Feminist organizers and writers reflect about what we have learned from one another about care, community, and survival in continuing to build solidarities towards collective liberation

August 30, 2021

“Communities sustain life—not nuclear families, or the ‘couple,’ and certainly not the rugged individualist.” —bell hooks, All About Love

The Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities project began in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. New York City was fully locked down, and the fear and anger that many of us were experiencing was raw and palpable. People were trapped in a rhythm of endless Zoom meetings and constant emails. It feels like those months passed in the blink of an eye, as blurry and wrenching as they were. As we wrote about solidarity across difference and worked on our reading lists, I remember reflecting on what kinds of histories this moment was activating in my body: a furious desire to manage my pantry, an inability to waste food, a near-constant anxiety about what to eat that reminded me most of a grandmother who lived through Partition. Months later, as we all began to come together in tentative and hopeful ways, I realized how we were living with our individual and collective histories of displacement, fear, and containment.

The people I loved and organized alongside had all been living with the ghosts of their ancestors, alternatively calling on them for hidden wells of strength and sinking deeply into pools of their trauma, passed down silently in their bodies. I have learned about how to give and offer kindness and grace from these people. As the months have worn on, my body and mind encountered new feelings of exhaustion and resignation. I have found an almost limitless appetite for rest, so that I might once again prepare for what joy feels like.

As I recognize the same feelings in those around me, I feel more than ever that our solidarity must be rooted in a love—of one another and of the idea of liberation—that allows us to do difficult things with softness and fortitude.

—Salonee Bhaman

As we continue to commit to building Black and Asian feminist solidarities, we don’t know all the answers. Solidarity is messy. This past year has been heartbreaking. Many of us have been reckoning with grief, loss, and death at different scales. At the same time, we have seen so much creativity towards imagining alternative possibilities. This compilation brings together ruminations, thoughts, reflections, and provocations from organizers and writers we have learned and built alongside this past year on the histories and knowledges they draw upon to practice feminist solidarities, lessons they have learned from organizing, and their visions for the future.

Feminist Histories and All Who Came Before

I draw on the histories and knowledge of my Black feminist antecedents, who in their quest to center themselves as they contended with misogynoir, transphobia, queerphobia, patriarchal violence, and anti-Blackness, were inclusive of women of color who were experiencing similar oppressions. If we are going to be frank here, they didn’t have to do it. They could have simply kept organizing intra-racially, which is most certainly needed. However, they connected the political dots to see how their own liberation was bound with that of others. They also recognized how white supremacy and its agents utilize destabilizing tools such as negative stereotypes and surveillance to prevent solidarity and unity across racial groups.

When conducting interviews with Ericka Huggins, Barbara Smith, and Denise Oliver-Velez for Black Women Radicals, they pushed me to expand my political imaginations and commitments. They pushed me to see the importance of being in community with non-Black women of color who wanted to be in community with me and other Black feminists. Reaching out to the Asian American Feminist Collective was me putting into action what Huggins, Smith, and Oliver-Velez taught me.

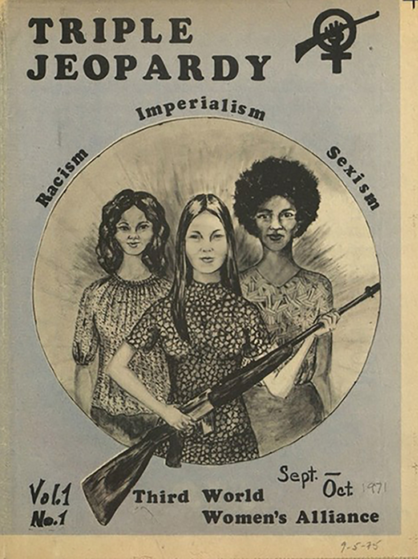

With this, I also think about and draw upon the radicalism of Black women activists such as Frances M. Beal of the Third World Women’s Alliance, Barbara Smith of the Combahee River Collective, and Stella Dadzie, Beverley Bryan, and Suzanne Scafe of the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent. They serve as a blueprint for me to understand what it takes for us to transform the world into a place we truly want to see—a place where white supremacy, anti-Blackness, transphobia, police violence, and other oppressions are abolished.

—Jaimee A. Swift

Zuri Gordon on learning from Third World feminisms

“The work started by 1970s feminist consciousness–raising groups is formative to my understanding and practice of solidarity. I want to bring back ‘third world woman of color’ as a political designation, which was introduced to the lexicon by the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA). When I look at the covers of the publication Triple Jeopardy, published by TWWA’s NYC chapter, I see my politics. The first issue shows three women of color in a circle with the words “racism, imperialism, sexism” bordered around them. That shared identity of third world women did something that’s been lost. Nothing else has that drama, that seriousness, that intention. That choice to work in solidarity against colonialism, imperialism, white supremacy; to take power and redistribute it to the marginalized, the sufferers, the survivors of U.S. imperialism here and abroad.

Their legacy and archive have shown me the need to prioritize creating a global sisterhood and to cultivate relationships across differences. I’m connected to the women of color who decide to become accomplices with other women, who know the power and threat we pose when we’re united.”

Zuri Gordon lives and works in New York City. You can follow her on social media at @saintzuri on Instagram and Twitter. Read Zuri’s poem with Cecile Afable “From the Other Coast with Love.”

The Difficulties of Solidarity and Being in Struggle

“We choose which ground to fight on for such a mix of reasons: what feels urgent, what feels hopeful, whether we have a good band of fighters to stand with, how much of ourselves we can bring to each struggle.” —Aurora Levins Morales, Kindling

Solidarity is not easy. It is ongoing. It requires patience and understanding. It requires grace. Because if we fail and make mistakes, which we all will and do, how do you show me grace when I am not my best self? How do we not reinforce carceral and punitive relationships with each other, especially when conflict arises? It requires a constant decolonization of the mind—a deprogramming of white supremacist values that we have been forced and co-opted into.

It requires boundaries and rest. It requires a praxis of love for others and for yourself. It requires study. It requires constructive critique. It requires you to know who your people are because not all people will show up for you like you show up for them. It requires one-anothering. It requires political communion. It requires a radical imagination, even when this world tries to defer our dreams. It requires us to not allow our dreams of a new world to be deferred or to fester. Instead, solidarity pushes us to keep watering those dreams so they can develop, ripen, and grow into ultimate realities.

—Jaimee A. Swift

Leila Raven on healing and the energy to leave or stay

“As the pandemic has worn on, it has brought grief without closure, caregiving responsibilities without relief, and glaring cracks in the foundations of past solidarities. Three months in, I was still organizing on mutual-aid projects the way I always had, biting my tongue about the gendered, inequitable distribution of resources and labor. Six months in, my own housing conditions were impossible to ignore: a building that shook when buses passed, cracks in the ceiling, an eviction notice under my door. Nine months in, NYC public schools had my six-year-old on a daily schedule of Zoom meetings that rivaled my own schedule.

One year later, I could no longer see the value in public schooling that teaches the history of colonizers rather than my Caribbean ancestors’ history of resistance. I could no longer remain in organizing spaces where survivors are asked to work alongside those who have raped and abused us, where accountability meetings escalate to public calls for accountability that end in smear campaigns against survivors and their allies. I could no longer remain in spaces where organizers, who come to this work because we are directly impacted, are not seen as part of the communities that we’re working to protect.

Now, I direct my energy toward building spaces and deepening relationships that center healing, wellness, and care; where my own culture and history is studied and celebrated; where solidarity looks like taking responsibility for my own ongoing healing and political education work while finding my people and holding them close.”

Leila Raven is a queer, Afro-Latina mama and community organizer building safety without prisons or policing. She is the former director of Collective Action for Safe Spaces (CASS) and a co-creator of 8 to Abolition. She can be found tweeting and Instagramming at @bubblybutfierce.

SX Noir on making room for conflict

“What I’ve really learned is: we have to have room for conflict and room for the discovery of new things, including learning and unlearning. A lot of the violence I’ve seen around organizing and activism is when people lack empathy, patience, and understanding of those who are different from them. We’re trained to understand patriarchal concepts around money, love, and friendship … When we’re confronted with something different, it can be difficult for people to move past that.

We need space for conflict, for people to be upset and angry, and more importantly, for people to move forward and work through these pains. Conflict is not inherently bad. This idea that we are exempt from conflict is just not true. It’s often at the crux of our movement. The people I’ve grown with in this work are people that tend to be resilient and patient. We need to give each other space to not be perfect.

Organizers and activists are not protected and not safe, and this is incredibly dangerous work. Black and Asian communities have so many parallels in the fight for sex workers’ rights, and we have to stand together in solidarity. The way I feel oppressed as a Black woman—I look to my Asian sisters and see the same dynamics happening. I see it in gun violence, I see it in our poverty… and last but not least, the emotional labor of our existence. It’s important to move forward with empathy and love.”

SX Noir hosts the podcast Thot Leader Pod about sex, love, dating, and tech. She works to destigmatize the conversation regarding sex in digital space. Read her conversation with Kate Zen on solidarity and sex worker activism.

The Process of Building Together

“Maybe the purpose of being here, wherever we are, is to increase the durability and occasions of love among and between peoples.” —June Jordan

How can we survive as a civilization and how can this earth survive as a planet if power, capital, aggression, and detachment are our rulers? Being in solidarity with feminists of color in my life and across the globe is an act of love—for myself, my sisters, and my people. We as humans need each other to survive. Loving communion, or solidarity, will only fuel our survival and our path to freedom.

During the pandemic, I have truly come to recognize how much we must lean on and lead with love in everything that we do in this life moving forward. There is so much violence, destruction, and coldness swirling around us on this earth. It is imperative that we come back to our humanity, our care for one another, and our tenderness. I choose to move through the world with compassion and intentionality… Or at least I promise that I’ll do my best.

—Tiffany Diane Tso

K on friendship in organizing

“In understanding the practice of solidarity, I actually look to friendship. My deep and meaningful friendships with my passionate and brilliant friends guide how I want to show up in the world. My friends push me to be a better comrade by giving me the space to observe how they show up in their own organizing spaces, and also through believing in me when I can’t believe in myself. During the pandemic, solidarity has looked like showing up to each other’s virtual events, challenging each other to read and study even when physically far from our co-organizers, raising money for each other’s mutual-aid goals, spending hours together on FaceTime, coworking and laughing together, journaling, and savoring each special hug.

Supporting my friends’ organizing is important to me. I want them to know that their work matters individually but also collectively. In the future, it will be difficult to see where one group ends and the other begins. We will find our work so intrinsically tied to each other that our structures will be built with others in mind. Our analysis might not have the same name, but it will be a shared analysis because it will always be in service to those who come after us.”

K is an organizer and writer currently based in Atlanta, Georgia. You can find them at kagbebiyi.com and on Instagram and Twitter at @sheabutterfemme.

DJ MOR Love and Joy on organizing with our hearts

“I am convinced more than ever, because of the ‘syndemic’ (intertwined health and sociopolitical crises), that loving, being joyful, and deepening relationships with people and the natural world around us are the foundation on which true solidarities are built and practiced. A very important lesson for me has been to start with purpose, invite folks to join, ask for their participation, and be the keeper of the space for the interactions, conversations, and activities, but never be wedded to outcomes. I am committed to the processes of keeping a space open, ongoing, consistent, inviting.

And, ultimately, our work in this political moment is about love and joy. This commitment to love and joy has enabled me to recognize and acknowledge folks for who they are, invite them to come as they are and whenever they are able. I have learned, too, the power of reaching and embracing across geographic boundaries and ages, and to see through and beyond the usual, socially constructed categories of race, class, gender, and so on. It is important to see others with our hearts in order to recognize them more fully.”

DJ MOR Love and Joy (also known as Dr. Margo Okazawa-Rey) creates opportunities to play music and create dance parties wherever and whenever. Read her conversation with Jaimee A. Swift on the radical possibilities of leading with love.

Over a year after the pandemic started, the institutions and systems that have failed us are telling us to “go back.” In the words of Lynn Shon and José Luis Vilson, “No, we’re not going back.”

We need each other. We need each other more than ever.

We can build new worlds together by nourishing each other through crafting “constellations of care” on small, intimate scales. This means taking the time and patience to cultivate consistent relationships where we can be generous, graceful, and kind to each other in the face of conflict and mistakes. That we care for one another and make space for collective grief and pain. That we make room for rest, breaks, and healing. It means unlearning the ways white supremacy embeds itself in our everyday lives and in our friendships and political coalitions. It means refusing the hostile structures. It means crafting political commitments that serve the liberation of our communities not institutions. It means engaging in the ongoing practice of study to build shared radical consciousness.

We see so much possibility in building movements otherwise and doing political work together. It won’t be easy, but we need to come together and continue to imagine and create a new world where we can all truly be free.

Salonee Bhaman, Rachel Kuo, Jaimee A. Swift, and Tiffany Diane Tso are co-editors of the Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities Project, a collaboration between the Asian American Feminist Collective, Black Women Radicals, and the Asian American Writers’ Workshop.