How does one deal with anti-blackness within the family? One Bengali writer is finding out the hard way.

June 17, 2016

I exhale the smoke from my cigarette before throwing it on pavement on 135th Street, as cool water from a rusty fire hydrant splashes on my feet. I’m surprised none of the New York City police officers have made a fuss about a fire hydrant spewing water onto the street. The cop cars were fixtures in the area, a detail that evoked mixed reactions from my parents.

“Bad people live there, lots of kala [kala means black in Bengali] people,” my dad warned me after I told him I was moving to Harlem.

He preferred I stay in The Bronx, where my family has been living for more than a decade. But a generous opportunity allowed me to live in Harlem for the summer, all expenses paid and I felt wasteful passing it up.

My parent’s discomfort about my moving out was rooted in two things. First, nice Bengali girls don’t move out of their parents’ house until they are married, especially if they’re living in the same city as their parents. The second reason is more complicated.

“Can you show us houses near where white people live?” I remember my mom saying to our realtor years ago. My 12-year old face burned with embarrassment. It’s been about eight years since my family and I moved to New York from Bangladesh and I was used to “translating” my mother’s English, much like many other immigrant children I knew. This didn’t always mean literal translations of Bangla, but softening the bluntness of her English. In other words, saying what you mean without actually saying it.

“She didn’t mean that! Her English is still a bit shaky… We’re just looking for a more suburban area,” I said in typical first-generation immigrant kid fashion. Much to my shock, the realtor, who was unfazed by the encounter, responded that she would do her best. I wondered how often people asked her that.

“The conversations I have with my parents about why black lives matter, why we need to hold police officers accountable, and the system that upholds them is is always a difficult one, but I’m going to keep trying.”

After my mom’s first eight years of living in New York City, she observed what seemed to her is a fundamental truth: White people have nice things. In phone calls back to her sister in Bangladesh, my mom explained that white people are the ones with the brand new cars, duplex houses with bright green lawns, and they even monogramed their nice things with their names!

The concept of a suburb went right over her head, too — the fact that people would actually want to live farther away from the city. One time we drove past a gated community in Long Island and she lost it. She couldn’t look away from carefully manicured lawns, sprawling pools, and absurd golf courses (she couldn’t understand why anyone would waste so much land to push a tiny white ball into a hole).

In this country, upward mobility for immigrants has always been associated with how quickly one can adapt to whiteness and somewhere along the line, that also meant internalizing anti-blackness. For many South Asians, this meant trying to erase one of the most beautiful parts of ourselves — our sun-soaked, coconut-colored, dark skin.

“If I eat this banana, will my skin become white like yours?” my 5-year-old sister says to my mom as she begins to peel the patchy dark skin of an overripe banana. It was a heartbreaking moment to hear that my little sister already feels discomfort in her own skin, but I can’t blame her when everything around has never suggested she should feel otherwise.

My own skin color wasn’t much lighter than hers either but at this point, I had grown indifferent to unsolicited comments. But watching my little sister graze her fingers over her skin, wishing it wasn’t hers was painful. I’m used to shrugging off unsolicited comments about how I could “improve” my skin from relatives, but watching the same trauma begin to unfold for my baby sister was a different story. It was the first time I realized why I needed to confront my family about the trauma we pass to each other and getting through those difficult conversations.

Several years after the banana peel incident, I find myself confronting the same issue again in another form. It’s 2014 and a jury ruled that it would not indict New York City police officer Daniel Pantaleo for putting Eric Garner in a fatal chokehold, which led to countless demonstrations across the country. It was comforting to know that I was not alone in my frustration and that hundreds of other people were fed up with our justice system placing little to value on black lives.

After coming home from one of these rallies calling for justice for Eric Garner, my dad ushered me in for a talk that I didn’t expect. He disapproved of my outspokenness of my politics, especially when it came to attending rallies. But this time he wasn’t angry like I had expected him to be. Tiny droplets of water were filling up the corners of his eyeballs, which struggled to be propped up by his tired eyelids.

“Listen ma, they killed that man like he was an animal and they’re never going to take responsibility for it,” he told me. “Nothing you do will change that, they will only come after you, too.”

I spent a lot of my life bearing witness to my dad’s heightened paranoia, a product of post-9/11 Islamophobia where our community became targets for surveillance and punching bags for conflicts we had nothing to do with. This time, my dad’s words stung me with a sense of overwhelming self-awareness. He knew what happened to Eric Garner was wrong but was unwilling to cross the confines of what made for the “good” immigrant.

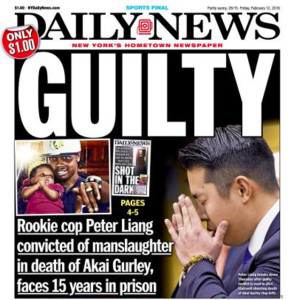

After NYPD policeman Peter Liang’s manslaughter conviction and the protests within the Chinese American community denouncing the court’s decision that followed, writer Jay Caspian Kang aptly describes the uneasy dissonance about justice and assimilation in the Asian American community.

“As a rule, we seldom engage in the sort of political advocacy and discourse that might explain, or even defend, our odd, singular and tenuous status as Americans. This is how it has always been for immigrant populations who believe, rightly or wrongly, that they are on a quick march toward whiteness,” he wrote in an article for the New York Times Magazine.

I try to explain to my dad that we wouldn’t have been able to immigrate to this country if it wasn’t for the work of the civil rights movement, if it wasn’t for people fighting for justice about issues that don’t directly affect us. He calls me an idealist and shrugs it off.

“I worked really hard to get us all here,” he says to me, in a default guilt-inducing immigrant-dad manner. To him, our citizenship was always going to be conditional so it’s better for us to look the other way when injustices happen to other communities (sometimes even in our own).

We’re at a standstill.

I don’t know how to explain white supremacy in Bangla so I give up. And so the conversation ends in a familiar way, with the both of us frustrated with each other. To him, pushing the boundaries of the status quo meant giving up everything he worked for and he wasn’t willing to risk it.

I understood what he means, but buying into acceptability politics will not be enough to protect us. The conversations I have with my parents about why black lives matter, why we need to hold police officers accountable, and the system that upholds them is is always a difficult one, but I’m going to keep trying.

Sometimes showing up means staying at home, where the work can be the hardest.