Cathy Linh Che talks about her debut collection of poems, Split, and what it means to mimic flashbacks of war, immigration, and sexual violence.

October 16, 2014

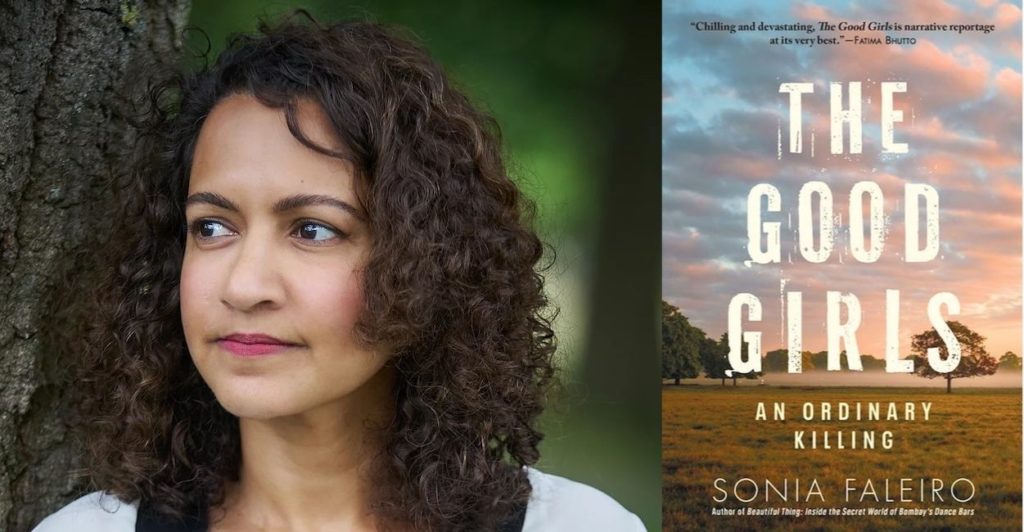

Cathy Linh Che’s debut collection of poetry, Split, arose out of poems she wrote of her parents’ stories of the Vietnam War and the lives they made in the United States following their escape after the fall of Saigon. Connecting those recollections to her own experiences as a survivor of childhood sexual assault, the poems in Split touch upon the enduring trauma of violence. Publisher’s Weekly writes of Cathy’s book: “To be a daughter, a survivor, and a poet are all aligned in the need ‘to rewrite everything,’ a need that Che navigates with brutality and tenderness, devastation and irrepressible endurance.” Bushra Rehman, author of Corona, interviewed Cathy about the collection, and among other things they talk about mimicking the effect of triggers, flashbacks, and memories in Split.

Read “Letters to Doc,” a poem from Cathy Linh Che’s Split published earlier this year in The Margins.

Bushra Rehman: Cathy, I read your book, Split, on a subway ride home. And I realized I had become one of those people on the train who talks to herself, because I was murmuring “wow” at a turn of phrase, an image perfectly rendered. Thanks for this chance to talk to you.

Cathy Linh Che: Thanks so much, Bushra! First of all, congrats on the success of your book Corona and your recent appearance on NPR’s All Things Considered. How incredibly exciting for you, and for all writers of color—that a national media outlet is discussing race and publishing.

Secondly, your reaction to Split means a great deal to me. I love hearing it because I am not quite sure how a work like mine is received in the world. Sometimes, I think, who wants to hear about my own personal traumas, much less read about them on a subway ride home? But I know that my experiences and my family’s experiences are not singular. Other people share narratives of sexual abuse, war, exile, and immigration, too.

I believe sharing these experiences is transformative, but even beyond this, you have created a deeply moving work of art that is more than a simple confession. From the first page, I felt myself falling down the rabbit hole. It was dark, dangerous, and dreamy in an engrossing way that got me to the very end from what felt like moments after starting the book. Perhaps because I read the entire book in one sitting—and have continued to do so almost every time I reread it—I was really affected by the way scenes would almost occur like flashbacks for the reader, reappearing in a later section. We were now having memories, too. Could you talk about this, the way literature can reflect the patterns of the mind?

I love your description of falling down the rabbit hole. This reflects my conception of recurring trauma. It feels patterned and cyclical and does not end with the original event; rather the feeling of falling into a hole happens again and again throughout one’s life. The word “triggering” is often used today to discuss individuals who live with PTSD, and it does seem to me that this is often how memory works: Flashbacks are triggered by some kind of stimulus, and the memories are relived or remembered vividly, again and again.

I’m very interested in thinking of how a book/collection of poems can work together to create the effect of triggering and recurrence. Some people see their books as collections of individual, stand-alone poem—something I love and deeply admire because each poem has its own legs and heartbeat. But I don’t think that was my goal for Split. I saw poems as being in conversation with one another, and each poem’s fragmentary nature reflected how I conceived of these experiences. They weren’t whole and separate, but rather were experiences which echo forward and back continuously.

In a previous interview, you mentioned that as part of your process you read Martha Collins’ Blue Front, the edited anthology Transforming a Rape Culture, Freud, Maslow and Foucault. In Split, you drop in wonderful nuggets of knowledge, such as traume meaning dream. Could you share a few nuggets that didn’t make it into the book, or that you’re thinking about for future pieces?

In Vietnamese the word for water, nước, is also the same word for country. I am thinking about the fluidity of “country” for people who are refugees, like my parents are, and for the children of refugees, like me. I was born in Los Angeles and have lived my entire life in the United States. While I was raised by Vietnamese parents, ate Vietnamese food, spoke only Vietnamese to my parents, I’ve only visited Vietnam twice: once in my early twenties to visit my grandmother before her death, and once again in my early thirties. During that second trip, I could not stop crying when it was time to leave—I felt such a profound sense of loss at having to leave a place that felt so intuitively and primally like home.

Sarah Gambito, poet and co-founder of Kundiman, recently traveled to the Philippines, where her parents were born and raised. Traveling there made her feel a deep sense of loss too, and destabilized her idea of home. She concluded that she belonged to many homes and many countries. And that idea felt revelatory to me.

You told the stories of your parents’ lives during the Vietnam War, their escape, and their subsequent experience as refugees in the United States before you wrote stories about childhood sexual abuse. I have seen this arc in many artists whose work I love. Could you speak about the artistic growth and personal journey that took you from one subject to the other?

I find that I write into silence. My parents have been telling me their stories of Vietnam throughout my life, and it seemed to me that in movies, newspapers, literature, their voices and stories were egregiously absent. I wanted to address this absence by writing their stories—and really, my story, our Vietnamese and American and Vietnamese American story—so that they could participate in the polyphony of voices constructing the American narrative.

The next silence I felt I had to address was that of being sexually violated as a child and as an adult, by seven different boys and men. I think my parents’ stories were more on the surface. They were big and cultural and obvious and needed to be told. And my stories were in the dark, private, intimate, and frightening.

Both narratives are interesting because they occurred, in some ways, simultaneously. All of these stories happened in our household and overlapped in important ways. I am very interested also in intergenerational trauma, what is passed down from one generation to the next, and how the act of telling can help to address the damage and promote a sense of integration.

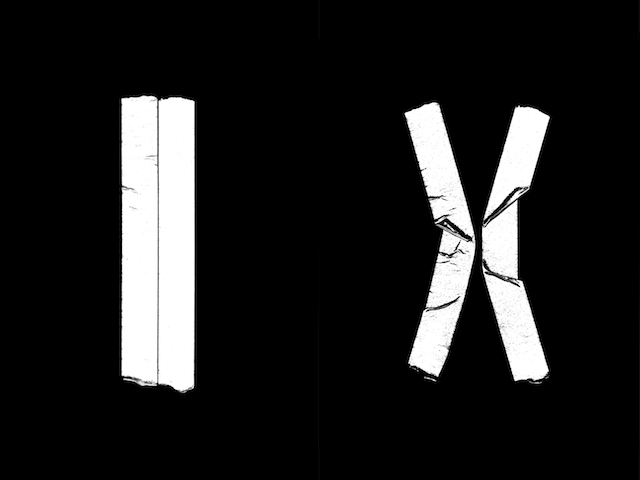

On the cover of Split, we see two strips of masking tape, a familiar item that is suddenly rendered odd or strange by artist Sydney S. Kim. Could you tell me what drew you to this cover and this artist’s work and how it became the image for your book?

Sydney S. Kim’s image is from a series called “Girlfriend Tape,” which renders twenty-three pairs of masking tape in a variety positions, and there is a photocopied effect to them as well. The images feel abstract, but also representational. I like their grit and their intimacy and their suggestiveness. I love that they symbolize chromosome pairs, which to me calls to mind inheritance.

My cover shows two pieces of tape bent to the left toward each other, but never touching. They look like two people spooning or two faces in profile, or soaked band-aids, or flattened cigarettes, or pant legs torn apart, or an undone zipper. To me, they represent lineage, sexuality, damage, and closeness. I love that a simple household item found in most kitchen drawers can speak so multiply and universally. The pieces of tape also work like Rorschach test images. How one reads them reveals one’s inner workings. For instance, does one read damage or healing? Rift or adhesion? Or, does the image look like all these things simultaneously?

Do you want to share anything with someone who reads your book who has also experienced childhood sexual abuse?

Yes. I want to say that it’s important to know that you are not alone. We are not alone. And that, for me, speaking out about my experiences has helped me become a more integrated person. I could not erase what was done to me, but I could write it and share it, and in doing so, own it for myself.