for me, the seed for this book was honestly heartbreak. I had my heart broken pretty badly in 2017 and was very lost, and [searching for] a language to look at that heartbreak and where it came from. I keep going back to a statement James Baldwin once made in an interview, saying that you can always think your heartbreak is the worst in the world but then you just read a novel and you realize that it’s not—it’s the heartbreak of humanity.

Once I started to think about my own heartbreak as part of a larger state of humanity, I realized that the way I feel and operate in this world is out of what I’ve inherited from my mom. Like my mom being heartbroken by her country. Or being heartbroken by her family or her people. Essentially that’s what a refugee is—it’s the ultimate form of rejection, right? You’re rejected by the land that you’re from; you’re rejected by your own history. So I was able to enter the book in that way.

I want to pivot to a conversation about channeling and shamanism, because that’s what helped me stay sane writing this book. Because we’re playing with forces that should—at least to a lot of people—stay in the ground, should stay dead. You mentioned in your book that a lot of times the government documents basically imply these bodies should stay quiet, should stay hidden. What we’re doing is resurrecting these moments. Thankfully I had a really great cohort at my MFA, a really great mentoring system, and some really great people around me who loved and cared for me and allowed me to have that space to resurrect.

Was that a similar experience for you? Did it feel like you were entering a territory that you might have felt a little bit small in, but that you felt had something you needed in terms of magic or channeling? Did you feel like you were strong enough to channel that history?

MDV

Sometimes as a poet I don’t know that I’m ever strong enough. And if I feel not strong enough to confront or come up against the thing I’m writing about, then I know it’s what I should be writing about. If I come to something and I’m able to get at it without much effort, then perhaps I’m not pushing far enough just yet. Perhaps there’s another level in my thinking, or another branch in the conversation, that I’ve yet to breach.

I felt exactly like you’re saying—small against the work, uncertain about where it’s taking me, terrified by the ghost of the speakers in the poems—a lot with this collection. I felt it with my first collection, too, in writing poems I never thought I would write. I didn’t know that I wanted to enter those spaces. And when I accepted it and said, “This is where I’m going,” I allowed myself to inherit a new form of agency where I could confront the shadows of the work.

Beyond the labor of the page, there’s the labor of confronting the shadows. Sometimes I have to remind myself to care for myself. I have to step away sometimes. I have to come out of the work for a moment so I can ground myself back in my reality, in my present moment. The work humbles me all the time. There’s still so much I don’t know about what I’m doing in this work and that’s okay. I don’t have to have all the answers. There isn’t one right way to do this work. If I have any feelings of uncertainty at all, then I’m on the right path.

But thank you so much for asking that. I love that question. What about you?

ST

In writing Winter Phoenix, I wanted to lead with justice. I wanted to lead with not just history but restorative history. And I just wasn’t sure if the method I was pursuing—using the form of testimonies—was the best form. But it served as the most tangible form that I could work with. I was thinking about the modes of justice that had been pursued after the U.S. War in Vietnam. And really all I could find were these testimonies from the Winter Soldier Investigation, from the Russell Tribunal Investigations. I wanted to use that template as a vessel to fill in the language. But the book just started overflowing. It makes me think of the movie Princess Mononoke. Have you seen the movie?

MDV

I have not, no.

ST

It’s one of the best movies ever, you should definitely see it! There’s this spirit/god of the forest who gets its head cut off at one point, and in search of its head, the spirit starts to overflow and take over the land and destroy all the beings in its path. That’s how it kind of feels—like I’ve cut off the head of something and suddenly it’s overflowing.

So the biggest challenge for me in writing this book was knowing how to stop. I’m glad that writing poetry forced me to pick and choose which words do come out. For me it was a lot of channeling. It was like I was asking these spirits or this history to talk to me, but I was getting five thousand voices at once and trying to figure out which voice to put on the page, which one to respectfully push away, which one to delete.

MDV

I love this. Sophia, this is amazing.

I wholeheartedly agree—anyone who writes channels something or someone or some aspect outside of who they are. Sometimes that’s when you look at a poem and you’re like, “I don’t know who wrote this. This is not what I would normally do.” I was raised in a family that practiced and continues to practice shamanism where much of that healing comes from being able to step outside of yourself and connect with something beyond you. I feel we do that as poets. We tap into something that is trying to create a space to be heard again whether it’s our ancestors or some energy that demands justice for what’s happened. Those are the shadows that stay with us until, like you said, we go and cut off the head of the thing and purge it of all that it is. Before it finally can be put to rest.

Could you talk about crafting the language for Winter Phoenix? Thinking about the construction of the language around these testimonies and the poems and even the exhibits and affirmations—I’m curious what kind of channeling was happening for you.

ST

I’m not very methodical when it comes to the way the words take shape on my page. I guess it’s a kind of lyric. I’m very sensitive to sound and rhythm, so it is an internal lyric that I’m carrying with me—I don’t know if it’s ancestral or just my inner voice that comes out.

In terms of how it gets shaped into the exhibits and into the form itself—there wasn’t really any method to it. I don’t know how to explain it. I knew these words were coming out really quickly, so I was like a bouncer to the words. I was like, “You’ve got to stand in line, you guys.” I remember saying, “All the A’s come to the front.” And so we did the A’s. I remember just channeling anything that was related to the sound “ah,” and that’s where the abecedarian form came out. And then the B’s came. And in terms of breaking that up into exhibits—it was simply that I would have a testimony and I would still feel things coming, and then I would feel, “Well, there needs to be an image. Or there needs to be proof.” So in my mind I thought, “Oh well, an exhibit.” So I would have the overflow, so to speak, come in and fill that out. And then later on, I started adding visual diagrams. I wanted to incorporate things I was seeing come in. Ultimately, in the closing statement—that was the last poem I wrote for this book, this entire book was pretty much written in chronological order—I was like, “Ok, now everybody come on in.” I wanted to synthesize everything all at once in that final long poem.

I remember in writing that last poem, I had an image of bees. Bees weren’t in my book until the very end, but I just remembered I wrote down a quote from your book, “I break the pages and let the bees fly out.” Was that your method around this book as well? Did you have to break the page and all these bees just came swarming out?

MDV

The idea of cutting the head of something and things just splurging out is equivalent to the bees for me. Allowing the bees to go free.

I love your closing piece because of the way you’re describing it, but also because of your astute and diligent consideration for syntax. And the construction of the clauses. It’s even more profound to hear you talk about how you channeled much of that language.

There is that one phrase that repeats throughout the entire collection and feels very incantatory and leaves a haunting quality throughout the pages, the phrase: “Why did you just stand there and say nothing?” I wondered if you could talk a little bit about that if you’re feeling up to it. To talk about your thinking on the power of that repetition.

ST

Thank you so much for asking that question. I appreciate that we are entering this conversation with so much care. I will say that it is directly addressed to my biological mother. At the core of this book, there is also a trauma I’ve been working on in my own history of sexual assault and sexual violence. And the biggest trauma around that has been watching my mom react to that trauma in me and then realizing to some extent that—and this is not a conversation that we’ve really addressed as mother and daughter—this is possibly a kind of lineage I am reliving. So we were basically retraumatizing each other through this history.

“Why did you just stand there and say nothing?” is a phrase I’ve carried with me since I was little. I don’t think it was necessarily directed toward my mother, but it was a voice I could hear my mother saying to her mother, and possibly her mother saying to her mother. So it’s like this cycle of us looking at our caretaker and saying, “Why did you just stand there and say nothing?” But the sad irony is that we’ve had to ask that of somebody else before us. I don’t know if it’s resurrecting anything, but in terms of how it might heal us—by me asking that statement, I want it to stop with me. And whoever comes after me, whether it’s biological or not, I don’t want them to ever ask that question. Or ever need to ask that question. The act of uttering it over and over again kind of allows it to take a physical shape so that it doesn’t get passed down psychically.

MDV

That makes complete sense. The act of being able to utter it again and again is the speaker saying, “This is the last time you’re going to have to show your face.” Or, “This is it. No more after this.” I felt there was a kind of assertion coming through from the speaker in the willingness to say that again and again, and I just want to applaud you for the courage, the literary courage, of doing that in this work.

ST

That’s so kind of you—thank you.

With my work, I look at documents from the 60s or the 70s, whereas your work overlaps generationally a bit more closely to your own. For you, a lot of the people who wrote those documents or who are complicit or who were directly affected by yellow rain are still around and alive. How do you feel about uttering words spoken by people who are still with us? Is there something different there for you?

MDV

Confronting that question is still a block in the larger historical understanding of what’s happened. There are some people who are no longer around as far as the political figureheads go. To my knowledge, yellow rain is not really discussed within the Hmong community. When we think of Hmong, we think a lot about the Secret War, but we don’t think enough about the erasure and dismissal of the yellow rain allegations, and perhaps we should. It’s a history shrouded in mystery and a huge lack of remembrance towards and potential understanding about. There are Hmong Americans in the generation after me who have never even heard of yellow rain, that don’t even know this is part of what has happened to the elders, this is a fallout of the war.

It feels like I’m constantly clawing at something to try and get it out, but forces are continuing to put dirt on top of it. I’ve learned that I have to be relentless in this work. Like when you were saying that your book kept getting bigger and bigger, and you kept writing and writing but more just kept coming and coming. I felt the same with Yellow Rain; there were so many moving parts to what happened. Even for me, I was learning about it, trying to wrap my head around the whole fiasco of it, the political implications of who was taking what side and what angles and agendas were being applied over the whole story of yellow rain. And how within the middle of that political fiasco, the Hmong were the collateral fallout of this larger discourse happening between these two sides of the government. That’s the feeling that stays with me—that as a writer of color, as a daughter of refugees, as a Hmong person, I’m constantly having to shovel my way through this work again and again. And for my own community, there are still so many people who have yet to learn what’s happened.

There was actually more to this collection, but it was getting too massive. I had to stop.

ST

You had overflow as well?

MDV

I did. I had to cut out a lot of stuff and probably for the better. As a poet, I try to be diligent about space in some way, shape, or form. For me it was: How much am I going to tell? What needs to be told? What aspects of that thing need to come out? Sometimes, the heartbreaking reality is that we won’t be able to tell everything. There’s always something that will get left out of that larger narrative.

ST

I saw several different images while you were speaking. First I had an image of you at a table shuffling papers around, all these documents, especially governmental documents, which I know you put in your book especially toward the end. It also made me think of papier-mâché—it’s like you’re glueing these documents on top of each other, and of course some negate others, but ultimately it creates this hardened shell. And it comes back in my mind to the beehive, because that’s how beehives form—little shells put on top of each other until it becomes this hard mass. And I think about that too with your book.

I think what’s really exciting in your book was that it felt like the kind of book where if poems were taken out in one way, they could be put in another part of the book and it would completely shift the book in a really powerful way. How do you imagine an audience receiving this book in possibly alternative ways? I’m imagining on a larger political scale—I do think about other groups of people who have been disenfranchised, or have experienced traumas by the state in various ways. Do you imagine them being able to see this book and how it channels into their own histories and stories?

MDV

I hope that any person of any community who has experienced displacement, genocide, war, disenfranchisement—crimes of empire—will find a thread or bridge of solidarity in this work. And to have moments where we see that whether the crimes that have been committed against us are the same or different, there is that shared hope toward liberation of each other, of ourselves.

It’s interesting, the question you’re asking also has a lot to do with the way the poems are structured and ordered. The original question you asked: If they moved around, what new narratives would come out of them? You had that image of me shuffling papers—yes, that happened. I had to have a lot of tablespace to work with all the declassified documents. I ended up printing out a lot of things because I wanted to experience the documents in their most crude form, as a piece of paper that was passed around. It was a challenge to decide how to broach the ordering because I’m aware that not a lot of people know about yellow rain. So there was the burden of having to tell that in a particular way so my reader could engage with the history. And if I told it in a different way, it made me wonder if my reader was going to be able to understand—how do I construct this complex narrative in a way that allows my reader to walk alongside with me? To understand what’s at stake.

What was at stake, at least for me, was the erasure of the trauma and how to depict that. I did play around with moving things in and out; there was still so much that I didn’t get in there. But I think what’s there now offers to the best of my ability a counternarrative on yellow rain, along with a chance for readers to make their own discoveries as to other histories that might have been buried by the state, by the government, by empires, to then be able to do their work of unburying alongside me. And I hope that anyone who can relate to that, any community who has experienced that kind of grief, can share in that solidarity with me.

The work that we’re doing is work—we’re not only laboring with language and the page, but we’re laboring with the shadows that look over this work, the shadows of the histories that have happened and are continuing to happen. So what do you do for self-care, to be able to come back to this work?

ST

I was in a very dissociated state when I worked on this book. I remember having days at a time where I would just pour into this work. And then I’d step away from it. It only took maybe a year and a half to write all this book, and the editing was very minimal. I don’t really edit my work too much except maybe for when I’m transferring from paper to computer; I might change some spacing or a word here or there. It kind of feels—not sacred, but it feels like I can’t touch the work after it’s out. It’s been given to me and my job is simply to be the messenger and make sure that it’s given its proper shape legibly. I haven’t really allowed myself to come back to this work; it strictly feels like a document at this point. It’s in the archive now. It’s part of my past, and it’s like a sibling and it’s like I’m letting them do their thing. And so that does help in terms of self-care. In terms of whether or not I will return to this voice or return to this mode of being—I don’t know if I’m open to it just yet. Mentally, once I finished the book’s closing statement I’d closed that door. It was like done and I locked it. Maybe that’s part of my self-care process.

MDV

Absolutely, for sure. We definitely need to let the work live on its own, right? Because once it’s a book like this, it’s its own thing. It’s its own being, it’s an entity of itself. That’s the part of writing that can be so transformative. The book has been born.

ST

And ironically, I’m not attached to it much. How do you feel at the end of writing your book? Do you feel like you’re able to let it go, or is there any kind of attachment, good or bad?

MDV

I have moments where I come back to poems like, “Ah, I should have done this differently, or I could have done that differently.” But at some point, you just gotta stop. You gotta let it go, and let it be its thing. I’m not eager to come back and spend more time on these poems. I invested many years in Yellow Rain, and now it’s time for the thing to be its own thing. As much as it is still a part of who I am, it now has its own agency, it has a cover, it has a binding, it has pages, it has a body. That’s the least I can do for it—give it that body.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.