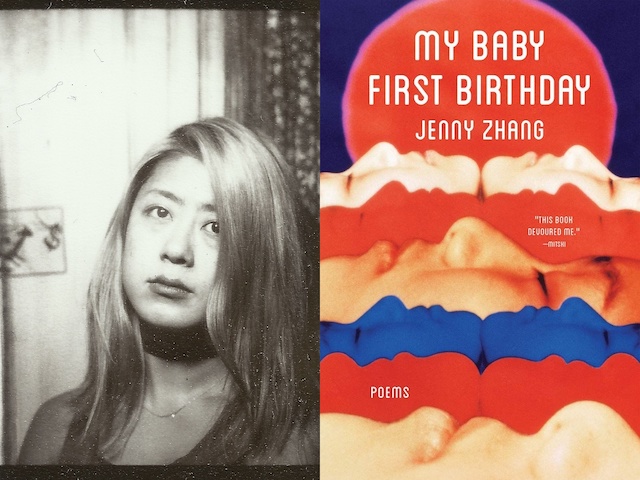

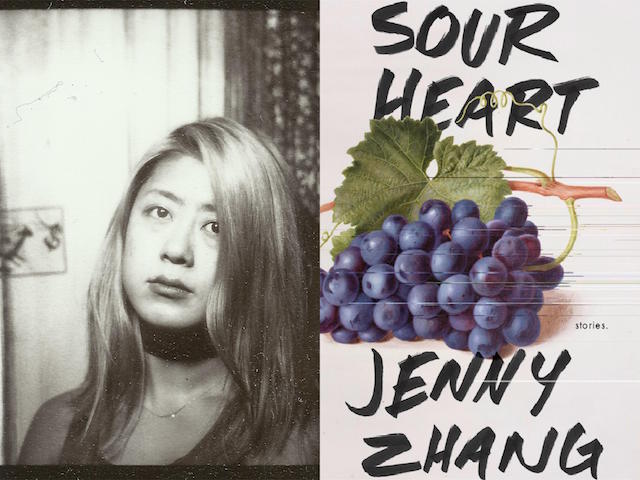

The author of Sour Heart talks about channeling childhood in her fiction, balancing the soft with the scratchy in her stories, and getting tokenized as an Asian American writer.

September 7, 2017

One does not forget the first time they experience the work of Jenny Zhang. For me, it was a visual diary of Zhang’s time in Vilnius, Lithuania—a place from which I had just returned. In the piece, Zhang describes the act of bracing herself against lampposts and buildings in bouts of incessant crying; she observes the wonder of a new place, a “sourness” supplanted by narrative and “blue heroines.” I was hooked.

Zhang’s voice has proven itself a consistent and singular medium for the binding and sundering it begs of us. Achingly tender yet scratchy on the throat; her work is defamiliarizing in its language and, somehow, still, effortlessly close. In Sour Heart, Zhang’s debut story collection, one feels as if they are engaged in a long conversation with its young narrators. They do their best to cross their most monstrous desires, to dilate their most earnest susceptibilities—they plead; they scream; they curl up with you to tell you where they’ve been and how it is.

I spoke to Jenny on the phone on a Wednesday afternoon. I felt shaky, a bit terrified (I am shy and this is Jenny Zhang) but Zhang was so full of warmth, so incredibly disarming and sharp. I remembered how good it felt, how good it still feels, to be cradled by the words of an artist with such concentrated sensitivity to the world—to bear witness.

—T Kira Madden

T Kira Madden: In preparation for this piece, I read Sour Heart twice and caught up on all the interviews you’ve been doing since the launch. It was a little daunting! You’re in this terrific position where you have a great deal of media surrounding the book, so many thoughtful pieces and conversations. I wondered how I might come up with questions that feel new to you—so many had already been answered—so many of the same topics have already been pressed. As the author on the other side of that, I wonder if you feel your answers have been changing, or shifting, through observation and repetition with the same inquiries. What are you tired of hearing? What have you only just begun answering?

Jenny Zhang: I’m learning a lot about the media. Sometimes it becomes really clear that a publication wants me to fulfill some kind of role where I’m used as a proxy in their attempt to show that they’re interested in diverse voices and that they haven’t erased the Asian American experience. I’m being asked about how I think immigration has changed in the last 20 years—I don’t know; I’m not a sociologist or a historian or political scientist. I’m not an academic scholar of how immigration has changed in the last 20 years, and I don’t even see how the very fact of me having written stories that are narrated by the children of immigrants qualifies me to say anything about immigration except how it functions in the literature that I’ve written in the fictional world I’ve created. And then there are times when a person treats me like a literary writer rather than an anthropologist, or a pundit, or an expert, and those are great interviews because I get to talk from the place of a literary writer, which I am. I’m not the authority on literature, but I’ve certainly spent more time studying and thinking about literature and literary fiction than I have about the sociological ebbs and flows of immigration in America.

But you’re an Asian American writer writing Asian American characters. You must be the voice!

It’s very odd to be made so symbolic by these publications that are looking for me to speak more symbolically, looking for me to be representative of an entire group of people. It’s interesting to see what people focus on and what questions are repeated and also which questions are never asked, and it’s caused me to almost misremember what I wrote. It’s like when you go on vacation and you take a bunch of photos and you forget everything that happened outside of those photos. Your memories become the photos and the stories around those photos. I’m beginning to forget other aspects of my stories because I’m asked the same questions: Why did you choose to write about girlhood? And why did you choose to write about this particular group of families? Why are the families loosely interconnected? Why is there so much gross material? Those questions get asked so much I forget the other elements; it’s had a warping effect.

In Sour Heart, I loved reading these incredibly complex and beautifully crafted run-on sentences. The stories themselves are also fairly long, a refreshing shift from what I’ve been noticing in contemporary fiction, and also a bit different—stylistically and sonically—than your other work. What effect do you think this exhaustive long-windedness has on the book? The cadence feels so specific, so deliberate.

I was really channeling childhood in all these stories, particularly the feeling of being a kid and being paid attention—sometimes for the wrong reasons—and also not being paid attention when you are crying out for it. It felt right for this cohort of narrators, that they would have this voice that was at once insistent and repetitive and breathless. They have these big oversized huge appetites and big oversized desires. There’s a reason kids can be annoying sometimes—they say the same things over and over again, they never get tired, they only stop when they fall asleep. When kids are not self-conscious and not told to shut up or be quiet, they can really go on, and insist, and it felt right to channel that in the language. Also, I’m really interested in maximalism and less interested in minimalism. I wasn’t interested in spare prose. Maybe that was a reaction to the MFA workshop mode of writing—the clean lines are what’s praised.

The MFA Carver stories?

Yes. Every workshop you hear, “I love the economy of language!” and I’m like, “Why?” Why save and scrimp on language? It never made any sense to me. I want to be wasteful with language. I don’t want to save up. I do love spare prose, but there can be a misogynistic attitude about it. An attitude that says women should be prim and neat and not spill over and please take up as little space as possible and walk around with your shirt tucked in nicely and your slip can’t be showing; I don’t care about that.

And your work does not care about that.

I want these stories to be loose with undergarments showing.

Your stories have such a closeness in voice in their indirect discourse, and, when I’m thinking about them, I almost forget sometimes that they aren’t written in the present tense. I love your choice of using a retrospective point of view; it made me think so much about the vantage point from which this narrator is thinking back or recalling the story. Why did you choose to use this point of telling rather than write the story in the present action of girlhood? What freedom did this give you as a writer?

I wanted there to be a lot of space between the events recounted and where the narrator is now. I wanted to play with the idea of how easy it is for us to slip back into a time in the past and how there’s a performance involved in doing that, in convincing ourselves that we know exactly what happened to us 20 years ago. Also, many of the stories begin one way—perhaps very confident, or defensive, or nostalgically idealizing their childhood, or the opposite: romanticizing the hardships of their childhoods—then, as the story progresses, I chip away at that set up. I want to show that the story that they’ve been telling themselves about their childhoods are beginning to break down; I want my narrators to run into contradictions. The voice often changes by the end, and I don’t think there would have been room to do that if the stories were stuck in the prison of the present tense, with things unfolding page by page, moment by moment.

I absolutely felt that in the work. As you were talking I was thinking about your story “The Empty The Empty The Empty.”

Yes!

That voice that begins the piece—there’s a pomposity to it, an arrogance. By the end—well, I don’t even have the words—I’m destroyed right along with the narrator. That persona completely dissolves. And there’s that beautiful moment—the last line—where your character is quite literally looking down at herself.

Thank you. That was my great hope.

I know you’ve already been asked about your use of the grotesque and tender in your work. My question is not about how you do it, or why—it’s clearly just one of your gifts—but I am curious about how conscious you are of that dichotomy, particularly in revision. Do you ever feel, or are you ever told, that you have to fine-tune that balance? The comedy and tragedy, the brutality and tenderness, the violence and sexuality? I’m editing my own book right now and I’ve been told, “you need breathers; give your readers a breather!” Do you ever feel like you need to add moments of reprieve, or sweetness? Do you ever feel like you have to negotiate with your audience?

Definitely. My editor Kaela Myers is really, really intuitive about that, too. Each of these stories were initially written individually without the knowledge that they would all be interlinked, or part of one book, and when they came together I had to consider what kind of texture I was creating. Each story might have its own texture, but the seven stories together create something else. The order in which stories are presented creates, well, a feeling. And texture is the word I’m using deliberately because sometimes it’s that simple: Ok, I need to be soft now; it’s been so scratchy and hard for 70 pages.

In revision, I considered the internal needs of each story, but I also considered the interpersonal needs of each story. I tried not to think about how they would be received, but it’s hard to forget the original feedback, in school, and amongst my peers. Sometimes half the class would say keep doing this, go hard, and the other half would tell me to stop. That stayed with me when revising, and it made me wonder: how many people will I turn off with this? And how many people will I enchant and pull in? One can’t guess accurately but I did wonder if it would cross a line for some people, if they would put the book down. I hope readers will have faith and some charity in following me and believing that I’m not leading them to a dank, dark pool of horror.

I like your pools of horror best.

Thank you!

What is your favorite moment of a story when you’re writing it, and what’s your favorite moment of a story as a reader?

I like the moment—even though it’s a really difficult moment—but it comes just after I feel like I can’t finish a story. The moment when I’m not sure if I wrote a story that I want to see through to the end, or if it’s worth it, or if my idea was juvenile or not advanced or not worth continuing. And then: that feeling when suddenly I know exactly what’s supposed to happen next, the moment when I know I can get to the finish line, I can run a little more, yes, I know where I’m going. I love that energy because it comes out of feeling pretty dejected, pretty low about myself as a writer.

As a reader—I’m a sucker for endings. I’m a sucker for the moment right before an ending. I’m very susceptible to looking at the pages—that physical feeling—there’s only this many to go, I’m getting to the end. And then I’m prepared to feel something intensely. I’m prepared for release; I’m prepared for an emotional high. I love to see how writers end things because it’s so hard—to end something.

For what it’s worth, I asked that question because I admire your endings so much. As I was reading I thought: this is a person who loves endings, who honors that moment of transcendence before the final breath.

I want beauty. I want everything to end with an image of beauty, even if it fades away into the air. Maybe that makes me sentimental.

We started this phone conversation talking about the state of the world. I’ve found it difficult to get out of bed most days, never mind producing and editing new work. I guess my question for you, a writer who’s been so prolific and politically vocal, is: How does an artist persist? How does an artist continue making, and creating, and feeling, when we are currently living under an administration that tells us art doesn’t matter? That certain voices, and lives, don’t matter?

For anyone else with a love and hope for humanity, it’s really demoralizing. It’s really scary to feel like the world is crumbling at a fast rate, and that individuals have very little power to change things, especially when we are worrying about things like a nuclear war. What can we actually do? After the election I had this feeling that maybe other people have had, too; I felt embarrassed and ashamed to tell people that I wrote a book, to begin promoting a book of short stories. I felt that there was so little space, so little heart in the world. Why would I ask for some of it to be occupied by me, or given to me? Why would I ask for even a small piece of the world’s heart? I thought: I’m not going to promote this. I’m going to disappear and find some other function for me in this world. I had those thoughts and fantasies, which is its own kind of narcissism, and then I had to accept that I still had to go about my life, and I had to carry on just as everyone else has carried on in times of war and terrible conflict.

In the face of a pretty violent, hateful, white supremacist state that does not necessarily care if I live or die, I’m going to have to try to live. To live the best that I can. I have to try and do the things that make me want to continue living. I still don’t know if that’s a cop out, or if that’s massively delusional. If that’s useful to no one but myself, or if that’s not even useful to myself. But that’s what I’ve decided to do.