How this Brooklyn staple has served to bridge two cultures

August 27, 2019

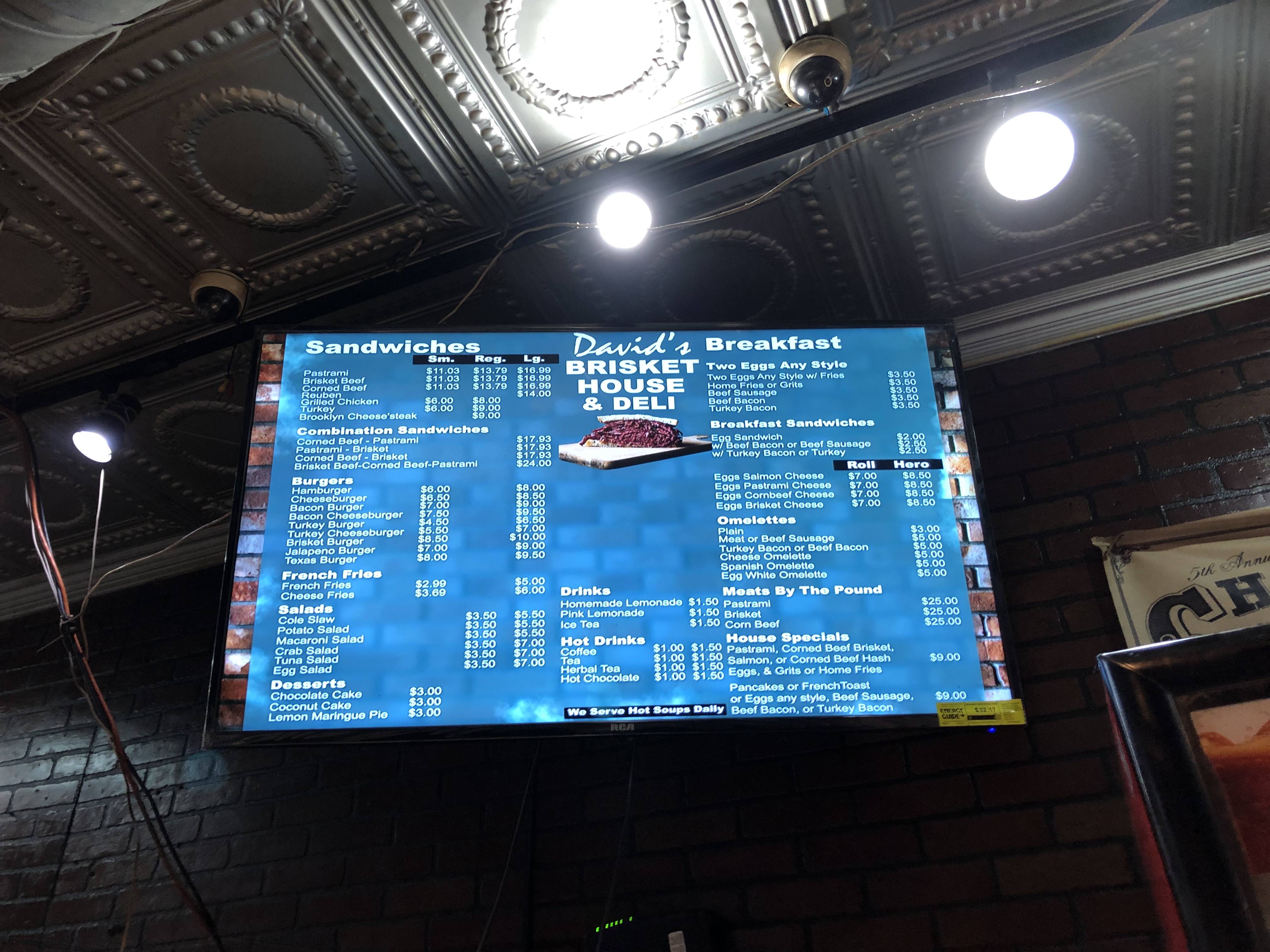

It is 11 a.m. on a Monday morning at David’s Brisket House in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn and business is well under way. All of the booths and tables at the small deli are occupied, and the fragrant smells of brisket, corned beef and pastrami fill the air. Hungry diners are tucking into fat doorstop rye bread sandwiches with dark pink slices of meat dotted with bright gobs of yellow-brown mustard spilling out over the edges.

In the kitchen, a slight man single-handedly prepares orders – slicing cooked meat, frying eggs, whisking up an egg, cinnamon and milk batter for French toast, and overseeing at least one heavy-duty pan of simmering brisket. Dressed in a short-sleeved turquoise blue polo shirt and long red apron the man moves deftly across the generously-sized kitchen, which is slightly larger than the eating area. His name is Riyadh Ghazali and he is the proprietor of the deli, and the third line of Muslim Yemeni-Americans to run the traditional Jewish deli.

After briefly experimenting with additional food lines, he tells me people are only interested in one thing: the fragrant cured red meat which the deli has been serving up for more than half a century.

“When I took over, I kept it the way it is,” said Ghazali. “I tried my luck in catering to people that don’t eat red meat. At one point, I was doing fresh turkey here. It didn’t do that well. I started doing a juice bar. It didn’t do that well. I did a salad bar. It didn’t do that well. I started doing steamed vegetables, cabbage, potatoes. I was doing things I was familiar with. At the end of day people come in and they just want pastrami and corned beef. If they want something else, they tend to go somewhere else.”

The recipes, the secrets to the brisket’s house success, are closely guarded. He has had offers from as far as England offering to buy the recipes and to franchise the business, but he has refused them all. All he will tell me is the is that the corned beef is prepared with coriander, mustard seeds, and cloves. At the back of the kitchen, a huge piece of brisket — simmering in a secret mixture — bubbles vigorously on its own stove.

Ghazali, who was vegetarian when he first joined the business, has long left his herbivore ways behind. “I started snacking here and there. It’s very addictive, if I’m honest with you,” he said.

Running a food business was not a path he thought he would ever tread. The business administration graduate worked briefly at UBS, but didn’t like the corporate world. When his cousins called him up in 2015 because they were struggling to run the business, he said he packed his clothes and came. Riyaadh has been instrumental in turning it back into the thriving business it once was.

Urban Legend

Lore has it that David’s Brisket House was originally owned and run by a Muslim and a Jew. But Open City can confidently say that this is not the case. While there was a Muslim-Jewish-run donut shop on the same street, David’s Brisket House was originally founded by two Jewish partners who sold the business to a Jewish businessman, who then sold it to an Arab Muslim to pay off his gambling debts.

The original founders, Zolle and Barney, set up the deli in 1949 on Nostrand Avenue. The business was so popular, there used to be lines down the street. When they came to sell the business, they had a contractual requirement that the business only be sold to Jews. In 1976, they sold it to a businessman called Henry, who had a gas station in New Jersey and knew little about the food business.

Ghazali’s uncle, Hamood Almass, who bought the business from Henry, recalls that Henry’s proprietorship only lasted six months because he rang up gambling debts. “The deli was only open five days a week, and he [Henry] would go away on the weekend — sometimes to Las Vegas, sometimes to Atlantic City,” Almass recalled. Whatever he made, he spent it gambling. After a while, business went downhill. He owed thousands of dollars.”

Henry came over to the donut shop where Hamood worked and asked him if he would be interested in purchasing the business for $15,000 in cash.

Almass said, “I asked my friends for help. I told my business partner in the donut shop, ‘It’s time for me to go.’”

Mani – A Chance Meeting

Photo by Syma Mohammad

When Hamood Almass moved to the United States from Yemen in 1973 at the age of 29, he did not know what a donut was. Little did he know he would be running a donut business a few years later.

At the ripe age of 86 years, Almass is a striking, energetic man with ruddy cheeks. When we meet, he is wearing a blue and white letterman jacket. It takes three months to pin him down after my initial request because he is overseas in Yemen. When I first speak to him on the phone, he is a reluctant interviewee, telling me that I should speak with his nephew Riyaadh Ghazali.

At Ghazali’s bequest, he agrees to be interviewed. When he arrives at the brisket house, Ghazali pats him on the shoulder and instructs him to “tell her everything.”

An engaging and detailed storyteller, Almass recounts that he initially worked in car factories in Michigan when he moved to the U.S. After he got laid off, he went to California for six months. A friend called him and told him that New York was a good place to find a job, so he moved to the city and started working at a grocery store in Fulton Street in BedStuy.

One day he walked past a donut shop on Nostrand Avenue, a block away from where he worked and the current location of David’s Brisket House. “I had never seen a donut before. I didn’t know what a glazed donut was,” he recalls. His decision to go inside was a life-changing one.

“The owner was a Jew from Yemen. I didn’t know he was Jewish. He had a big moustache. He was staring at me and then said, ‘Assalamu alaikum.’ It was 1974. Nobody knew what ‘Assalamu alaikum’ was in 1974. He said, ‘How are you doing, brother? Where are you from?’

“I said, ‘Yemen.’

“He said, ‘I’m Yemeni too. What are you doing here?’ He gave me a cup of coffee and a donut. He said, ‘You have to eat it.’

Both men discovered they were from the same town in Yemen, and the seeds of a friendship that were rooted in a shared Yemeni heritage were sown.

“He then told me he wanted to dance to Arab music, so I invited him to come dancing with me and some friends.

Photo by Syma Mohammed

“When he turned up, the boss of the store where I worked, said, ‘Why did you bring him?’

“He [Mani] said, ‘I’m from Yemen! I’m a Jew from Yemen. I’m not going to lie to you. I love Yemeni people. I love Yemen more than Israel.’

“My friend looked at me and said, ‘You brought him here?’

“I said, ‘Take it easy, guys. He wanted to come. It’s nothing to do with politics. We’re friends.’

Later that night, Mani told his new friend to come to the donut shop the following day.

Almass recalled he went back to the donut shop during his break the next day, and Mani proposed they go into business together.

Almass initially declined, saying, “’I don’t know anything about donuts. Come on, man! I’m not going to go into business with you. I don’t have any money.’”

But Mani was persistent.

“He hounded me so much to be his partner. I told him if I went into business with him as a partner, we had two problems. The first problem was I didn’t know English and the second problem was I didn’t know anything about donuts.”

“He said, ‘Don’t worry about it.’”

Mani sold Almass half of his business for $7,000. Almass only had savings of $3,000, so Mani arranged for him to pay $200 a month until he had paid the remaining $4,000 off.

Mani then helped his business partner linguistically and culturally adjust to his new job. He wrote the names of the different types of donuts in Arabic so Almass could understand what people were asking for. He also gently helped Almass acclimatize to the culture shock of working with women – something that Hamood had never experienced before in Yemen or the U.S.

The bakery was open 24 hours a day and Hamood worked at night while Mani worked during the day. Sometimes they would both work together during the day.

After two years, Almass admits he was “sick” of donuts. When Henry offered Almass the chance to buy the brisket house, he leapt at the opportunity because he wanted a change.

Although he proposed the idea to Mani, he recalls Mani declined because he was too “scared” to go into a business he knew nothing about. The pair parted ways as business partners, but remained firm friends.

Although Mani is now dead, Hamood fondly recalls his old friend. “Mani was a good friend to me. He helped me a lot. He put me into business with three thousand dollars. What’s that? He gave me the business. I didn’t know what was going on. He gave me a lot.

“I appreciate him. Sometimes, I feel like he was my best friend in the world. He helped me when I didn’t know what was going on. He helped me with my English, he helped me with business, and he helped me how to deal with the public in a nice way.”

Who is David?

When Almass recounts the history of David’s Brisket House, I expect to hear about someone called David. After all, it’s a popular Jewish name. There is a Zolle, a Barney, a Henry and a Hamood, but no mention of anyone called David. Who is the mysterious David that the brisket house is named after, I ask.

Almass confesses, “I’m the one who developed David. When I came to the U.S., people found it hard to pronounce Arabic names. It was easier to have an English name. My nickname was David.” When HamoodAlmass bought the brisket house, the lawyer suggested he change the name of the business. So Almass used his nickname, ‘David’. Since then, it has been known as ‘David’s Brisket House.’

Zolle – Inheriting a Food Tradition

Although Almass knew the donut business inside out when he left, he knew nothing about curing meat. When he bought the brisket house, he also inherited a New York Jewish food tradition. Initially Zolle, one of the original owners, spent a month teaching Almass what he needed to know.

“It took me 30 days to learn from him,” Almass recalls. “I didn’t let him move one inch: I was like what’s this, this, this!

“He [Zolle] didn’t want to go. He got good pay. He got the equivalent of $350 a week from me.

“He stayed with me for a year. I learned a lot from him. After two years, I went to Yemen to see my wife.

“I asked Zolle, ‘Are you going to hold the business for me for ninety days?’

Photo by Ananya Kumar-Banerjee

“He said, ‘No problem, I’ll hold it for you.’

“When I got back I saw all the systems were working well and found out he didn’t want to stay at home with his wife.

“He said, ‘I like to work. I don’t care if I work for you for free.’

“But then his wife called me. She said, ‘Why don’t you leave my husband alone?

You’re not going to make him into a slave.’

“Zolle said, ‘I’m not going to move.’

“After six months, he said he had to go and he left and went to Florida.”

Life Beyond Pork

Islam and Judaism share many faith similarities, including guidelines around eating pork. For health reasons, both religions forbid the consumption of pork.

While Zolle and Barney and Henry all sold pork, Almass made a decision not to sell it when he took over. Instead, Almass decided to sell beef bacon and beef sausages. He also used beef fat instead of pork fat. He recalls Zolle told him: “You’re crazy.” Zolle thought it would affect the profitability of the business.

However, the decision brought unexpected benefits and an upturn in customers from the Jewish community. “The neighborhood used to be 100 percent Jewish-owned businesses. When I opened the business, more Jewish people came because I did not sell pork. People thanked me for selling a pork-free breakfast!”

While the brisket house has never been certified as kosher — even when the owners were Jewish — it started selling halal meat a little while after Ghazali took over. He says the move has seen an increase in Muslim customers from abroad, from places such as Germany and France. “They call us up and are excited they can get this food. They can either go to Katz’s deli but it’s not kosher. We are the only Jewish place that serves halal food.”

Location, Location, Location

The original brisket house – known as Zolle and Barney Corporation – was located across the road from the donut shop. After Mani closed the donut shop and relocated to Manhattan to open a clothing store, Almass bought the building, and relocated the brisket house to the site of the former donut shop.

Photo by Ananya Kumar-Banerjee

”

Food Lessons

It is a Saturday morning at David’s Brisket House. I am interviewing Almass at one of the booths, and the deli is once again full of diners. An old-time customer, Derick Brunson, recognizes Almass and warmly greets him. Derick tells me he’s been coming since the 80s. He would originally come to pick up lunch for his boss, but became a lifelong customer. He says, “After I tried it for the first time, I was hooked. I’ll never forget that day.”

Although the charming, indefatigable 86-year-old Almass retired in 2007, he hasn’t yet let go of the business. “I’m here all the time,” he admits.

“He’s always telling me what to do!” moans Ghazali. Almass shrugs his shoulders, “You can’t play a game with food. If you do, the customer won’t come back.”

“If I take five or ten dollars from you, and you don’t enjoy it, what’s the point?

“We’re not talking about clothes, or fashion. It should be an experience.”

However, it’s an experience that almost died out after Almass retired. Like many Jewish delis across the city, finding successors to take over a family business is difficult. I ask Almass what would have happened if Ghazali had not taken over.

“Honestly, it would have been finished,” he said.

I ask him if he is proud of his nephew for taking over and successfully running the business.

“Yes, of course,” he concedes with a twinkle in his brown eyes. It is hard-won praise from a man with exacting standards.

And with that, Almass gets up, and goes back to work.