Against the hills, a tall building with plank-walled rooms. / I, wishing for my wife and son like clouds far away, / My night is even longer under the bright moon.

June 12, 2018

Carved into the walls of the Angel Island detention center are the poems of Chinese men and women who migrated to the United States during the early 20th century. The first group of immigrants to be targeted by U.S. immigration policy by Chinese-exclusionary laws passed by Congress in the 1880’s, Chinese laborers were forced to undergo intensive interrogations upon arrival in order to prove their authentic relation to American citizens. Located in the San Francisco Bay, Angel Island was the “Ellis Island of the West,” where immigrants were held in detention for days, weeks, and sometimes months before their deciding interview took place.

Newly translated by Jeffrey Thomas Leong in the collection Wild Geese Sorrow, the Chinese wall inscriptions are an important archive of America’s racist anti-immigrant history, and are still resonant with the country today.

Leong will be doing a book talk and reading from Wild Geese Sorrow at City Lore, New York on Thursday, June 28th at 7 p.m. Read the collection’s foreword and selected poems below.

To reach San Francisco from Hong Kong you have traveled nearly seven thousand miles, on a steamer journey of more than three weeks; the conditions on the ship have been brutal and cramped. The year might be 1910 or 1925 or 1938. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, you will only be allowed to enter the United States if you can prove that one of your relatives is lawfully living in what you hope will be your new homeland. And when you at last reach your destination, you find yourself incarcerated in a rude wooden barracks at the Angel Island Immigration Station, with scores of other hopeful Chinese immigrants, most of them like you, men in their early twenties.

You are aware that the American authorities will question you in order to determine that you are indeed who you claim to be. Before leaving, you were told to expect the interrogators’ questions to be pedantic, relentless, and exhausting. Their goal is to trip you up, catch you in a falsehood. Until proven otherwise, you are assumed to be a “paper son,” who has fabricated the identities of your relatives. You have prepared for this onslaught, memorizing every possible detail about your family history, your village and its inhabitants. You have in essence had to create through memorization, a kind of personal Wikipedia or Google Earth.

After days, weeks, or months of detention, your interrogation at last takes place. You sit at a table before two questioners and a stenographer. You were wise to prepare for this moment so studiously. The questions are just as unrelenting as you were told. They are bellicose, dehumanizing, and in places downright surreal.

Here is a portion of the interrogation of a detainee named Yee Bing Quai:

Q. When did your alleged father come to the United States?

A. I do not know. He came before I was born.

Q. Has your alleged father made any trips to China since he came to the U.S.?

A. I have never seen my father—my mother told me he returned to the U.S. in CR 14.

Q. If you have never seen your alleged father, how do you recognize the photograph attached to the affidavit you present, as being that of your alleged father?

A. YEE MON TOY of the JEW THIN NGIN store, Bonham Strand, Hong Kong, gave me the affidavit when I went to Hong Kong on my way to the U.S.; and he told me that that was a picture of my father.

Q. Did you ever see any photograph of your alleged father prior to the time you saw the photograph attached to the affidavit?

A. Yes, there is a bust photograph of my father, dressed in American clothes, enclosed in a frame with a glass front, about 6 x 8 inches, which is hanging on the back wall of the center room of my house in HIN village, HPD, China. That photograph of my father has been hanging there as long as I can remember. My mother told me that it was a picture of my father that he sent to her a long time ago. She did not say when he sent her the picture.

The interrogators’ queries are horrific for many reasons, one of them being their guileless debasement of the functions and purposes of language. At its best, the vocabulary of jurisprudence can be exacting, elegant, and even poetic: Kafka’s storied prose style derives in no small measure from his years of writing legal briefs. At its worst, the lingo of jurisprudence is a blunt-force ideological weapon, using what is ostensibly a desire for precision and truth-telling to give falsehood and injustice a veneer of legal respectability. During the Great Terror of the late 1930s, Stalin’s secret police coerced hundreds of thousands of false confessions from his victims; many of them are jaw-droppingly detailed and sadly ingenious in their fabrications of Crimes Against The State.

We see a similar perverse ingeniousness in the Angel Island interrogators’ methods as they are evidenced in the passage above— the coldly calculated repetitions of “alleged father” are surely the most striking example. Of course, the detainees at Angel Island were probably not thinking of the niceties of linguistics and ideology during their interrogations: they simply wanted to begin new lives in the United States.

And yet it is also clear that, before and after their interrogations, many of the Angel Island detainees were indeed thinking of matters of linguistics and ideology, and of how the making of art can serve to redeem words when their uses have been sullied. The Rumanian- born poet Paul Celan was fluent in several languages. In his Bremen address—perhaps the most acute encapsulation of his aesthetic—Celan explained why he chose to write in German, the language of those who sent his sister and parents to the death camps. His purpose, he said, was the cleanse and re-sanctify of the German tongue, to once again make poetry from a language that the Third Reich had made into an instrument of what he called “death-bringing speech.”

No matter what language one employs, to write poetry is always to indict those who would turn our words into death-bringing speech. The poems written by the Angel Island detainees are an especially noteworthy and poignant example of such an indictment. Over two hundred of them have survived: each one is a blow to the Big Lie and to linguistic degradation.

—David Wojahn

30.

The west wind drifts through my thin gauze shirt.

Against the hills, a tall building with plank-walled rooms.

I, wishing for my wife and son like clouds far away,

My night is even longer under the bright moon.

With wine at the head of the bed, my spirit always drunk,

Under a pillow, no flowered dreams or sweet.

One piece of quiet lives only in the heart.

I lean on others to lessen my bitter cool.

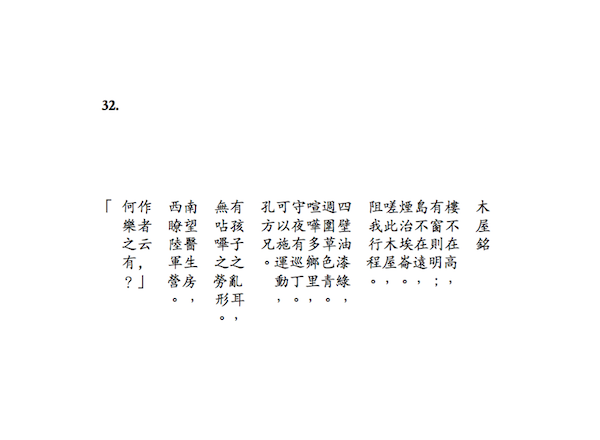

32.

Muhk Nguk Ming (Inscribed Upon the Wood House)

A building need not be tall; with windows, it will have light.

An island need not be far; here, Angel Island.

Alas, a wood building blocks my journey.

Four walls brushed green, contained by grass tinted green.

Inside, a cacophony of village dialects; night silenced

by pale guards.

To make “luck” happen, the square-holed elder brother.

There are children to disturb the ears, but no speech

to muddle over.

Towards the south, I observe the immigration hospital. The west, an army camp.

This author says, “When a prisoner lives there,

what happiness can it have?”

49.

My petition denied already half a year with no further news.

Who knew that today, I would be deported back

to Tang Mountain?

At mid-ship, I’ll suffer waves, and pearl-like tears will fall.

On a clear night, three times I’ll find the bitterness hard to bear.

57.

Angel’s wood house of three rafters merely shelters the body.

Island foothills contain stories impossible to share.

Wait to spin somersaults on my approval day,

Raze the immigration station without speaking of benevolence!

Toishan Man

This excerpt is reprinted from Wild Geese Sorrow: The Chinese Wall Inscriptions at Angel Island translated from the Chinese by Jeffrey Thomas Leong. The anonymous Chinese poems were first discovered on the Angel Island barracks walls and are in the public domain. Translations and text © 2018 Jeffrey Thomas Leong. Copyright © 2018 Calypso Editions. Used with permission of the publisher, Calypso Editions. All rights reserved.