In a new collection from A World Without Cages, seven writers reflect on building a different future while holding the weight of the past

February 21, 2020

In 1962, just before the Emancipation Proclamation turned a century old, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his nephew. “You know, and I know, that the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon,” he wrote.

His letter also spoke about building a different kind of world. “We can make America what America must become,” he wrote. “We, with love, shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.”

At the end of the letter, Baldwin quoted a spiritual: The very time I thought I was lost, My dungeon shook and my chains shook off.

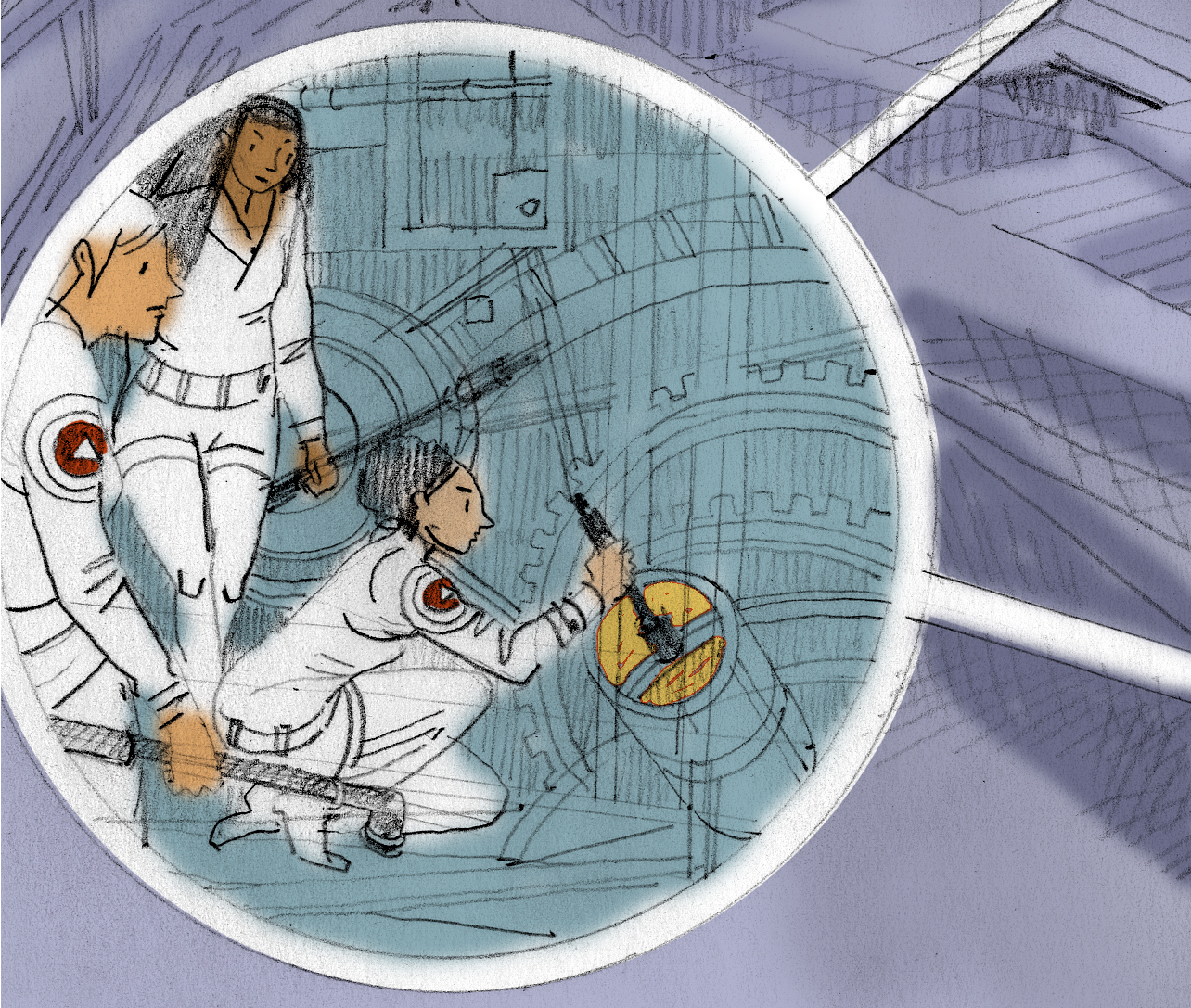

Recently, CM Campbell created a comic with Adam Roberts, who has been incarcerated for two decades, and they named it after the same spiritual. “Their Dungeon Shook” is the story of two men, Cody and Ray, who play Dungeons & Dragons inside Auburn Correctional Facility. The game is a way to flee, for a little while, the reality of their incarceration.

It is a kind of world-building, too. As long as Cody and Ray play Dungeons & Dragons, they inhabit a world of their own making. An edition of the Dungeon Master’s Guide describes it this way: “Not only do you get to tell fantastic stories about heroes, villains, monsters, and magic, but you also get to create the world in which these stories live.”

The third portfolio from A World Without Cages, a collection of incarceration literature from AAWW, traces the theme of world-building through works by seven writers. In the essay “For Future People,” Roshan Abraham imagines incarceration as a kind of towering, time-stealing machine: tens of millions of years are trapped inside, waiting to be released. “In one of those endless, labyrinthine rooms,” he writes, “is a gear we can jam to crash these towers, to take us all home together, to whatever new worlds we’ve built for each other.”

Some of these works build, for the reader, the world of incarceration itself. “Tonight, surrounded by the walls of a prison, / there is a traveller who is hugging his sorrow,” writes Chu Ngoc Tu Nguyen in the poem “Withering Life,” translated from Vietnamese by Phạm Thu Uyên. Chu has been incarcerated in Michigan since 1999.

Many years wandering the underworld

bringing misfortune to other beings

only to fall into the hands of law

one winter night, wrists in handcuffs.

All fantasies shattered:

Family, friends, dear lover,

freedom is far away.

In the essay “My Name is Chino,” Hoàng Vu Tran tries to describe a sentence of 60 years—a span of time he cannot fully fathom, that contains many lifetimes. When he becomes eligible for release after 30 years of incarceration in the Texas prison system, he expects to be deported to Vietnam. “I am terrified to think that my family escaped Vietnam only for me to return there almost 50 years later, in handcuffs,” he writes. “To be honest, anywhere is better than to live without hope and the feel of sunshine on my face.”

The poet Connie Leung, who has published two poems on The Margins, will also become eligible for release after three decades in prison. In a letter, she asked the writer Sarah Wang to reconstruct a world she once knew: her old neighborhood of East Harlem. “I will be happy to be your eyes,” Wang wrote back.

I can tell you that there are a lot of taco stands, taco trucks, fresh fruit juice vendors on the street, and a lady who sells yogurt out of a red plastic cooler on the corner. There is a soccer shop across the street that sells memorabilia, uniforms, and of course soccer balls. There is a cuchifritos place, a bakery downstairs that wafts smells of butter and yeast up into my apartment in the early hours of dawn, a beauty supply with a good selection of wigs down the block…

Three of these pieces—“Their Dungeon Shook,” “For Future People,” and “We Are Still Here”—emerged from the AAWW Witness Program, a fellowship that took four writers of color to sites of incarceration, and that introduced them to incarcerated writers by mail.

As part of their correspondence, Leung and Wang traded letters about many things, from books and jobs to family and trauma. Often, they wrote about the thing that makes world-building possible: language, “a thing with infinite power and strength.”

The five works in this portfolio imagine a future that our words can create. They invite us to listen, and they urge us to speak. “I encourage you to trust your voice,” Leung wrote from prison. “It’s not about how well received it may or may not be. It’s about claiming that we do have a voice… and that no matter how hard people tried to stomp it out of us, we are still ‘here.’”