On the centenntial of its founding, a short history of the Ghadr Party, and the ghosts that live on

October 25, 2013

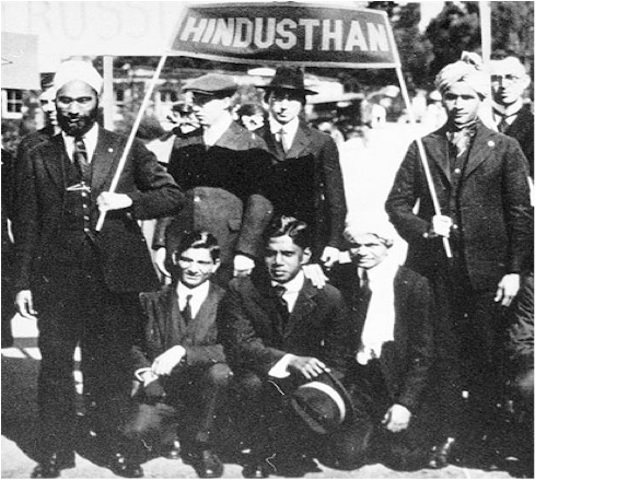

This is the first in a series of pieces related to the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Ghadr Party, an anticolonial, anti-imperialist movement led by South Asian immigrants in the US and Canada in the early 20th century who called for the end of British rule in India while advocating for the rights of immigrants and the working class globally. Read the others: four poetic responses to the literature of the Ghadar movement and a look at its legacy today.

* * *

When journalist Sarangadhar Das showed up on the University of California, Berkeley campus in 1911, he arrived with a mission. By interviewing Indian students who had emigrated to the Bay Area, he sought to end the debate occurring in the Calcutta-based magazine Modern Review: should Indians move to the US? Lala Har Dayal, a philosopher and frequent Modern Review contributor, had, perhaps, sparked the debate: The debate was likely sparked by Lala Har Dayal, a young anarchist who wrote in the magazine that the US is “perhaps the only country in this world which a solitary wandering Hindu* can send a message of hope and encouragement to his countrymen.” Other Indians working along the US West Coast replied with grim stories about labor conditions, racism, and the loneliness of migrant work. The most extreme of these events had occurred in in 1907, in Bellingham, Washington, where white laborers had rioted, beating and chasing Sikh workers out of their homes.

Das’s report, however, confirmed Har Dayal’s proclamation—although with significant caveat that education should be the primary reason for the trans-Pacific journey, not work. (That his Anglophone readership in Delhi and Calcutta was considering moving to the US to work in fields was unlikely, in any event.) In his interviews, Berkeley undergraduates express excitement at having escaped the colonial pull of Oxford and Cambridge, and talk about their ability to discuss science, engineering, and philosophy with each other (if not their fellow students).

One of the students Das interviewed, a young Dhan Gopal Mukerji, had recently arrived from Calcutta by way of Tokyo, and although he was enjoying his classes, he worried about making ends meet. He was working a series of odd jobs (including migrant farm work) when he wasn’t taking courses. Mukerji told Das that he had been enjoying the company of an unnamed Indian socialist and anticolonial leader on campus, but worried that his sway among Indian students might be too strong.

That unnamed leader must have been Lala Har Dayal, who had arrived at Berkeley after a long itinerary (Delhi, London, Paris, Martinique, Algiers, Honolulu, Boston, among others). Har Dayal was ostensibly employed as a lecturer in Eastern philosophy, but he spent most of his time in the Bay Area organizing Indian laborers and students to advocate for better living conditions in the US and to fight against British rule in India. Although Mukerji would ultimately keep his distance from Har Dayal, other students were drawn to him. Bolstered by student support, and dismayed by politics abroad, Har Dayal began building an underground organization and a press; in 1912, Ghadr and its newspaper, Hindust an Ghadr, were launched.

Proper, armed mutiny itself was one of many priorities for Har Dayal, whose advocacy included equal rights for women, Dalit literacy and literary production, free love, and radical pedagogy. By all reports, the leader was an ascetic and philosopher first, whose revolutions—he used the word jihad—had more to do with self-cultivation and mutual communal care in the face of multiple oppressions. He saw colonialism, racism, and sexism as intertwined; he advocated that they be defeated as related, not discrete, causes.

Har Dayal wrote best when he wrote for mutiny. His writings were so forceful that they swayed white Americans to support Indian independence, leading the British Consul in Washington, D.C. to write to their fellow bureaucrats in Delhi that “the trend of American opinion seems to be against admitting the Indian or any other Asiatic, however respectable, because the States don’t want a coloured influx, but in favour of glorifying any individual badmash [asshole], whatever his race, who stands for Liberty and Progress.”

One young engineering student, Kartar Singh Sarabha, was especially moved. He arrived a year after Das’s article was published, but he might have had the most rousing answer for the article. In 1914, when Har Dayal advocated Indians return to India in order to recreate the 1857 Indian War of Independence, Kartar Singh Sarabha was the avant-garde. (Har Dayal, meanwhile, was deported from the US and moved to Berlin.) With other laborers, he returned to Lahore only to find the British Raj had discovered the plot. He was hanged, at the age of 19.

For the most part, the history of the Ghadr Party ends here, even though it managed to regroup after a series of political failures—the failed mutiny of 1914, a series of deportations through 1917, and lack of funds after World War I—and lasted, in smaller forms, through the 1930s.

But its ghosts lived on. Or, perhaps, what lived on were ghadr di gunj—echoes of mutiny, which Har Dayal had claimed, humbly, to have merely channeled from 1857, when the Sepoy Mutiny, a war of Independence, took place. Look, for example, at who claims to have written the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA) Manifesto, in 1928. Underneath “inqilab zindabad – long live revolution!” there is a strangely familiar name: Kartar Singh, President. Or look how, in Dhan Gopal Mukerji’s 1923 bestselling memoir, an unnamed charismatic anarchist leader convinces a young Mukerji that “a Hindu, who wants to find a complete antithesis to his race and culture, had better avoid Europe and come straight to America.” Or look how, in 1931, a mysterious pamphlet, written in Punjabi, begins to circulate with a long-lost Har Dayal essay, barbary de arth (“The Meaning of Equality”) “penned in honor” of HSRA leader Bhagat Singh, who had just been hanged. Even if mutiny is easy to quash, its afterlives are considerably less so.

There are, of course, obvious routes to track these ghadr di gunj. Ajit Singh, Har Dayal’s colleague in California, had sent the leader’s letters to his brother in Lahore. His brother had given them to his son. In 1924, his son wrote a prize-winning essay in the Punjabi magazine Kirti, “On Shaheed Kartar Singh Sarabha.” Four years later, Ajit Singh’s nephew would require a pseudonym for his manifesto. In 1931, Ajit Singh’s nephew, Bhagat Singh, was hanged. He was 23.

Ghadr was easily disparaged and forgotten because it was invested, first and foremost, in youth. (Har Dayal once wrote that “old men and women are, as a rule… living fossils fit only for a museum.”) Because of this, Ghadr was invested in a politics considerably different from older, more moderate projects which held Indian independence as their only goal. Ghadr and its afterlives have wanted, demanded, and strived for something younger, newer, and more.

In short, the continued political (and ethical and aesthetic) concerns of Ghadr have had less to do with the original Party’s short-lived agitation and more to do with the global imagination it sparked: in its subsequent afterlives, it inspired young men and women to demand a different world. This world—“chaotic… with brotherhood and cosmopolitanism,” by Bhagat Singh’s account—was a world without oppression, a world different from the present, and a world (still) worth fighting for.

* (Despite the predominance of Muslim and Sikh laborers along the US West Coast, US publications insisted on calling all Indian immigrants “Hindus”; Indian-American writers unfortunately picked up on this trend. ?

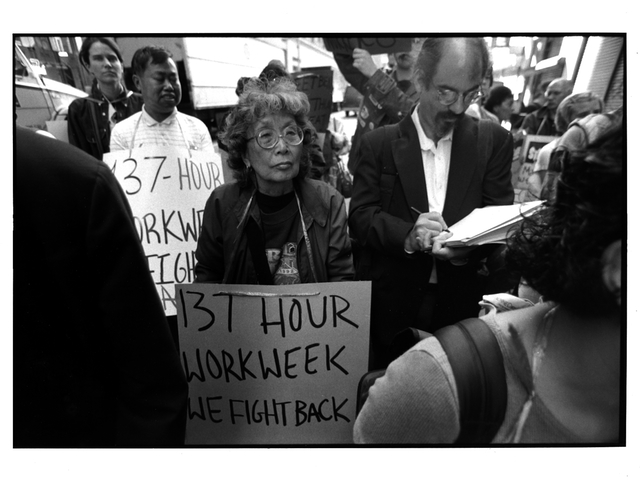

Published in collaboration with the South Asia Solidarity Initiative, which hosted Echoes of Ghadar, a convergence of activists, organizers, and artists from across South Asia in conversation with activists from the United States, inspired by the legacy of the Ghadar Party, in late October.