An interview with Ali El-Chaer

February 16, 2024

Last May, I edited Love Letters, a folio of twelve flash fiction pieces featuring art by Ali El-Chaer. In the months since the folio was released, Ali and I have kept in sporadic contact online, often asking one another how we were caring for ourselves, whether we’d eaten. Still, when we met for an interview this week, talking in person for the first time in months, there was a lot to catch up on. Ali casually referenced their fiancee, who I remembered from the last time we talked as someone they were dating (Ali had not been enjoying their book recommendation but had been enjoying his company). They had just gotten back from their partner’s group exhibition In Relation at the TERN gallery based in the Bahamas. In the first thirty minutes of our call, we volleyed between a high-spirited discussion of the neocolonial structure of Caribbean tourism and life updates.

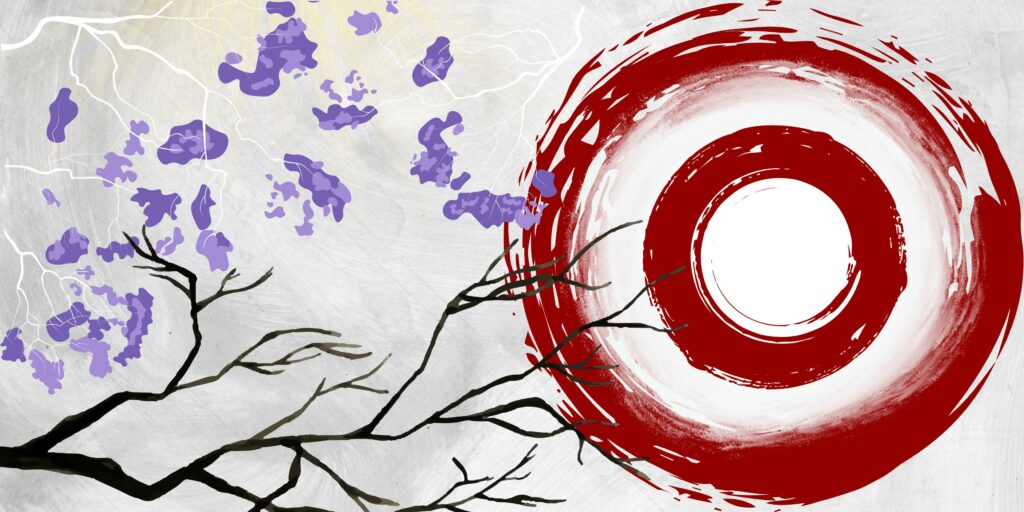

For several months, Ali has been working on a series of three paintings incorporating figures from both Christian iconography and Palestinian resistance. In my first interview with Ali in May 2023, they had said: “If I am choosing to paint, it is often because I am having quick, intense emotions I just need to throw out there.” One of the paintings in their series is pictured above and becomes the framework for the following conversation between us, as we revisit conceptions of love as they are shaped irreversibly by the present—the recent attack of approximately 1.4 million refugees in Rafah, the fast genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza, and the seventy-five-year genocidal settler colonial project and occupation of Palestine.

Below is an interview with Ali El-Chaer, a Palestinian visual artist and organizer based in Nashville, Tennessee, and my friend.

Yi Wei

At the time the folio was first published, your tayta was in hospice and we spoke over the course of our collaboration about how the art was patterned with the love and grief you were holding for her through the process. Now we return to a piece with another grandmother, Saint Anne, who you say kept showing up for you in your everyday life.

Ali El-Chaer

Yeah. I actually hadn’t actively thought about it initially. It wasn’t until you said it that I was like, oh wow, the timing really is weird. I had kept seeing Saint Anne stuff everywhere I was looking. I was seeing the words Saint Anne, I was seeing books about Saint Anne, I was seeing her symbols. Or just the word Anne, Anne, Anne, everywhere. And so it was an unignorable thing that was repetitively coming up. Even to the point that when we went to the Bahamas, the church I was staying next to was the Saint Anne Anglican Church.

Something that had really bothered me when my tayta was in hospice was that she really was the last, or one of the last, people in my family that saw our land before we got pushed into the refugee camp and then pushed out into America. I think that’s why I’m locked in on her right now, because of the genocide happening. For a lot of people, they’re probably having a similar situation where there was one person staying on the land and they’re finding out about their grandmother’s passing through Instagram graphics or just loss of communication where you can only assume what happened. The building on the left in the painting is Omari Mosque in Gaza, which was once a Byzantine church and was recently destroyed. The Orthodox church on the right is from my village, Al Bassa in Akka, that was destroyed in August. In 2023, they tore it down, and that was the year my tayta died. I felt like she died with the church.

Every time a massacre happens, I just feel like my family is dying over and over and over again, on this cycle. It feels like this weird cusp of we’re almost there, if we just push it a little bit harder, we will be free. But then, I wish we would’ve been free sooner.

YW

Who are the religious figures in this painting? How do they fit into the endeavors of your work at large?

AEC

The two figures in the painting are Saint Anne and Mary, so a mother-daughter relationship or in the completion of the series, a grandmother-mother relationship. Saint Anne’s icon is her with Mary, holding a book, typically, with their halos always touching. I didn’t include a book because I wanted to substitute it with Mary reaching out to Saint Anne. My art on a larger scale deals with intense interpersonal emotions as well as storytelling and reclamation. In this case, my family are Melkites, another form of Orthodox. The deep desire to take back what has always been ours from the colonial narrative is more important than ever to me.

A significant part of my work is working with that because the Bible happened in Palestine. In a way, it is sort of a reclamation of, the British took it and they fucked it up so much. It’s our responsibility, as Palestinian Christians, to take ownership of how it was used badly and make up for that for the people who were harmed by Christian missionaries but also reclaim it as what it was meant to be. We need to revisit our past and authentically connect with our ancestors rather than trying really hard to push away. I see a lot of people saying, “I’m doing ancestor work but I’m going to do this thing” that I’m like, your ancestor would’ve hated that. You can’t do ancestor work and then do what they would’ve hated to avoid accountability or discomfort. So that’s why I wanted to do Christian iconography because it is that reaching back.

YW

The faces in your series of paintings are blurred intentionally—can you tell me more about why you made this decision and what brought you to it?

AEC

Yeah, it was a conscious decision. There’s two other pieces in the series. The first one is Saint Anne if she was a member of the Chrysanthemum Flowers (Zahrat al-Uqhawan), a women’s association that became a militant group in 1947 in Palestine; and then the second piece is this one, of Saint Anne and Mary; and then the last piece is Mary with Jesus in her womb.

The imagery that came out last December of the men being stripped was so—one of the most horrific things I’ve seen come out of the war. There’ve been a few images I’ve seen that have become very haunting and that was one of them. So I obscured the faces in the paintings because there’s this moment in the culture where I feel like we’ve all lost ourselves. We’ve become kind of melded together and whenever I see any mother, any child, any man being hurt, it just feels like I’m dying or there’s this loss of identity happening where it’s like, I have felt, especially the last few months where Palestinians all over the world are being attacked in different contexts, it feels like we’re all just born to die. And so the obscuring of the face is this loss of identity that comes when people no longer view you as a human but just as a martyr.

YW

When we talked before this call, you mentioned that the paintings in this new series remember generations of love and loss. What have you been thinking about or feeling through in regards to love over the past few months?

AEC

Yeah! It feels really transparent in the image where it’s mother and child. I’m always a sucker for mother-and-child motifs, but I wanted to do something like how so many of the stories in the love folio were talking, grasping about love through different generations. And the timeline where love evolves. When we started collaborating on the art for the folio, I was really excited because oftentimes, when I see work about love, it’s romantic. There’s not a lot of space for the bad side of love or the growing pains or the forgetfulness of love.

Over the last few months, I am seeing all these images of bodies piling up, at one point finding out through an Instagram graphic that my friend and her daughter were killed a few days after her daughter’s fifth birthday. Everyone had pulled what little resources they could to make her a cake despite the genocide. They were bombed together in the early morning.

Initially when we started the Love Letters folio, my tayta was in hospice in our house. As I was making the art, there were often these breaks to go see: is the end now? Once death was at our door, it was early in the morning and it was in fact our dogs that woke me up to push me downstairs. It has been a year since my tayta has passed and I think about how, if she just came back spontaneously, would I remember how to love her the same way? And I don’t know. When she passed, too, you know, it was me and my mother who cleaned her body. And I think that was the most loving thing I’ve ever done in my life.

Ali El-Chaer (b. 1995, they/he) is a trans diasporic Palestinian illustrator and painter, currently living in Nashville, Tennessee. They received their bachelors in fine arts at Austin Peay State University (2018) and has since gone on to show their work in Jordan, South Africa, and New York. He has worked as assistant at Turnip Green Creative Reuse, the Frist Art Museum, and the Tennessee State Archives and then founded a community collective called Nour Nashville, catering towards political education, organizing, and outreach.

His present work has transitioned into tackling intense interpersonal emotions around the ongoing Palestinian genocide and continued displacement, pulling from archived political posters, Byzantine art, and Fayum mummies. Through their engagement with history, he has been able to reclaim and uncover lost traditions or books and offer it back up to a Palestinian audience; in one instance finding a lost portion of his family to reconnect with.