He had once asked his mother to describe his father’s face, a question whose weight he did not recognise until he had been older.

September 6, 2023

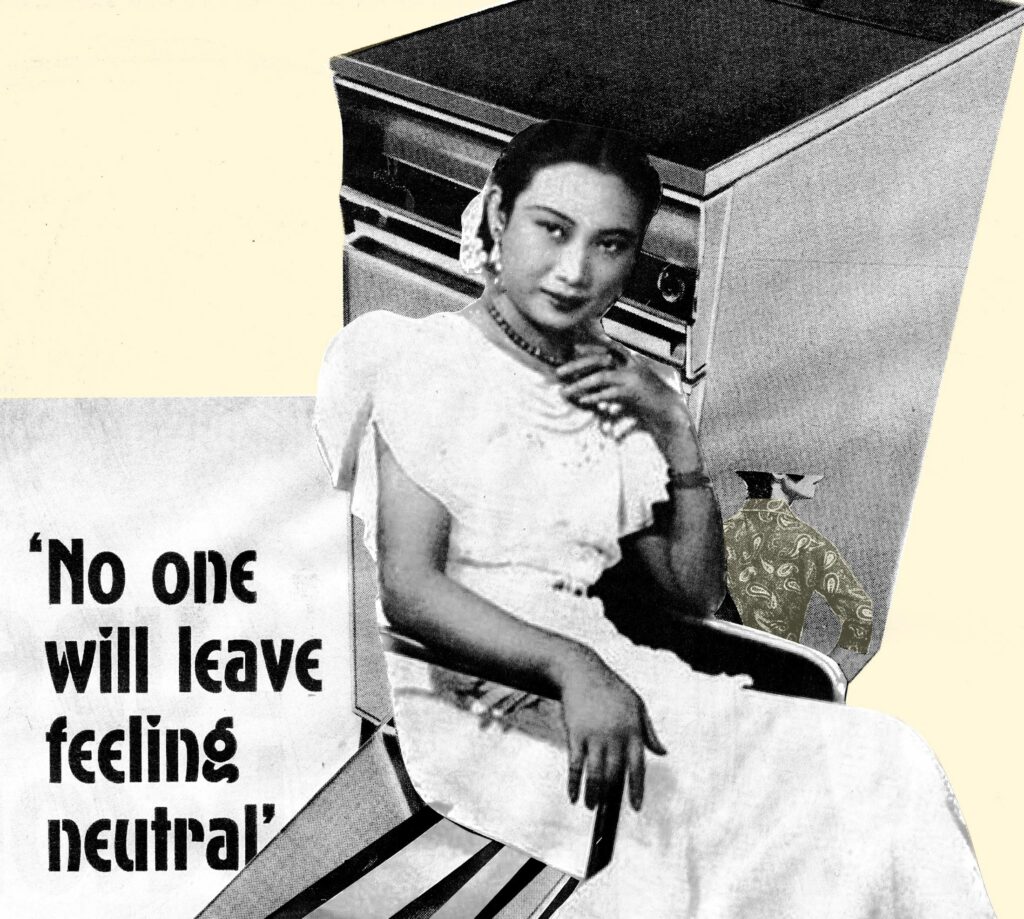

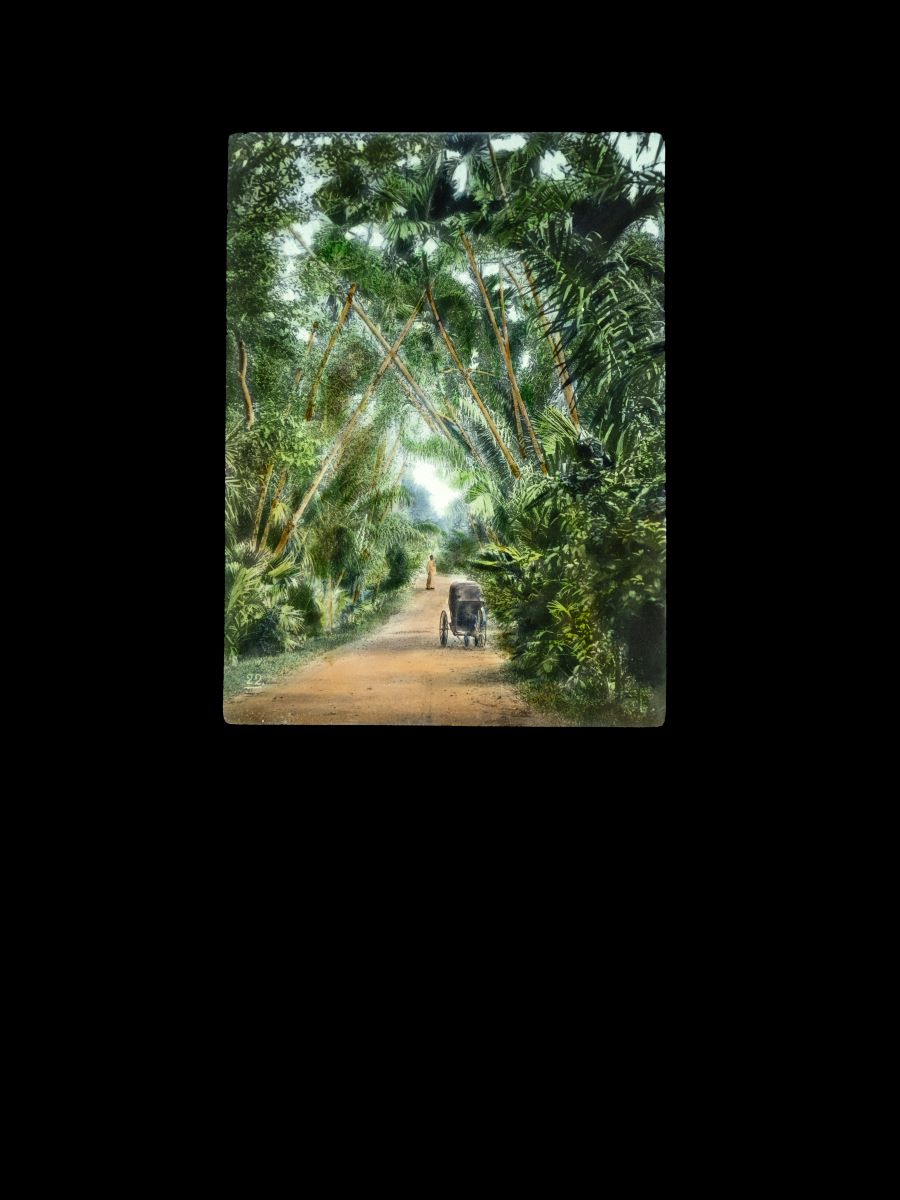

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

He watches the flag go up slowly, uncurling against the morning sun with the sound of the anthem behind it, unfurling itself into the thick heat, the sunlight through the white strips of fabric blinding, delirious. He watches the two students in front of him knock their hands against each other’s, watches two other students ahead of them stifle their laughter. His own belly curdles with his morning breakfast; he tastes ginger at the back of his throat from his teh halia. Then the air changes, quite suddenly, goes thick and heavy and there is a cool whip to the wind, and there is an expectant murmur, the anthem swells—but the moment passes. The heat seeps back into the day.

This weekend, he will have to go back to the plantation. It has been a month since his return, and there is shopping to be done on Friday evening. He makes his list between his classes—some ghee, a new paraffin lamp. Rice and dried fish. His students swarm in and out, and the heat thickens further until it is in the full swelter of afternoon. But he makes sure they pay attention. Not out of force, not by swinging the wooden ruler against the blackboard like some of his colleagues. He is not jovial like some of the other teachers, the ones who joke and rush around full of merriment, almost students themselves. No, that does not come to him naturally—instead his voice is quiet, so that the students have to almost strain to listen. He speaks deliberately, not out of affect but because English is not his first language, because he knows it also isn’t theirs. He focuses on finding words precise enough to capture their slippery history. In 1786, the British obtained the island of Penang from the Sultanate of Kedah . . . this was formal language, not his own. The classroom hot, his ankles sometimes itchy. But always a sense of duty in the room. A quiet that among thirty teenagers was almost magical, impossible.

In the evenings, he returns to the teacher’s hostel, to the flat he shares with three other men. Two of them, the sons of miners from the country, teach mathematics. A Malay-language teacher from Kedah. Each week, they gather for cigarettes and drinks and laugh into the deep night over the antics of their childhoods. Beyond them a fringe of hills, the limestone forests, blacker than the night itself.

He is from all the way south. A plantation estate in Johor. In the mornings, before the sun rises, he goes for a jog—when the air is still cool with the promise of the day, the morning softened by dew and the last damp of the night. It has been a long time since he had performed the work of his youth. But his shoulders, his arms, are still wiry with muscle, the labour that had shaped him, the labour performed by his mother, his father, their mothers, their fathers, the fathers of those fathers, the mothers of those mothers. A line of descent going back to Tamil Nadu, a ship across the Bay of Bengal carrying song fragments that would accompany them to the foreign country that now was his country, whose songs were now his songs. Standing in front of his class, his voice quiet and low: in 1957, on a football field—can you all imagine it? It was midnight. Everybody wanted to be there. The place was full. They lowered the Union Jack for the last time.

Now he closes his notebook, the ink of his ballpoint pen smudged against the flesh of his palm. He checks his pocket again, pulls out a crumpled chewing gum wrapper, two paper clips, the train ticket that will take him south.

The night before he leaves, he dreams of the river. They bathed there, caught fish there. In between the gloom of the palm trees, their endless rows, their mathematical precision. A disorder of silt and light. In his dream he is doing nothing. Yet, it is night, and he is sitting at the edge of the river, his ankles in its water. The air is potent. It is as if he is back already, its weight on his shoulders. It was at the river, his mother had once told him, that your father and I first met. His family was new to the plantation; moved from somewhere else. We were still young then. Still children. He has never seen his father, who had died when he was still in his mother’s womb. There are no photographs, no portraits. He had once asked his mother to describe his father’s face, a question whose weight he did not recognise until he had been older, in love for the first time, looking into the eyes of the girl in his arms. His mother had shaken her head, pursed her lips. Do not evoke him, she had said. He is already free.

But in this dream, there is a shadow between the trees across the river. The heart of his dream self tightens, he feels it rising in his throat. He pushes himself up from the riverbank, squints into the darkness. He blinks—he remembers this motion very precisely, but when he opens his eyes again, it is to the ceiling fan of his hostel room creaking above him.

His housemate, Cheong, drives him to the train station the next morning. There had been a storm the previous night. When he awoke, his body was cold, wrapped in the fog of the leftover rain. The elephant-ear plants outside their hostel with their broad leaves, the speckled dust on their leathery hides, slick with rainwater. Everything smelling of ripe earth.

There is soulful crooning on the radio and Cheong is telling him about the woman from Ipoh he is now seeing; they had met at a pasar, she was buying chrysanthemums. Cheong’s engagement ring glints at him from the wheel and he shifts, the car moving along with the slow traffic, the jungled hills in the distance luminescent with this recent rain. Cheong’s two lovers: this woman in Ipoh, and his fiancée who was waiting back in the mangrove-side kampung he had grown up in—when Cheong first arrived, he had refused to eat fish for an entire week. But what to do, Cheong was saying now, I also still love her, what. Alamak, all this drama—better I run to Singapore, I tell you. Start again.

Later, he bids goodbye to Cheong, who helps him unload his luggage, tells him to get him on payphone when he returns, so that he can drive him back to the hostel. Don’t go and waste your time taking teksi ah. He arrives on the platform amidst the screech of wheels, the plumes of exhaust. Already there is grit on his lips. He licks it off. His raffia bags carrying the tins of food, a sack of rice. He settles on a bench while he waits, pulls out the textbook that he always carries with him. What meaning can he derive from those clunky paragraphs, the amateurish illustrations that make him ache. Someone had sat down and drawn these, almost childish in their simplicity: movements are stiff and without grace, the faces are crude. And yet, there is clear effort in the rendering: the delicate, earnest colouring, catching shadow and light. The history that he teaches is simple. Once there was this land and its tradition. And then the Portuguese came. And then the British. And then the Japanese. And then the British again. And then we were free.

It is night by the time he arrives in Johor. The hills running down the spine of the peninsula soaking up the blue of the evening. The smell through the open window was fresh air, some exhaust, the stain of lemongrass rising from the bag of one of the other passengers. When he gets off on the platform, there is a light rain, almost invisible but beneath the cradle of a streetlamp’s flare, he feels it on his face when he looks up. Then, he heaves his things onto his shoulders and heads down the platform, walking out into the depth of the night.

In the morning, he awakes on the floor of his house in the plantation. The sunlight is bright and hard against his skin. For a moment he is confused—does not recall how he had arrived home the night previous. The walls of pink clay around him, the tight room. The things he has bought from Ipoh seem larger now that they are in the house. He stands and stretches, walks outside beneath the sun with a towel slung around his shoulders, his dhoti—which he has never worn in Ipoh—slung around his hips. Almost everyone is at work already—somewhere out in the plantation lines. Including, and his heart clenches at this, his mother. But he grinds the thought down: a few more months at the school and then he will make enough to find them a small flat on the outskirts of town, he can bring her over, away from this life.

He makes his way down the laterite road, the houses around him quiet. He knows that the ingredients he has brought will, that night, be made into a feast. That the estate has waited for his coming for a long time, knowing what he will bring for them.

But there is one person still left in the estate who has not gone out today to the plantation. It is the old man, Aruvalam, toothless now, his face a series of collapsing furrows. He watches the old man’s eyes widen, watches him move his mouth. Aruvalam, who during the war had been taken by the Japanese, brought to Burma to work on the death railway. Aruvalam, who had been thought dead but returned one day quite simply, as if it had not been years between his disappearance and reappearance, his capture and his release. Aruvalam, who now calls out a name but it is not his name, it is his father’s name, and this stops him also so that he stands in his tracks, his shadow falling on the heat-baked road ahead of him, and he looks at Aruvalam and Aruvalam looks at him, and then he repeats the name once more, and then once more again, thrice, as if sealing a spell.

Sure enough, that evening the women begin preparing the feast. The men draw around singing their songs, and the smell of fry rises, hangs over the estate, the houses. The snapping fire and the char-smoke and the children with their laughter.

That evening when his mother had come home, he had greeted her. He had cut up some bitter gourd for her first, fried them already, so that they had something to eat before the feast, and they sat on the earth floor together and spoke.

“How are things in Ipoh?”

“Everything is good.”

“And the boys you stay with? In the hostel?”

“We are good to each other.”

“And the students?”

He had shown her the textbook, knowing that she could not read in either Tamil or Malay or English, but her finger had traced over the words, her eyes squinting at them, as though she could. He had not spoken to her of the intricacies of the history there—what they had said, what they had not said.

“Your father,” she had begun, but then she stopped. He took the book away from her and closed it, and they both rose to prepare for the feast ahead.

The night grows loud and raucous, there is singing and toddy. He declines the drink, his neck already damp with the heat, with the spice of the food. The songs are long and without end, and he too dances, stepping in and out of the ring of light cast by the flame. The songs of his childhood, repeated in his youth, and now in his adulthood. No child of his will sing these songs. No child of his will have to hear the lullaby of his own childhood. I boarded a ship—time eradicates. I never returned. Two trees—tall trees—suitable as a gallow tree. None of this. Once, with the rest of his housemates, he sang the songs of their childhood into the night. All the songs that their mothers had sung to them about lovers left behind, or homelands that no longer existed, the folktales in which a boy leaves his village, returns home but turns away from his mother, turns his back on his people, and so is turned to stone.

If you look out into the earth in the dark, a girl he had loved had once told him, the first girl he had loved, from this plantation too—now he looks at her across the haze of the fire, sees her with a baby on her hip—if you look out into the earth in the dark, you can hear it crying.

Now he looks past her, into the dark heart of the crying earth and he thinks he sees something moving in the trees, a pair of eyes, but perhaps it is only the firelight, but still he cannot help it, he cranes his head forward—

He hears his father’s name behind him.

When he turns, it is Aruvalam standing there.

“Uncle.”

A shadow across the old man’s face, and then he speaks again.

“No, I was mistaken. It’s you.”

“It’s me.”

The old man sways, unsteady with drink. He takes him by his elbow and brings them to sit down, both of them cross-legged, a little ways from the gathering.

“Have you eaten, uncle?” He asks.

“I ate well,” Aruvalam replies. “It is thanks to you.”

“How are you, uncle?”

“Listen to me,” Aruvalam says. “There is something I need to tell you. Have you heard the story of your father? I saw him in a dream last night. I thought you were him, but you are not. So I think this is a story you must hear.”

“I know all about my father, uncle. My mother does not keep secrets.”

“Not about his death or why he died.”

“What then, uncle?”

“About the time he followed the tiger.”

He pauses, looks Aruvalam straight in the eyes. Firelight dancing in the dark pupil that was still unobscured by the cloud of cataracts. A bright blue ring around the deep well of black, and the fire dancing within.

“I do not know this story, uncle.”

“Your father was a young man, and your mother had just revealed that she was carrying you. It was a month when the estate was afraid because we had heard of a tiger that had come out of the jungle, made its way to a plantation. We were receiving strange omens. Twelve dead white owls one morning. Seven days of red sky. Strange songs from the river. And then we saw the tiger itself. I remember it. I had never dreamt that it could have been so huge.”

“Where did you see it, uncle?”

“You know where already. You know it in your heart. It was by the river.”

“What did my father do?”

“He walked away from us. We were all shouting, but he was very calm. It was like he was possessed by something, but that was your father. He was a man who carried something inside him that we could not always understand. He slipped into the river. He swam across. We were screaming, shouting. Someone had run to get your mother, had run to get the women. I was on my knees also. I was begging him to come back. But he was already on the other side. And the tiger was waiting for him. He came out of the river—by then, we were sure that we were witnessing the last moments of your father’s life. But instead, he put his hand on the back of the tiger, and they both turned and went into the trees. You know how the line of trees are so straight, that you can see the other side of the world through them. But your father and the tiger disappeared quickly.”

He was listening closely; all the noise of the party had disappeared, and it was only Aruvalam’s voice, raspy with age and drink.

“Your mother came, and she also fell to her knees and started weeping. Why would he do this to me, she was saying. Her hand was on her belly. I will never forgive this man, she was saying.

“We were all there. Hours passed. The sun fell low, and the sky turned yellow. The overseer came. He began shouting at us. He wanted to beat us. But that day, we held him down, we refused his violence. Our grief for your father made us strong enough for that. For a long time, we waited. A deep grief in my heart like I have never known, even the day that the Japanese took me. Even the long years I was with them.

“But then, he returned to us.”

He was looking keenly at Aruvalam now, taking the storyteller in. The wizened muscle of his shoulders, the leathery skin. The silver scars that looped around his arms. The head of white hair that sprung confused from his head. The beautiful, gentle eyes and once-broken nose.

“We simply looked up and saw him, standing alone across the river. Then he slipped in again, swam towards us. He rose on the bank and came to your mother, who was standing now. He bowed down before her, put his head to her feet. Then he rose and embraced her. That was all.”

That whole night, he is itchy with fever. He dreams of the river again, and he is looking into the line of trees and seeing a shadow. He knows what that shadow is but still he cannot parse it; cannot read into it more than mere shape. He goes for an early wash in the river, but it is peaceable. He sees nothing strange. He arrives home to see his mother already preparing for the day.

“I will come to the plantation with you; I want to work.”

“No.”

“Amma.”

“Your work is no longer here. Your work is outside.”

“Please, amma. I want to work. I cannot just sit here.”

“No.”

He watches her light the oil in the new clay lamp he has brought. Her back towards him.

“Amma, Aruvalam uncle told me about the tiger. About appa.”

He watches her straighten up, watches her turn towards him.

“Amma, is that story true?”

For a long time, she does not speak.

“It is a true story,” she finally says, quite simply. Her voice is clean, without weight. “Three months later, they came after your father. You know what happened already. He was working with the Chinese, he was working with unions. You know what they accused him of. They came to tell me this afterwards. They thought it would shame me. They thought I didn’t know. As if that was not why I loved your father. They delivered me his head and thought I would scream, that I would cry, that I would die in front of them. I took it from them as if it were a holy thing. Yes, there was a tiger. Yes, your father followed him. Your father was such a man.”

He does not go into the plantation to work. Instead, he cleans the house, arranges his gifts. No one is left in the estate today, even Aruvalam has gone out to work. He takes a long nap, wakes up into the heat of the afternoon rupturing against his body immediately upon waking. For a moment, he blinks into the swelter of the day, then he stands and makes his way to the river.

There is a weight in the sky today; there is the promise of rain. The air hangs low, it presses down on him. He walks through the line of trees to the river, feels the density of the air, thick with the grease that slips off the palm leaves. The little wooden houses in which the owls lie sleeping. He is walking quickly. He realises this. Until finally, he can see the river ahead of him, that break in the plantation line.

He walks towards it, looking into the other side. Everything is clear in the daytime. In the far distance, he can see the breaks of light that promise the end of the plantation. He stands there, looking into the trees. For how long he stands there, he does not know. Until the sky turns yellow, folding in upon itself. The air is electric, urgent, but no rain comes.

He dreams—he is not aware of settling down on the grass, of falling asleep—of the classroom. The slant of light through the window, the students listening to him. His textbook open in his hands. For a long time, he stares at the text, until it has blurred, until all language dissolves. Then he closes the book.

He dreams—he believes he is still dreaming—that he is awake again, that he is standing in the river, up to his waist in the water. He is looking into the trees, and there is shadow in them, and the shadow is walking out of the trees, is becoming human, he sees the face now, his face now, sees the man in front of him crouch by the river, reach out his hand—he stretches out his own—

When he wakes, he is back on the floor of his home. He can hear his mother breathing, sees the rise and fall of her silhouette. Moonlight through the open window. He closes his eyes and falls into a deep and dreamless sleep.

The next day he bids his mother goodbye in the formal way. He embraces her, then he falls onto his knees in front of her, puts his hands to her feet. He also goes to see Aruvalam before he leaves, thanks the old man, promises to come back soon, to see him again. He does not go to the river; he is for now finished with the river. It has spoken to him already.

Then, he leaves the plantation and is soon on a train back north. He chooses a seat facing the back of the train, so that even as he moves forward he can still see the plantations that they are passing through. He can still see the jungles, can still see the hills. Can still see the country they are leaving, that he has not and will never leave behind.

Translations of the Tamil folk songs quoted in this were derived from the article ‘Maladaptive Behaviour of the Tamil Labourers during British Colonisation as Reflected in Malaysian Tamil Folk Songs‘ by Logeswary Arumugum and Kingston Pal Thamburaj, published in the Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, vol 3 issue 5, 2017.