Arab mothers and grandmothers in Bay Ridge discover that in a new country, there are new ways to care for their families, their community, and themselves

September 14, 2017

In the foyer of the Arab American Association of New York (AAANY), someone waiting for their appointment is playing a Quranic recitation on speaker phone as if it is the most natural thing in the world – a public service attunement to the Divine! No one seems to mind. The melodic recitation fills the waiting room which is adorned with a colorful mural made by summer camp youth participants and a billboard crammed with job announcements, all in Arabic. I push open the glass door, taking note of its jagged scar of a crack — the weather? an accident? an act of hate? — and step onto sunlit Fifth Avenue.

I saunter across the street, drawn by the haphazard window display of Balady Halal Foods. To one side, adjacent to a large carton of Mexican mangoes, leans an ornate framed metal work of Arabic calligraphy inscribed with “Allah” and “Mohammed”—the mundane and the sacred abutting each other. The Quranic recitation from the foyer seems to have followed me out on to the street. I can actually make out the words now—…and the sun and the trees both alike, bow in adoration…— Surah Rahman, Surah 55 of the Holy Quran. Marveling and turning towards the source of the sound, I discover speakers at the entrance of the store.

“If I were a new immigrant, surely I’d find a moment of solace here, inhaling the aromas, gazing at and listening to snatches of home.”

Stepping inside, I enter an alternate reality whose defining characteristic is vibrant color. The freshness of green almonds and scarlet pomegranates greet me, along with aloe vera fronds with serrated edges, and fat Medjool dates—I am moved by the synchronicity of the Surah that glorifies creation wafting on to the sidewalk even as I witness this luscious display. It is the Islamic month of Rajab. If in Manhattan that lunar month pregnant with holy symbolism remains hidden as a whisper beneath the scrimmage of daily life, here in Bay Ridge, there are constant reminders!

Gorgeous inlaid wooden chess boxes hover on a shelf above the produce along with hand drums and wicker baskets. Rubber gloves in an assortment of sizes and hues vie for attention next to green and purple cloth bags stamped with the words “My Masjid.” A veritable banquet of nostalgic experience: dates stuffed with almond and smothered in Belgian chocolate, a surfeit of olives, the mingling fragrances of food and the oudh perfume emanating from the garments of passersby, and the constant greetings of peace as shoppers and saleswomen exchange Salam ‘alaykum and Wa ‘alaykum Assalam.

If I were a new immigrant, surely I’d find a moment of solace here, inhaling the aromas, gazing at and listening to snatches of home. Awash with sentiment, I muse: I am an exile of times that will never return, years spent in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Emirates gone forever, but enclosed in me, unfurling now as nostalgia courses through and the desert lands are brought close in this pocket of New York City. I buy two pounds of coffee beans over which the saleslady piles a generous scoop of cardamom pods in the grinder.

Ah, New York! Packed with so many facets of ‘home’ and identity, at once a comfort and an irritation with its mishmash of colliding and coalescing cultures. I stand by the open tray of dates and savor the quintessence of this uniquely American moment.

——————

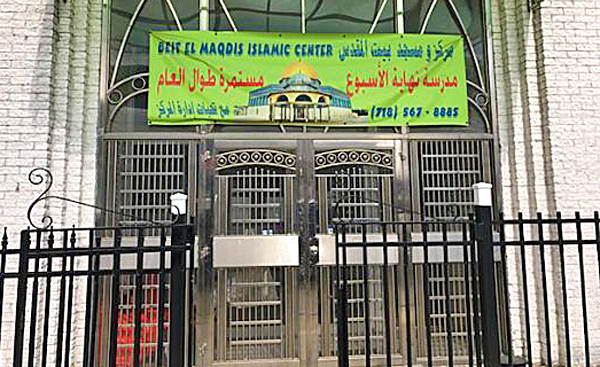

“Your kids need hub—love!” announces Kawtare, an intern at AAANY, (who prefers to be known by just her first name) to a room of 15 women at the Beit El-Maqdis Islamic Center of Bay Ridge. “By showing love, you make your kids feel beautiful, not fearful.”

A “Know Your Rights” workshop, a component of AAANY’s advocacy program, is in progress on this warm, sunny day in April, which also happens to be Passover, thus accounting for the modest turnout. Many of the mothers are home with children as schools are closed, though several women drift in after the presentation has begun, and eventually every chair in the room is occupied.

“The one thing that we can do for our kids is bring peace at home,” says Kawtare. “And it starts with us, the mothers.”

Kawtare is co-facilitating the workshop with Somia. She presents in English while Somia leads the discussion in Arabic. The focus is New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), an agency dedicated to the welfare and safety of children. Many of the participants are surprised to learn of this particular government agency.

“How to Raise Healthy Happy Arab-American kids? A Guideline to a Safe and Sane Family Life” reads the first slide of the presentation. I look around the room. Every woman, except for Kawtare, raised in France by Moroccan parents, and a lady whom I later learn is a structural engineer from Iraq, is in hijab. On the teacher’s desk, beside the projector and an HP laptop, sits a large glass jar of lime pickle, a gift presented to Somia by one of the mothers before the workshop.

The ACS workshop has been triggered by the concerns of AAANY members who’ve been reported to the agency by their children’s school. The mothers feel it’s racism, that the school is reporting them unfairly, just picking on them, Somia tells me. “We want to talk about the importance of raising kids in a healthy environment. The parents were raised in a different culture. Their children are immigrants and they’re facing a lot of pressure. They should not fight them at home.”

What is hinted at and covered up in embarrassed laughter is that back home, parents might smack their children for mouthing off and it’s accepted. However here in America, it’s considered abuse. “We need to raise awareness,” says Somia, even as she acknowledges the sting of racism. In one instance, a child fell in the park and his school lodged a complaint with ACS against the parents, accusing them of negligence.

Kawtare begins the presentation by sharing her personal experiences of growing up as a child of immigrants, living in a neighborhood of immigrants, constantly caught between being Arab and French. “The French came to the Maghrib, to the villages, and brought our parents to the factories. They checked the teeth, the muscles. The idea was to bring them to work, to fix up the aftermath of war, and then send them back to Algeria, Maghrib, Tunisia…”

“But what happened? We stayed. And my mother is exactly like you,” she says looking around the room. Kawtare is dressed in a knee-length skirt and short-sleeved indigo blouse, her wavy shoulder-length hair is loose. “My mother kept her culture, taught us how to be Muslims, taught us the language. But in our culture, we don’t say to our children, ‘I love you.’ I was scared of my mom; I don’t want my children to be scared.”

The room erupts in a frenzy of Arabic; participants chatter to each other across the classroom in response to Kawtare’s opening remarks.

“As I grew up I learned that the violence in the street and the violence in the home go together—”

“What does mean violence?” a participant raises her hand. A brief discussion follows in Arabic.

“The one thing that we can do for our kids is bring peace at home,” says Kawtare. “And it starts with us, the mothers.”

“I know that people who look like us—with the hijab or poofy hair or the color of our skin—whether Muslim or Latina—people are looking at how we talk to our children. Because what happens in public is a sign of what happens at home.”

Kawtare became a mother in America three years ago. Alone except for her husband, who returned to work on the second day after their daughter’s birth, she felt deeply isolated. There was no question of observing the Islamic practice of 40 days of seclusion at home that is prescribed for mothers and newborn babies. Then very quickly she found herself juggling many roles: nurse, chauffeur, coach, cook, cleaner.

“Now I understand why my mom was under so much stress,” she says. “I don’t know about you, but I don’t have a big apartment. I don’t have a balcony or garden. I can’t see the sky. Not only that we cannot breathe, we cannot think! So, what do we do to feel better?”

A hand shoots up. “The self-care I do is to come to AAANY!” states a woman in a long black skirt and sky-blue hijab. “When I came here, I learn English. And now I teach literacy class. It supports me, I have more confidence. Because I have more confidence, I go to City Hall and speak out—all from coming to AAANY!”

“That you feel part of the community is helpful, Azza?” asks Kawtare.

Azza nods, beaming.

Weam raises her hand. “I learned many things from AAANY, especially from you Somia!”

I discern Somia’s name invoked over and over in praise as the women respond to Weam’s comment and, in turn, share their own journeys inspired by membership in AAANY.

“When I have a lot of things to do and can’t finish, I feel overwhelmed,” shares Somia. “I like to go to the hairdresser, get a cut, change color— do something new! It gives me confidence!”

“Restoring ourselves, being part of the community, helping each other, getting coffee, wearing perfume, shopping, going for a walk, playing sports—all these things make us feel better!” says Kawtare. “Now that we talk about self-confidence, what can we do to get out of the house and be part of the community and the city and a part of this country?” She pauses, looks around the room which is humming with murmured exchanges.

The women are charged. They turn to each other to discuss the pinpoints in their life which correlate with the presentation. An atmosphere of exhilaration, of affirmation, of lives and destinies unfolding in this makeshift classroom hovers in the air.

“If we belong to a community that makes us feel good, that gives us strength to do things, then we will be better citizens because we will feel mentally healthy,” says Kawtare. “Now that we have kids, we want to give them everything we’ve got: our culture, our religion, our language. If an old person walks in to the room: Get up, give your chair to them. That is what we teach.”

“Number one, we teach them religion!” shouts a mother from the middle of the classroom.

“Arabic language!” pipes another.

A wave of excitement tidals over the group. One by one, the women voice their opinions. A list of priorities is formulated:

- Religion

- Arabic language

- Sports

- Self-defense

- Respect

- Culture

- Prayer

- Self-confidence

A mother raises her hand. “My children tell me everything. What happens at school, what happens on the street, they tell me. My daughter, she says, ‘Even if I make a mistake I will tell my mother so she learns it from me first before anyone else tells her.’”

“That brings us to a very important point. How do we interact with our children? Some of us have young children. If a child has a tantrum in public, lies down on the floor at the supermarket, demanding a toy. What do we do?”

“I’ll buy the toy he wants,” says one mother.

“I’ll take the toy away,” answers another.

“I don’t have enough money. Where am I going to buy this toy for you?” says yet another and the room erupts in heated discussion.

“It happens to me every day,” Kawtare admits. “My three-year old is very energetic. If she sees candy when she’s tired and hasn’t napped, she’ll start screaming. What I do is make myself visible. Because I know people are looking at me. I know that people who look like us—with the hijab or poofy hair or the color of our skin—whether Muslim or Latina—people are looking at how we talk to our children. Because what happens in public is a sign of what happens at home.”

A brief moment of bewildered silence.

“You have to understand when they’re screaming and crying, they’re hungry. Give them a banana!” says Kawtare.

A visibly agitated mother interjects. “If my children hungry, I know! I know, I feel!” she says, pressing her hand to her heart. “I’m their mother, I know what they feel, what they need. I make everything for my family. I don’t send to daycare. My children are with me.”

“We have to stay calm because people are observing and sometimes they call the police,” Kawtare advises. “If a kid is always late and doesn’t come to school, they notice. Our teenagers see a lot on the street, on the Internet. They are under constant pressure. The wars in Yemen and Syria and Iraq… Today they burned down the last refugee camp in France, leaving one thousand refugees in the street… There is pressure on Muslims and Arabs. We can have political stress. Our kids are under pressure.”

Somia distributes an ACS handout, translated in Arabic, which goes over the agency’s services and the guidelines for a healthy family life. A new slide is projected: What are the signs of abuse? Subjecting a child to humiliation, fear, verbal terror, or extreme criticism lists the first of five bullet points.

“As a child of immigrants in France, I know we show love differently. We don’t say ‘I love you.’ My mother didn’t hug me, she hit me. She used to pull my hair!”

“That’s normal!” remarks a mother and the room breaks into exclamations; laughter. A vibrant flurry of discussion ensues.

“If you’re taking care of your kids nothing can happen to you. If your husband does something to the kids and you say nothing, just sitting there watching, then you’re an accomplice. You have to call ACS and tell them what is happening.”

Somia addresses the mothers in a tone that is brisk and efficient. I pick up the words “domestic violence,” “case worker,” “report,” “investigation.”

“Kids have to know Mama and Baba love me, they are on my side,” emphasizes Kawtare. “I’ve seen kids hit at home, hit at religious school. You don’t know Surah Fatiha? Slap. You didn’t wash the dishes? Slap. In school, a kid has problems concentrating, You’re stupid.

“There’s a lot we can do at home by showing love. You can send positive messages to your kids. Your kids need hub! They need love.”

Read Part 1: These Streets are Ours Too

Read Part 3: Working Together As One Hand

Read Part 4: A Spirited Sisterhood