Faced with the sudden death of a loved one, Muslim immigrants — after a secular lifetime in America — cross this final frontier of assimilation.

June 29, 2017

We had a hard time finding parking at the mosque that morning. Looking back, that should have been the first sign we were about to walk into unfamiliar territory. None of us had ever been there before and we were encapsulated in the time warp that grief creates, so the date, the day, didn’t occur to anyone. It was Friday. Of course the whole community is here for weekly prayers. This is their routine, their ritual. We are the interlopers, not them.

Our necks stiffened as we walked into the hallway on the first floor where we began to take off our shoes and place them on the cold metal shelves. This part was familiar. No matter where you are in the world, no matter how pious or blasphemous, when you walk into the mosque, you take off your shoes. Manners. Respect. Each of us brought a scarf to drape over our heads, the ones we usually use to shield ourselves from the brisk air, but one of the aunties had brought seven soft, mesh, black veils. It could have been a bride’s dressing room before the wedding, when bridesmaids prim and fluff for the big moment.

But once we were dressed, we didn’t walk down the aisle, we walked up the stairs in single file toward the women’s section. The narrow room was already lined with ladies sitting on the floor. They were not wearing black. It was an array of colors and designs representing the different corners of the world from which they came. Bet the Pakistani woman never imagined she would be haunch to haunch with a woman from Senegal, but that is what Muslims do in America they go to that mosque because it’s the only show in town.

“All of us immigrants, we knew what it was like to be aliens in America and many of us had shed our green skin and antennae to assimilate long ago. But we were aliens again that day as we reached for a place of cultural comfort that turned out to be anything but.”

But as secular, first-generation immigrants, we have no death rites. Part of assimilation, for us, became shedding all ceremony. We learned to mark big occasions privately. We could not adopt American rituals – that would just be false. We could not adopt Muslim-American rituals – that too would be false. There are immigrant communities who know what they will do when there is a death. There is an established set of rituals based on decades of being astutely Muslim in America. So where does that leave us? The ones who reside, often comfortably, in the in-between?

The regulars at the mosque immediately recognized that we were there for something entirely different. They sniffed out Ali’s grieving mother and seemed to be drawn to her, almost as if she was a celebrity. That bizarre hierarchy of who was closest to the deceased reared itself throughout the day. Is that the mom? Akh, akh, that’s too bad. Who is that? Was he married? Ohhhh, is that the girlfriend? Is that the NEW girlfriend?

We squeezed ourselves between the devout and waited for namaz jome to begin. It was at this point that the realization dawned on us, it was not just Friday prayers, but there were two other men being buried that day. Had no idea who they were. Still don’t. Even still, the imam didn’t seem to say anything. He didn’t know Ali, but he knew it was a sudden death. What was he supposed to say? He darted off thoughts and prayers about this and that and quickly moved on to logistics: If you want to sign up for basketball camp, it starts Saturday, so don’t forget to add your name to the list by the door. At this point, even Ali’s mom, grief-stricken and virtually unable to move, stood up and left.

We met our men outside. They refused to go in. Everybody knew Ali was staunchly against religion. Not just slightly, but veins popping, teeth bared, anti-religion. You couldn’t get through a conversation about it without half-expecting him to grab his chest and pass out. That’s how he won so many arguments, it always seemed as if his health could possibly be at risk.

Nevertheless, here we were. Ali had been unceremoniously shot in the head in a loft in Bushwick in Brooklyn five days earlier. He was killed, along with two other musician friends, by another Iranian musician who then shot himself. Now here we were, lined up outside a mosque in Dallas, Texas, where he grew up.

We were under the impression that following the “sermon,” we were going to be led to a smaller, quieter room. At this point the men and women, about 14 of us total, walked back in and lined the hallway as we waited to get into the room. Total aliens again. All of us immigrants, we knew what it was like to be aliens in America and many of us had shed our green skin and antennae to assimilate long ago. But we were aliens again that day as we reached for a place of cultural comfort that turned out to be anything but.

After a long wait in the fluorescent light of the hallway, the doors opened and we relaxed a bit, thinking we could sit comfortably in our grief for just a moment. The hall they had promised turned out to be an empty gym. A large gym with black chairs stacked high against one wall. Guess this is where basketball camp will start on Saturday. OK. We began to take down a few chairs for ourselves, but one of the mosque’s administrators informed us that wasn’t an option. OK. They ushered the women into a loose line in the middle of the gym and the men to the front. OK.

“Thirty years after moving to this country, after he sang pitch-perfect and beyond with the best of them… after speaking perfect English in class and on the street, how were we still the ill-adjusted immigrants who first arrived here? Will we always be culturally slightly off-key? Even in the end?”

Moments later, the people started to file in. Hundreds of people, row after row, ushered in to that gym in a matter of minutes. We soon found ourselves jostled this way and that as total strangers filled the space and tried to touch Ali’s mother. My family had known Ali’s for decades, and in our twenties, Ali and I were surprised to find ourselves in a relationship that went on to last for seven years. So, at five feet tall and ninety pounds I found myself acting as a bodyguard for his mother in the mayhem, there was no time to do anything else.

The din in the gym grew and soon pine caskets floated into the room, like crowd surfers over a mosh pit. He was a musician who worshipped the stage; at least that part was congruent. What the hell is going on? Which one is Ali? Ali, which one ARE you? Never mind, this woman is about to run me over in order to get to the grieving mother. And just as quickly as the coffins bobbed into the gym, they bobbed out. OK. Now what? Get to the cemetery.

Surely, things are going to slow down now. Yes, in Islam, we bury the dead as soon as possible; there’s no embalming fluid, no open casket, no makeup. The first time I went to a Christian funeral in America, I was just 5 years old, and terrified by the bloated body of the man looking up at me from the casket. So much makeup. In Islam, the body is washed and put into the ground. In Ali’s case, the medical examiner in New York worked quickly to get his body back to Dallas. But, still, surely now we’ll have a minute.

Getting out of the parking lot was yet another nightmare because all those people in the gym now rushed to leave. In a daze, every step was still surprising. It took us all of 17 minutes to get to the Muslim section of the cemetery and they had already begun the burial. With a bulldozer. A loud bulldozer like the one that would wake Ali and I up in our south Brooklyn apartment years before, when we still clung to one another’s warm bodies. I gave up at this point. All of his American friends joined us at the grave and we watched as his slight body, wrapped in a white cloth was dropped into the Earth. People touched his toes before he went in. I turned my back. Ali, what are they doing to you? Can you believe this?

That’s when the bulldozer started throwing dirt on him. I peeked. I went up close, only to find that there was so much screaming, wailing, sniveling and inappropriate gossip closer to the hole that I would be better off with my back turned. His parents needed a barrier to the spectacle anyway. It was too much to bear. They didn’t need any more water. No amount of water was going to wash this away.

The same auntie who provided the veils was apparently also some sort of self-appointed pharmacist who kept trying to push pills on the aggrieved. The chaos was surreal and all I could do was stand completely still in the hope that my stillness would somehow be contagious. Slow down. Please, slow down. Ali, can you believe what they’re doing to your body? Can you believe it?

“All the blemishes and bruises of assimilation rear their ugly heads again in this final frontier. We hadn’t reached this part yet. We did school and work, we managed mixed weddings, Christmas, New Year’s Eve, Norooz, Thanksgiving. But not this. “

How did such a force of life have such an absurd ending? And I don’t mean the senselessness of his violent and sudden death, but the awkwardness of the days that followed. Thirty years after moving to this country, after he sang pitch-perfect and beyond with the best of them in Memphis, Richmond, Birmingham, Los Angeles and every pit stop in between, after speaking perfect English in class and on the street, how were we still the ill-adjusted immigrants who first arrived here? Will we always be culturally slightly off-key? Even in the end?

On the opposite end of the spectrum, when my maternal grandparents passed away, we put on our black clothes, but otherwise barely even marked it here. They were both adamant about dying and being buried in Iran. Here, we just got together, without ceremony. No eulogies, no repass, no slideshows. It was almost as if we didn’t know what else to do. Most of us couldn’t make the trip. When my father’s father died many years earlier, not even he could make it to Iran since we did not have our green cards yet. I barely remembered my grandfather, and even as a young child apologized to my parents for not being moved to tears.

Now, as an adult, I felt the loss compounded once again by a lack of ritual to fill the void.

After 30 years, we are still in the wilderness. All the blemishes and bruises of assimilation rear their ugly heads again in this final frontier. We hadn’t reached this part yet. We did school and work, we managed mixed weddings, Christmas, New Year’s Eve, Norooz, Thanksgiving. But not this. Especially when there is a sudden, violent, young death. When there is no time to think, reflex kicks in.

We reflexively went to the mosque.

Back in New York, the ceremony swung to the other end of the continuum. A massive concert at Brooklyn Bowl, a music venue where I had danced through many nights, was less about grieving and more like an unruly party. The alcohol-soaked floors, the dark club, the flashing multi-colored lights.

After the shooting was in the news for weeks, hundreds of people came and went. Hipsters with asymmetrical haircuts, older Iranians dressed in black, reporters, they all showed up for the blow-out. I had thought this might feel a little closer to Ali and the life he had created for himself, but it wasn’t. It was still too loud and too fast. The nature of his death propelled us to extremes and exposed the raging double consciousness we thought we had tamed.

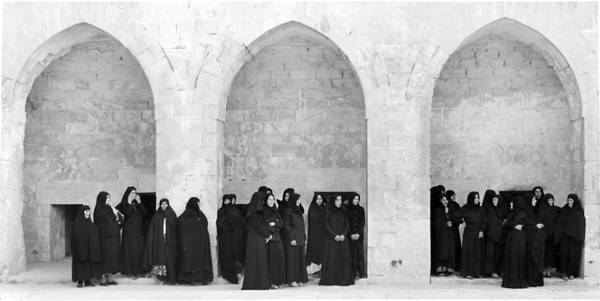

Copyright for all photos belongs to visual artist Shirn Neshat. Her photos appear here courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.