‘We pulled together as much of our body parts as we could. We collected everything we lost in sleep, everything we gained, as a three hour-long silence spread over Kathmandu.’

September 10, 2015

On Sunday, August 30, we invited five writers to the Queens Museum in Flushing Meadows Park to respond to works in the Museum’s exhibition of Indian modernist and contemporary art, After Midnight, which closes this Sunday, September 13.

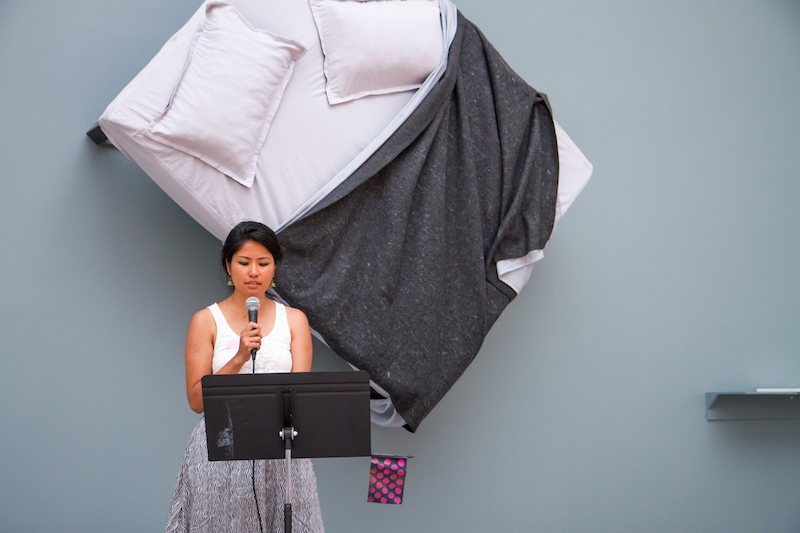

The following piece by Muna Gurung was written in response to Tushar Joag’s “Are You Awake?” 2013. Bed, headphones, books, and wall text.

While We Slept

“Taking a nap is the only way out of this heat,” our Aamas said. “Plus, don’t you know sleeping makes you grow taller?”

So they opened up all the windows, laid Styrofoam mats along the corridor, and instructed us to lie down. “Just for two hours,” they said.

To help us sleep, they told us the same story of Sunkesari nani—the golden haired girl who loved her brothers so much she sacrificed herself to the monster. The monster ate her from her feet. When his mouth reached her chest, she spread her arms wide; he could not swallow further, and he could not throw her up.

But our Aamas always fell asleep before we did. We found out by the way their feet gently fanned outwards, falling to their sides. We watched their breasts slowly slide to meet their armpits. We watched the corners of their mouths slink downwards, as though pulled by rope, like the white man Gulliver from our textbooks, who was tied up by tiny people while he slept.

We lay awake.

Some of us learned how to masturbate, some of us did homework, some of us stole from our mother’s purses—we were careful to oil the hinges of the metallic Godrej cupboard, to silence that familiar sound that signaled money and secrets. Some of us climbed into the back balcony and lit a cigarette, a cigarette we rolled with newspaper and tealeaves. Some of us touched each other—starting with the hair, then the scalp, the earlobe, and finally skin—skin always the temperature of cool fruit.

Later as teenagers, there was nothing our Aamas could do to keep us awake. We learned to lock our doors. We slept in loud music. We slept during class: sometimes we stole a 10-minute bathroom break, sometimes we took turns keeping watch, sometimes we worked our fingers like visors, rested our heads in our palms with sleep hovering over our math equations.

On Saturday mornings, after a bath, we laid out in the sun to dry our hair, oil our hair, and eat oranges, papayas, pomelos depending on the season. Eventually, we fell asleep over, under, and around each other. While we slept, crows swept down to peck on the seeds, the skins, the fibres. While we slept, the concrete of the terrace under our bodies molded to hold us. While we slept, our futures rose and tore themselves away from each other.

We woke up at 2PM to watch the week’s Hindi movie on national TV. We walked down to our living room with the backs of our knees wet from sweat, a shade browner, a little lonely, a little together. We sat in couches with our legs curled up, our palms holding the soles of our feet. After the nap, we pulled together as much of our body parts as we could. We collected everything we lost in sleep, everything we gained, as a three hour-long silence spread over Kathmandu.

Years later, these moments of sleep—when our bodies touched, how and for how long—will become a way we learn to remember each other. Elbows that were dry from resting on surfaces too much—desk, grass, concrete. Knees that were prickly because we forgot to shave right there. Heels so cracked they undid threads from our skirts, blouses. The shapes of the polio shot scars on our arms: a button, a raisin, a large deep-fried potato chip, changing with each nap, each week. Warm skin that grew hair—first one, then three, then a patch, thinning towards the tips, hiding what we have slept to know.

In naps, we spoke and learned of each other’s desires and shame. We woke up a little guilty, a little happy.

We’ve stopped taking naps now. They only leave us to wake up on our own, with fossil marks from the folds of our own skin, our own clothes, our own choices.

Read other pieces in our series from the Queens Museum’s After Midnight exhibition:

Hari Kunzru, “The Degenerates”

in response to F.N. Souza’s “Degenerates”

Swati Khurana, “Indexing a Life”

in response to Dayanita Singh’s “File Room”

Muna Gurung, “While We Slept”

in response to Tushar Joag’s “Are You Awake?”

Chaya Babu, “Good Girls Don’t Say Such Things”

in response to Subodh Gupta’s “What does the room encompass that is not in the city?”

Amitava Kumar, “At the Queens Museum”

in response to Subodh Gupta’s “What does the room encompass that is not in the city?”