The layered histories of Black and Asian communities in the Queens neighborhood.

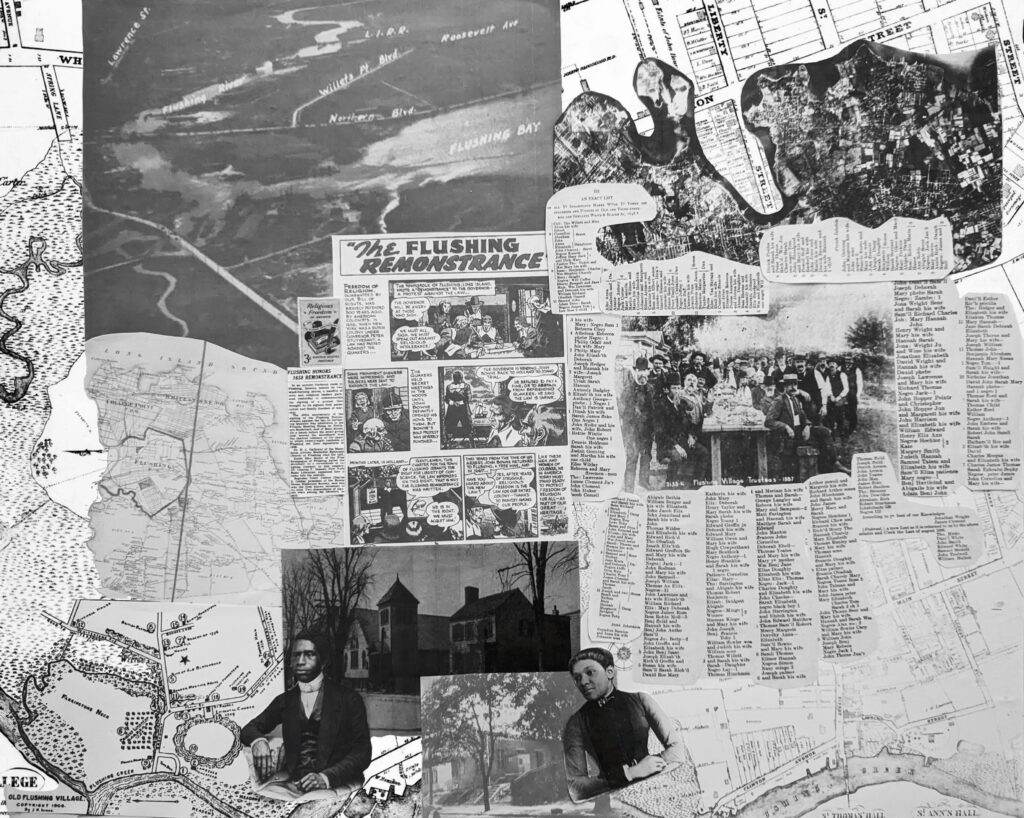

The neighborhood of Flushing, Queens, has many layers of soil. The soil on which the Matinecock people lived for generations and fought physical and cultural erasure. The soil where Free Black and Quaker communities in New York were built. The soil where Black people were laid to rest and the soil that buried traces of their history and existence. The soil that nurtures the commercial nursery and community gardens. The soil that gives foundation to the current vibrant Asian communities in Flushing and the soil that will soon displace neighbors for luxury development. The soil that supports the ecosystems of Flushing Bay and Flushing Creek, and the soil that was used to fill in the creek to make land.

As friends and collaborators that come from the Black and Asian diaspora, we wanted to explore the histories of Black and Asian communities that have called Flushing home through our writing and art. As urban planners, we were curious about the spatial politics that drive settlement, segregation, and displacement in the built environment. Few neighborhoods in New York City have Black and Asian communities living side by side. In the 1980s, Flushing’s Black and Asian communities represented almost one third of the neighborhood’s population. To better understand that evolution, we went on walks, dug through historical texts and images, and pondered what the fragments might tell us about how neighborhoods change and what gets forgotten.

When we walk through the neighborhood together, it feels like steeping a pot of tea. Different elements and aromas of Flushing are slowly revealed through self-reflection and stillness. Walking with each other widens the aperture of what we each can see. One of us might notice something the other may not, or a tree or store sign might bring to mind a personal story or anecdote. In the end, we see and understand a place far better than if we were alone.

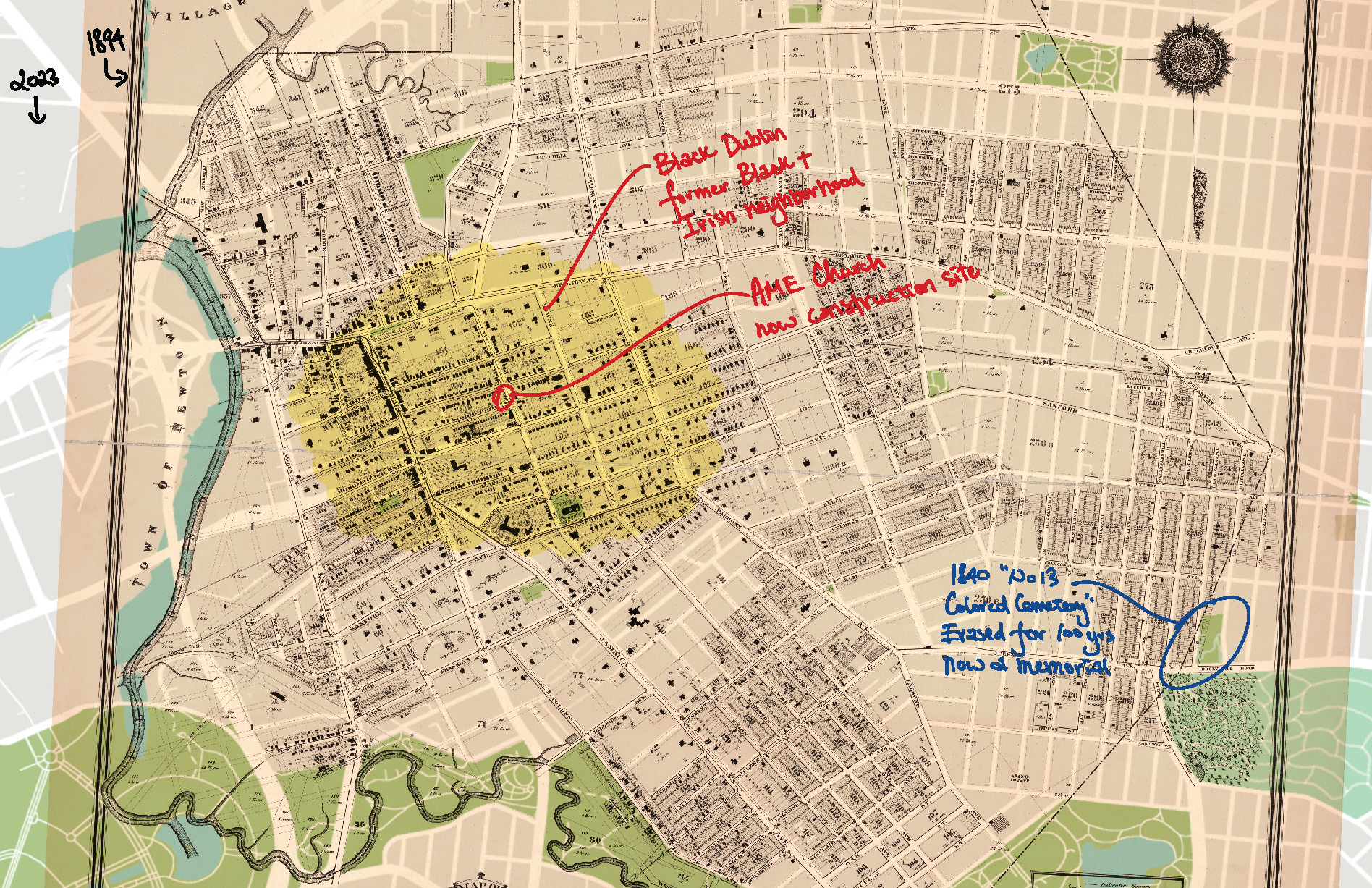

Black Dublin

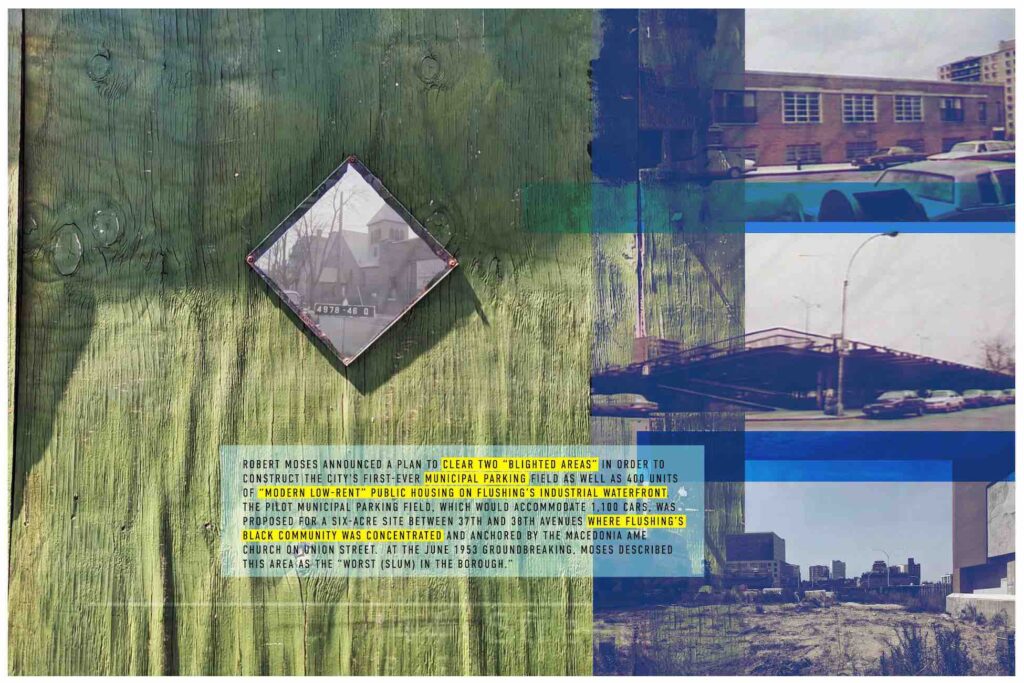

In downtown Flushing, we came across Black Dublin, a Black and Irish community started in the 1800s. Black Dublin was a self-sustaining community with homes and small businesses, all anchored by the Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). Founded in 1811, AME likely served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. In addition to being a central part of Black life in Flushing, it also served as a burial ground for Black residents at a time when there were no public cemeteries. It’s not clear how many people were buried at Macedonia, but in the 1930s, two hundred bodies were discovered during a church expansion project. The church wanted to relocate the bodies to the nearby Flushing Cemetery but was blocked because of a lack of death records for the deceased. The bodies were reinterred at the church. Over time the church and Black Dublin faced the impacts of urban renewal. In the 1950s, as part of a wider “slum clearance” initiative developed by Robert Moses and Queens Borough President James A. Burke, the area surrounding the church was turned into a municipal parking lot. AME relocated to a space in Jamaica, Queens.

Gloria

Whenever I visited New York in the 1990s and 2000s, my relatives told me to visit the “modern” Chinatown in Flushing, a neighborhood with recent developments that resembled Hong Kong, where I grew up. The so-called resemblance lay in the contemporary buildings with large glass windows, bustling commercial streets, and air-conditioned shopping malls. Flushing for a long time was a place where I went to see family friends from Hong Kong and to consume a Hong Kong–style dessert, something from the newest Chinese chain, or a particular snack easier to find in the neighborhood. I didn’t think about what came before, an assumption rooted in my ignorance, my lack of curiosity, and the systemic erasure of history.

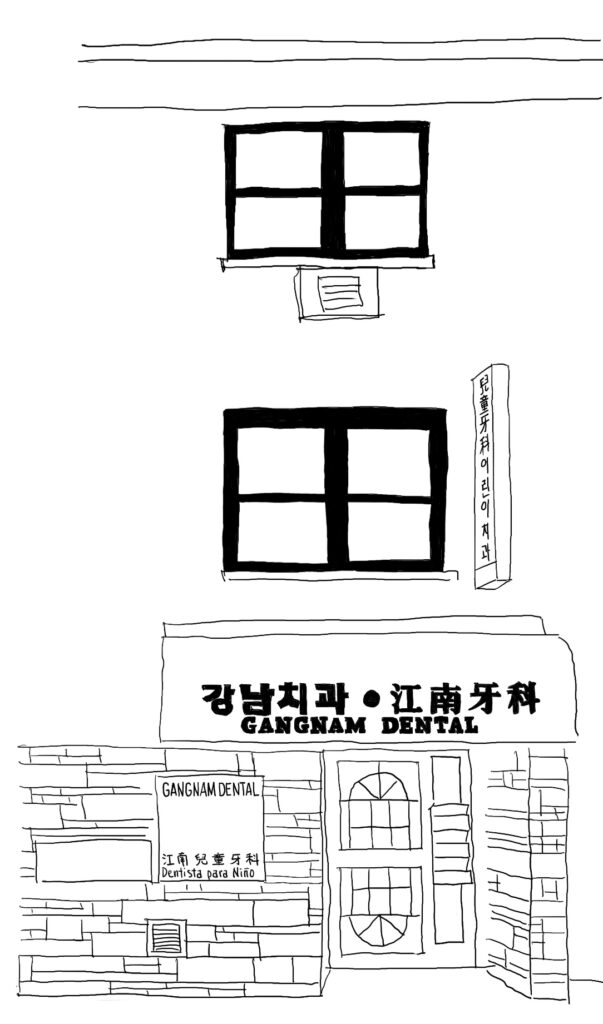

Filled with histories I had learned, I recently went to Flushing and saw it differently. I walked beyond the major corridors designated by the yellow hatch on Google Maps. I walked past townhouses, decades-old apartment buildings, and doctor’s offices with signs in Chinese, Korean, and English. The southern part of the neighborhood is lined with businesses using South Asian languages, the northern part by light industrial uses, like stores selling granite and metal fencing.

I went to see where AME and other erased sites once stood. I found unassuming buildings and lots punctuated with markers belonging to the Flushing Freedom Mile. The signage marked sites that served the African American community—AME and the Flushing Female Association Schoolhouse—and one for Lewis Howard Latimer, an influential Black inventor. But no signs told the story beyond the sanitized view of freedom in Flushing—no text on why AME was torn down, no explanation on the erased African burial ground, and no story about how Flushing became a predominantly Asian neighborhood.

I researched more about the 2004 Downtown Flushing rezoning to provide “opportunities for high-quality, mixed-use development” and “enhancement of public spaces and waterfront access” and the 2019 Special Flushing Waterfront District Plan to create a twenty-nine-acre waterfront district including luxury condos, hotels, and retail stores. I came across a 2020 report from the Municipal Art Society of New York that stated: “Over the last ten years, Flushing has experienced a wave of new condominium construction surpassed only by Williamsburg, Brooklyn.” The resemblance to Hong Kong is only signified by the growing number of glassy buildings and the facade of robust economic development. The focus is not on the small local businesses and homes that were replaced or the communities that were displaced. Not in Hong Kong. Not in Flushing.

In 2021, local community groups such as Chhaya CDC, MinKwon Center for Community Action, and the Greater Flushing Chamber of Commerce banded together to fight the gentrification of the Flushing Waterfront. The group is suing the city’s Planning Commission, Department of City Planning, and the City Council, alleging that the city approved the project even though the developer had not provided an environmental impact statement, and therefore failed to account for the development’s potential impact on the local community. With projects such as these, whose versions of history and the future are being told and upheld?

Daphne

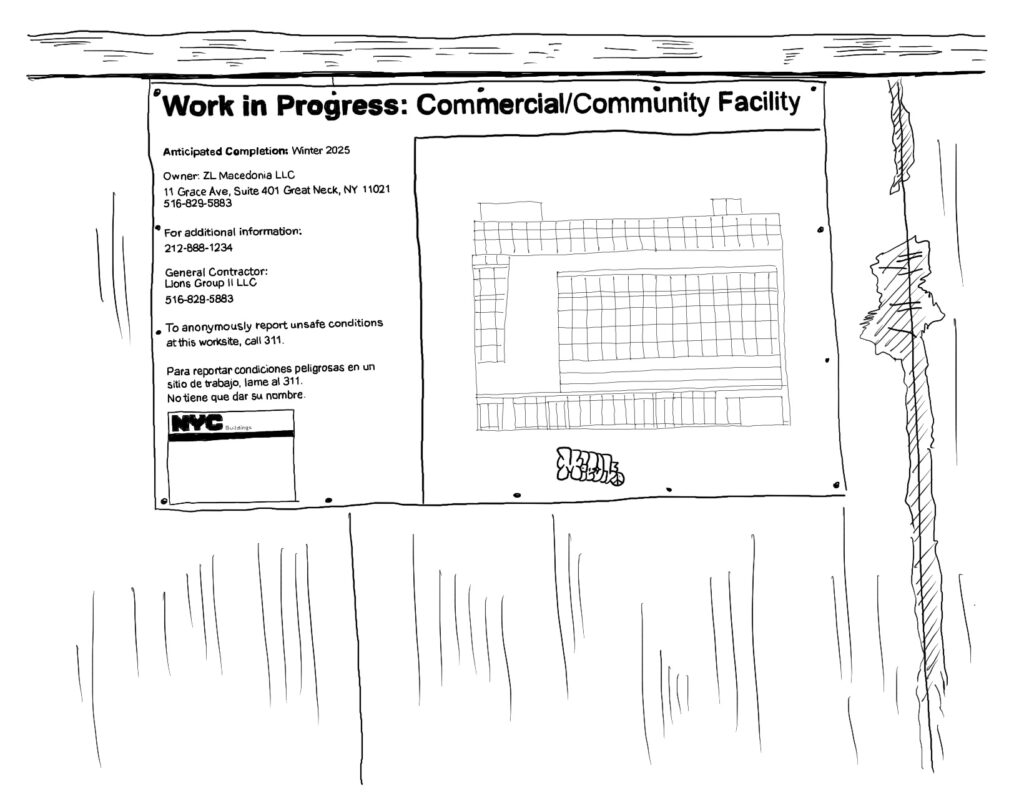

In 2013, the Bloomberg administration passed legislation that required building owners and contractors to display signs describing development activities in their neighborhood. The standard blue signs read: WORK IN PROGRESS: COMMERCIAL, WORK IN PROGRESS: RESIDENTIAL, WORK IN PROGRESS: MIXED USE.

The declaration of progress is often accompanied by a rendering that shows us the future. The new law also required development peepholes: small diamond- or square-shaped cutouts in the construction fencing so the public can look at the site as it changes. Both the sign and the peepholes are meant to reveal information, but often, they leave me asking more questions.

The site of the Macedonia AME is now a vacant lot wrapped in construction fencing. The blue signs tell me that in the future, when all the progress has been done, it will be a commercial/community facility building. The past is still somewhat present; the owner of the site, “ZL Macedonia LLC,” is a limited liability company that was established in 2018. If all goes to plan, the Macedonia AME, which is currently located in Jamaica, will return to the site with new neighbors. The ease and speed at which Black spaces can be demolished, relocated, forgotten, and erased is spatial mercuriality.

Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground

Further away from Main Street, we are drawn to another site of burial and erasure: Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground. In 1840, the Town of Flushing purchased a plot of land to create a public burial ground. The site became the resting ground of mostly Black and Native American residents. On some historical maps, the burial ground was named “Number 13 Colored Cemetery.” When the Town of Flushing became a part of the City of New York in 1898, much of the history of the site was erased. The site was transferred over to the NYC Parks Department and became a playground that was renamed Martins Field. In 1990, local activist Mandingo Osceola Tshaka gave voice to this erasure and secured funding for an archeological study that identified those who were buried there. The city eventually made changes to the playground to minimize further disturbance to the burial ground, and in 2021, dedicated a memorial to the African and Native American people buried in this once-forgotten ground.

Daphne

For five years, I worked near the African Burial Ground in Lower Manhattan, a multiblock area that was the final resting place for an estimated twenty thousand Africans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was located in what was then a neighborhood of freed slaves. A neighborhood that was paved over to make way for the expansion of lower Manhattan, much like Seneca Village was demolished to make way for Central Park. A history that was only discovered after excavation began for a new government office in 1991.

Ever since I learned this history, I have followed news story after news story of African burial grounds being discovered in New York City. A burial ground under a park in Flushing—Old Towne of Flushing Burial Ground. A burial ground in my neighborhood of Flatbush under a vacant lot slated for housing development.

I think about the burial grounds that were never lost. The wrought iron fencing clearly delineates the land of the living from the land of the dead. The tombstones and mausoleums, the names of loved ones lost, etched forever in marble and granite.

Entering the Flushing Burial Ground feels like stepping into a meditative space. It is a place where silence and slowness bring comfort. In the center of the park, a monument lists the names of hundreds of people who were interred there. The last section is blank, leaving room for future discoveries and the names of the once-forgotten dead to be properly remembered.

Being a Haitian American born and raised in New York City has shaped my understanding of Black impermanence, and how Black culture, spaces, and histories can be erased. How communities can disappear through gentrification and displacement, and places can disappear through natural disasters and environmental degradation, through colonial resource extraction. I think to myself, what does true peace look like in life and death?

Gloria

If you walk toward Flushing Bay on Northern Boulevard, near the on-ramp to the Expressway, you will see a two-story building with green awnings and a slanted roof similar to one you might find on top of a Chinese pagoda. The large dark green text on the building, a Chinese funeral home, reads “Chun Fook Funeral Services, LLC.” Situated on a big corner lot, the building catches my eye whenever I visit the area.

I have always been fascinated by the ritual and preparation to honor the dead in Chinese culture. Twice a year, at Qing Ming and Chung Yeung festivals, my family prepares food and burns paper to honor my grandparents and great-grandparents. The rows of tombstones along the steep slopes of the hills of Hong Kong captivate me.

My maternal grandfather was buried in Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery, in a section that I crudely coined the “Chinese corner.” A significant number of Chinese families have interred their dead at the historic cemetery, perhaps because of its proximity to Sunset Park.

On an April visit, I saw remnants of paper and candles on the ground in the area of the cemetery designated for Qing Ming rituals. As I headed home through the cemetery, I visited the ongoing project unearthing unmarked African American graves further south. On a more recent visit with my mother on Chung Yeung to pay respects to her father, we came across preparations for Día de los Muertos at the cemetery. We remarked on different cultures’ shared rituals to remember their ancestors.

For me, cemeteries are places that honor the dead. They are places of remembrance and expressions of grief and family histories. In considering the growth of the Asian population in Flushing, I can’t help but think of places like Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground, where for so long the dead were forgotten and the living were denied a place to honor their families. I was told that Hong Kong immigrants have improved Flushing, making it denser and more vibrant—a little Hong Kong. We never talked about the history we were building on. Nobody knew or talked about what the soil had seen and what it had buried.

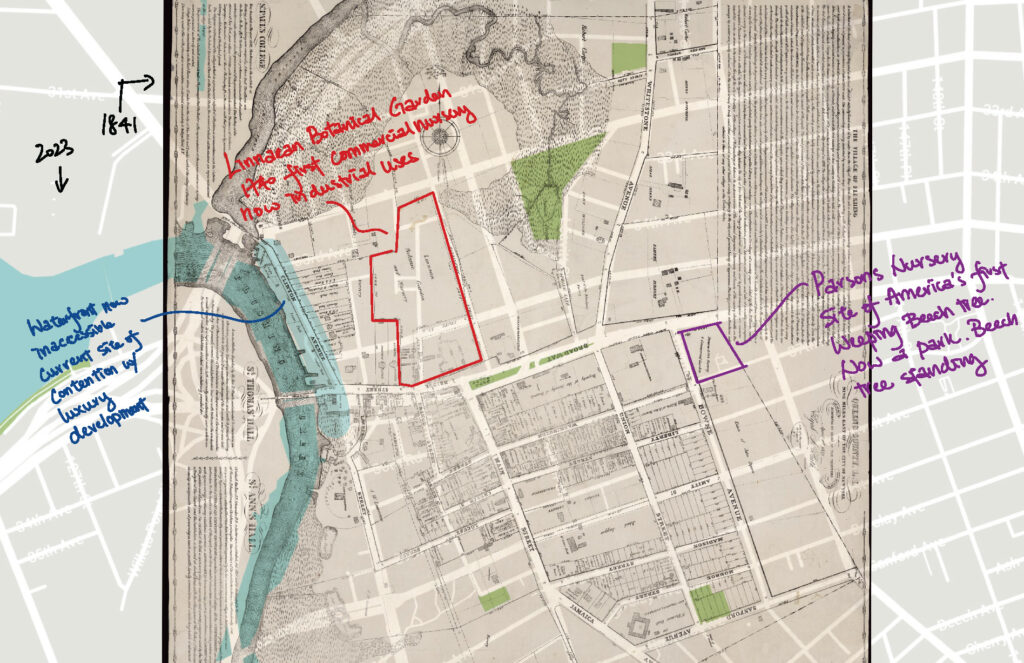

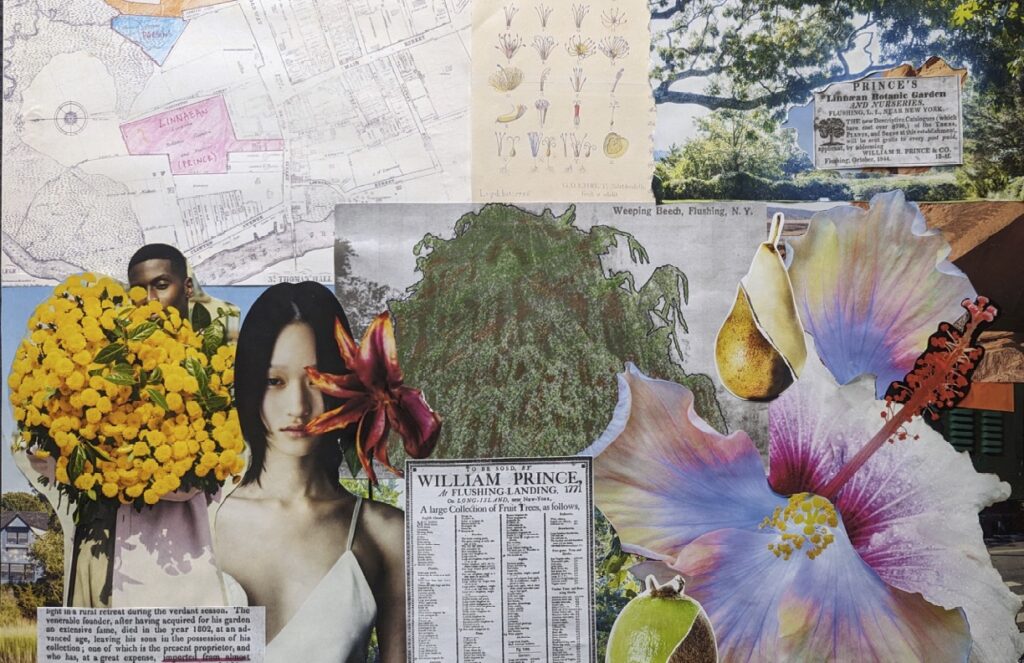

The Weeping Beech Tree

The Weeping Beech tree was one of only two landmarked trees in New York City. Samuel Parsons, a nurseryman and a landscape architect, obtained a cutting from a Weeping Beech tree in Belgium and planted it in Flushing in 1847. The tree and surrounding area became Weeping Beech Park in 1945. Parsons was a big part of the botanical history of Flushing: in 1868, he opened Parsons Nursery, which remained in operation until 1901 and helped establish commercial nursery trade in New York. The nearby Prince’s Nursery, later known as Linnaean Botanic Garden, was established in the 1740s by Robert Prince and his son William Prince. It was America’s first commercial nursery and became the largest supplier of fruit trees and grapes at its time. It closed in 1869.

Gloria

I feel a strong emotional resonance with the cultural history of plants. As a landscape architect, plants come with the job. As a Chinese American, I like to connect the Chinese food and drinks I consume with their plants of origin. It took me some period of time, for example, to realize that Ginkgo biloba, a common street tree in New York City, is the same as 銀杏, a common ingredient in Chinese soup and dishes.

Wikipedia and botanic books in English state that ginkgo was first “discovered” and named in 1771 by Carl Von Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist who invented botanical nomenclature. (When William Prince Jr. decided to rebrand Prince’s Nursery, he named it Linnean Botanical Garden, after the botanist.) Since the gingko is considered sacred in Buddhism, the trees are planted in gardens and temples throughout China and Japan. A German doctor brought the first ginkgo tree to Europe in 1712. A tree that originated in China and has been seen in fossil records dating back over 290 million years ago was discovered by a European.

At William Prince’s house were two ginkgo trees, claimed to be some of the oldest in the country. Other nurseries started appearing near Prince’s Nursery—Bloodgood Nursery specialized in maple trees including Japanese maples, and Parsons Nursery largely introduced plants from East Asia.

As I read more about Linnaeus and the nurseries in Flushing, an undercurrent of uneasiness grows within me. In his treatise Systema Naturae, Linnaeus categorized humans into four racial subspecies, deeming the European race to be superior. The cold scientific language of botanical taxonomy and the extractive nature of taking what is native to Asia to cultivate in the Americas and Europe reminds me of immigration and indentured servitude. Whether to seek better economic opportunities or because of forced labor, these movements are linked directly with colonization and its aftermath. I think about the dishes and medicine from our culture that we absorb in the United States, created with ingredients from the fruits and flowers of our native plants cultivated on foreign lands.

Daphne

In the 1966 Landmarks Preservation Commission memo on the Weeping Beech Tree, the writer notes, “It is unfortunate that no one has immortalized ‘The Weeping Beech’ tree in American literature as Longfellow did the ‘Village Chestnut Tree,’ but to local citizens and to many thousands from far and wide, the Weeping Beech is known, admired, and venerated as a mighty tree, a survivor of a past era.”

I’ve never thought of plants as survivors, but of course they are. They shift their leaves to chase the sun, they’re somehow able to develop root systems in the hardscapes of places like New York City. They find a way to live and grow in spite of the drastic changes to their landscape.

Standing near the current Weeping Beech, I think of the literal meaning of weeping: to shed tears, to show great emotion. The branches and the leaves point downward, bowing to the earth, and form a veil that only lets in speckles of sunlight. Behind the veil, time is less clear. If plants are able to bear witness, I think of what this tree and its predecessor have seen over the past 176 years. The streets and roads that were built, the new buildings, and the people that have come and left. Weeping Beech trees can live for two or even three hundred years. I think of the future and all the different things this tree might see.

The only other living landmark in New York City is the Magnolia Grandiflora tree in Bed-Stuy. It’s been a witness to the neighborhood for the past 138 years. It’s seen development, disinvestment, white flight, Black community development, gentrification, and displacement. If trees can talk to each other, I would love to listen in on a conversation between Weeping and Magnolia and all the stories they would share.

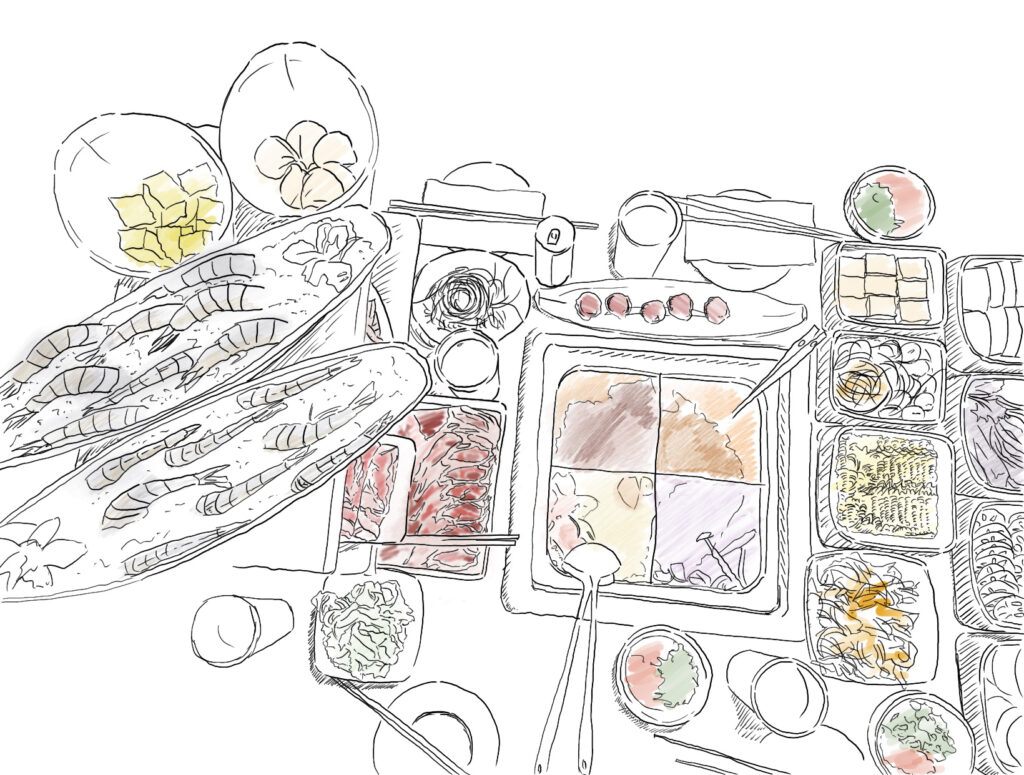

On a crisp September night, we and two friends have hotpot at Haidilao in Flushing Commons. Surrounded by laughter and hotpot steam, we talk about cooking traditions and common ingredients shared among our respective ancestral lands in Jamaica, Haiti, and Hong Kong.

As we step into the large desolate parking lot after dinner, one of our friends remarks on the changes in the land we are standing on and wonders what was here before. Thinking about that, we pause in the streets that are abuzz with dance songs. In the plaza outside the restaurant, seniors joyfully sway to the music.