Transgressing spatial and temporal bounds through the image

September 6, 2023

This piece is part of “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” featuring art by Sim Chi Yin.

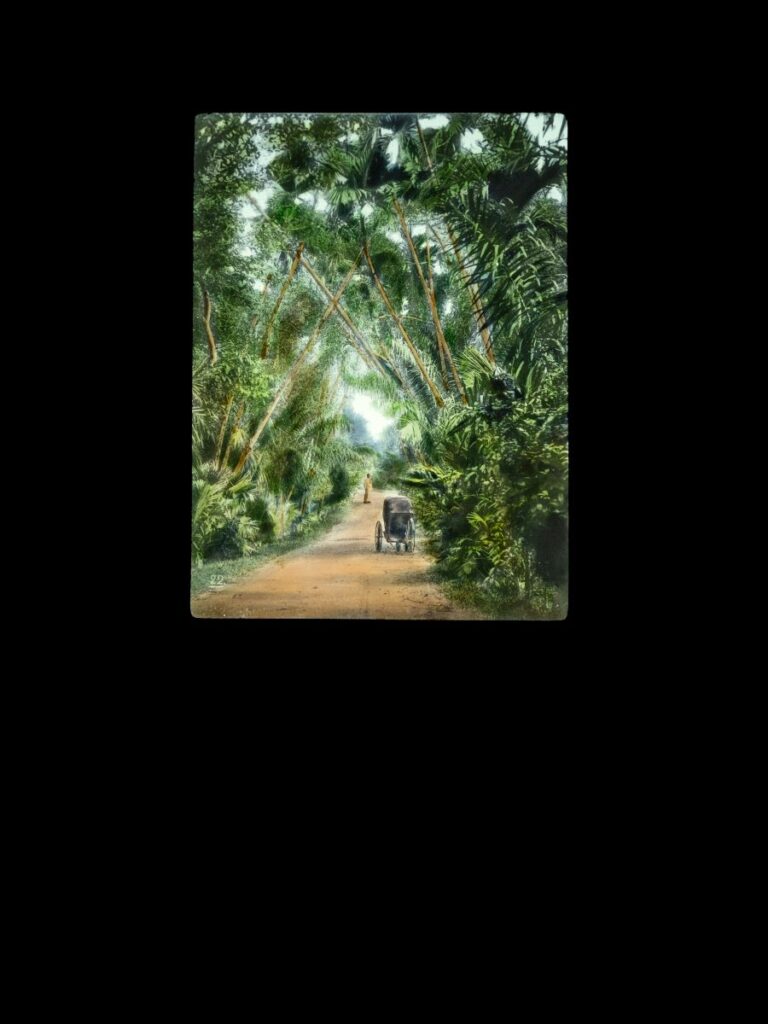

Sim Chi Yin’s 2023 installation The Suitcase Is a Little Bit Rotten consists of a series of glass plates with reappropriated Magic Lantern slides, displayed on replica negative retouching stands updated with lightboxes. They feature familiar scenes from old Malaya, with one slide depicting a crowd of Malays clad in their signature sarongs and velvet caps, watching some spectacle off-frame. Perhaps it is a kampong tamasha, one of those traveling entertainments that once brought romances of China and Hindustan to villages upcountry. Or maybe it’s a firebrand nationalist talking about kicking foreign races out. Another slide centers a young man scaling a coconut palm, the sea behind him placid and unspoiled. But Malaya’s seas were also a place of work—a third scene shows dockworkers, their faces hidden by broad-brimmed hats, unloading harbor tongkangs. The hills suggest Hong Kong, but it could be one of Malaya’s ocean ports, Penang or Singapore.

This installation is part of Sim’s decade-long project “One Day We’ll Understand,” consisting of photographs, moving image, installations, and performances on the Malayan Emergency, an anti-colonial war fought by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) against the British. Following the Second World War, the MCP emerged as the only group organized and popular enough to mount an effective independence movement. Even English-educated Malayan radicals worked with them. But the British had other plans, launching a brutal campaign against the MCP in 1948. Legions of MCP fighters took up arms in Malaya’s jungles.

Sim, an artist, journalist, and photographer from Singapore, was drawn to the Emergency after coming across a photograph of her grandfather—a man suppressed from family memory for sixty years—carrying a box camera. Pursuing more information about his life, Sim found out later that he had been among the many Chinese Malayans who took part in anti-colonial activism. Captured by the British, he was banished to China as part of a punitive mass deportation of Chinese leftists and communist “sympathizers.”

What the British considered repatriation, however, was a painful exile for Chinese Malayans from the only home they knew. It reflected an established view among the British, and later Malay nationalists, of the Chinese as essentially foreign to Malaya. A way of thinking about cultural belonging and geography, dating back to Enlightenment historiography in the late eighteenth century, informed this colonial construction of Chineseness as a racial category bound irrevocably to a national homeland: China, never Malaya or anywhere else. An older tradition of cross-cultural mixing and assimilation in the Malay world, however, predated the nineteenth-century colonial state. Europeans themselves, like other diverse Asian peoples, had intermarried with locals and, to varying degrees, became Malay by cultural adoption.

That colonial tradition, however, of representing Malaya’s culturally complex population as a set of fixed racial types, is captured by Sim in The Suitcase Is a Little Bit Rotten, with its lightboxes resembling specimen cases, each isolated from the other. Under this schema of racial types, each group had a distinct dress and customs, but more importantly, economic function. Malays were genteel, but indolent. Indians were obedient, but sly. The Chinese were hardy and enterprising, but preyed on Malay land and resources. So it was up to the Europeans to balance everyone’s interests, combining their strengths to make the whole system work. Postcards and travelogs, painting the same portraits of a Malaya with inhabitants cast in immutable roles, formed part of this imperial modality.

Of course, like the British magic lantern shows that inspired The Suitcase Is a Little Bit Rotten and were made to teach children about the diversity of the Empire, this taxonomy was always fragile. We see Sim’s grandfather disrupting the classifications that these glass sides represented, by appearing like an apparition in them; he has been inserted, in Western shirt and trousers and camera in hand, behind the Malay crowd. Hovering over the Chinese dockworkers, he looks on from a ship’s railings in a sharp suit and hat.

By grafting images of her grandfather into these lantern slides she collected, Sim toys with the ambiguous uses of photography in Malaya as a tool not just of imperial classification and control, but also of self-formation and self-fashioning. Not long after photography was introduced to Malaya, local rulers began using it to lay claim to “modern” authority. These ruling elites were photographed in royal robes as well as European suits, sitting on ornate chairs. Wealthy merchant families and ordinary townsfolk alike cultivated aspirational visions of themselves in photo studios, as did Chinese dandies and Malay effendis. Kuala Lumpur–born playwright Jo Kukathas called the studio portrait “this very Malaysian of traditions.”

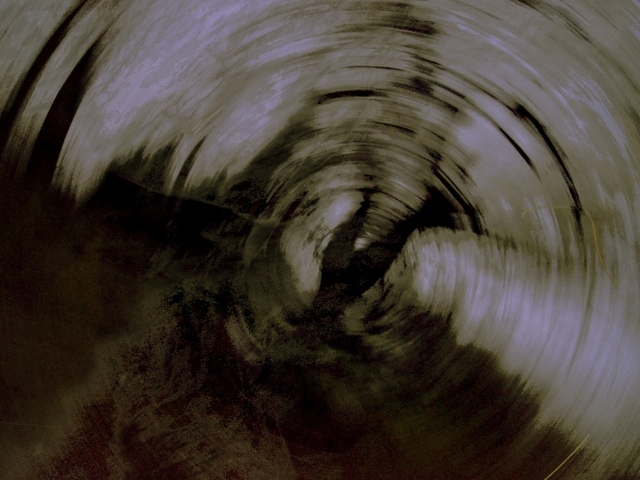

Sim’s photographic “time travel,” as she calls it, joins that Malayan tradition of transgressing spatial and temporal bounds through the image. Her infant son, appearing in one of the slides in The Suitcase Is a Little Bit Rotten, crosses paths with his great-grandfather. In her 2022 lecture-performance at the Asia Art Archive in America, “Methods of Memory—Time Travels in the Archives,” Sim showed photos of her grandfather in happier times—or so the photographs make us believe—at family outings, as a student athlete, and in other settings suggesting youthful ease and energy. Between Sim’s voice and the images, a dialogue takes shape between her and her grandfather, filling in the silence and distance of time that separate them.

Sim’s art denies the triumphalist narration of the Malayan Emergency, in which anti-colonial Chinese communists aren’t automatically assumed to be vanquished “bandits” or “terrorists.” Official accounts in Malaysia continue to cast the MCP fighters as Chinese racial chauvinists, and their defeat as the triumph of Malaya as a Malay race-nation. A well-documented Malay leftist movement existed. Both it and the MCP’s sizable Malay unit, the 10th Regiment, which drew inspiration from earlier local uprisings by Malay chiefs against the British, are deliberately overlooked. By physically removing Chinese MCP fighters, the British and their Malay nationalist allies reinforced the idea of the Chinese as perpetual outsiders to the Malay world: whether as usurpers in Malaysia’s case, or model migrants in Singapore’s.

The ruling regime in Singapore, where Sim is from, still claims to have heroically rescued the island from an MCP takeover through mass detentions without trial of suspected “communist” sympathizers allegedly linked to the MCP. Archival records cast serious doubt over these claims. The shattered “Malayan Dream,” as historian Hong Lysa calls the eventual separation of Singapore from Malaya, looms over Sim’s conversations with her grandfather who fought for a now-divided country.

From the vantage point of Sim’s work, history looks less like a timeline of epochal struggles with a clear end and beginning. The past continues to speak, act, and guide in the present through personal encounters. This may be the counter-method to history as a study of the past from an omniscient vantage point: to be pulled in inexorably by a past, following where it leads, through memory and silence. We may understand the lasting effects of loss and gaps in the records better if we renounce tidy chronologies.