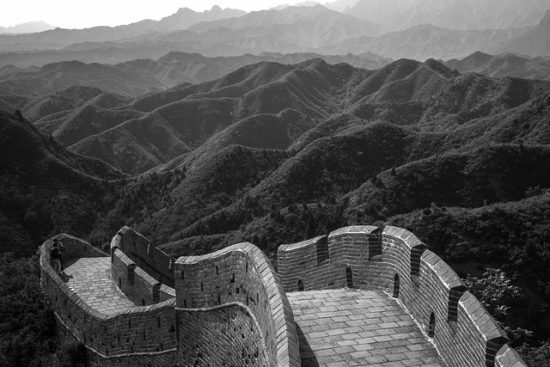

Why Donald Trump is so wrong about comparing his planned U.S. border wall with the Great Wall of China.

February 21, 2017

Every time Donald Trump brings up his plan to build a wall along the U.S. southern border, all of China should thank him. His obsession to build the wall on the U.S.-Mexico border has drawn attention to one of the most, if not the most, famous walls in world history—the Great Wall of China.

And this is a boon to China’s tourism industry.

Comparing the Great Wall to Trump’s southern border wall is not the media’s invention but Trump’s own. As early as August 2015, he told Fox News host Bill O’Reilly, who was questioning the feasibility of building a wall: “You know the Great Wall of China? Built a long time ago, it is 13,000 miles. I mean, you’re talking about big stuff. We’re talking about peanuts, by comparison, to that,” Trump said at that time.

The analogy is probably one of the best that Trump has made since he came into the political realm. Unlike the unfounded correlations he wanted us to believe between Mexicans and rapists, between immigrants and criminals, and between journalists and liars, the Great Wall of China and Trump’s border wall do have many similarities.

They both are long: The Great Wall, 13,000 miles long according to the official count of China, is designated as the eighth wonder in the world in many folklores; and the Trump wall, 1,250 miles as planned, will not be a world wonder but will be the longest wall in the U.S. for sure.

They are both costly: Most dynasties in ancient China built or renovated the Great Wall. And the Great Wall we see today was built mostly during the time of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), at a cost of 2,425 tons of silver, about the entire revenue of the country for 10 years at that time. And Trump’s wall, according to a newly leaked report from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is going to cost about $21.6 billion, well over Trump’s previous estimate of $12 billion.

Like the Great Wall, the Mexico Wall—which Trump claims will keep “bad hombres” out of the U.S.—will be a burden to the average American. In China, even children know a folktale about an ill-fated newly wed couple. In this Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.) story, the woman called Meng Jiang jumped into the ocean when she found out her husband died at the construction site.

Her husband, like many other men, was forced by the Emperor to build the wall. He was among the close to one million people who died building it.

Trump’s wall won’t likely use forced labor. But there will be casualties on a project like this. And taxpayers will definitely bear the brunt of paying for the wall, unless Mexico suddenly reverses course and picks up the tab, just like what Trump has been harping all these times.

The similarities go beyond the bricks and mortar. For example, the Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who founded the Qin Dynasty, did not only connect the various border walls to make them into the Great Wall for the first time; but he also buried hundreds of intellectuals alive to shut them up. Journalists in the U.S. are not in danger of being buried alive, but the Trump administration has already barked at the media to shut up.

Even some lyrics from “The Great Wall,” a 2004 song by the since-disbanded Hong Kong rock band Beyond, seem to eerily fit the Trump wall, too. It talks about a broken-down, decrepit wall that “encloses an aging country” where there are “superstitious villages” and the “Emperor has new clothes.”

But what may be the most noteworthy resemblance between the two walls is that the Great Wall didn’t really serve its original mission and Trump’s wall is destined to fail its mission too.

The Great Wall was initially built to protect China from the invasion of the northern nomads. Still, despite the Great Wall, China was overrun by none other than the very northern nomads that it wanted to fence out. The Ming Dynasty, during which the Great Wall spanned over 15 provinces stretching from Liaoning in the east to Gansu in the west, was overthrown by the Manchus who broke through the Great Wall in the summer of 1644 and ruled China for the next 268 years.

In modern times, despite efforts by the communist government to reaffirm the Great Wall as a symbol of the country’s might, some dissident artists reinterpret it in their own ways. One of them, my friend Zheng Lianjie, ran to the Great Wall in the mountains in September 1990 when news of the fall of the Berlin Wall almost a year earlier finally seeped through Beijing’s wall of censorship and reached him.

In the three years after that, Zheng has been doing a series of performance artworks themed on the Great Wall, winning him worldwide recognition. In one of them, he wrapped tens of thousands of abandoned bricks in red cloth and laid them on top of the Great Wall. To him, the Great Wall is not a torch of pride but a bleeding scar on Earth.

Zheng and many other dissident Chinese artists like him are now living in the U.S. They came here because they believe there’s more freedom here and that the culture here is more inclusive. They never thought that in 2017, Trump’s U.S.A. will adopt an idea from thousands of years ago, and will try to stop the influx of people with a concrete wall.

One thing that all walls share in common is that from the day they are erected, they are destined to collapse — sooner or later. The Berlin Wall is gone. And Hadrian’s Wall, which separated the Roman Empire from the northern “barbarians” in Britain, was abandoned and much of it has disappeared.

The Great Wall, though it still stands today, thanks to the Chinese government’s pouring in heavy investment for its renovation, has lost its use as a divider between “we” and “they”. It is great today because it is a magnet for tourists from around the world, a purpose that its original builders had never dreamed of.

But what’s really disheartening is the fact that the harm that a wall inflicts often outlives the wall itself.

Take the Chinese Exclusion Act, a legislative wall that rose in 1882 to stop the Chinese from emigrating to the U.S. The discriminatory law was repealed in 1943, but from then until 1965, U.S. immigration law allowed only a maximum quota of 105 Chinese migrants to enter the U.S. every year.

It was only in 2012 that the U.S. Congress apologized for its discriminatory policy against the Chinese, 130 years after the Chinese Exclusion Act took effect.

At a 2009 exhibition called “Over the Wall,” held by a New York gallery for the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, I met Yuri Solomko, a Ukrainian artist who is known for implanting maps in all his paintings. He told me it was the collapse of the Berlin Wall that gave him the idea. He said when a wall falls, people always draw new boundaries between one another.

In other words, the building of one physical wall could easily help erect hundreds and thousands of walls in people’s minds. And demolishing these invisible walls takes much, much longer than destroying the physical ones.