Negotiating a new identity in a new country amid sisterhood and community.

October 12, 2017

Azza Zaki discovered the adult education program at the Arab American Association of New York (AAANY) three years ago when she brought her son for SAT prep classes on a friend’s suggestion, accompanying him each afternoon from 4.00 p.m. to 6.00 p.m. Observing the many women, immigrants like herself, walking in through the doors, Azza became inspired to sign up for English lessons but quickly discovered there was a long waitlist. When a spot opened up, she was placed in Beginner English, Level 2. An earnest student, Azza became president of her class and today she has worked her way up to the Advanced English Level and serves as a volunteer teacher in the Literacy Class.

“When I first started, I found it difficult. I didn’t know anyone; I sat quietly in class,” Azza, who is from Egypt, tells me after the ACS workshop is over. “But AWAL and then the Union of Arab Women have changed me! It’s very helpful to know your rights. If your kid faces problems at school you know how to deal. I’ve taken the self-defense and immigrant rights workshop many times. I go to many, many protests! Most recently, I went to City Hall for the adult education budget. Somia supported us to prepare and make speeches in front of everyone. We are a democracy here!”

“My husband works at a car service but he is actually a civil engineer. And I’m a judge in my country! But here? I’m nothing. No-thing!”

Azza is ebullient with conviction, her whole being lit with the fire of activism and a new-found confidence. I find it difficult to imagine her here in her early days, sitting silently in the back of the room. “Before, I didn’t have any friends,” she confides, “but now AAANY is my second family. Everyone works here together as one hand. This place supports everyone.”

Nasifa El Kholeimy has been a member of AAANY for four years and has earned an advanced diploma in English. Like Azza, Nasifa is from Egypt and a member of the Union of Arab Women. Her daughter attends medical school and her son is in high school, she tells me proudly. “My husband works at a car service but he is actually a civil engineer. And I’m a judge in my country! But here? I’m nothing. No-thing!” she exclaims, splicing the word into emphatic syllables.

“When I come to AAANY, I feel like a strong woman. I volunteer here and help out. I couldn’t speak a word when I first came. I was too scared to go alone anywhere. But now, I go to the doctor, the supermarket, my son’s school, my daughter’s college… I can open any letter and understand it. I can do anything!” she says, brimming with excitement.

Weam landed alone in New York in the depth of winter, relieved to be reunited in safety with her family. Bombs had been exploding daily in Baghdad. Her husband, a structural design engineer, worked for an American company in Iraq which had rendered their lives there all the riskier.

To descend from the lofty position of deciding court cases in Egypt to feeling utterly dependent in undertaking the most mundane of tasks has got to be the epitome of culture shock, I think to myself as I listen to Nasifa. And yet, optimism and enthusiasm drive her conversation. “Union of Arab Women is so supportive,” she says. “It makes strong women! And we are like a family, everybody helping everybody, not just my own friend or neighbor.”

Azza, who’d been listening and nodding as Nasifa spoke, stood now and took her leave. Amal Mohammed sat down eagerly in our small circle. A mother of two, she joined the Union of Arab Women a year ago and that remains the focus of her participation in AAANY. “This is new for me— the women’s group. At home, I was a social worker. Now, I am an immigrant. But also a confident woman!” she smiles.

The call to Dhur prayers, piped through speakers, suddenly fills the large community hall and the few women who’d stayed back in the classroom after the ACS workshop to speak with me now get up. I watch them line up shoulder-to-shoulder in the communal area, facing the direction of the qibla. I have a scarf in my bag and just as I decide to get up to perform the ritual ablution in preparation for prayer, Weam joins me and sits down.

She tells me that she and her family fled war-torn Baghdad three and a half years ago. Her husband and four children arrived in America before her as there was a delay in processing her papers. Weam landed alone in New York in the depth of winter, relieved to be reunited in safety with her family. Bombs had been exploding daily in Baghdad. Her husband, a structural design engineer, worked for an American company in Iraq which had rendered their lives there all the riskier. Weam, a structural engineer by profession, too, is determined to stay relevant in her field and aspires to practice her profession in her new country.

“This country supports us to be something. If I don’t take this chance, I can’t be anything in the future.”

Soon after arriving in New York, while she was doing groceries at Balady Market she caught sight of AAANY’s office across the street. “I put in my mind when I complete my papers, I will come here. One month later, I started English classes at AAANY, and two to three months later, I enrolled in structural analysis classes at Cooper Union,” she says. “After six months, I was moved up to Level 4 in English. The whole time I studied English at AAANY it made me understand my studies at Cooper Union. After Level 4, Somia encouraged me to study English at Brooklyn College. Every morning for three hours, I studied English at Brooklyn College and every evening for three hours at AAANY! After I completed the course, Somia invited me to support her classes as a volunteer teacher. She encouraged me to study further. This time I took English classes at La Guardia and Computer, English and History at Staten Island College. When I completed the course, I was hired by AAANY as a part-time teacher.”

I marvel at Weam’s dauntless drive and commitment to fashion a productive life for herself in her new country. “I want students to be like me and get jobs,” she says. “This country supports us to be something. If I don’t take this chance, I can’t be anything in the future.”

But the journey hasn’t been easy. “I’ve faced many, many challenges,” Weam admits. “In the beginning, I had no contact with community. I was self-conscious and embarrassed speaking to anyone. But the Union of Arab Women is a very, very strong program. I found myself here— thanks to Somia, who encouraged me to be something here. If women catch this chance, they can be anything! If you empower yourself, you support yourself!”

We walk out together towards the lobby. Two of the women are still in prayer completing supererogatory prayers beyond the four cycles of compulsory Dhur.

Weam suddenly says to me, “I love very much the Pakistani people, I know your people. As soon as I saw you, I don’t know why, but I knew you were Pakistani!”

——————

I find Somia and Kawtare in the lobby, seated beneath a framed landscape of the Masjid Al-Haram, the Great Mosque of Mecca, sipping tea from paper cups. A large silver flask sits on the counter.

“How do you think the women responded to their first ACS workshop?” I ask.

“Actually, some of them didn’t know about ACS. Now, it’s good they’ve learned about it,” says Somia. “Today we were focusing on how important it is to make your kids feel comfortable to speak to you about their problems, and to listen calmly, and make them confident and proud of themselves.”

“Were you expecting the answers they gave?”

Kawtare furrows her brow. “They are just like my mom when we have these conversations. When we were in school in France misbehaving, talking back, being violent, that’s because it was a tough life. My parents tried to give us the best they could with the little they had. They managed to raise healthy kids who now have their own homes. But, inside, there’s something very hurt,” she says, clenching her fist.

“I want these mothers to understand that their teenagers live not only in a different country but in another era right now—technology! There’s the daily struggle of being Muslim because of the media. A lot of kids don’t feel comfortable at school, and they don’t feel comfortable at home. We need to reconstruct our homes; we need to talk about identity. We are not just Yemeni anymore, not just Moroccan. We are American Muslims. And we need to take care of that identity—so that it is something that will make us grow strong and build a safe, healthy, equal society.”

——————

The sun is high and heat rises off the pavement as Somia, Weam and I leave the Beit El-Maqdis Islamic Center. I marvel at the size of the mosque and its adjoining community center that impressively occupy the entire block of Sixth Avenue between 62nd and 63rd Streets. Traffic roars above us on the expressway as we make our way back to AAANY’s offices on Fifth Avenue. An empty playing field carpeted with wild grass offers respite from the otherwise drab surroundings. Shabby row houses, some with steel doors, huddle together on either side of the street.

“Alhamdulillah! After Trump I realize we are stronger than before!” exclaims Somia. “Our community is unified. We have joined hands; we hold each other. People come to us and say, we want to help… I want to say, ‘Thank you, Trump! This is the best gift!'”

“After Trump won the election, some people in our community said they felt hopeless, like they’d built something and now it was gone,” Somia says as we tread single file along a narrow patch of sidewalk. “Some who are undocumented were really scared. We encouraged them to speak and share their stories—why did they come to America, what are they looking for, and what do they think is going to happen next. It was really moving to hear the stories. We cried. People lost confidence and hope after election day. What was going to happen to their kids?” Somia’s voice ascends to a high pitch. “This is really our main concern: What are we going to do?”

At the Ford Foundation convening on islamophobia last year, community leaders voiced their concern that Muslim New Yorkers were feeling and experiencing anti-Muslim bigotry at unprecedented levels. They blamed the heightened discrimination on policies that view Muslims through a national security lens. Even as immigrant communities combat hate speech and violence, they simultaneously contend with palpable issues of poverty, educational barriers, and lack of health care. “We are like people putting out fires with buckets. But this approach isn’t working anymore because the fire is so huge. We can’t just be reactionary. We need to build the firehouse,” Linda Sarsour had declared at the gathering.

“Alhamdulillah! After Trump I realize we are stronger than before!” exclaims Somia. “Our community is unified. We have joined hands; we hold each other. People come to us and say, we want to help. We don’t have money to donate but we have time. I want to say, ‘Thank you, Trump! This is the best gift!'”

“You lift everyone up around you! You’re so positive, Somia” I blurt, genuinely taken by her optimism.

“But when I came to the United States ten years ago, I didn’t know where to begin,” she confesses. “I studied English, but then what? I didn’t know how to find a job. I came to AAANY—the magical place, I call it!—as a volunteer and found myself. Why am I going to keep this to myself? I thought. I should help others like me. I know people, new here, who just don’t know where to start. I support them, show them the right way, the right direction. I was in the same basket. I tell them my story. Alhamdulillah! It’s really helped them. I could say that the magical thing is: if you love something, you’re going to succeed no matter the challenges facing you. You’re going to win in the end.”

Somia is overcome by a coughing spasm and we slow down. Regaining her breath, she tells me about a young woman from Virginia who called her two years ago, having heard that she helped immigrant women. “She was broken–hearted. Everything finished, everything ended after four years of marriage.”

On Somia’s suggestion she moved to New York. She was assisted in finding a job in Bay Ridge and a shared apartment with a roommate. She came to AAANY for four months before moving to a new job. “Last week she got married! We had a small party at the Association. I did the last part of my job,” Somia throws her head back and laughs. “The director of our board performed the Islamic ceremony and did the paperwork for her. I thought, yes, we did our job to the very end! This is why our community is so special!”

A prim Caucasian woman with wavy hair, dressed in a 1950s hat and fawn skirt suit approaches us on the footpath. She steps forward, smiles at the three of us and hands out glossy pamphlets, all the while speaking Arabic inflected with an American accent. I glance at the handout—Biblical quotes about paradise printed in Arabic. “Shukrun!” Somia says politely, folding hers and walking on. I follow suit, confused. When we are out of earshot, I ask, “Was that a Christian missionary? Speaking in Arabic?”

“There are lots of them here,” Somia replies matter-of-factly. “Some of them come to the Association. They come to ask us what we believe in, how it’s same or different from their religion. If you want to convert, you convert. But if you truly believe what you believe, nobody can change your mind.

“Our neighborhood is really special!” she adds, laughing.

——————

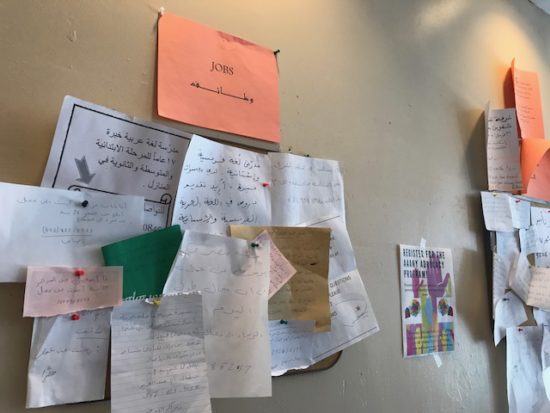

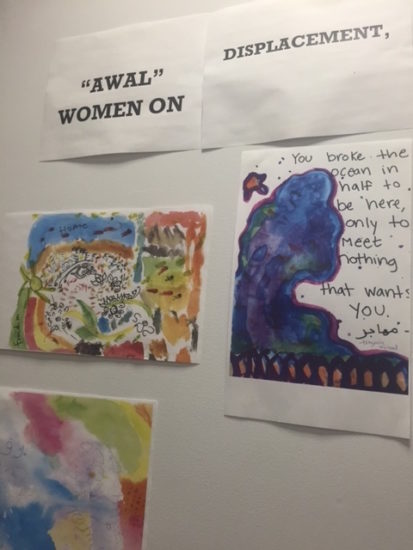

The foyer of AAANY is packed, people waiting for their appointments, tinkering on their cellphones. Somia leads me past walls adorned with images of rallies and protests, a striking vintage photo of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, art work and poetry by AWAL members, and up a flight of stairs to her office that is directly across from the little green room we met in last week. Her colorful desk catches my eye, as does the wall around it, abundantly tacked with photos and memorabilia.

“Enas is the one who grabbed me and brought me to AAANY five years ago! We were studying at Kingsborough Community College at the same time. We do everything together!” Somia says exuberantly, then excuses herself and shuts the door behind her.

Enas is dressed in a bright Jackson Pollock-esque tunic with black pants, pointy black ankle boots and a beige headscarf. “Right now, as immigration outreach officer, I’m busy going out and telling people about Action NYC,” she explains. “A lot of people don’t know it’s a free immigration legal help program, funded by New York City. It’s completely safe. All information is saved privately between the client, lawyer and case worker.”

Enas tells me she accompanies Somia to some of her Know Your Rights workshops at Beit Al Maqdis and sets up a table outside. “The women basically know about 10 percent of what’s going on in terms of immigration and rights. I give a short presentation and let them know they can come to the office for a consultation. Sometimes, they ask me all these questions about their situation, but I’m not a lawyer. I’m just there to direct them to the experts.”

Enas studied English Literature at the University of Sana’a in Yemen, but didn’t graduate. Instead, she came as a visitor to the USA in 2008 while her father was on a diplomatic post here. During her visit, she was married to a man of Yemeni origin. A year later, she found herself alone, a divorced mother of a baby girl. It was in that challenging time that she met Somia. Both were working towards certificates at Kingsborough Community College, and in their spare time dreaming and hatching plans of moving to Germany to further their studies.

“There’s a strong connection between me and Somia,” Enas says. “For me, she’s an idol, I don’t know how she does all the stuff she does! Sometimes, she makes me crazy, like when she decides last moment to hold an event the next day. She’ll do it and a lot of people will attend!”

As if on cue, Somia elbows the door open and comes back carrying a tray laden with Arabic sweets, honey soaked and stuffed with sweet cheese and cream. “There’s a huge box of these downstairs from a client,” she says, breathless from the climb up. She fills a generous plate and sets it before me.

“Were you seriously thinking of going to Germany, Somia?” I ask in mock-horror.

She laughs heartily. “That’s before AAANY changed my life! But, yeah, Enas and I are like twins, we don’t move without each other.”

——————

A week later, I am back at Beit Al Maqdis Islamic Center. It’s a busy morning; four of the eight classrooms are in session. A male teacher in a gray suit paces the floor in one room, dictating sentences aloud that his students appear to be jotting down: “The number of people covered by private insurance in 2015… The number of people covered by government insurance has increased by 30 percent or nine million…” His voice floats above the classroom walls. A female teacher in hijab is leading a class in the adjacent room which is filled to capacity. All the students are women. There is no question of mixed-gender classes.

Two women in niqab, one wearing a gold puffer jacket over her abaya, stand slightly apart watching the others practice the exercise.

“What if a hijab is pulled from the back?”

I walk around, discreetly glancing into the classrooms. Each room opens on to the central communal space. I enter an empty one, captivated by the large Arabic calligraphy designed for children that covers the classroom’s movable walls. Handmade signs dangle from the ceiling, each inscribed with the name of a prophet in Arabic. In the washroom, I discover picture posters with child characters taped on the mirror above the sinks, depicting step-by-step instructions on how to perform wudu, the ritual ablution before prayer.

Separated from the main communal hall, in a large room, members of the Union of Arab Women and students of the advocacy program are enunciating La!—“No” in Arabic—in three different tones, ranging from low and serious to a shrill scream. A pair of instructors from the Center for Anti-violence Education is teaching a self-defense workshop on using voice and physical techniques. I stand back and watch. Of the 30 participants, the bold and extroverted are offering full-throated shouts of I belong here! or No! Stop! I said STOP! while the shy ones self-consciously mutter the phrases sotto voce.

Outfitted in black T-shirts and pants, the instructors model the next exercise—how to respond if someone grabs their hijab. “The goal is to escape, not fight!” The technique involves lifting a knee up and sharply bringing the heel down on the aggressor’s foot, followed by a kick to the shin or knee depending on the severity of the threat. “Do it fast and run!” Next comes a move that involves striking the nose—to be used in extremely dangerous situations. Participants pair up, taking turns to swing their arms back, mimicking a backstroke. “As women, we are strong here,” the instructor says, patting her hips. “We want to use that!”

Two women in niqab, one wearing a gold puffer jacket over her abaya, stand slightly apart watching the others practice the exercise.

“What if a hijab is pulled from the back?”

The room murmurs. A woman pulls off her flowery headscarf and tosses it to one of the instructors, while another helps her to wrap it to the accompaniment of claps and exclamations of “Nice! Nice!” The instructors then roleplay a scenario of a potential assault from behind and demonstrate the self-defense moves.

Gone is the staid demeanor of mothers and grandmothers. Giggling and shouting their self-defense lines, swinging their arms and practicing leg moves, the women have transformed the room into a veritable playground!

Read Part 1: These Streets are Ours Too

Read Part 2: Your Kids Need Hub! They Need Love

Read Part 4: A Spirited Sisterhood