Mythologies have their way of explaining the basic human condition: that there will always be some where or thing you wish to get to or back to.

July 10, 2018

Dao Strom’s latest experimental poetry book, You Will Always Be Someone from Somewhere Else, is both “a collection and a re-collection.” Fragments of family memories, the muddy history of the war, archival photographs, and ruminations on the nation-state are coupled together in English and Vietnamese, translated by Ly Thuy Nguyen. “Mythologies have their way of explaining the basic human condition: that there will always be some where or thing you wish to get to or back to,” writes Strom in this excerpt, which winds through myth, history, and the self to get to that very “some where.”

+

You will always be someone from somewhere else

This is a design flaw of water

+

Mình sẽ luôn là người nọ đến từ nơi nọ.

Đấy là lỗi dòng lội nước.

+ –

Sometimes parents will give their children mythologies when they can no longer stomach history. From my mother I learned the prototypical origin myth, that one about the hand lifting earth to mouth and the inconceivability of the mountain to hold the water that inevitably leaves her for the sea. Mythologies have their way of explaining the basic human condition: that there will always be some where or thing you wish to get to or back to. Which is another way of saying they explain: wars.

Longing is a state of mind.

Which is also to say longing is a mental love.

+ –

Đôi lúc cha mẹ sẽ kể trẻ nghe chuyện thần thoại khi lịch sử không còn giữ được yên trong dạ. Từ mẹ tôi đã học về thần thoại nguyên bản, thần thoại kể về bàn tay nhặt đất lên mồm và sự vô tưởng của núi non không ôm được dòng nước đã để lại nàng cho biển. Thần thoại có cách riêng giải thích cho những điều kiện sơ khởi của loài người: rằng sẽ luôn có một nơi nào đó hay điều gì đó mình ước được đến hay về. Cũng là một cách nói khác về việc thần thoại lý giải chiến tranh.

Trông mong là một thức trạng.

Cũng là để nói rằng trong mong là tình yêu tâm thức.

((the sea))

((the sea))

((biển cả))

((biển cả))

+

But then the water comes back:

Nhưng nước nào rồi cũng ngược dòng:

mang dạng hình nước mắt in the form of tears

((rain)).

((mưa)).

+ –

This is the wound

Đây là vết rách

từ đó ta rời khỏi.

we came out of.

+ –

I grew up listening to my parents fight. It should not have been a surprise, given the wars of their own childhoods, Europe and Vietnam, respectively. But that is not the kind of thing one comprehends as a child, either about one’s parents or about wars. I would lay in bed in the dark listening to them threaten to leave and never return and I thought this was how you loved. But then some mornings I awoke and it was just the crisis in the Middle East they were arguing about.

+ –

Tôi lớn lên nghe ba mẹ cãi nhau. Cũng chẳng có gì đáng ngạc nhiên, nếu biết những cuộc chiến tranh của trẻ thơ tuổi họ, châu Âu và Việt Nam, mỗi người một nỗi. Nhưng đấy không phải điều trẻ con hiểu được, cả về ba mẹ nó lẫn về cách làm ba mẹ. Tôi luôn nằm trên giường trong bóng tối lắng nghe hai người dọa sẽ bỏ đi và không bao giờ trở lại và tôi cứ nghĩ đấy là cách người ta yêu nhau. Nhưng rồi một sáng nọ tôi thức giấc và thực ra họ chỉ đang tranh luận về vùng Trung Á.

+ –

The root of the word “country” takes us back to contra (“against”) and to a phrase where the concept of “country” is arrived at via an act of seeing the terrain spread out before one: terra contrata: the body must separate itself from what it views, in order to name said vision. Hence, the act of first citing or sighting land also becomes one’s initiation of separation. I am against the land. I am against the country. Our perpendicularity to what is beneath, our right-angle-ness, predicates each act of claim and/or divide. In 1960-something, my mother cut her hair short and refused to hand out invitations to her sister’s wedding engagement. When you get up off your knees you disrupt the flow of the lore of the tribe. You disrupt the natural architecture of the horizon, and the sentence. Now you had better learn to swim, or sing.

+ –

Rễ của từ “đất nước” bắt nguồn từ contra (“phản”) và cách nó nối liền sự hình thành của “đất nước” nằm ở việc nhìn nhận địa hình địa vật lan tỏa trước mắt: tera contrata: thân thể phải tách rời khỏi thứ nó nhìn để mà đặt tên điều viễn kiến. Bởi thế, sự ngắm nghía đầu đời một vùng đất cũng chính là bài học vỡ lòng của chia ly. Tôi phản lại đất. Tôi phản lại nước. Sự trực giao của ta đối với những gì bên dưới, góc-độ-chính-xác của ta, là vị ngữ của từng chủ từ khai nhận và/ hay phân tách. Một năm 60 nọ, mẹ tôi cắt tóc ngắn và khước từ việc đưa thiệp mời đám cưới của bác gái. Khi mình nhỏm gối đứng dậy mình đập tan dòng lội khởi thủy của tổ tông. Mình đập tan tầng kiến trúc tự nhiên, và cả câu từ. Thế thì mình nên tập bơi, hay tập hát.

+ –

She was trying to make up her mind and she couldn’t, so she took herself to a movie. Culture beckons. Bombs fall. The tanks were approaching the city and a spring black was descending. She would never see Rome in person, she thought, would never lay eyes on the aspirational architecture of any of those self-congratulating civilizations, if she stayed. My father meanwhile felt sick at even just the thought of the word. Leave.

+ –

Nàng đang cố quyết nhưng không thể, nên nàng bỏ đi xem phim. Văn hóa vẫy gọi. Bom rơi. Bọn xe tăng đang tiến gần thành phố và một máy bay đang hạ cánh. Nàng sẽ chẳng bao giờ tận mắt thấy thành Rome, nàng tự nhủ, sẽ không bao giờ lia mắt qua những kiến trúc đầy khát vọng của những nền văn minh tự huyễn nọ, nếu nàng ở lại. Trong khi đó ba tôi thì chỉ mới nghĩ đến cái từ đó thôi đã phát bệnh. Ra đi.

+

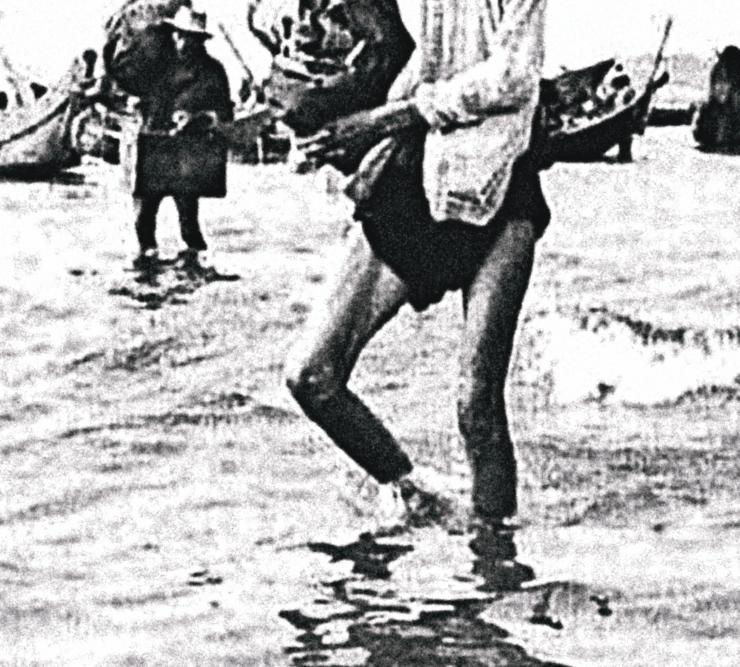

I returned for the first time in 1996. On the beach in Lăng Cô, I sat one evening

with a boy who sold postcards.

—The lost people of Japan, they come a lot too. The lost people like to buy postcards.

—Lost people? What do you mean?

—You are lost people of Vietnam. They all go long time ago and today come back.

—Tourists, you mean. Travelers.

—Tourist? What is tourist?

—The lost people. The people who like to buy postcards.

+

Tôi trở lại lần đầu năm 1996. Ở bãi biển Lăng Cô, một chiều tà nọ tôi ngồi với

một cậu bé bán bưu thiếp.

—Mấy người đi lạc của Nhật, họ cũng hay đến đây. Người đi lạc rất thích mua bưu thiếp.

—Người đi lạc? Ý em là sao?

—Chị là người đi lạc của Việt Nam. Mấy người rời đi hồi xa lắc và hồi này trở lại.

—Ý em là khách du lịch. Du khách ấy.

—Du khách? Du khách là gì?

—Người đi lạc. Những người thích mua bưu thiếp.

+

Separation myth is a middle-class prestige we pull. My own marriage has more than once been beset upon by it. One year I thought a cure might be enacted by returning together to the place I’d previously traveled to alone, which was also the originating place I had been severed from. I wore wings for this trip. We traveled along hectic, inhospitable roads to the oldest standing stones we could make our way to. The ruins of the Champa civilization were called “discovered” in the late 1800s, by French archaeologists who were enthralled at having found such cultural treasures. The Vietnamese, who presumably already knew of those stone feats in the jungle, may’ve thought it just as well to let the jungle keep them. For you have to let the jungle have something: or she will take back everything eventually. But white men come, and often they are intent on saving or vanquishing when they do. On our marriage-saving trip, I hauled my wings in a blue plastic case from north to south. Everywhere we went, the items we bought, entry fees we paid, cost double or triple the local fare, exacted from us with distrustful, scrutinizing eyes. Some charges were blatantly duplicitous. At moments anger would mount in me. I am from here too, I wanted to shout, and I’ve spent a lifetime caring, and carrying, what you think I’ve forgotten, what you think making us pay more for now will somehow vindicate. At the same time I understood well enough where the urge for retribution came from, the years and dynamics implicit. Wool-sick nature of my own tongue; white partner beside me. At the Dalat airport the security officer sent me back to the airline desk to pay more tacked-on fees and at Tan Son Nhut we had to buy our airtickets to Cambodia twice. These small harassments felt like tolls being exacted for something I could not quite put my finger on. Then I set my wings down in the Siem Reap airport. And they were gone when I turned back for them.

+

Bí ẩn về chia ly là thứ trò thượng hạng mà tầng lớp trung lưu chúng ta chơi. Chính hôn sự của bản thân tôi cũng đã từng bị nó bao vây. Một năm nọ tôi đã nghĩ có thể chữa lành bằng cách cùng nhau quay trở lại nơi tôi từng đến một mình, cũng chính là cái nơi khởi tổ mà tôi đã bị tước khỏi. Tôi đeo cánh cho chuyến đi này. Chúng tôi du hành dọc những con đường hớt hải, không mến khách đến những hòn đá cổ xưa nhất chúng tôi có thể đặt chân. Những di tích của nền văn minh Chămpa được “phát hiện” cuối thế kỉ 19, bởi những nhà khảo cổ Pháp mê muội trước ý tưởng tìm thấy những cổ vật văn hóa như vậy. Người Việt Nam, hẳn vốn luôn biết về những tảng đá trong rừng, chắc đã nghĩ thôi cứ để rừng già giữ chúng. Bởi vì chúng ta phải để cho rừng già giữ một thứ gì: nếu không rồi nàng sẽ lấy lại toàn bộ. Nhưng đàn ông da trắng đến, và khi họ đến họ thường có ý cứu giúp hay chiếm ngự. Trong chuyến đi hòng cứu vớt hôn nhân của tôi, tôi kéo đôi cánh của mình đi trong một cái hộp nhựa màu xanh từ bắc tới nam. Mọi nơi chúng tôi đi, những thứ đồ chúng tôi mua, những phí ra vào chúng tôi trả, đều đắt gấp đôi hay gấp ba giá địa phương, đòi hỏi từ chúng tôi với những đôi mắt nghi ngờ buộc tội. Có những món tiền hiển nhiên quá đáng. Có những lúc lòng tôi đầy tức giận. Tôi cũng đến từ nơi đây mà, tôi muốn hét lên, và tôi đã sống cả đời mong ngóng, và mang theo, những gì các người nghĩ rằng tôi đã quên, những gì các người nghĩ rằng bắt chúng tôi trả nhiều tiền hơn thì mới chứng minh được rằng chúng tôi thực nhớ. Cùng lúc đó tôi cũng hiểu rõ nguồn cơn của sự đền bù này, những tháng năm và sự phân cách tiềm ẩn. Cặn chữ lắng trên lưỡi; cạnh tôi là bạn đời da trắng. Ở sân bay Đà Lạt người bảo vệ bắt tôi quay lại bàn sân bay để trả thêm lộ phí và ở Tân Sơn Nhứt chúng tôi phải mua vé máy bay đến Campuchia hai lần. Những sự quấy rối nho nhỏ này giống như đánh thuế một cái gì đó mà tôi không thể chạm tay vào. Rồi ở Siêm Riệp tôi để đôi cánh xuống. Lúc tôi ngoảnh lại nhìn chúng đã biến mất.

+ –

My mother favored the adage by Thomas Wolfe: “You can never go home.” There are pilgrims praying to Buddhist altars under the Hindu friezes, and the temple roofs and doorways are shaped like labia. I read somewhere that Neil Young wrote his song about Cortez the killer after a high school history lesson. The guitar solo too is a snake. Jagging and asymmetric, hissing at ground-level through the song, it is the white man’s best way of evincing that he is both wild and sorry. It comes dancing across the water. Anti-instinct and ancestral. The snake-charmer with his fingertips executes the map. In the ruins: I want to take off my clothes. Every person is deficient in at least one of the four directions.

+ –

Mẹ tôi yêu thích vô cùng câu nói của Thomas Wolfe: “Ngươi sẽ không thể về nhà.” Có những người hành hương cầu dưới bàn thờ Phật ở đền chùa Hindu, những mái chùa và cửa bên mang hình dạng môi ngoài âm vật. Tôi đọc đâu đó Neil Young viết ca khúc về kẻ sát nhân Cortez sau một bài học lịch sử trung học. Đoạn độc tấu guitar cũng là một con rắn. Lởm chởm và bất đối xứng, rít lên ở hạ tầng xuyên suốt bài hát, đấy là cách tốt nhất để đàn ông da trắng chứng tỏ rằng hắn hoang dại và hối tiếc. Nó tới nhảy múa qua làn nước. Chống bản năng và tính tổ. Người thôi miên rắn với những đầu ngón tay thi hành bản đồ. Trong khu di tích: tôi muốn cởi hết áo quần. Ai cũng kém cỏi ít nhất một trong bốn hướng.

This excerpt is reprinted from You Will Always Be Someone From Somewhere Else by Dao Strom. Vietnamese translation by Ly Thuy Nguyen. Used with permission of the publisher, Ajar Press. All rights reserved.