As Pearl River Mart prepares to close its doors, why the store’s godchild doesn’t want it to be “saved”

December 15, 2015

When Pearl River Mart announced plans in April to close its massive store in Soho, a collective spasm of grief shot through social media: from the usual “Noooo!” tweets to recriminations against the rent-hiking landlord, to harangues against gentrification. On the feminist site Jezebel, one commenter lamented, “[I]f this continues, NYC is just not going to be NYC any more. The amount of individually owned quirky places that have closed gets worse and worse every day.” Dot-com luminary Anil Dash—generally not one to bemoan the pace of social change—tweeted, “I almost never do the “sad about an NYC institution closing” tweets, but this one… sigh.”

Shoppers seem to mourn the prospect of the iconic storefront vanishing from the Broadway streetscape; the lightbox display of artisanal paper parasols and cloisonné exotica has long stood as an unofficial landmark—now it’s a fading film still of a New York strip awash in Plexiglas and flat screens.

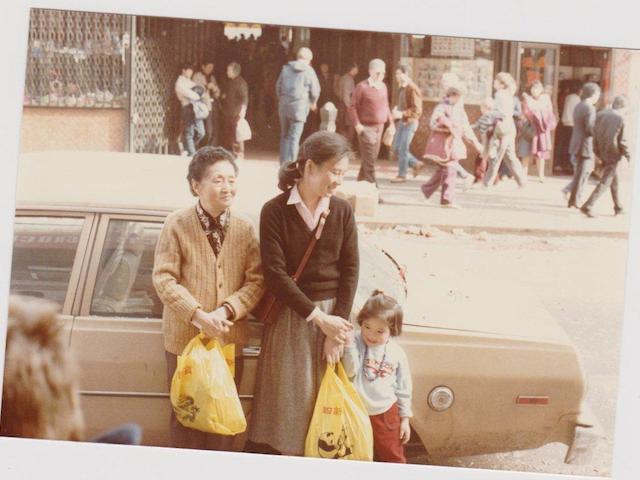

But I see the storefront from different angles. I was born and raised in the early 1980s nearby on Grand Street in Soho, bordering on Chinatown. I’ve witnessed the surrounding socio-economic terrain get plowed and mined into a developer’s paradise since. In many ways, Pearl River’s ascent, decline and displacement track the trajectory of the urban landscape of my youth.

Against the backdrop of Manhattan’s ravenous bargain-hunting bustle, my parents’ hands etched out a little sanctuary for a slower shopping experience, in which consumption is less about acquiring than about savoring. Still, when I peer into the front window, I don’t see a quirky product display. I see my parents’ craft. As the managers of the company, they’ve been designing the displays as long as I can remember, taking hours, sometimes working through the night, to festoon the space with an ensemble of cheong sams, calligraphy pens and Ming porcelain teacups.

Pearl River Mart’s display window refracts through all the facets of Chinatown’s modernization. The store was born on the cusp between old and “new” Chinatown in the early 1970s. My father founded the store as part of a new vanguard of young radicals who flocked to the neighborhood to connect with their cultural roots and to disrupt the community’s political insularity. While others ran radical poster workshops and Marxist study groups, my father built a “Friendship Store,” on a hunch that the diplomatic thaw between Beijing and Washington would soon liberalize trade relations. That first wave of Sino-American imports helped Pearl River relocate to an elevated two-storey, fluorescent-lit bazaar on Canal Street. After that corner became engulfed in Gucci knock-offs and seedy tourist trinket stalls during the 1990s, the store got ready for a change of scene.

Against the backdrop of Manhattan’s ravenous bargain-hunting bustle, my parents’ hands etched out a little sanctuary for a slower shopping experience, in which consumption is less about acquiring than about savoring.

With our final move to Soho in 2003, the store simultaneously shed the pleather baggage of Canal and Broadway and turned one of Manhattan’s hottest retail strips into an upscaled Chinatown colony.

* * *

The move might have looked like selling out from the outside; as a lifelong resident I generally cast a skeptical eye on ethnic commercial fetishism. But when I asked my father about the relocation, he described a more subtle calculus: After a decade on the outer limits of Chinatown, he observed, “the basic customer was from Soho already.” The business had matured into a key destination for fashion magazine editors who regularly featured our products in their recommendations for buying the “budget” version of runway couture. And quite a few film set designers and event planners have made creative use of our paper mâché New Year’s dragons or spherical lanterns to create their perennial bricolages of orientalist kitsch.

These customers were not my parents’ people—they were mostly whites, well-heeled tourists, and second-generation Asian Americans. But despite this, or because of it, they were Pearl River’s natural niche market: appreciative of tradition but open to anything. They may have been more cosmopolitan, but their conspicuous consumption of conscious tackiness meshed well with my parents’ reconstructed revolutionary sensibilities. “The way we developed our store is closely related to the Soho development,” my father reflected. “Closely synchronized.” My parents were chasing the market and also gravitating toward a more diverse, eclectic community of shoppers.

“Before in Chinatown, our basic customers were new immigrants,” he added. “New immigrants can only consume certain items. If you want to open up in a different area, you have to get new customers or you can’t get new support…. Coming to Soho was very natural.”

Some things would never change. The wages and price tags stayed surprisingly modest despite the higher-income district, and the store retained its Chinese staff, with a cadre of veteran workers alongside a few part-timers. The characteristically brusque (i.e. non-English speaking and nary a “Hi, May I Help You?”) customer service was noted in Zagats. Yet the store never adopted the high-turnover, on-call retail staffing system that has become standard in many low-wage chain store operations.

Yet with the Soho-ification of the store, there was a notable demographic shift in the foot traffic. Just as many neighborhoods “turn” as they gentrify, the customer base flipped from mostly Asian immigrants to mostly whites with a steady stream of tourists (including a few middle-class Chinese visitors who were perhaps titillated by the East-West cultural boomerang).

The Soho transition in the early 2000s was a business move for my parents, but for the city, it was a reflection of a socio-economic tectonic shift: My parents caught the tail-end of an age of relatively affordable retail space, when a small business could still be a local cultural giant. Pearl River arrived when the classic record emporium Tower Records still stood a few blocks up on Broadway, staving off the digital download frenzy; Canal Jeans and Pearl Paint clothed hipsters and got them through art school on a shoestring. But soon the art-school set gave way to the high-powered creative class. Bloomingdale’s and Sephora overtook the Guggenheim and chain pharmacies and Starbucks caulked the remaining cracks. The short-lived sweet spot of flourishing grassroots trading rapidly yielded to designer labels and venture capital.

The Soho transition in the early 2000s was a business move for my parents, but for the city, it was a reflection of a socio-economic tectonic shift.

When people think of gentrification of neighborhoods, they assume the fishmonger and pushcart vendor are the commercial analog to displaced working-class tenants, but in truth the entire retail ecosystem is upturned. More established small businesses, including restaurants and mid-range retail shops and specialty stores, buttress the scaffold of a local economy. When the petty bourgeois substrate collapses, it opens the door to an invasion of franchises with no indigenous links to the community. That paves the way for an endless succession of heavily capitalized brands with little incentive to reinvest in the community’s infrastructure or tax base.

Pearl River’s struggle to stay afloat on Broadway was surely the product of many economic factors—the Great Recession being perhaps the most immediate. But it also shows how the trope of “mom and pop shops” being evicted doesn’t quite capture the nuanced transactions entailed in the “bleaching” of neighborhoods.

The latest rent hike would roughly quintuple the already astronomical rate of over $100,000 per month. My parents would have to squeeze vastly higher revenue from three packed floors: the main level featuring apparel and folk novelties, a home section offering colonial-style replica furnishings, and a basement of plebeian accoutrements. But the black lacquer bento box, the jade see-no-evil monkey figurines, the rattan birdcage—while priceless to our old customers—carry a real market value of only a couple of lattes. But Pearl River stands between developers’ speculation and the savvy of New York shoppers. It sets its prices to cater to those who can spot a good deal, but faces a wildly inflated rental market. So the enterprise gets jerked by two opposing cost curves: the real estate bubble versus an increasingly rare bargain brand.

But respecting the intuition of the urban consumer is embedded in Pearl River’s business model. And it may be what makes the store “uncompetitive” in a neoliberal marketplace. It’s not the kind of store built for digital commerce and gamified marketing strategy. You don’t really know why you want anything here until you grasp it in your palm. And when the doors close, the loss will be palpable.

* * *

As I took stock of the store’s history during these final weeks before the lease runs out, I realized that my sense of the store’s legacy has always been bound up in my parents’ biography. I knew I should peer more closely into the lives of the staff who made the store run. Though there’s a chance the business might continue under different ownership in a stripped-down form, the current operation will extinguish what might be the longest-running job some of them ever had. Like many customers, I regrettably had given them less thought over the years than the items the store marketed. Maybe it was the dazzling alternate universe engendered by the dazzling product array that made me push the banal human elements of the business into the background. My parents, as managers, don’t give particular publicity to their mundane operations. A routine comment from shoppers and critics is that the staff seem standoffish or uncommunicative. That may be a product both of cultural and language difference and of the sense that their job is to keep the place running, not create ambiance or woo customers with the charm that upscale retail sales workers are trained to perform, often painfully.

When people think of gentrification of neighborhoods, they assume the fishmonger and pushcart vendor are the commercial analog to displaced working-class tenants, but in truth the entire retail ecosystem is upturned.

But now I was taking stock of our social inventory. So I had my first long conversation with Wilkie Wong, a lifelong staffer who started working in Pearl River when I was a baby and now heads the wholesale division as vice president. Wilkie started as a part-timer when attending Seward Park High School in the early 1980s. He grew up in the store, like I did, and went from a shy immigrant teenager to a young father.

When he was younger, he said, “Your mom knows I have three younger sisters, and from time to time she would say ‘how are they doing?’… I guess Pearl River is a family-oriented business.” Some workers started out single and stayed at Pearl River throughout the years, going to college, getting married, having children and then grandchildren, he recalled. “I worked long enough to see the whole thing.”

As the store winds down, it’s hard for him to imagine working somewhere else. “A lot of uncertainty,” he said. “When your mom [first gave me the news],” he said he thought, “I will tell myself, ‘Go look for a job.’ At this point, I still don’t know yet.” Looking ahead, he told me that, for both him and the company, “I don’t want everything to be wasted. So what I learned here, I hope I can utilize that for the future. Whether I can be successful in that, I don’t know.”

The response of some staff appears to waver between denial and resignation. Weeks after the announcement of the pending closure, one longtime middle-aged employee told me that she was sure Pearl River would never close because my parents would simply never let that happen. New York — their New York, and the New York of so many longtime customers — is unimaginable without it.

My parents, overall, seem more accepting of Pearl River’s inevitable end (at least in its current incarnation) than some fans and even workers. For those who experience it only as a place to shop or to work, Pearl River is a self-contained universe suspended in the social ether; it couldn’t just melt away, could it?

Not that my parents haven’t thought about keeping the company going in a different form. They’ve been approached by several entrepreneurs seeking some kind of potential business partnership. Some have offered cheaper, smaller retail space in another area. So far, nothing has crystallized into a concrete proposal, and as the end of the lease nears, they are not optimistic about the “right offer” coming along. And in any case, after a 44-year career, my parents, as employees, are facing the inevitability of retirement.

For those who experience it only as a place to shop or to work, Pearl River is a self-contained universe suspended in the social ether; it couldn’t just melt away, could it?

For me, the lingering uncertainty over the store’s future is more jarring than the idea of Pearl River completely disappearing. What made the business such a fixture in the urban fabric was the way it knitted together kinetic energy and grassroots coziness. True, the inventory and design have constantly evolved: On Elizabeth Street the store featured enamel dish ware and People’s Liberation Army posters, while the Soho space features bamboo shoji screens and contoured postmodern water fountains. What never changed, however, was that it had a place for everything. You could walk in and find both what you were looking for and something you didn’t know existed, and they’d both magically find their way into your shopping bag without a second thought.

Today’s retail shops embody a different kind of newness, the kind designed not merely to enchant—the way people may get hooked on our powdered paper or never forget the scent of their first bamboo steamer—but rather, to prod and awe, and to define what’s in and who’s out.

A recent City University study by Sharon Zukin and other researchers on gentrification patterns in New York City noted that in “hot” downtown areas, like the hipster enclaves of Brooklyn and the Lower East Side, the “upscaling” of commercial spaces tends to be consciously edgy, with a boastful emphasis on quirkiness and urbanity. Even when the “old” is reappropriated, as in homely Euro-themed creperies or Tibetan paraphernalia shops, tradition is given a postmodern spin so that the consumer who peeks through the window is not just intrigued but awed, and perhaps a bit intimidated. “New shops, cafés, and restaurants,” the researchers wrote, “are visible public space; they… reproduce the culture, that creates a new sense of place.”

I think that’s what I fear about Pearl River becoming something new: the idea that this modest cultural pillar will become a store that “creates a new sense of place,” rather than grow with its environs. It’s a subtle distinction, but one on which the fate of a city may hinge: Is the boutique a place of commerce designed to “disrupt,” to generate tension for tension’s sake? Or is the corner shop playing the harmony to the urban discord?

Maybe Pearl River could be purchased as a brand, to serve as a vehicle for remapping a micro-economy and upping the local property values; maybe they could put it in a strip mall somewhere to give it a bit of ethnic “character.” But that wouldn’t be a real continuation of its legacy; it would be flattening it into commercial signage to proclaim that some entrepreneur had “arrived.”

I think that’s what I fear about Pearl River becoming something new: the idea that this modest cultural pillar will become a store that “creates a new sense of place,” rather than grow with its environs.

I try not to be unnecessarily pessimistic. There could be a next generation of brick-and-mortar retail in Manhattan that embodies the ingenious commercial alchemy that imbued Pearl River. But I don’t know if, in today’s Manhattan, that can ever be embodied again in a single iconic location. Pearl River’s storefront won’t be the only such space that has vanished from the landscape in recent years. I could be talking about the raunchy goth club, or the bodega that hawked cigarillos and smoker’s gum; or the stuffy laundromat under your first apartment that once served as a tenants’ town square.

But this is not a call for “preservation.” There are many valiant attempts to save local small businesses to protect low-income neighborhoods from hemorrhaging local jobs, affordable housing stock, and indigenous color. There are legislative proposals to stabilize rents and cordon off beloved mom-and-pops from predatory developers. While such measures may be helpful policies, I don’t think New York itself needs “saving.” As Marshall Berman predicted, the march of progress and the collapse of civilization are eternally in tension, and residents are perennially declaiming one or the other. Through Gotham’s eternal churn between solidity and fluidity, it will stay open for business.

And that’s why I’d rather see Pearl River bow out gracefully than be resurrected by some magical angel investor. The city has always been locked in a constant struggle for its soul, but that doesn’t mean every awesome second-hand shop or legendary bagel place needs to be a battleground. To the extent that its denizens can shape, revitalize, protect or reenvision their landscape, we don’t need to fixate on certain spaces, because nothing is fixed about this place. Stores come and go. There will be clashes and tensions, but the city is framed by those interactions, not threatened by them. The one thing we do need to protect is the idea — which has always been a crazy and endangered one — that there’s room enough for all here. This is one place where a store window can take in the whole world.