The transnational writer dishes about Law and Order, her favorite drinks, and less-than-romantic writing habits.

June 27, 2012

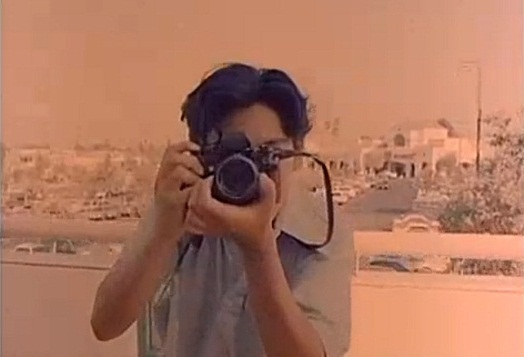

Xu Xi lives in the flight path connecting New York, Hong Kong, and the South Island of New Zealand. The New York Times once named her a “pioneer writer from Asia in English.” She has won an O. Henry Prize Story award and has been shortlisted for the inaugural MAN Asian Literary Award. In 2009, she was the Bedell Distinguished Visiting Writer at the University of Iowa’s nonfiction program. She recently read at AAWW’s event, The Misadventures of Anti-Heroes.

Do you have any guilty pleasures?

Oh yeah—Law and Order! I like junky TV, I like to watch The Clothes… I learned how to plot when I was young by reading mystery novels. I don’t read them any more. I can’t. I try to but I don’t enjoy them anymore. But I learned how to plot from those. I think what substitutes that now is sort of all these crime dramas because they’re very predictable and there’s usually a formula to it. But you have to understand how to make character arise from that. You have to understand within that framework how to tell the story, how to make the narrative turns and all that.

That, and I suppose the Martinis, the Martini and the Scotch. I’m an old barfly, so—

What’s your favorite drink?

Used to be Scotch. I’ve been drinking more vodka lately. But, uh, I love wines. I drink all kinds of wines. But I’m a bit of a purist. I don’t tend to like these sort of concocted, you know, Sex on the Beach kinds of things, these blue drinks with the pink cherry on the top. I’m not really big on that.

But are you on a brand list?

I drink quite a range of vodkas. I can’t say I drink any one only. I like 42 Below at the moment. I discovered it in New Zealand and it’s still cheap here, so that’s another good reason.

Do you usually write at a certain time of day or always at a computer? What’s your typical process like?

Well, if you had asked me that about fifty years ago, [I would have said], “Oh, I love to write first thing in the morning, early, just before the sun rises when it’s so quiet.” You know, it’s terribly romanticized. But the truth of the matter is, if you work full time—which a lot of writers do—if you have to have a job and you have to make a living, you have to carve out a space to write. I taught myself to write at any hour of the day. And that was tough, because I hate writing in the afternoon. But I will do it if I have to, especially if I have a deadline.

I think it’s important for writers not to overly romanticize the idea of the writer—it is an artistic pursuit, yes—but that you don’t spend too much time self-consciously being an artist. It’s a lot about just getting the work done. It’s not that romantic notion or sitting in a garret in Paris, although I have done all these things.

You’ve used four different names that are not pseudonyms and not pen-names but actually your name. You’re Fujianese, also Indonesian, and you’ve lived in New Zealand. I was wondering if you could talk about your identity as a writer, whether it’s tied to a place, and what happens to it when it’s transnationalized?

[When I was young] it didn’t occur to me to write in Chinese because my literary and cultural education was more Western. So I wrote in English. It wasn’t until I was older that it suddenly occurred to me that, you know, this is weird. Why am I—who claims to be an Indonesian citizen, who does not even speak Indonesian, who has a Chinese surname that is transliterated Fujianese, but doesn’t speak a word of Fujianese, who speaks Cantonese as my primary Chinese language, whose father carries on in Mandarin because he can’t stand speaking Cantonese, you know—and then we are all learning English so we presume that English is the language we should use.

After my first book, I was using my American name at the time, which is Shuko. It was a made-up name between my ex-husband and myself to try to combine names and not hyphenate, because we both had long names. It sounded Indian. And of course my first book was totally Chinese and Hong Kong. And everybody want[ed] to know, “Why is this Indian person writing about these Chinese families?”

It never occurred to me that this should be an issue. In America, I published under this name—it was just kind of a name. In Hong Kong though, it was kind of like, “Who the heck is she?” And suddenly the authenticity of who I was came into question. So my American publisher at that time, who spoke fluent Mandarin, said “Why don’t you use your Chinese name?” And I loved my pin-yin name so I used that.