So much of art is speaking, but art can only be made by listening to the world around us, forming our own distinctive definitions of that world in tandem with what we learn and who we choose to look for.

May 1, 2023

This piece is part of the Love Letters notebook, which features art by Ali El-Chaer.

When I started thinking about a visual artist to work with on the Love Letters folio, I wanted, in my heart of hearts, to find someone who was willing to dream with me. I found that in Ali El-Chaer, a Palestinian artist based in Nashville, Tennessee. During our time together on this folio, Ali and I met three times over call and exchanged about a hundred emails, which opened abruptly (Yi, Ahhhhhh!!!), cryptically (Let’s remove the tiger), and excitedly (I LOVE THE FIRST LANDING PAGE IMAGE!!! -Yi). The forces that propelled our collaborative process forward were our interest in listening to one another and the stories that Ali was so intentionally and thoughtfully bringing to life. Over the course of our time together, they made more than a dozen collages that directly engage with and accompany the twelve stories that make up this folio. Their work is both intuitive and researched. Throughout the folio, Ali remains interested in negotiating the cultural context that the stories’ characters come from, finding symbols that would reveal a story to the audience of those contexts, and selectively allowing their art to be accessed by our readers (you).

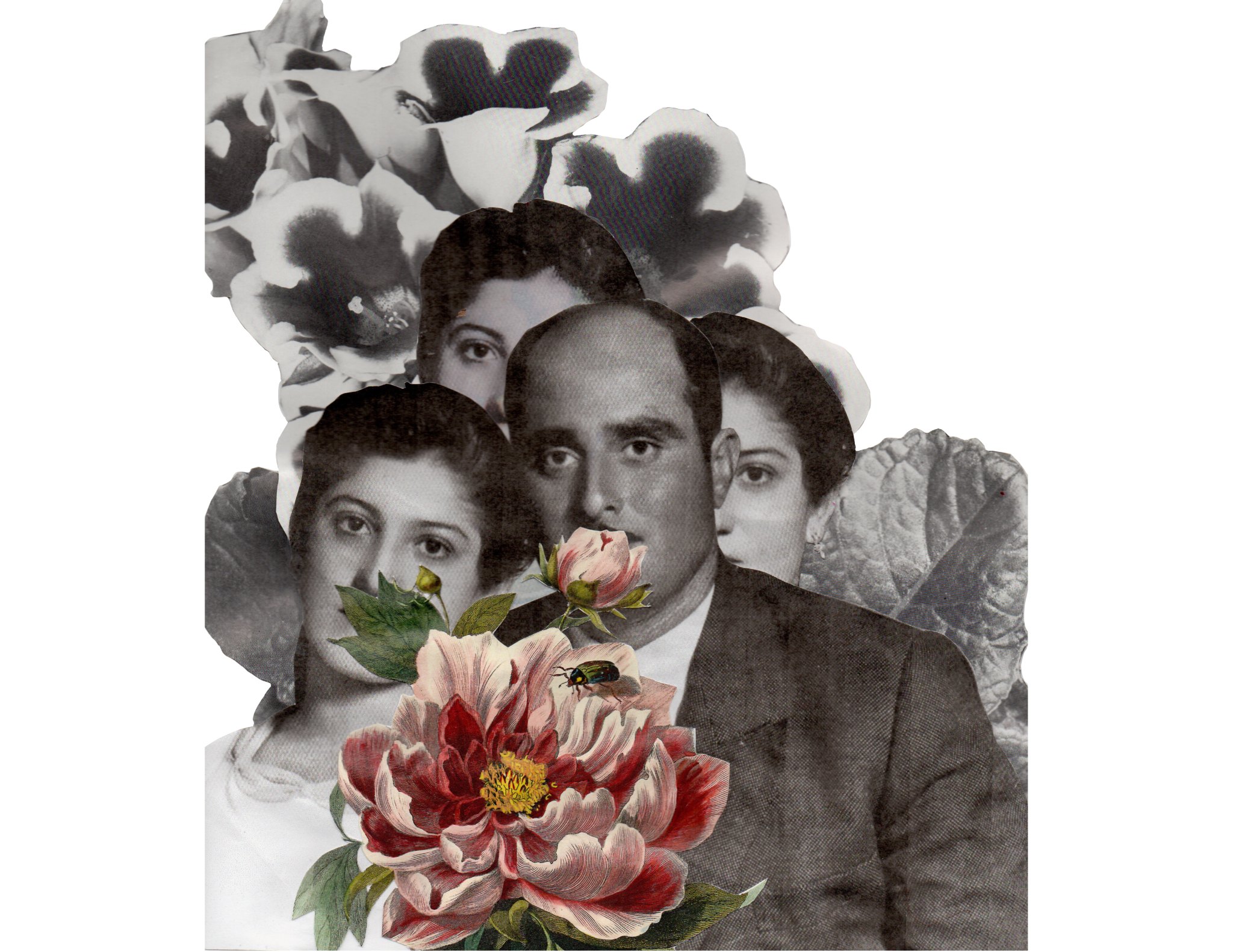

There is an important intimacy at play here that I especially appreciate in the practice of Ali’s art-making. So much of art is speaking, but art can only be made by listening to the world around us, forming our own distinctive definitions of that world in tandem with what we learn and who we choose to look for. You see this in the piece above, “Familial Piety,” which depicts Ali’s grandparents, with their tayta repeated three times in a triangle. On this piece, Ali says, “I made the work because it was one that continues to go full circle, showing all these little details of life. How we are constantly weaving in and out of each other and what a cup needs for us to be filled with joy. I am terrified of losing my last name and desperately want it passed down to my children if I ever have any.” As they express in our interview below, their tayta, especially her flowers and stories, are an important part of their visual lineage.

Ali El-Chaer (they/he) is a Palestinian artist based in Nashville, Tennessee. Their work focuses on colonization, land back, and conversations with the past as a means to improve the future.

علي الشاعر (هو/هم) فنان فلسطيني من ناشفيل. فنه عن الاستعمار، إرادة الأراضي لشعبها،و يتكلم عن الماضي ليحسن المستقبل

Yi Wei (YW)

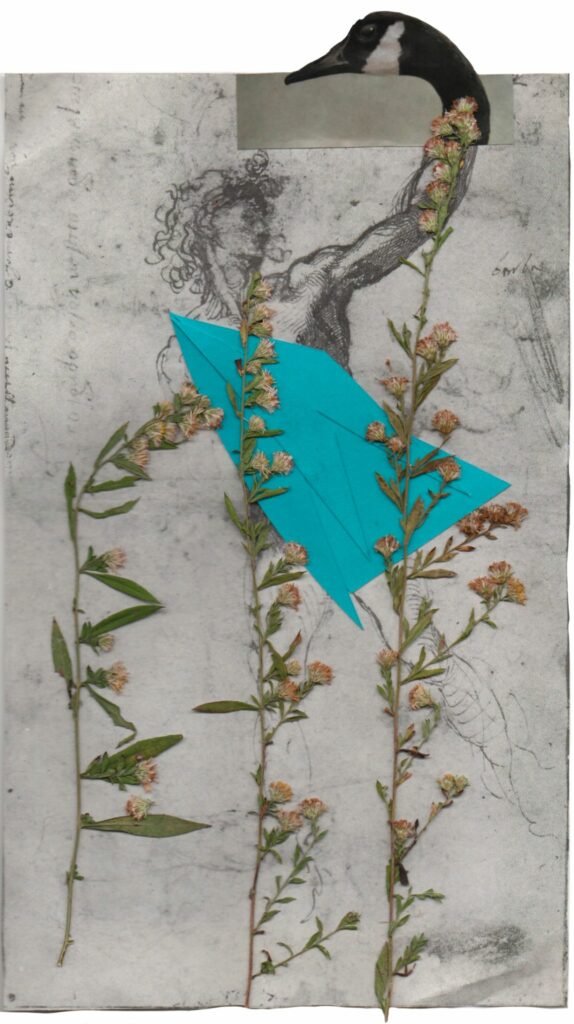

We saved making the image that appears on the folio’s landing page (below) for last because each of the story images in the folio informed that final image. To start us off, I’d love to hear more about the myth-making and symbolism in that work.

Ali El-Chaer (AEC)

The landing image is based on Pollux, one of the twin sons from the Greek myth of Leda and the swan. His brother, Castor, was mortal, whereas Pollux was the son of Zeus. In the myth, Leda was raped by Zeus, who became a swan. I was interested in this myth for the landing page because of the language around it, most commonly the argument that Zeus’s rape of Leda was a mistranslation. The argument makes the case that Leda was dissatisfied in her marriage, excusing Zeus’s actions as an act of love. This gross misdefinition of Zeus’s rape made me think about how other forces have always attempted to re-language or define love for us as something coated in violence.

Love must be defined on the individual’s terms. We may ask if Leda loved one of the twins more or if she loved her husband at all, but by doing so, we burden Leda with our own cultures, experiences, and rigid ideas of how we should be present for others. I wanted to choose a myth that was intergenerationally tragic, like some of the folio’s stories, but posed a greater question of how often we decide for others what love is legitimate, how love (familial in this context) can come at a great loss for the individual. What is required of us to stop the cycle of generational abuse in our relationships with one another? I come from a large family where any sort of relationship can be re-melded to fit someone else’s experience, to the point of denying someone’s wrongdoing. In the end, Pollux asks Zeus to share his immortality with his brother, and they transform into the constellation of Gemini. I chose the myth for how well Leda loved one son to beg his twin to stay with him forever.

Lastly, the dried flowers are called “Robin’s Plantain,” and they grow everywhere in Tennessee. I chose them to dry because they are a natural Band-Aid. I often go hiking; when I scratch my leg and can’t stop the bleeding on the trail, I take this flower, chew it, and put it on the spot to help stop the bleeding. I wish I could do the same when love has hit me so hard, I have no more air in me.

YW

You say that a key part of your creation practice is listening closely. Can you tell me more about this? How does it inform your approach to your work, your audience (or how you consider audience as you make), and your collaborative projects (like this one)?

AEC

Listening closely means a few things to me and how I create: first, I have to actually listen/read thoughtfully multiple times and really allow whatever comes up to come up; I never want to listen just for the sake of responding. In the instance of the folio, there were stories from cultures I am not part of, which required me to listen to it on a human level, then a cultural level. For each work, I researched the backgrounds of the cultures, the possible meanings of colors, and iconography. For a few stories, you and I also asked the writers if they had specific iconography or photo clips they’d want me to work with.

I was not so concerned about the audience outside of the cultures I was trying to understand. Really when making these, I considered myself a guest in the writer’s home. If the writer or someone from the cultural backdrop of the stories saw me acting a fool, I would be painfully embarrassed. In the way you probably wait to see what your host does before eating, I tried to listen to the story and follow its lead.

YW

What drew you to this folio? What is your own conception and/or practice of love?

AEC

I was drawn to this folio because I was interested in all the ways people could take this prompt. There is no exact right way to express admiration or love for another person, experience, or object. The folio took love out of the western lens and placed it with people I could see myself in, no matter how different our cultures. I could see love functioning in a more delicate framework. My practice of love comes from community building and learning. I don’t believe I could love without knowing someone’s history as far back as history could take us.

YW

You operate in multiple mediums and have had both digital and live exhibitions. How does medium, color, and canvas factor into what you’re choosing to depict? Do you find yourself drawn to specific mediums depending on setting or intent?

AEC

When I started showing work professionally, I was exclusively a collage artist. I then moved to different media due to the COVID lockdowns. It was the first time in my practice that I had time to explore my work with the freedom of time and with all the restrictions of money. I came back to collage recently because it lends to my humor in a way canvas never could. I love making jokes in my work as often as I can. For the folio, I chose to work with collage because it is impossible for me to imagine love without laughter.

If I am choosing to paint, it is often because I am having quick, intense emotions I just need to throw out there. My colors in paintings come down to two things: what colors mean in a cultural context and what colors I can find in the trash (my practice is almost entirely found material). I am less interested in material as I am themes. I could read and respond to what I find forever. I have countless works about mythology in the Mediterranean; stories are how I find home in displacement.

YW

Who are the artists and/or the works of art that continue to inspire and inform you? Who would you name as a part of your lineage?

AEC

The Palestinian Poster Project, vintage advertising, and archives of ancient jewelry continue to inform my work aesthetically. I would love to name my tayta Hanne (Allah Yerhama), who passed during this project, as part of my lineage and my artistic practice; her stories and symbols have taken a centerpiece in a lot of my work—particularly the flowers.

YW

What questions are you left with at the end of this folio that you want to continue to explore or move with beyond it?

AEC

How can we continue to love and connect with each other through cultural exchange, migration, and distance? How have we been torn apart from trading and language due to western interventions that breed discord and isolation?