The author of A Good Country talks about the final novel in her Kurdish trilogy, tribal longing, and the work that entertaining literature does

September 29, 2017

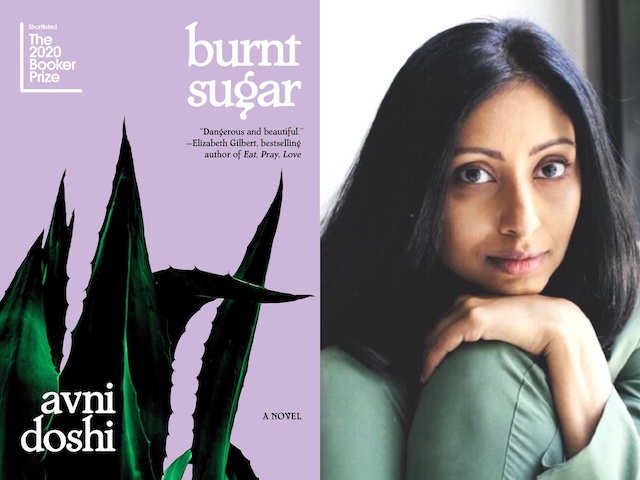

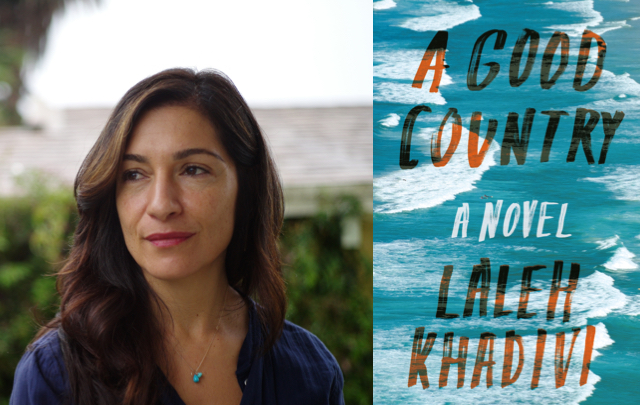

Laleh Khadivi’s latest novel, A Good Country, is the timely and powerful final piece of her Kurdish trilogy, following Age of Orphans and The Walking. The novel follows Alireza Courdee as he searches for community as the son of immigrants in an affluent SoCal suburb. To fit in, he shortens his name to Rez to make it easier to pronounce, he experiments with drugs, and he parties with surfers. After falling out with the group over a botched surfing trip to Mexico, he begins to connect with Muslim kids who are like him, though they are more comfortable in their skin. Following a terrorist attack and the ensuing backlash, Reza and his friends are drawn to the call home of a terrorist group that promises a good country, one where a Muslim man can be part of a community, one where Reza may finally belong.

I met Laleh through mutual friends. We are both Mills alumnae living in the Bay Area, writers from Muslim countries who write about people from those experiences, Bay Area artists who are passionate about art—so it feels inevitable that we met and became friends. As a writer I admire, she is a person I turn to for advice and insight about the writing world and the importance of art. We spoke on the phone about her most recent novel, which portrays complicated characters with compassion and without judgment, and the struggle to balance beauty and entertainment in a creative work.

Kirin Khan

Outside of identity (Kurdish, Iranian, Muslim/Shia, etc), what would you say are the common threads throughout your trilogy?

Laleh Khadivi

The trilogy is a project less concerned with identity than it is with belonging. I wanted to take those definitions down to their base level. If identity is a way we announce our grouping or stature, then belonging is something that happens to you. You belong to a family, a people, belong to land, time in history and so on—it happens without your consent.

I’m interested in what happens to our sense of belonging as our lives change—what happens in migration when we flee places to which we swore allegiance? How do you notice yourself belonging as an immigrant? The trilogy explores being in a tribe versus being a citizen of a nation, being Iranian versus Kurdish, how we adapt when we are separated from our people, whoever they are. We are seeing a kind of post-national belonging, which has to do more with your class and race, your mobility. The internet, for example, is an open, borderless world. What happens when anyone can access the borderless space?

In the trilogy, I wanted to make a circle following belonging: first the grandfather lived in Kurdish tribal land (what is now Western Iran) and belonged to a community of people who lived there for hundreds of years. He is torn from that and forced into Iranian citizenship. In the next generation, his son immigrates and seeks to belong in the US, and then Reza seeks the tribal belonging of his grandfather again, a belonging that will not shut him out.

KK

When I heard that your book was about a young Muslim man who becomes radicalized, I assumed he joins ISIS. This seemed tricky, since Reza, like the characters in your previous novels, is Kurdish, Iranian, and presumably Shia, while ISIS is an anti-Kurdish, anti-Shia, Sunni extremist group. Upon reading the book however, I realized Reza joins an invented radical group based in Syria. Why use an imagined group instead of a real one like ISIS, which is the dominant terrorist group in Syria?

LK

That’s right, he doesn’t join a group that exists now. It’s based on a million different groups. I wanted to avoid echoing what we read about in the newspaper because that comes with all kinds of connotations, and I wanted to tie this story more directly to my notion of belonging. I don’t get into the minutiae, because that’s not how recruiters work. What’s being offered to these youths on the internet is not Sunni radicalized Islam, it is the idea of a place where an Islamic man can be respected. It is mostly tied to the idea of a call home. I wanted there to be a group that said, “Listen, you’re never going to make it as a full human being where you live. If you come back here, you’ll be given the dignity that you deserve.”

KK

The desire for a call home is so relatable. I think a lot of people are looking for that in one way or another. Do you think you lose something when you get really specific and contemporary? Say the time of ISIS is over, there will always be that next group, whether Muslim or something else.

LK

Yes—regardless of what groups are making the news at any point, there’s always going to be that desire for the tribe. This sensation is part of our humanity. We are trying to move into beautiful pluralism, but we are having a hard time. Look at elections all over the world. There are ways in which our tribal longing really pulls at us because actual pluralism is untested. There’s never been a human society that has accepted pluralism of the sorts the United States is attempting now. People go to what they know.

He (Rez Courdee) wants something that is open to him and will not shut him out based on his language or appearance. In joining this group, so long as he becomes Muslim, he can have access to this great belonging, this great acceptance. That’s what the tribe is. It’s interesting that in this pluralistic country, often when people try to belong to more than one tribe, they must forego the other one—there are ways in which tribe can be an exclusive sensation. I was trying to draw out a way in which he has to forego the things that he knows for this great unknown. He can’t have both at the same time. In different ways, each novel in the trilogy asks, how much are you willing to give up to belong?

KK

This book humanizes people who are currently experiencing marginalization, focusing on a disenfranchised child of Muslim immigrants. Is it actually possible to get people who don’t recognize the humanity of Muslims (or any subgroup of people) to do so through art? Or is that a lost cause?

LK

I don’t think it’s a lost cause. It’s very hard, but why would you write or make art otherwise? We are a curious species; we can’t help it. Once we feel safe, we are willing to explore. I had to do the work to craft a believable conversion, so we can begin from a place of recognition, not of demonization. I wanted to show how it’s possible for soul to be pulled from one thing to another. What is the balance so that people will not make a quick judgment? You have to tell the truth as you understand it and recognize that all story is made up of equilibrium—for every asshole who beats his wife and is Muslim, there is a counterweight in that same community. The gods of beauty and terror are in the same story.

The character is not a suicide bomber. He just wants to join a group that will respect him and his way of life, but who knows what would be asked of him in the future? For someone to tie their life to such violence, something is wrong in the equilibrium. I would challenge myself to write a similarly complicated truth about a member of the religious right or a very conservative organization in this country. Because that is the writer’s job to go into the hornet’s nest and say, “I have to figure out how this works, and I have to do it without judgment.”

To craft a beautiful character that breathes is difficult. And then, what is even harder is to make it entertaining. That’s where people can meet, once we are seduced by entertainment. When people are entertained, they listen. That’s all I can ask for. We underestimate the deep wells of compassion within people. We live in a fractured world, and we have to reach across artistically. This is what literature, at its best, does really well—it communicates humanity to humanity, and it does so while entertaining. There is no other way to get the heart to unlock.

KK

What does it mean to entertain? How do you write an entertaining book while maintaining a level of artistry to where it’s still literature?

LK

You work really hard. I had to drop the bar for myself when it comes to artistry, not completely but I had to lower it. Let yourself make a sentence for a regular person. I pay loyalty to what the story needs and less loyalty to artistry. I can’t drop the art completely because I love literature and language too much, but if it doesn’t serve the story, it doesn’t belong.

You have to pay attention to what is alive. You tie yourself to an obligation to light up each page that extends beyond writerly craft, an obligation to create momentum so that the reader wants to get to the end. I looked at books that worked in that way when I read them. I read Salinger, books about adolescence because my book has a lot of adolescence in it, Toni Morrison’s Jazz, Mystic River. When I was pregnant, I read Gone Girl, which is not the kind of book I usually read. Reading it was like being nine years old again, I was so thrilled. I was flipping pages, being pulled along by this energy of entertainment, always asking what happens next? I remember holding the book and thinking, how does she do this? Gillian Flynn gets something about storytelling. It is much harder than spinning the beautiful paragraph, to get this thing to have an engine inside of it.

When working on this novel, I thought about entering the space of taboo, about the balance between levity and darkness. I looked at comedians because comedians understand pathos viscerally, and yet they make jokes. How do you do that? Keep it simple, no tricks, keep it light and moving. Comedians are some of the smartest people alive, because to make something really funny, you have to see all angles. You cannot be hung up on righteousness.

KK

How do we apply that to our writing?

LK

The parallel of that in the novel and story is that the writer comes from above everything, not from in it. The training of a comedian is so brutal that by the time they actually succeed, they have taken so many risks and failed that they’ve gotten used to it, to where they aren’t afraid to take risks and fail again and keep trying until it works. Because the writer doesn’t have this kind of direct relationship with our audience, we tend to be more cautious. Caution is what makes writers suffer for longer and not get the big truth. We have to be willing to take risks, to fail.