I traveled to the heart of the epidemic one day in July to find out for myself what kind of peril we’re in.

July 25, 2014

Parents, lock your doors and hide the kids, because a new danger stalks the streets of Manhattan. It’s an addiction, mostly known to afflict males, and it’s been spreading its tentacles westward from Japan since 1999. Its name is Yu-Gi-Oh! and it lies at the center of an ongoing conflict between business owners and young men on a one-block stretch of Mott Street in Chinatown.

I traveled to the heart of the epidemic one day in July to find out for myself what kind of peril we’re in. Standing on the sidewalk, I met André Holly, who explained how it works.

“So, you have 8,000 life points, and each player tries to decrease the other guy’s life points to zero. It’s based on a TV show called Yu-Gi-Oh! The main character is named Yugi and there’s a bad guy who says he’s going to take over the world with these cards.”

André Holly buys, sells, and trades Yu-Gi-Oh! cards. The game is based on a Japanese manga of the same name, and was listed by Guinness World Records as the most popular trading card game in the world in 2009. In it, players use “monster” cards to attack opponents. They can also use “spell” or “trap” cards to boost the strength of a monster, draw more cards, or redirect an attack back at their opponent.

The 20-year-old Holly is one of 10-30 young men who stand outside of Chinatown Fair, a video arcade on Mott Street, every Friday afternoon, clutching binders filled with Yu-Gi-Oh! cards.

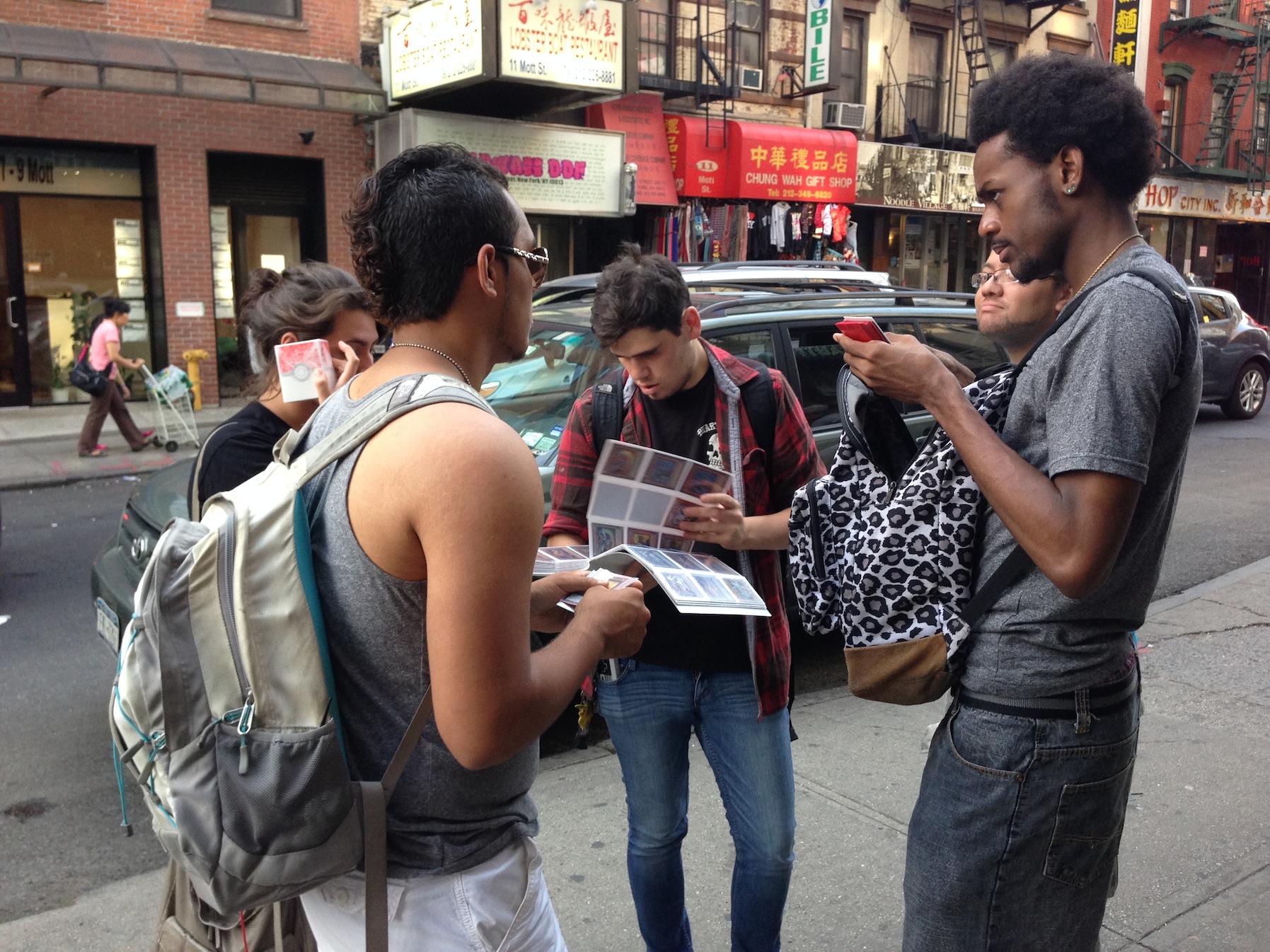

The 20-year-old Holly is one of 10-30 young men who stand outside of Chinatown Fair, a video arcade on Mott Street, every Friday afternoon, clutching binders filled with Yu-Gi-Oh! cards. As we spoke, two kids – students from a nearby high school – approached and asked to see his binder. All around us, young men were negotiating:

“You got any dragon shrines?”

“I got a blue dragon.”

“Anything else?”

“Do you have a gold star?”

“Yo, you got a common gold star?”

“I have super.”

“He has a gold star for $2. It’s not mint, but it’s good.”

“I’ve made a lot of friends through this. Like him – he’s one of my best friends,” said Holly, and gestured at the guy standing next to him.

The other guy looked away, his hands in his pockets. “I don’t play this that much anymore,” he said.

Holly rolled his eyes then gave me a look that said: not true.

A curly-haired man with ear buds tucked above each ear waved his hands at us: “Guys, can I just ask you to move over here? Because the owner is coming soon and we don’t want to block the entrance.”

“But these Yu-Gi-Oh! kids, they’re like bees! They come back to the hive eventually, no matter what!”

The curls belonged to Ralphie Reyes, a restaurant worker who, at age 27, is the default den father to the group. When Holly’s friend began blasting loud music, Reyes frowned and made a neck-level “cut it out” gesture. The music stopped.

“I’m the oldest one here so I try to make sure we’re all respectful. Like the old lady who just came out of here?” He gestured at the entrance behind him, which was marked with dentists’ names in English and Chinese. “She’s the owner of this building, so if she needs anything done, we try to help her out.”

Lonnie Sobel, the manager of Chinatown Fair, has a different take on this scene.

“These kids took Chinatown Fair out of business,” said Sobel in a phone interview. He was referring to 2011, when the arcade closed. Sobel bought and reopened the business in 2012. Initially, he tried to make the teen hangout more of a family destination, but said that families were put off by the crowd of young men.

“I’m the oldest one here so I try to make sure we’re all respectful. Like the old lady who just came out of here…”

“We’ve had to call the police anywhere from 50 to 100 times to get rid of them,” said Sobel. Two stores next door to and across from Chinatown Fair sell Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, and in Sobel’s view, the young men were there to steal business from those stores. “It’s illegal what they’re doing: they’re running a business in front of my business and not paying any rent.”

There’s also a third Yu-Gi-Oh! shop called Nebulous on nearby Elizabeth Street. Holly told me he doesn’t like that shop. “They’re kind of uptight. Personality-wise I don’t like people who are snobby.”

Sobel once took a petition to get rid of the crowd and said that all 29 businesses on the block signed it. “But these Yu-Gi-Oh! kids, they’re like bees! They come back to the hive eventually, no matter what!”

“We ask them to go across the street and when they go across the street there’s no problem,” he added. “But unfortunately, across the street doesn’t want them either, and they call the police even more often than we do.”

None of the men I spoke to knew of any recent clashes involving police. But several of them remembered an incident from years before when several people had been arrested.

“I didn’t believe it when I heard about it,” said Holly. “Because it’s like – over that? It’s not that serious, you know. It’s just cards.”

“I wasn’t here but I heard about it. One time there was a whole lot of people here, being loud. They asked them to move, and they don’t wanna listen, so they called the police,” said Reyes. “It’s like the no loitering thing. I can understand why business owners don’t want us to block the entrance.”

“I didn’t believe it when I heard about it,” said Holly. “Because it’s like – over that? It’s not that serious, you know. It’s just cards.”

Meanwhile, Sobel regularly attends a monthly Fifth Precinct police-community meeting hosted by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, where he says the Yu-Gi-Oh! issue is often discussed. A Chinese-language paper, the World Journal, has covered the conflict. Sobel also said it’s discussed by the neighborhood association.

“We had an email going because we were trying to think of somewhere else they could all go, and I mentioned the park,” said Sobel. “And this one woman emails me and says, ‘If you send them to the park I’ll shoot you! That’s where I do my taichi every day!’”

Sobel’s greatest hope now is for the police to repeat a tactic they used once before: get someone who looks young to go undercover, and catch some kids taking money for the cards.

“Years ago, if you went to the police and said listen, there’s 30 kids hanging out, they’d go and they’d give tickets and make arrests. But they don’t do that anymore,” said Sobel. “Now unless they can catch them specifically trading the cards, they say: listen, we can’t just chase those kids for hanging out.”

[editor’s note: this article is part of our series “Souvenirs,” uncovering stories of found objects in the city]