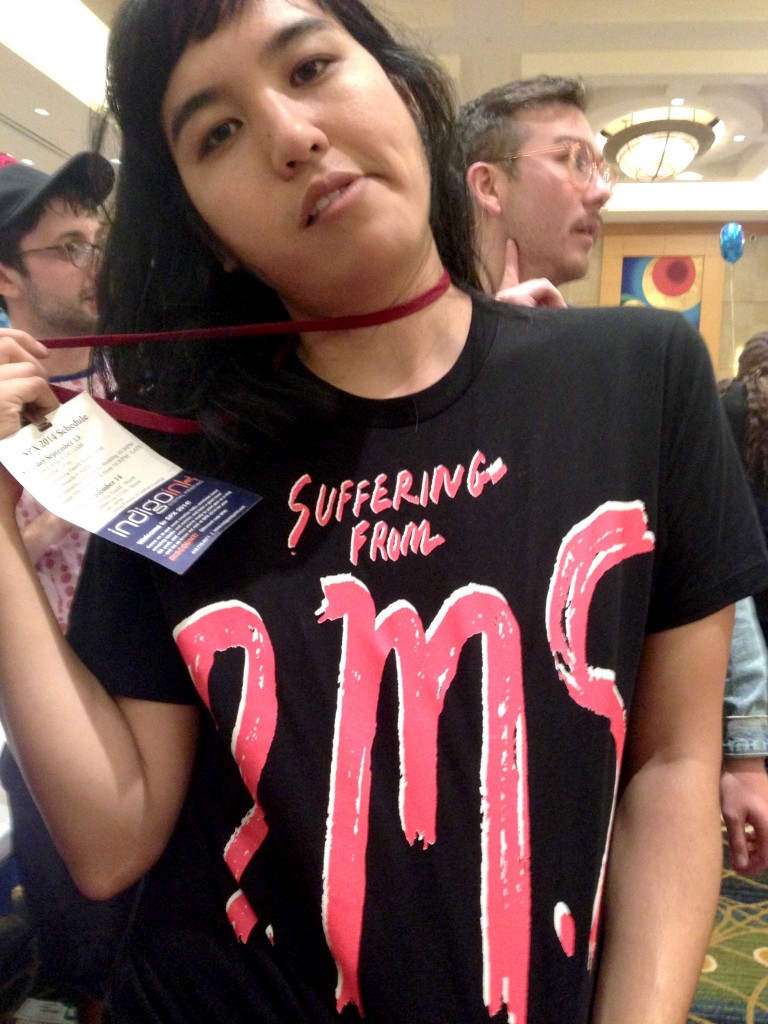

The artist and illustrator of Skim and This One Summer talks about the tension of tween-hood, body types in mainstream comics, and why purple is the warmest color.

October 9, 2014

AAWW board member and resident comics expert Anne Ishii keeps it coming with her new series of conversations with Asian American (and Asian Canadian) comics artists in The Margins. Check back for more.

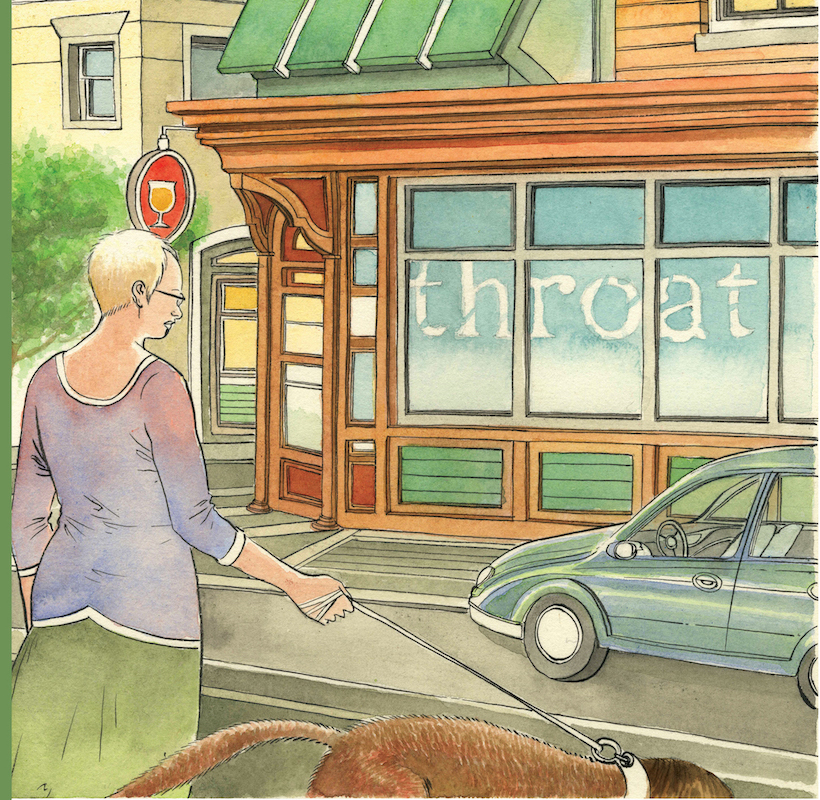

I spoke to Jillian Tamaki in the lobby of the wrong Toronto Marriott. That is to say, the rest of the comics world had converged for the Toronto Comic Arts Festival at the Marriott up the street from where she was staying. It’s an apt metaphor: having this conversation at the lesser known outpost of an industry event because she wanted to be available but wasn’t interested in following rote social patterns.

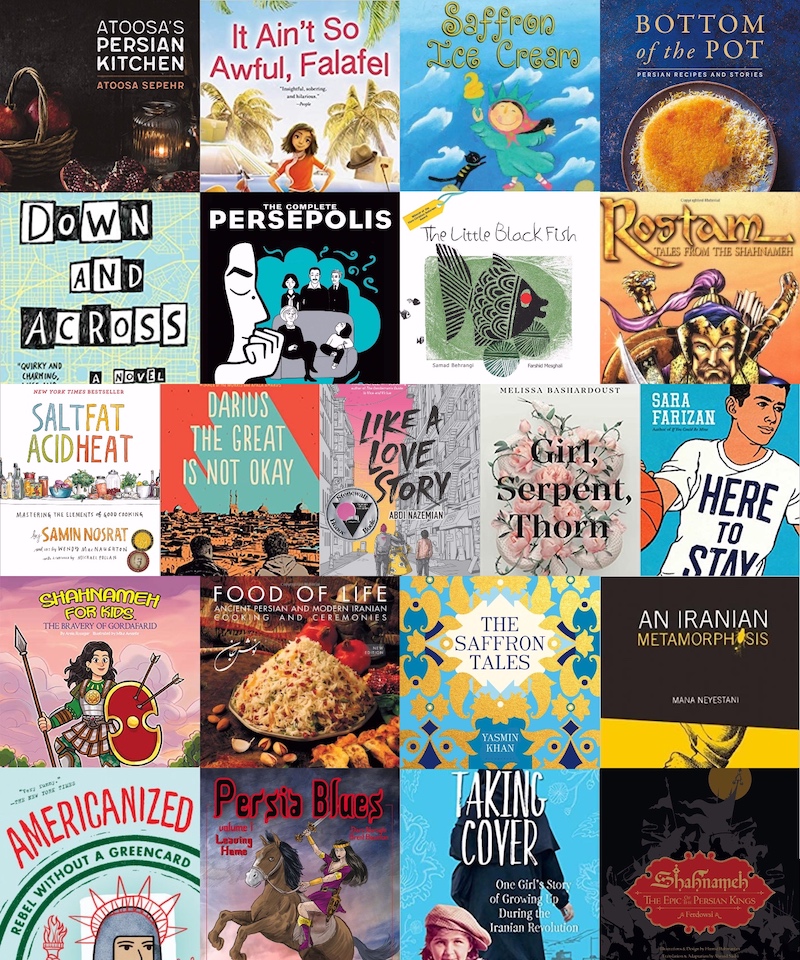

Jillian is the illustrator-half of the graphic novelist dyad behind the critically acclaimed Skim and as of this writing, the unparalleled This One Summer, which debuted in May. The duo includes Jillian’s cousin, writer/performer Mariko Tamaki, who was on other interview duties, leaving me to focus on itinerant issues of depicting identity and the art and craft of developing a persona, on paper and in real life.

After greeting each other in the lobby, Jillian and I moved to a café booth where she noticed I was wearing designer sneakers. I made a point to address that I am not a sneakerhead but happily accept designer gifts as such.

Anne Ishii: Do you consider yourself into streetwear at all? Or are you just a casual person who dabbles in fashion?

Jillian Tamaki: I wouldn’t even dare to say that I dabble. I don’t think I’m very stylish. I just feel like I have, through trial and error, found things that work on my body. That’s as far as I would go.

So what works on your body? What’s your uniform?

Sacks. Shapeless clothing that kind of drapes. (laughter)

You know that label, Eileen Fisher? I’m gonna wear Eileen Fisher when I’m old. That’s my trajectory. I’m sort of just lollygagging around, doing variations on that, but I will distill to Eileen Fisher.

I am more into amorphous clothing. Today I took a double XL sweatshirt and turned it into a kid-sister dress.

But there is something kind of weird about obscuring your form. It feels a little bit subversive, which is funny because I remember when I bought my first pair of really tight jeans, almost 10 years ago. That felt explicitly sexual and super freaky. And now that everyone wears that all the time… maybe I’m just older… it feels really subversive to wear things that purposefully obscure your form.

Is obscuring your form, you think, more subversive than sexualized clothing?

I feel like saying “fuck you” to sexualization is pretty subversive.

I mean the first thing I think of when I hear “subversive obscurity” is the hijab.

Women’s bodies are like public property. And to actually shield that makes people fucking mad, you know? So I think there is something to it.

I’ve never liked people looking at me. I didn’t have a wedding—and it was mostly because we weren’t in the situation to have one—but that’s my nightmare: everyone looking at you with expectation.

Then, how do you deal with visibility in the virtual sense now that you’re so acclaimed as an artist and illustrator?

I feel like that visibility is an illusion and it’s easier to exert control over it. I don’t know. Maybe it isn’t easier. I guess I’ve never been totally trusting. I used to be really reluctant to put any picture of myself online because as a woman you are always going to be judged, but I did this thing where I Googled my favorite comics art authors and there were always pictures of them in the first search result. But if you did that for a man, there would generally be fewer pictures. I don’t want that to be part of that conversation (about body image), but it’s just impossible to avoid.

There’s an interesting spectrum of female body types in This One Summer. Some of it is really subtle but you even get this sort of genealogy of body types, like between mother and daughter and then phenotypes, like the Native American woman.

Visibility is powerful. And if you make one of your characters adopted, just the visibility of that aspect shows how this is a person that exists in the world and that her whole story isn’t just one thing. You’re not defined by such narrow facts. Also, you can kind of incorporate different body types in narrative tropes—the character Rose and her mom are supposed to look really similar because the mom is the future version of the kid. But the little girl who’s adopted looks totally different from the mom, who looks totally different from the grandma. They all look totally different. I think there is some narrative stuff that comes into it. But again I feel like there is not a diversity of women’s bodies in the comics world.

Would you say that it is a real problem in comics art?

I think it’s becoming less so. I teach at SVA and I see the comics made by the girls I teach. I am exposed to really smart girls that feel the need to make really inclusive comics, so I see all the time that people are really interested in this. I see that there are people making it. But I guess even on the grander scheme in mainstream comics, which I have no interest in, things are definitely getting better. Do you think so?

I do but it’s funny that you preface that with the caveat that you don’t care about mainstream comics, because that is where the most mediatized problem is and presumably still represents the lion’s share of comics fans.

Right. I think I just have no context for them and so I can’t comment on it. I personally just think that they seem interested in the sort of stories that wouldn’t appeal to me so why should I care about them?

I don’t think it’s anybody’s responsibility to create universal appeal, but I wonder if part of this divide might even subconsciously have to do with the fact that mainstream comics are an American macho phenomenon and you come from a Canadian context. Is that maybe even a completely different race of comics? I wonder if there’s any nationality to that machismo?

I think we Canadians always move toward America, although there are still some fundamental differences. But I don’t think it’s so much of a virtue to be super powerful and dominating here. The idea of saving the world is not in the Canadian psyche in the deeper way that it maybe is in America. There is an element of the American dream in the Canadian psyche. It’s like, you can move here and make a future for yourself, but I don’t think Canadians traditionally have been the most macho society (laughter). It is just so funny that the great cartoonists of Canada have built their reputations on being a kind of specific sort of guy. A guy to be sure. That is something that I’m off about. It is interesting and I don’t know why.

In terms of depicting bodies in This One Summer, even the way you depicted masculinity is interesting. There are prototypes, but they’re complicated. Rose has a crush on this guy, Dunc. And surely puppy love (for older boy of questionable character) is a real experience for most girls. Where did that story line come from? Because she’s so vulnerable and you get so scared for her…

I think the whole book is about tension. Tension between two friends, tension between different age groups, sexes, husbands, growing up and being a kid; between Summertime and real life. It’s all about this tension point. And I know that Mariko will say that it was somewhat based on personal experience—you know, being obsessed with the teenagers, understanding that it’s what comes next. But from my point of view, I was thinking about how to create this boy that was not just a stand-in for exposition. He’s kind of that teenager that if you look at him at a certain angle, he’s handsome and from another angle he’s totally gross, pimply and disgusting. And I think that to him, the interactions with Rose are nothing. He has no awareness of the turmoil that is happening in this little kid, you know, she’s just a little kid. At that point, he’s already left childhood behind and can’t really empathize with Rose. I think that’s the tension point between childhood and being a teenager.

That tiny little jump—between pre-teen and teen—feels so gigantic when you’re that age. I find that people are either sentimental about their childhood or loathsome about it. Do you feel one way or the other?

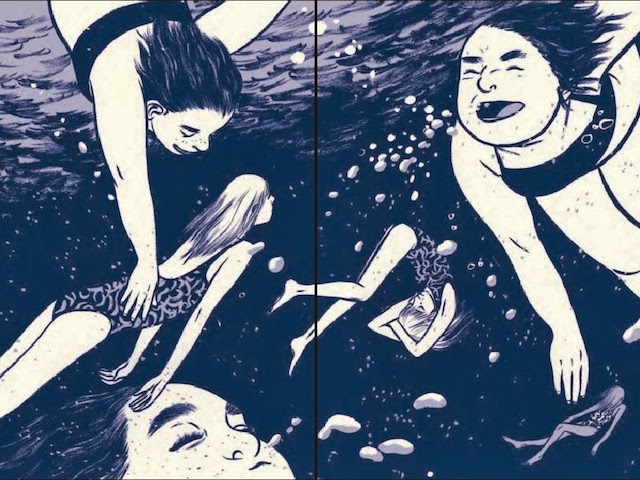

I kept diaries as a teenager. And then when I was 24 or 25 and I was moving down to New York and getting rid of a lot of stuff, I just threw them all away. At the time I thought, this is super embarrassing and I would never want to read this, this is humiliating. Now I’m like, that was really dumb. So I think that your viewpoint evolves as you get older. A) I probably could have made a book out of that stupid stuff, and B) it’s such a harsh judgment! It’s you but it’s also a 14 year old. I think that kids now have a heightened sense of nostalgia and that’s what I was trying to do with the book. Rose notices nostalgia in the making—nostalgia is being created through these experiences. Even through the mini flashbacks and echoes, Rose already knows about nostalgia. She’s aware of the melancholy of change. And that’s why I think the use of the purple across the book adds to that in some sort of slight way. I used it because I thought it was cool, from vintage manga, but it does do something—it tinges it less directly than sepia.

What’s the color psychology there? You just said that the purple harkens back to vintage manga.

Not in any symbolic way. I mean, Rose reads manga and she is a manga fan because she’s like… 12. But I just thought it made the book feel a little warmer. Plus it looked different and unusual. Just on a formal level, it adds something undefinable—something nostalgic and a little bit warm.

I’m struck by the idea that purple is a warmer color, because for me purple is a really cold color.

I think it depends on the purple. It’s not a color you really see in nature, but it’s one that I do associate with fantasy. Whenever I would play videogames and there was some sort of fantastic element that would pop up on the screen, it would be in purple. I don’t think it’s a color that has strong associations like green or sepia or red.

That would have been an intense book if it were in red.

Oh my god, that would be a completely different thing, right? And certain comics would be great in red.

Another element that I want to ask about are the emotional landscapes in which you create full sensorial spreads. Was there a cue from Mariko there? Or is that how you interpreted something that she had written?

I like to think that I’m always guided by what is on the written page, and then I like to add to it if I think that it needs heightening. Mariko does give some slight art direction, but it’s rarely specific. But the emotional landscape is a nice break from events and exposition. Some of it is just like, we need a breather here. Something to kind of rest on when they are underwater.

Well that’s the irony because it is a breather, but Rose is always her holding her breath under water. It’s really fascinating.

I did think about that with the spread of just clouds. A lot of the book is an exercise in describing a place through your senses. We went to Muskoka, which is where Rose spent her summers. I’d never been before, and I mean, how much can you learn from just Googling a place, right? Nobody is going to take a picture of the garbage cans, you know what I mean? But I wanted to convey the overflowing garbage cans.

Speaking of which, another sense that you are trying to communicate is smell. Conveying breath is so unusual and you’ve been able to do it so well.

It’s funny because I think that comes a lot from Mariko’s work. The first book we did together was all about that. It’s about being totally explosive but contained at the same time. I don’t know, Mariko must have really felt that as a kid and that must have been a really powerful emotion because both characters have that. Rose has so much to say and express, yet no way to do it. I think that both of the books are really about tension. I think that is in her work and I pick up on it because we’re both Japanese-Canadians, we’re totally repressed in ways that we don’t talk about. Like our emotions are: everything’s fine.

In other words, you wear Eileen Fisher.

Yes, my Eileen Fisher armor. And I’m not very expressive about what’s bothering me so I think that that does really translate.

Now I have to ask a super personal question: A) really how repressed is your emotional repression? B) do you think this writing, though its not about yourself or a memoir, is this your psychiatry?

I think I’m sort of less uptight in a certain way—and I don’t know if that is from doing the books or because I am getting older. I don’t worry the world is going to crumble if they see me as a weak person.

Read the rest of our interview with Jillian Tamaki in next week’s installment, where we discuss Japanese Canadian internment, politics and “the graphic novel on the hill.”

Read other interviews in Anne Ishii’s series Cartoonists Talk: